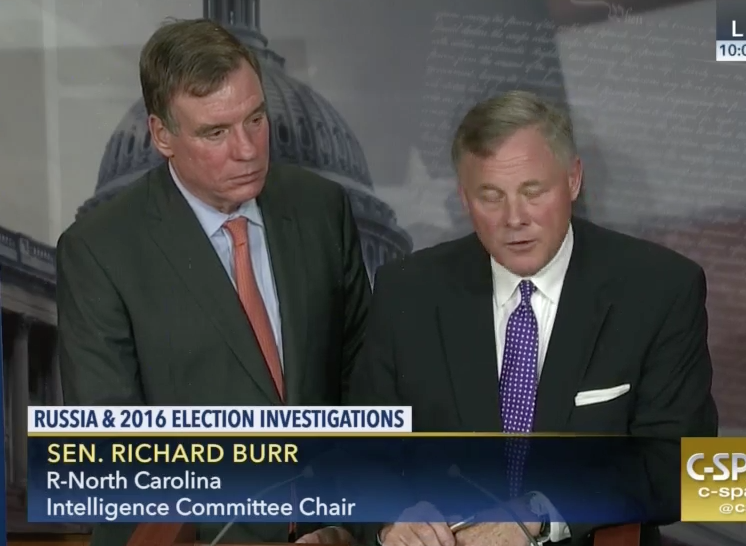

The Senate Intelligence Committee released a 6-page report, titled “Russian Targeting of Election Infrastructure During the 2016 Election: Summary of Initial Findings and Recommendations,” on how to secure elections last night.

While it is carefully hedged (noting that states may have missed forensic evidence and new evidence may become available), it confirms that “cyber actors affiliated with the Russian Government” conducted the operation and that no “vote tallies were manipulated or [] voter registration information was deleted or modified.” It says the intrusions were “part of a larger campaign to prepare to undermine confidence in the voting process,” but in its admission that, “the Committee does not know whether the Russian government-affiliated actors intended to exploit vulnerabilities during the 2016 elections and decided against taking action,” doesn’t explain that the reason Russia would have decided against action was because Trump won.

The report is laudable for the care with which it describes the various levels of intrusion: scan, malicious access attempts, and successful access attempts. As it concludes, in a small number of states (which must be six or fewer), hackers could have changed registration data, but could not have changed vote totals.

In a small number of states, Russian-affiliated cyber actors were able to gain access to restricted elements of election infrastructure. In a small number of states, these cyber actors were in a position to, at a minimum, alter or delete voter registration data; however, they did not appear to be in a position to manipulate individual votes or aggregate vote totals.

Among its recommendations, the report suggests that,

Election experts, security officials, cybersecurity experts, and the media should develop a common set of precise and well-defined election security terms to improve communication.

This would avoid shitty NBC reporting that falsely leads voters to believe over 20 states were successfully hacked.

Ultimately, though, this report offers weak suggestions, using the word “should” 18 times, never once calling on Congress to fulfill some of its recommendations (such as providing resources to states), and simply suggesting that the Executive warn of consequences for further attacks.

U.S. Government should clearly communicate to adversaries that an attack on our election infrastructure is a hostile act, and we will respond accordingly.

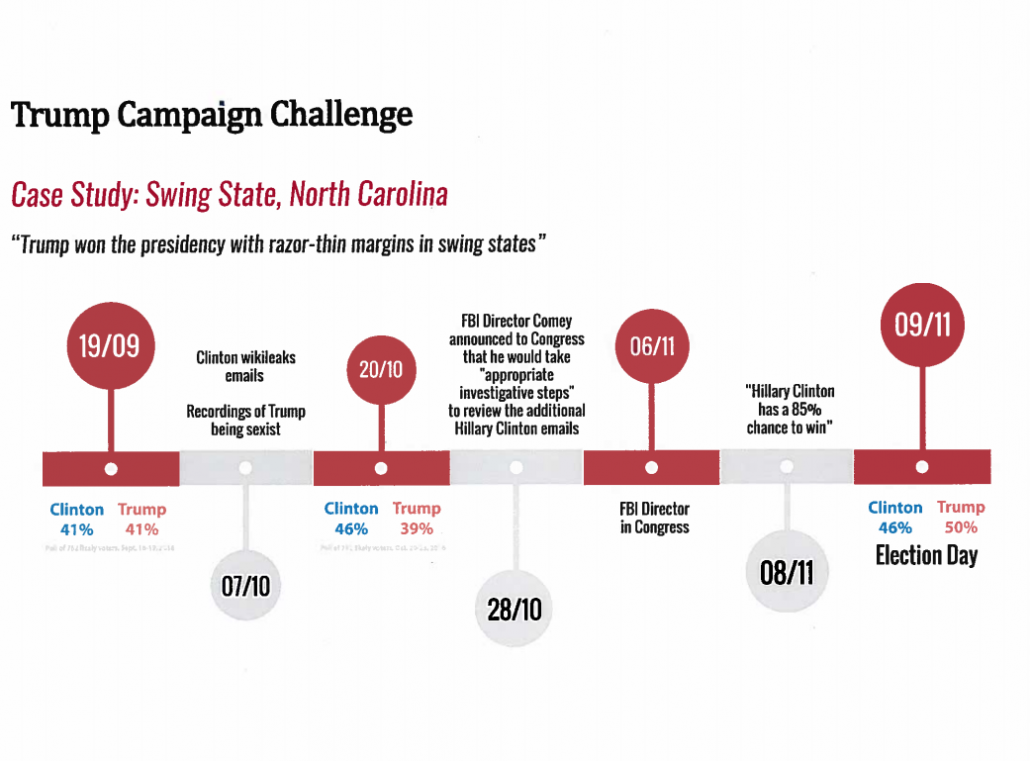

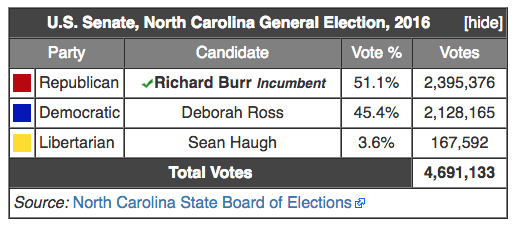

Predictably (especially coming from a Chair whose own reelection in 2016 is due, in part, to his party’s abuse of North Carolina’s administration of elections, the report affirms the importance of states remaining in charge.

States should remain firmly in the lead on running elections, and the Federal government should ensure they receive the necessary resources and information.

I guess Richard Burr would like the Federal government to give his colleagues more money to disenfranchise brown people.

But it’s not just in its weak suggestions that the report falls short. There are two significant silences that discredit the report as a whole: Mitch McConnell, and vendors.

For example, in a long section discussing laying out why DHS’ warnings in 2016 were insufficient, the report complains that the October 7, 2016 statement was not adequate warning.

DHS’s notifications in the summer of 2016 and the public statement by DHS and the ODNI in October 2016 were not sufficient warning.

The report remains utterly silent about Mitch McConnell’s refusal to back a more forceful statement (and, as I’ve noted, Burr and fellow Trump advisor Devin Nunes himself never joined any statement about the attacks).

In other words, while this report talks about gaps and is happy to blame DHS, it doesn’t consider the past and proposed role of top members of Congress.

The other big gap in this report has to do with the vendors on which our election system relies. To be sure, the report does, twice, acknowledge the importance of private sector companies in counting our vote, first when it describes that the vendors would are enticing targets that might need to be bound by more than voluntary guidelines.

Vendors of election software and equipment play a critical role in the U.S. election system, and the Committee continues to be concerned that vendors represent an enticing target or malicious cyber actors. State local, territorial, tribal, and federal government authorities have very little insight into the cyber security practices of many of these vendors, and while the Election Assistance Commission issues guidelines for Security, abiding by those guidelines is currently voluntary.

As a solution, it said that state and local officials should perform risk assessments for election infrastructure vendors, not that they should do so themselves (or be held to any mandated standards).

Perform risk assessments for any current or potential third-party vendors to ensure they are meeting the necessary cyber security standards in protecting their election systems.

Not all states and almost no local officials are going to have the ability to do this risk assessment, and there’s no reason why it should be done over and over again across the country.

That’s particularly true given the fact that (as the report addresses the vulnerability posed by, but provides no remedy) the election vendor market has gotten increasingly concentrated.

Voting systems across the United States are outdated, and many do not have a paper record of votes as a backup counting system that can be reliably audited, should there be allegations of machine manipulation. In addition, the number of vendors selling machines is shrinking, raising concerns about supply chain vulnerability.

The report also suggests that DHS educate vendors.

DHS should work with vendors to educate them about the potential vulnerabilities of both voting machines and the supply chains.

But in a report that acknowledges the key role played by vendors in administering our elections, the report remains silent about Russian efforts to compromise them in 2016. Indeed, in its accounting of how many states were affected, the report admits its numbers don’t include vendors.

In addition, the numbers do not include any potential attacks on third-party vendors.

And yet — thanks in large part to Reality Winner — we know Russia did target vendors. Not only did they target them, but they appear to have succeeded, and succeeded in a way that may have affected the vote in North Carolina, Burr’s state.

In short, the report leaves a key aspect of known Russian efforts to target the vote completely unexamined, and it doesn’t consider the many ways that by compromising vendors in ways beyond cyberattacks might affect the vote.

Perhaps the report is silent about vendors precisely because of Winner’s pending case, to avoid publicly mentioning in unclassified form the attacks that the document she is accused of leaking. Or perhaps the committee just did an inadequate job of reviewing what happened in 2016.

Whichever it is, it’s unacceptable.