In Reality Winner Case, Government Warns of Recruitment by Media Outlets that “Procure the Unauthorized Disclosure of Classified Info”

As I’ve reported recently Reality Winner has claimed both that her interview with the FBI was not consensual and that she should be released on bail like people who’ve leaked more sensitive documents, including David Petraeus. Significantly, Winner made claims about her interview and DOJ’s lack of related accusations to suggest the leak of the single document to the Intercept is all they’ve got on her.

The government responded to Winner’s claims — in their response to her request for bail — with a whole new set of claims not included in other documents (on top of making fairly ridiculous claims to suggest Winner should be detained when those who had access — and in the case of David Petraeus, leaked — far more classified information were not).

In the response itself, they raise issues that are fair and significant. But they all seem designed to suggest that Winner must be treated more harshly than Petraeus because she’s more likely to be “recruited” by “non-governmental organizations and media outlets that advocate and procure the unauthorized disclosure of classified information.”

At the same time, the Defendant is an attractive candidate for recruitment by well-funded foreign intelligence services and non-governmental organizations and media outlets that advocate and procure the unauthorized disclosure of classified information.

Consider how the government treats different media outlets.

The Washington Post

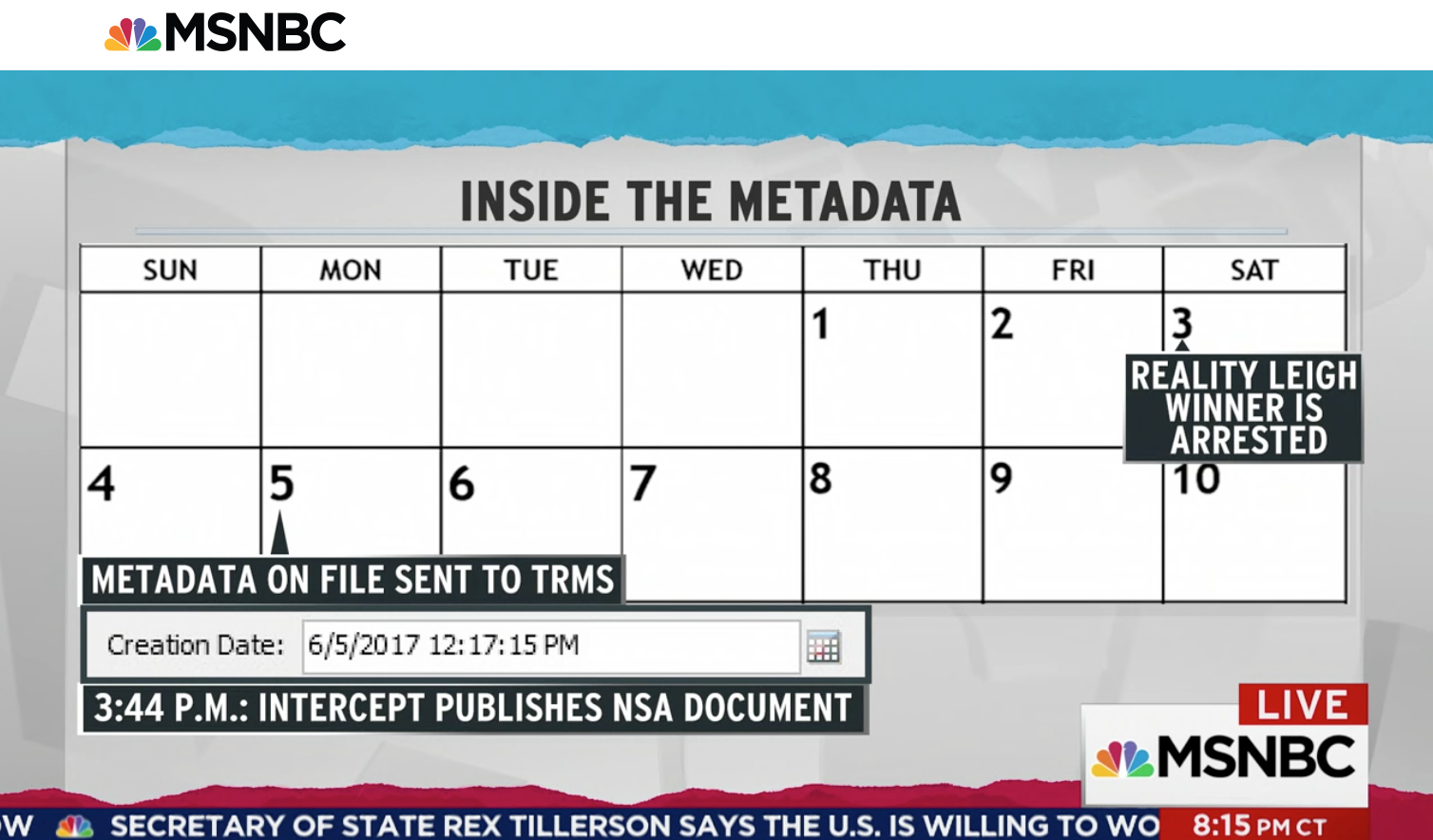

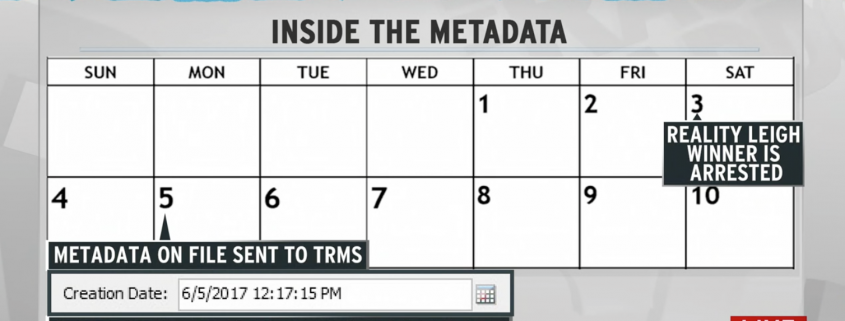

First, the government’s description of Winner’s phone searches suggest Winner sent the document to a “print news outlet” in addition to the Intercept, and kept looking at both to see if they published the document.

- On May 9, the Defendant searched for the secure mailing address of a Print News Outlet, viewed a document called “How to Share Documents and News Tips with [Print News Outlet] Journalists” on the Print News Outlet’s website, searched for an Online News Outlet and “secure drop,” and viewed the Online News Outlet’s page containing instructions for the anonymous transmission of leaked information.

- On May 12, a few days after she mailed the leaked document, the Defendant searched online for the Print News Outlet referenced on May 9, as well as the Online News Outlet to which she transmitted the leaked document, and viewed the homepages of both publications.

- On May 13, the Defendant searched for the Print News Outlet, viewed its homepage, and then searched “[IC component] leak” and “[IC component] leak [Foreign Country]” on multiple occasions.

- On May 14, the Defendant searched for and viewed the Print News Outlet’s homepage, and then searched within the Print News Outlet’s website for the name of the relevant IC component. She also searched for and viewed the Online News Outlet’s homepage.

- On May 22, the Defendant viewed both the Print News and Online News Outlets’ websites, and she searched for the name of the relevant IC component within both websites.

The Washington Post’s “confidential tips” page comes up on a search for “How to Share Documents and News Tips” (though the page does not now have that name). That suggests Winner shared a copy of this document with the WaPo as well as the Intercept. But the focus in these materials on a completed crime is exclusively focused on the Intercept (which also is not named).

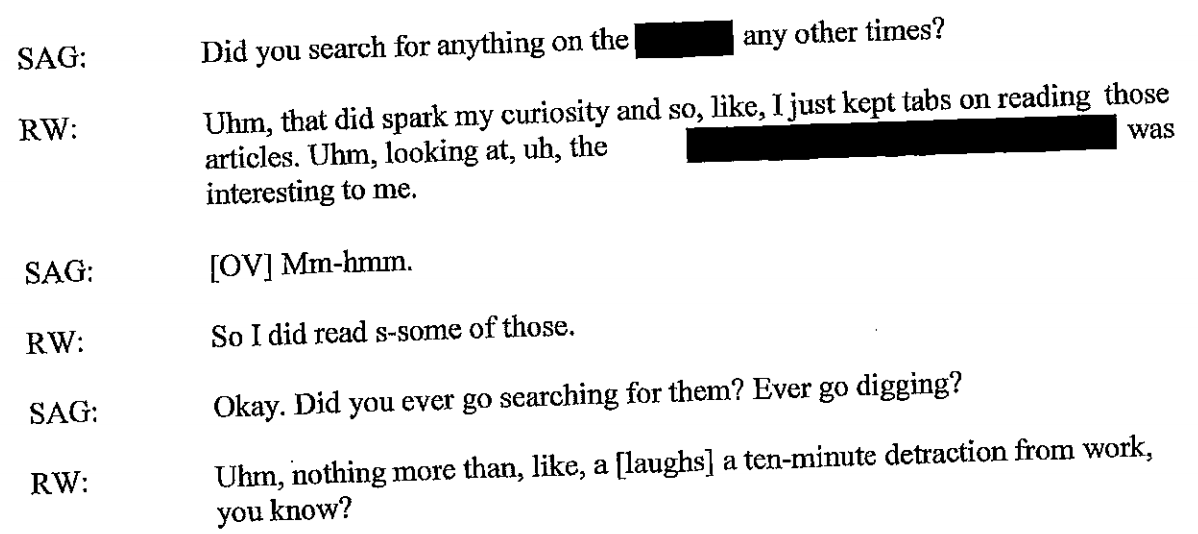

The interview transcript released with this filing does not, apparently, discuss Winner’s leak to what appears to be the WaPo, aside from asking if she sent the leaked document anywhere else, to which she said “no.” The agents interviewing her tipped her that the document had been sent to an online news source that she “subscribes” to. So FBI may not have mentioned WaPo because WaPo did nothing with the story — or at least nothing with a source who then informed the government, which is how the Intercept got exposed — meaning the FBI did not yet know about it. Or perhaps the FBI was just far more interested in the fact that Winner leaked to the Intercept.

Wikileaks and Anonymous

The filing does its most significant damage in repeating Winner’s support for WikiLeaks, Edward Snowden, and Anonymous. According to the filing, at the same time she was looking for clearance jobs in November 2016 (at the end of her deployment), she was researching anonymous and Wikileaks.

The Defendant’s duplicity is starkly illustrated by the fact that she researched opportunities to access classified information (multiple searches for jobs requiring a security clearance on ClearanceJobs.com) at the same time in November 2016 that she searched for information about anti-secrecy organizations (Anonymous and Wikileaks).

And in March, she told her sister she was “on Assange’s [and Snowden’s] side.”

On March 7, 2017, the Defendant searched for online information about Vault 7, Wikileaks’s alleged compromise of classified government information. Later on March 7, 2017, the Defendant engaged in the following Facebook chat with her sister in which she expressed her delight at the impact of the alleged compromise reported by Wikileaks:

SISTER: OMG that Vault 7 stuff is scary too

WINNER: It’s so awesome though. They just crippled the program.

SISTER: So you’re on Assange’s side

WINNER: Yes. And Snowden

It’s not just that Winner is reading Wikileaks and Snowden-leaked documents (which the government would be happy to use to villainize a leaker in any case). She’s cheering the destruction of CIA (and by association, NSA) capabilities. Which is not something the more prolific leaker David Petraeus did.

The curious declassification of an FBI interview about leaking

Before I get into how these materials treat the Intercept, let me take a detour to talk about the declassification of Winner’s interview which, because it discusses her work at NSA, includes a lot of information that must be classified.

As a number of outlets noted (I believe Politico reported it first), when the transcript of her FBI interview was first released, it included Winner’s social security number and date of birth — a no-no for PACER documents. It included her home computer password. It also revealed Winner worked on collection targeting Iranian Aerospace Forces Group, a remarkable disclosure given that the government says Winner can’t be released because she’ll be targeted by foreign governments (in addition to “non-governmental organizations and media outlets that advocate and procure the unauthorized disclosure of classified information”); they’ve just put a bullseye on her back for Iran. It also reveals she used to work for a drone mission. It includes the code name and the street name of her NSA location.

For either privacy and security reasons, those are remarkable disclosures.

Now consider what they did redact.

There’s a reference to Russian hacking (or the election), and Winner’s description of something akin to that. There’s a few more references, perhaps on the election, again redacted.

Perhaps the most interesting (and understandable) redaction is her explanation for why she thought the collection points on Russian hackers were already compromised.

[sigh] I had figured that, uhm, [half line redacted] that it didn’t matter anyway. Uhm honestly, uh, I just figured that whatever we were using had already been compromised, and this report was just going to be like a – one drop in the bucket.

All of which is to say the classification decisions here are pretty random.

Which is all the more interesting given the fact that the document has no declassification notes, describing who declassified it and for what purpose. If I’m Winner’s lawyers, I’m on the phone with former ISOO head Bill Leonard (who has served as an expert witness in past leak cases), asking him to testify that in a case about mishandling classified information, the government didn’t handle this document in rigorous fashion.

The Intercept: hiding the name, the motive, and a few more details

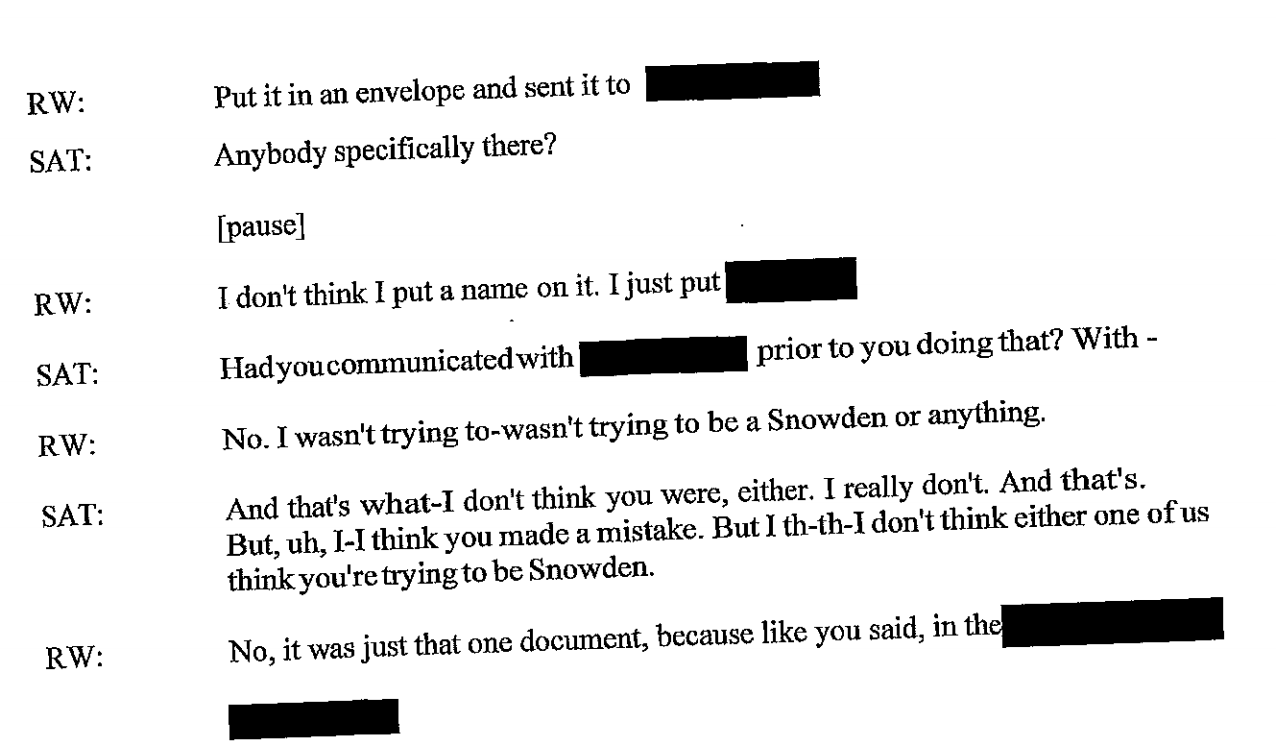

Which brings me to the decisions about redactions on parts of the transcript that pertain to the Intercept.

It hides the Intercept’s name, but also several references to her motive, including one very long description (on PDF 69)

More interesting, it redacts details about how she mailed it to the Intercept.

And redacts another passage where she describes how she found the address to send it to the Intercept — the actual details of which are included in the passage on her phone searches, above.

It redacts another passage asking whether she included anything in the envelope to the Intercept.

All of which is to say that in submissions that claim Winner is a particular risk because she might be “recruited” by NGOs and “media outlets that advocate and procure the unauthorized disclosure of classified information,” it is still hiding key details about Winner’s descriptions of her actions with respect to the Intercept.

After reading this transcript, I’m actually surprised the government hasn’t (yet) taken a harsher approach, perhaps charging her for a leak to the WaPo or for lying, initially, to the FBI (not charging her for lying to the FBI is one way, I guess, where she is getting the treatment David Petraeus got).

That may suggest they’re entertaining going after the Intercept here, for “recruiting” Reality Winner — a replay of the tactic they tried with Chelsea Manning years ago, only this time with an Attorney General and a Congress rushing to invent new categories of non-state hostile intelligence services to criminalize some kinds of publishing.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)