Why Has the Intelligence Community Missed So Many Digital Bales of Hay?

In a piece on the intelligence community’s increasing reliance on SIGINT, LAT reports that the amount of the President’s daily brief that comes from SIGINT has increased from 60% since 2000.

Determined to identify and track Al Qaeda terrorists and to prevent another attack after Sept. 11, 2001, the NSA set about vastly enlarging its ability to capture, store and exploit the ocean of texts, emails, videos and other electronic communications.

“They took on a new mission that required sifting vast amounts of data to find a few important signals,” said Stewart Baker, who was the NSA’s general counsel from 1992 to 1994 and held top Homeland Security Department jobs in the George W. Bush administration.

Today the NSA secretly siphons an almost unimaginable number of foreign government, corporate and private communications from the World Wide Web, according to the trove of classified material disclosed by Edward Snowden, the fugitive former NSA contractor. One document leaked last week revealed that NSA computers take in 500 million “communications connections” per month in Germany alone.

[snip]

About 60% of the president’s daily brief, the highly classified intelligence summary delivered to the White House each morning, was based as of 2000 on “signals intelligence,” or intercepted communications, according to a declassified NSA document from December of that year. The NSA portion has increased since then, former officials say.

“Over the last 10 years, because of the Internet gold mine, signals intelligence has become the primary vehicle for U.S. intelligence collection,” said James Lewis, director of the technology and public policy program at the nonpartisan Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

WaPo’s original story on PRISM (which, remember, is just a computer interface making it easier for analysts to access data from just 9 companies) reported that 1 in 7 pieces of intelligence in the PDB derived from PRISM, or a total of 1,477 pieces of intelligence last year (10,339 pieces of intelligence in all the PDBs last year, then?).

An internal presentation of 41 briefing slides on PRISM, dated April 2013 and intended for senior analysts in the NSA’s Signals Intelligence Directorate, described the new tool as the most prolific contributor to the President’s Daily Brief, which cited PRISM data in 1,477 items last year. According to the slides and other supporting materials obtained by The Post, “NSA reporting increasingly relies on PRISM” as its leading source of raw material, accounting for nearly 1 in 7 intelligence reports.

Remember, this is all non-public information.

Back in 2011, however, the intelligence committee failed to understand the Arab Spring that was breaking out in public fora for all the world to see (I once quipped that those who followed Democracy Now’s Sharif Kouddous on Twitter had a better understanding of what was going on than the CIA).

And as recently as this year’s confirmation hearing for John Brennan, he admitted that the CIA needed to better monitor public social networks.

BRENNAN: Well clearly, counterterrorism is going to be a priority area for the intelligence community and for CIA for many years to come. Just like weapons proliferation is as well. Those are enduring challenges. And since 9/11 the CIA has dedicated a lot of effort, and very successfully, they’ve done a tremendous job to mitigate that terrorist threat.

At the same time, though, they do have this responsibility on global coverage. And so, what I need to take a look at is whether or not there has been too much of an emphasis of the CT front. As good as it is, we have to make sure we’re not going to be surprised on the strategic front and some of these other areas, to make sure we’re dedicating the collection capabilities, the operations officers, the all-source analysts, social media, as you said, the — the so-called Arab Spring that swept through the Middle East. It didn’t lend itself to traditional types of — of intelligence collection.

There were things that were happening — happening in a — on a populist — in a populist way, that, you know, having somebody, you know, well positioned somewhere who can provide us information is not going to give us that insight, social media, other types of things. So I want to see if we can expand beyond the sodestra (ph) collection capabilities that have served us very well, and see what else we need to do in order to take into account the changing nature of the global environment right now, the changing nature of the communication systems that exist worldwide.

Though Brennan suggested that a focus on leaders rather than common people led to CIA’s blindness in this case (I’d add, a reliance on brokers like Egypt’s Omar Suleiman or Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Nayef, who have an interest in depicting unrest in their countries as threats to friendly governments, distorts reality).

But whether the NSA or the CIA should have seen the revolts bubbling up in plain sight, both missed it because of all the secret stuff they remained focused on.

I’m not actually advocating for the CIA to start trolling Twitter more aggressively. Still, if the focus on secret stuff has led to blindness, we need to rethink our obsession with secret digital haystacks.

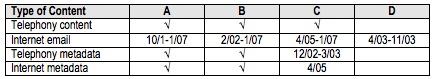

![[NSA presentation, PRISM collection dates, via Washington Post]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/WaPo_Prism-Slide5_06JUN2013_300pxw.jpg)

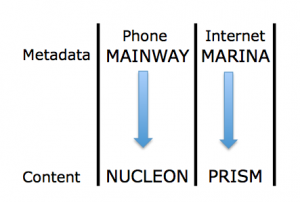

![[graphic: Electronic Frontier Foundation via Flickr]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/NSA-ATT-Spying_EFF-Flickr.jpg)

![[photo: DeveloperTutorials.com]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/DataCenter_GOOG-DallesOR_DeveloperTutorials_11MAR2010_300pxw.jpg)

![[photo: DataCenterKnowledge.com]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/DataCenter_APPL-MaidenNC_DataCenterKnowledge_29APR2013_300pxw.jpg)

![[photo: DataCenterKnowledge.com]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/DataCenter_MSFT-DublinIreland_DataCenterKnowledge_17MAR2011_300pxw.jpg)