Freedom And Equality: Freedom From Domination Part 2

Introduction and Index To Posts In This Series

Honor

I began this series with a discussion of Freedom With Honor: A Republican Ideal by Philip Pettit, 64 Social Research, Vol. 1, P. 52. I want to emphasize the nature and importance of honor in this paper. Pettit says that decent societies

… do not deprive a person of honor. Specifically, they do not undermine or jeopardize a person’s reasons for self-respect. More specifically still, they do not signal the rejection of the person from the human commonwealth: they do not cast the person as less than fully adult or human.

… To be deprived of honor is to be cut out of conversation with your fellows. It is to be denied a voice or to be refused an ear: it is not to be allowed to talk or not to be treated as ever worth hearing. People differ, topic by topic, in how far they are thought worth listening to; they enjoy lower and higher grades of esteem. But to be deprived of honor is to be denied the possibility of ever figuring in the esteem stakes; it is to be refused the chance to play in the esteem-seking game.

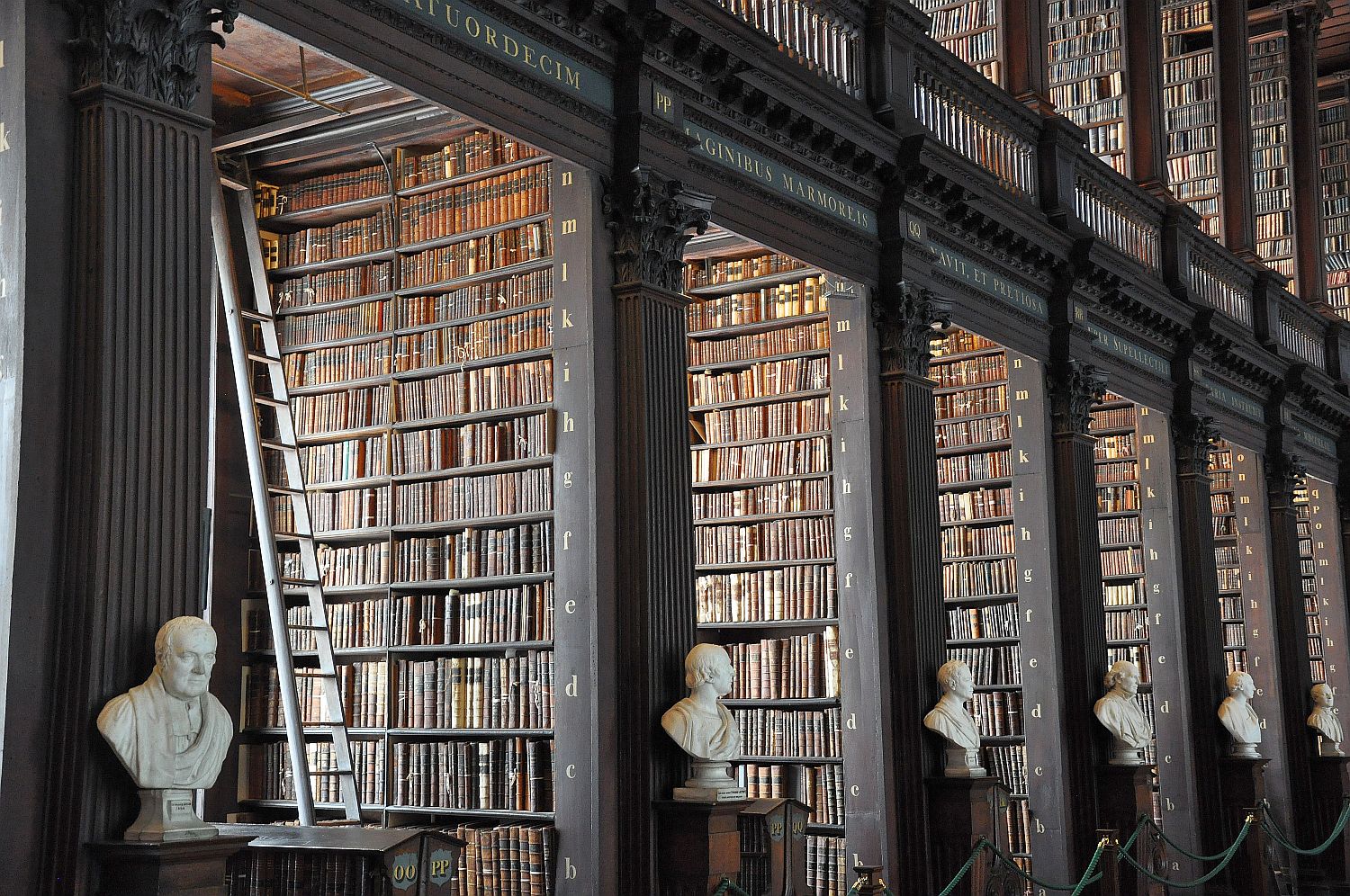

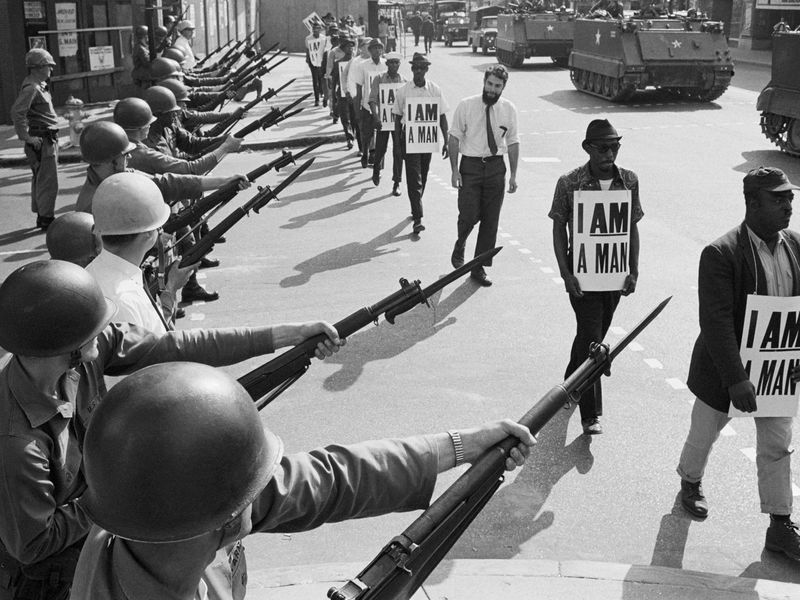

Honor in this sense is perhaps the most important human need after our material needs are met. Pettit does not offer examples at first (his examples are discussed below), so I offer this one. Martin Luther King was instrumental in the strike of the Memphis sanitation workers; he was murdered while working on it. Here’s a Smithsonian article on the strike, which features this thrilling image.

I Am A Man

David Remnick of the New Yorker recently worte: “W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that Andrew Johnson’s unwillingness to enact policies to give freedmen land, a decent education, or voting rights resided, first and foremost, in “his inability to picture Negroes as men.”” I don’t know if Dr. King and the other organizers were consciously thinking of this quote, and I don’t know exactly what they meant by the words on the signs. But to me, the men in this picture demand recognition as a human beings. These men were willing to die rather than endure second class status. They insisted on being recognized as equal participants in society. Fair wages were an issue, but that’s not what the signs demand. They are not inferiors begging for fair treatment, or dependants asking for a higher allowance. They are each on of the Men in All Men Are Created Equal. They demand what Pettit would call honor.

Once you notice the demand for this kind of honor, you see it everywhere. This is from an op-ed by Moira Donegan in The Guardian on Jeffrey Epstein:

He was protected by the broad cultural antipathy toward treating sexual abuse as real harm, the often hostile reaction to the premise that teenage girls should matter as much as adult men.

This is from a piece on being a good customer at a restaurant, also in the Guardian:

There are strategies galore for dealing with rudeness, which mostly end with a waiter spitting in your food, but the main reason you should behave properly as a diner is that you are human and so are they.

Denial of honor in societies based on noninterference

Pettit says a society which prioritizes freedom as non-interference can permit institutional humiliation, domination, and denial of honor, even in a constitutional system supposedly based on equality. How? Imagine you are charged with making laws in such a society. You will recognize that all laws are interferences with the freedom of your members. They will have to observe laws, they will be penalized if they violate them.* You will recognize that some forms of interference are unlikely, and others unlikely to cause what you consider serious injury. You will not want to pass laws to limit the freedom of your members unless you are certain that the benefits will outweigh the costs of enforcement.

In that situation, some people will have the ability to interfere with the liberty of others. People will know that those others can interfere with their freedom, even to dominate them. That in turn leads to servility: the effort to avoid domination, and to ingratiate themselves with the dominator. He offers this example:

Think of the way Mary Wollstonecraft deplores the “littlensses” and “sly tricks” and “cunning” to which women are driven, in her view, because of their vulnerability in relation to their husbands.

It is vain to expect virtue from women till they are, in some degree, independent of man; nay, it is vain to expect that strength of natural affection, which would make them good wives and mothers. Whilst they are absolutely dependent of their husbands they will be cunning, mean, and selfish.

Cites omitted.

This “cunning” is dramatized in Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen**.

“Elizabeth Bennet,” said Miss Bingley, when the door was closed on her, “is one of those young ladies who seek to recommend themselves to the other sex by undervaluing their own; and with many men, I dare say, it succeeds. But, in my opinion, it is a paltry device, a very mean art.”

“Undoubtedly,” replied Darcy, to whom this remark was chiefly addressed, “there is a meanness in all the arts which ladies sometimes condescend to employ for captivation. Whatever bears affinity to cunning is despicable.

Notes

1. In current usage, the word honor means formal respect, and we reserve it for special occasions: to honor the victorious US Women’s soccer team; to honor a dead war hero. In our usage, it is something we do woth respect to others, not something we seek or need for ourselves; it’s not as a personal matter. We occasionally use it to describe a goal for individuals: to live honorably. Pettit uses it more like a combination of political and social equality. In our political discourse, the word equality is contested, sadly. I’m going to use the term civic dignity, which is clumsy but at least not contested, and which seems to me to capture the essence of Pettit’s term honor. I will also use the words honor and dignity together to convey the idea.

2. It’s fascinating to read this material in the context of Trump and the Republicans. They flatly reject the premise that all humans are entitled to civic dignity. It reminds us that we have to fight, literally, for honor for all if we want to keep it for ourselves.

====

* Pettit also says that taxes are a violation of negative liberty, and that citizens will be taxed to pay for enforcing all laws. This is true at the state level, but not at the federal level. See, e.g. Beardsley Ruml, Taxes For Revenue Are Obsolete.

** The context of this passage is that without quite saying so, Austen makes us understand that Caroline Bingley wants to attract the affections of Mr. Darcy. This isn’t the first time she has attacked Elizabeth, and it isn’t the last time she uses cunning to reach her goal. It’s passages like this one that make Pride and Prejudice worth multiple readings.