Does Maersk Count as US Critical Infrastructure?

I Back when Sony Pictures got hacked after Sony Everything Else had been hacked serially over the course of 15 years, the US government declared that multinational studio owned by a Japanese parent US critical infrastructure entitled to heightened cybersecurity protection. That’s one of the bases for which the US imposed sanctions on North Korea. The designation also ramped up the ways in which FBI could help Sony.

The listing of a multinational movie studio as critical infrastructure led many people to understand just how broad the definition of CI is in the US, including (in the same Commercial Facilities Sector) a bunch of things that might better be called soft targets.

- Entertainment and Media (e.g., motion picture studios, broadcast media).

- Gaming (e.g., casinos).

- Lodging (e.g., hotels, motels, conference centers).

- Outdoor Events (e.g., theme and amusement parks, fairs, campgrounds, parades).

- Public Assembly (e.g., arenas, stadiums, aquariums, zoos, museums, convention centers).

- Real Estate (e.g., office and apartment buildings, condominiums, mixed use facilities, self-storage).

- Retail (e.g., retail centers and districts, shopping malls).

- Sports Leagues (e.g., professional sports leagues and federations).

That’s when I learned that DHS was on the hook for protecting Yogi Bear Jellystone and KOA campground facilities around the country from cyberattack.

Since 2014, DHS belatedly added one thing to its critical infrastructure designation: elections. Though DHS doesn’t appear to have updated the website to reflect that designation yet (though maybe I’m missing it; I’ll call tomorrow to ask them where it is).

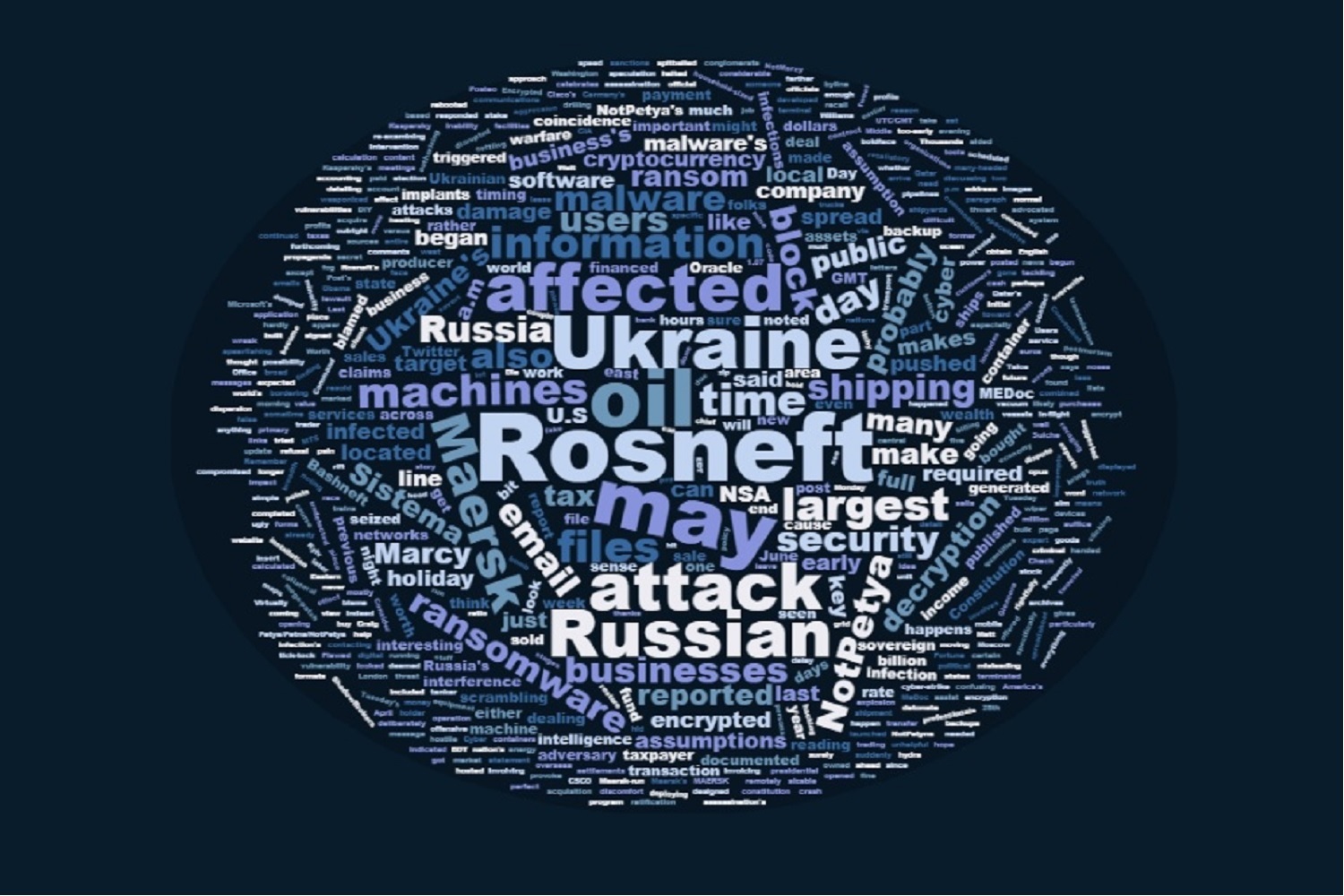

Anyway, the global impact of the NotPetya (which I’ll henceforth call Nyetna, because that’s my favorite name for it) attack, particularly its impact on Danish shipping giant Maersk, has me wondering whether anything Nyetna affected counts as would count as critical infrastructure. The impact on Maersk has had significant effect at several ports in the US.

Danish shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk, one of the global companies hardest hit by the malware, said Thursday that most of its terminals are now operational, though some terminals are “operating slower than usual or with limited functionality.”

Problems have been reported across the shippers’ global business, from Mobile, Alabama, to Mumbai in India. When The Associated Press visited the latter city’s Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust on Thursday, for example, it witnessed several hundred containers piled up at just two yards, out of more than a dozen yards surrounding the port.

“The vessels are coming, the ships are coming, but they are not able to take the container because all the systems are down,” trading and clearing agent Rajeshree Verma told the AP. “The port authorities, they are not able to reply (to) us. The shipping companies they also don’t know what to do. … We are actually in a fix because of all this.”

Probably the most important impact was on Maersk’s terminal in LA.

A cyberattack that infected computers across Europe and then spread into the United States halted operations at the Port of Los Angeles’ largest terminal Tuesday — and raised worries that destructive software could ricochet around the world and disrupt the critical supply chain.

APM Terminals — where Danish shipping carrier A.P. Moller-Maersk operates — turned truckers away all day, as did their terminals in Rotterdam, New York and New Jersey.

So does Maersk, and the 18% of global container shipping business it carries, count as US critical infrastructure?

Given that Maersk, not the several ports affected, is the victim, it’s not clear. Here’s how DHS defines the CI aspect of maritime shipping.

- Maritime Transportation System consists of about 95,000 miles of coastline, 361 ports, more than 25,000 miles of waterways, and intermodal landside connections that allow the various modes of transportation to move people and goods to, from, and on the water.

But if Sony can count as US CI, it seems Maersk (or any comparable shipping giant) should as well.

It may not matter, as the Executive Branch seems to be hiding even further under their bed than they were after the WannaCry attack, with this being the one mention of the hack from the White House.

SECRETARY PERRY: So let’s get over on the grid. Obviously, the Department of Energy has a both scientific, they have a historic reason to be involved with that. One is that, at one of our national labs, we have a test grid of which we are able to go out — one of the reasons that the Department of Homeland Security and DOE is involved with grid security is that DOE operates a substantial grid — a test grid, if you will — where we can go out and actually break things. We can infest it with different viruses and what have you to be able to analyze how we’re going to harden our grid so that Americans can know that our country is doing everything that it can to protect, defend this country against either cyberattacks that would affect our electrical security or otherwise.

So the ability for us to be able to continue to lead the world — I think we all know the challenges. We saw the reports as late as today of what’s going on in Ukraine. And so protecting this country, its grid against not just cyber, but also against physical attacks, against attacks that may come from Mother Nature, weather-related events — all of that is a very important part of what DOE, DHS is doing together.

DHS is preoccupied rolling out Muslim Ban 3.0 and other flight restrictions.

By all appearances, Nyetna primarily targeted Ukraine. But in hitting Ukraine, it significantly disabled one of the key cogs to the global economy, the world’s biggest container shipping company. Does that count as an attack on the US, or at least its critical infrastructure?

Update: I’ve confirmed that “shipping lines” are included in Maritime Transportation. So Maersk would seem to count as critical infrastructure.