That Peter Strzok 302 Probably Comes from the Obstruction Case File

I’d like to provide a plausible explanation for questions about an FBI 302 released yesterday as part of the Mike Flynn sentencing.

As a reminder, after Flynn pled guilty, his case ultimately got assigned to Emmet Sullivan, who is laudably insistent on making sure defendants get any possible exonerating evidence, even if they’ve already pled guilty. On his orders, the government would have provided him everything early in 2018.

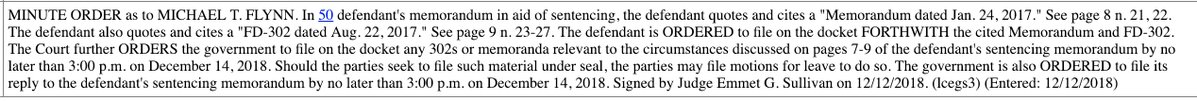

In Flynn’s sentencing memo submitted earlier this week, his lawyers quoted from an Andrew McCabe memo written the day of his interview and a 302 that they described to be dated August 22, 2017, a full 7 months after his interview. In predictable response, Sullivan instructed the government to provide that McCabe memo and the 302 cited by Flynn’s lawyers.

When the government submitted those two documents yesterday, they raised still more questions, because it became clear the 302 (which is what FBI calls their interview reports) in question was of an interview of Strzok conducted on July 19, 2017, drafted on July 20, and finalized on August 22. The 302 described that Strzok was the lead interviewer in Flynn’s interview, whereas his interviewing partner wrote up the 302.

This has raised questions about why we only got the Strzok 302, and not the original one cited by Strzok.

While I don’t have a full explanation, certain things are missing from the discussion.

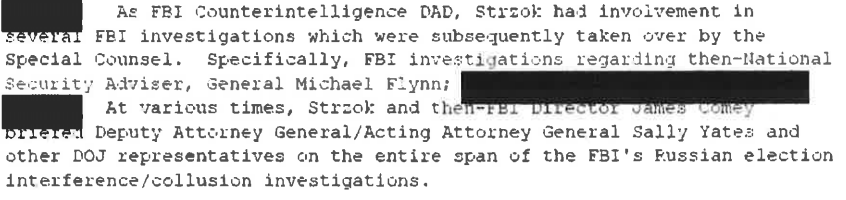

Folks are misunderstanding what the 302 represents. It is not the 302 reporting the Flynn interview. Rather, it is a 302 “collect[ing] certain information regarding Strzok’s involvement in various aspects of what has become the Special Counsel’s investigation,” which he described to one Senior Assistant Special Counsel and an FBI Supervisory Special Agent, presumably one assigned to SCO. The 302 notes that Strzok wasn’t just involved in the investigation of Mike Flynn. While it redacts the names, it also lists the other parts of the investigation he oversaw.

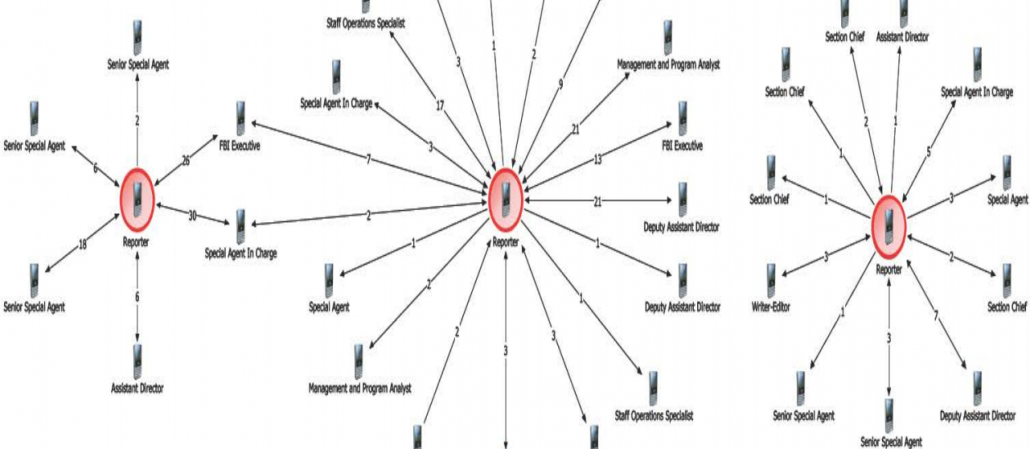

We know he was involved in the Papadopoulos investigation, and it appears likely he was involved in the Page investigation, as well. Both this passage and the next one describes the people at DOJ that Strzok interacted with in these investigations, which is further evidence the purpose of this 302 is not to capture the interview, but instead to capture details about internal workings surrounding the investigation itself.

The part of this 302 that is unredacted makes up maybe a third of the substance of the 302, and it appears between almost full page redactions before and after the part describing the Flynn interview. Again, the other stuff must be as pertinent to the purpose of this 302 as the Flynn interview itself.

I had thought the interview might be an effort by SCO to capture Strzok’s institutional knowledge in the wake of the discovery of his texts with Lisa Page as a way to prepare some other FBI Agent to be able to testify at trial. But the timing appears wrong. DOJ’s IG first informed Mueller about the texts on July 27, and he was removed from the team the next day (though not processed out of that clearance, according to this report, until August 11).

Strzok was assigned to lead the Russia investigation in late July 2016. 197 Page also worked on the Russia investigation, and told us that she served the same liaison function as she did in the Midyear investigation. Both Page and Strzok accepted invitations to work on the Special Counsel staff in 2017. Page told the OIG that she accepted a 45-day temporary duty assignment but returned to work in the Deputy Director’s office at the FBI on or around July 15, 2017. Strzok was removed from the Special Counsel’s investigation on approximately July 28, 2017, and returned to the FBI in another position, after the OIG informed the DAG and Special Counsel of the text messages discussed in this report on July 27, 2017. [my emphasis]

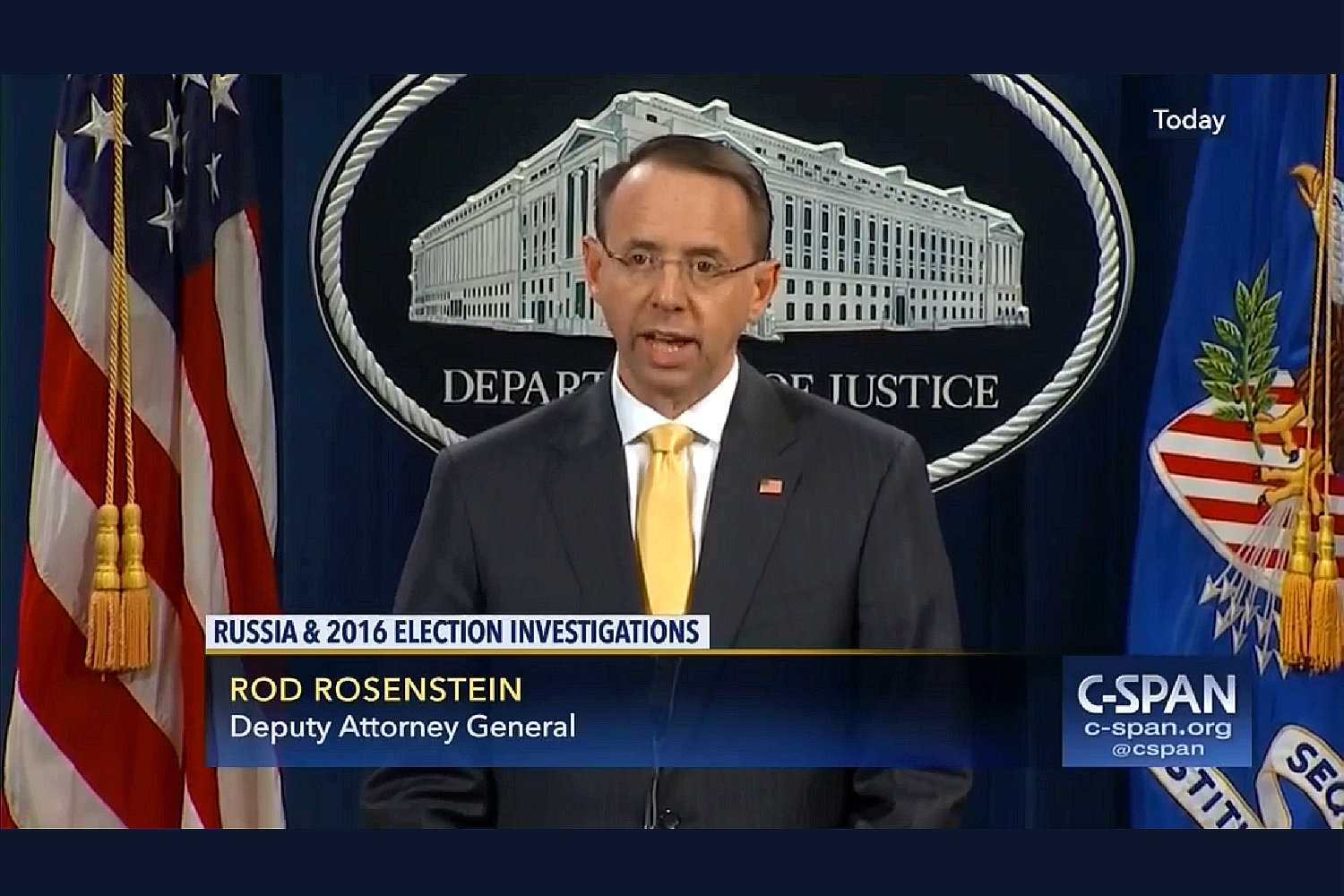

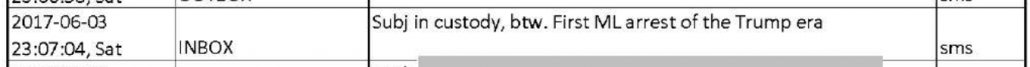

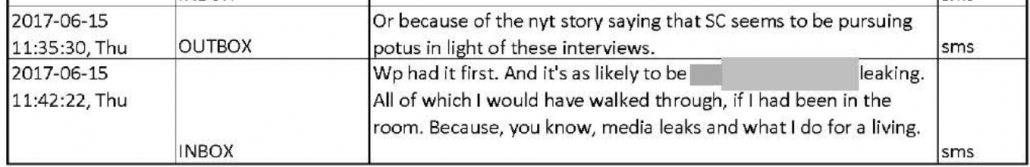

But the interview does line up temporally with other known events: Around the time Strzok was interviewed, both Rod Rosenstein and Sally Yates were interviewed in the obstruction case, interviews that would also result in 302s summarizing the interview. Jim Comey had already turned over his memos on meetings with Trump by that point; eventually he would be interviewed by Mueller as well, though it’s not clear when that interview (and correlating 302) was.

Yates and Comey are both among the people the 302 explicitly describes Strzok interacting with.

In other words, it seems likely that this 302 was designed to capture what Strzok knew about the internal workings of DOJ and FBI surrounding the Mike Flynn interview, and likely was focused on explaining the significance of Flynn’s lies and subsequent firing to the obstruction case. That is, this would have served to turn what Strzok learned as investigator into information Strzok had to offer as a witness, in the same way that Mueller would have had to turn what Comey and Rosenstein knew as supervisors into information relevant to their role as witnesses. It probably had the unintended benefit of capturing what Strzok knew about key parts of the investigation before he was indelibly tainted by the discovery of his text messages.

If this is the explanation, it raises questions about why we only got this 302, and not the original one.

There’s a very likely answer to that: that original 302 presumably didn’t include this detail, at least not in the easily quotable form that would serve Flynn’s political purposes.

Flynn has, as far as we know, gotten everything. His lawyers chose which of those documents to quote. And Judge Sullivan only ordered the government to produce these two (though invited them to submit anything else they wanted to, an invitation they did not take up).

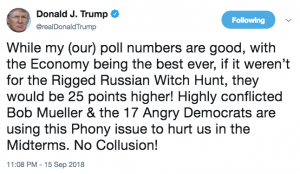

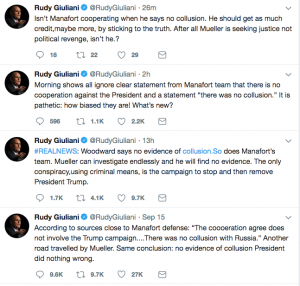

But there’s another piece of evidence that there’s far less to this 302 than some are suggesting: because Republicans in Congress chased down this detail over the last year, and in their most recent incarnation of drumming up conspiracies about Flynn, in questioning Jim Comey just a week ago, Trey Gowdy did not focus on the question of the 302s produced, but instead tried to suggest that Flynn didn’t mean to lie.

Note that, contrary to what right wingers have suggested, Comey did not say anything inconsistent with the Strzok interview 302; rather, he said he wasn’t sure where his knowledge came from.

Mr. Gowdy. Who is Christopher Steele? Well, before I go to that, let me ask you this.

At any — who interviewed General Flynn, which FBI agents?

Mr. Comey. My recollection is two agents, one of whom was Pete Strzok and the other of whom is a career line agent, not a supervisor.

Mr. Gowdy. Did either of those agents, or both, ever tell you that they did not adduce an intent to deceive from their interview with General Flynn?

Mr. Comey. No.

Mr. Gowdy. Have you ever testified differently?

Mr. Comey. No.

Mr. Gowdy. Do you recall being asked that question in a HPSCI hearing?

Mr. Comey. No. I recall — I don’t remember what question I was asked. I recall saying the agents observed no indicia of deception, physical manifestations, shiftiness, that sort of thing.

Mr. Gowdy. Who would you have gotten that from if you were not present for the interview?

Mr. Comey. From someone at the FBI, who either spoke to — I don’t think I spoke to the interviewing agents but got the report from the interviewing agents.

Mr. Gowdy. All right. So you would have, what, read the 302 or had a conversation with someone who read the 302?

Mr. Comey. I don’t remember for sure. I think I may have done both, that is, read the 302 and then spoke to people who had spoken to the investigators themselves. It’s possible I spoke to the investigators directly. I just don’t remember that.

Mr. Gowdy. And, again, what was communicated on the issue of an intent to deceive? What’s your recollection on what those agents relayed back?

Mr. Comey. My recollection was he was — the conclusion of the investigators was he was obviously lying, but they saw none of the normal common indicia of deception: that is, hesitancy to answer, shifting in seat, sweating, all the things that you might associate with someone who is conscious and manifesting that they are being — they’re telling falsehoods. There’s no doubt he was lying, but that those indicators weren’t there.

Mr. Gowdy. When you say “lying,” I generally think of an intent to deceive as opposed to someone just uttering a false statement.

Mr. Comey. Sure.

Mr. Gowdy. Is it possible to utter a false statement without it being lying?

Mr. Comey. I can’t answer — that’s a philosophical question I can’t answer.

Mr. Gowdy. No, I mean, if I said, “Hey, look, I hope you had a great day yesterday on Tuesday,” that’s demonstrably false.

Mr. Comey. That’s an expression of opinion.

Mr. Gowdy. No, it’s a fact that yesterday was —

Mr. Comey. You hope I have a great day —

Mr. Gowdy. No, no, no, yesterday was not Tuesday.

Mr. Gowdy. And, again — because I’m afraid I may have interrupted you, which I didn’t mean to do — your agents, it was relayed to you that your agents’ perspective on that interview with General Flynn was what? Because where I stopped you was, you said: He was lying. They knew he was lying, but he didn’t have the indicia of lying.

Mr. Comey. Correct. All I was doing was answering your question, which I understood to be your question, about whether I had previously testified that he — the agents did not believe he was lying. I was trying to clarify. I think that reporting that you’ve seen is the product of a garble. What I recall telling the House Intelligence Committee is that the agents observed none of the common indicia of lying — physical manifestations, changes in tone, changes in pace — that would indicate the person I’m interviewing knows they’re telling me stuff that ain’t true. They didn’t see that here. It was a natural conversation, answered fully their questions, didn’t avoid. That notwithstanding, they concluded he was lying.

Mr. Gowdy. Would that be considered Brady material and hypothetically a subsequent prosecution for false statement?

Mr. Comey. That’s too hypothetical for me. I mean, interesting law school question: Is the absence of incriminating evidence exculpatory evidence? But I can’t answer that question. [my emphasis]

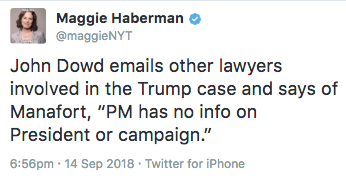

What may best explains this exchange is that, when it happened, Comey had never seen the Strzok 302, he had just seen the original one, but Gowdy had seen both. That would be consistent with Andrew McCabe’s testimony to HPSCI, which acknowledged that the Agents didn’t detect deception but knew Flynn’s statements did not match the FISA transcript.

McCabe confirmed the interviewing agent’s initial impression and stated that the “conundrum that we faced on their return from the interview is that although [the agents] didn’t detect deception in the statements that he made in the interview … the statements were inconsistent with our understanding of the conversation that he had actually had with the ambassador.”

Gowdy may be suggesting that the original 302 was unfair because it did not admit how well Flynn snookered the FBI’s top Counterintelligence Agent. But that detail may not be something Comey is even aware of, because it only got written down after he had been fired. That would explain why Flynn wouldn’t want that original one disclosed, because it might make clear that the FBI immediately recognized his claims to be false, even if they didn’t know (before doing the requisite follow-up) why he lied.

One thing we do know: there are two (related) criminal investigations that have come out of Mike Flynn’s interview. The first, into his lies, and the second, into Trump’s efforts to keep him on in spite of his lies by firing the FBI Director.

While we can’t say for sure (and Mueller’s office would not comment in response to my questions when I asked if something like this explained the 302), one possible explanation for why we’re seeing just this 302 is it’s the only one that makes Flynn look good.

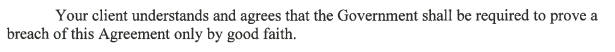

Update: As JL notes, the Mueller filing makes it clear that the 302 is neither from the Flynn investigation nor from an investigation into Strzok’s conduct.

Strzok was interviewed on July 19, 2017, in relation to other matters, not as part of the investigation of the defendant or any investigation of Strzok’s conduct.

As I disclosed in July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.