In his reply filing in the fight over what evidence will be submitted at his trial, Michael Sussmann confirmed something I’ve long suspected: John Durham has not provided Sussmann with the discovery Durham would need to have provided to present his own conspiracy theories at trial without risking a major discovery violation.

Were the Special Counsel to try to suggest that Mr. Sussmann and Mr. Steele engaged in a common course of conduct, that would open the door to an irrelevant mini-trial about the accuracy of Mr. Steele’s allegations about Mr. Trump’s ties to Russia—something that, like the Alfa Bank allegations, many experts continue to believe in, and about which the Special Counsel has tellingly failed to produce any significant discovery.

Sussmann dropped this in the filing without fanfare. But it is clear notice that if Durham continues down the path he is headed, he may face discovery sanctions down the road.

I explained why that’s true in these two posts. A core tenet of Durham’s conspiracy theories is that the only reason one would use proven cybersecurity methods to test certain hypotheses about Donald Trump would be for malicious political reasons. Here’s how Durham argued that in his own reply.

As the Government will demonstrate at trial, it was also the politically-laden and ethically-fraught nature of this project that gave Tech Executive-1 and the defendant a strong motive to conceal the origins of the Russian Bank-1 allegations and falsely portray them as the organic discoveries of concerned computer scientists.

There’s no external measure for what makes one thing political and makes another thing national security. But if this issue were contested, I assume that Sussmann would point, first, to truth as a standard. And as he could point out, many of the hypotheses April Lorenzen tested, which Durham points to as proof the project was malicious and political, turned out to be true. They were proven to be true by DOJ. Some of those true allegations involved guilty pleas to crimes, including FARA, explicitly designed to protect national security; another involved Roger Stone’s guilty verdict on charges related to his cover-up of his potential involvement in a CFAA hacking case.

DOJ (under the direction of Trump appointee Rod Rosenstein, who in those very same years was Durham’s direct supervisor) has already decided that John Durham is wrong about these allegations being political. Sussmann has both truth and DOJ’s backing on his side that these suspicions, if proven true (as they were), would be a threat to national security. Yet Durham persists in claiming to the contrary.

Here’s the evidence proving these hypotheses true that Durham has withheld in discovery:

The researchers were testing whether Richard Burt was a back channel to the Trump campaign. And while Burt’s more substantive role as such a (Putin-ordered) attempt to establish a back channel came during the transition, it is a fact that Burt was involved in several events earlier in the campaign at which pro-Russian entities tried to cultivate the campaign, including Trump’s first foreign policy speech. Neither Burt nor anyone else was charged with any crime, but Mueller’s 302s involving the Center for National Interest — most notably two very long interviews with Dmitri Simes (one, updated, two, updated), which were still under investigation in March 2020 — reflect a great deal of counterintelligence interest in the organization.

The researchers were also testing whether people close to Trump were laundering money from Putin-linked Oligarchs through Cyprus. That guy’s name is Paul Manafort, with the assistance of Rick Gates. Indeed, Manafort was ousted from the campaign during the period researchers were working on the data in part to distance the campaign from that stench (though it didn’t stop Trump from pardoning Manafort).

A more conspiratorial Lorenzen hypothesis (at least on its face) was that one of the family members of an Alfa Bank oligarch might be involved — maybe a son- or daughter-in-law. And in fact, German Khan’s son-in-law Alex van der Zwaan was working with Gates and Konstantin Kilimnik in precisely that time period to cover up Manafort’s ties to those Russian-backed oligarchs.

Then there was the suspicion — no doubt driven, on the Democrats’ part, by the correlation between Trump’s request to Russia for more hacking and the renewed wave of attacks that started hours later — that Trump had some back channel to Russia.

It turns out there were several. There was the aforementioned Manafort, who in the precise period when Rodney Joffe started more formally looking to see if there was a back channel, was secretly meeting at a cigar bar with alleged Russian spy Konstantin Kilimnik discussing millions of dollars in payments involving Russian-backed oligarchs, Manafort’s plan to win the swing states, and an effort to carve up Ukraine that leads directly to Russia’s current invasion.

That’s the kind of back channel researchers were using proven cybersecurity techniques to look for. They didn’t confirm that one — but their suspicion that such a back channel existed proved absolutely correct.

Then there’s the Roger Stone back channel with Guccifer 2.0. Again, in this precise period, Stone was DMing with the persona. But the FBI obtained at least probable cause that Stone’s knowledge of the persona went back much further, back to even before the persona went public in June 2016. That’s a back channel that remained under investigation, predicated off of national security crimes CFAA, FARA, and 18 USC 951, at least until April 2020 and one that, because of the way Stone was scripting pro-Russian statements for Trump, might explain Trump’s “Russia are you listening” comment. DOJ was still investigating Stone’s possible back channel as a national security concern well after Durham was appointed to undermine that national security investigation by deeming it political.

Finally, perhaps the most important back channel — for Durham’s purposes — was Michael Cohen. That’s true, in part, because the comms that Cohen kept lying to hide were directly with the Kremlin, with Dmitri Peskov. That’s also true because on his call to a Peskov assistant, Cohen laid out his — and candidate Donald Trump’s — interest in a Trump Tower Moscow deal that was impossibly lucrative, but which also assumed the involvement of one or another sanctioned bank as well as a former GRU officer. That is, not only did Cohen have a back channel directly with the Kremlin he was trying to hide, but it involved Russian banks that were far more controversial than the Alfa Bank ties that the researchers were pursuing, because the banks had been deemed to have taken actions that threatened America’s security.

This back channel is particularly important, though, because in the same presser where Trump invited Russia to hack his opponent more, he falsely claimed he had decided against pursuing any Trump Organization developments in Russia.

Russia that wanted to put a lot of money into developments in Russia. And they wanted us to do it. But it never worked out.

Frankly I didn’t want to do it for a couple of different reasons. But we had a major developer, particular, but numerous developers that wanted to develop property in Moscow and other places. But we decided not to do it.

The researchers were explicitly trying to disprove Trump’s false claim that there were no ongoing business interests he was still pursuing with Russia. And this is a claim that Michael Cohen not only admitted was false and described recognizing was false when Trump made this public claim, but described persistent efforts on Trump’s part to cover up his lie, continuing well into his presidency.

For almost two years of Trump’s Administration, Trump was lying to cover up his efforts to pursue an impossibly lucrative real estate deal that would have required violating or eliminating US sanctions on Russia. That entire time, Russia knew Trump was lying to cover up those back channel communications with the Kremlin. That’s the kind of leverage over a President that all Americans should hope to avoid, if they care about national security. That’s precisely the kind of leverage that Sally Yates raised when she raised concerns about Mike Flynn’s public lies about his own back channel with Russia. Russia had that leverage over Trump long past the time Trump limped out of a meeting with Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, to which Trump had brought none of the aides who would normally sit in on a presidential meeting, looking like a beaten puppy.

Durham’s failures to provide discovery on this issue are all the more inexcusable given the fights over privilege that will be litigated this week.

As part of the Democrats’ nesting privilege claims objecting to Durham’s motion to compel privileged documents, Marc Elias submitted a declaration describing how, given his past knowledge and involvement defending against conspiracy theory attacks on past Democratic presidential candidates launched by Jerome Corsi and Donald Trump, and given Trump’s famously litigious nature, he believed he needed expertise on Trump’s international business ties to be able to advise Democrats on how to avoid eliciting such a lawsuit from Trump. (Note, tellingly, Durham’s motion to compel doesn’t mention a great deal of accurate Russian-language research by Fusion — to which Nellie Ohr was just one of a number of contributors — that was never publicly shared nor debunked as to quality.)

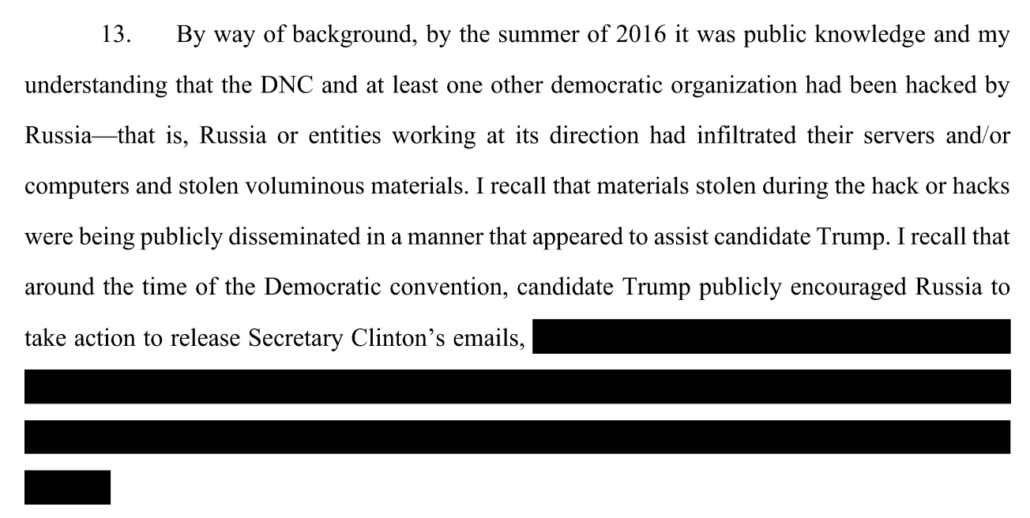

There are four redacted passages that describe the advice he provided; he is providing these descriptions ex parte for Judge Cooper to use to assess the Democrats’ privilege claims. Two short ones probably pertain to the scope of Perkins Coie’s relationship with the Democratic committees. Another short one likely describes Elias’ relationship, and through him, Fusion’s, with the oppo research staff on the campaign. But the longest redaction describing Elias’ legal advice, one that extends more than five paragraphs and over a page and a half, starts this way:

That is, the introduction to Elias’ description of the privilege claims tied to the Sussmann trial starts from Trump’s request of Russia to hack Hillary. Part of that sentence and the balance of the paragraph is redacted — it might describe that immediately after Trump made that request, the Russians fulfilled his request — but the redacted paragraph and the balance of the declaration presumably describes what legal advice he gave Hillary as she faced a new onslaught of Russian hacking attempts that seemingly responded to her opponent’s request for such hacking.

Given what Elias described about his decision to hire Fusion, part of that discussion surely explains his effort to assess an anomaly identified independently by researchers that reflected unexplained traffic between a Trump marketing server and a Russian bank. Elias probably described why it was important for the Hillary campaign to assess whether this forensic data explained why Russian hackers immediately responded to Trump’s request to hack her.

As I have noted, in past filings Durham didn’t even consider the possibility that Elias might discuss the renewed wave of hacking that Hillary’s security personnel IDed in real time with Sussmann, Perkins Coie’s cybersecurity expert.

It’s a testament to how deep John Durham is in his conspiracy-driven rabbit hole that he assumes a 24-minute meeting between Marc Elias and Michael Sussmann on July 31, 2016 to discuss the “server issue” pertained to the Alfa Bank allegations. Just days earlier, after all, Donald Trump had asked Russia to hack Hillary Clinton, and within hours, Russian hackers obliged by targeting, for the first time, Hillary’s home office. Someone who worked in security for Hillary’s campaign told me that from his perspective, the Russian attacks on Hillary seemed like a series of increasing waves of attacks, and the response to Trump’s comments was one of those waves (this former staffer documented such waves of attack in real time). The Hillary campaign didn’t need Robert Mueller to tell them that Russia seemed to respond to Trump’s request by ratcheting up their attacks, and Russia’s response to Trump would have been an urgent issue for the lawyer in charge of their cybersecurity response.

It’s certainly possible this reference to the “server” issue pertained to the Alfa Bank allegations. But Durham probably doesn’t know; nor do I. None of the other billing references Durham suggests pertain to the Alfa Bank issue reference a server.

Durham took a reference that might pertain to a discussion of a correlation between Trump’s ask and a renewed wave of Russian attacks on Hillary (or might pertain to the Alfa Bank anomaly), and assumed instead it was proof that Hillary was manufacturing unsubstantiated dirt on her opponent. He never even considered the legal challenges someone victimized by a nation-state attack, goaded by her opponent, might face.

And yet, given the structure of that redaction from Elias, that event is the cornerstone of the privilege claims surrounding the Alfa Bank allegations.

Because of all the things I laid out in this post, Judge Cooper may never have to evaluate these privilege claims at all. To introduce privileged evidence, Durham has to first withstand:

- Denial because his 404(b) notice asking to present it was late, and therefore forfeited

- Denial because Durham’s motion to compel violated local rules and grand jury process, in some ways egregiously

- Rejection because most of the communications over which the Democrats have invoked privilege are inadmissible hearsay

- The inclusion or exclusion of the testimony of Rodney Joffe, whose privilege claims are the most suspect of the lot, but whose testimony would make the communications Durham deems to be most important admissible

Cooper could defer any assessment of these privilege claims until he decides these other issues and, for one or several procedural reasons, simply punt the decision entirely based on Durham’s serial failures to follow the rules.

Only after that, then, would Cooper assess a Durham conspiracy theory for which Durham himself admits he doesn’t have proof beyond a reasonable doubt. As part of his bid to submit redacted and/or hearsay documents as exhibits under a claim that this all amounted to a conspiracy (albeit one he doesn’t claim was illegal), Durham argues that unless he can submit hearsay and privileged documents, he wouldn’t otherwise have enough evidence to prove his conspiracy theory.

Nor is evidence of this joint venture gratuitous or cumulative of other evidence. Indeed, the Government possesses only a handful of redacted emails between the defendant and Tech Executive-1 on these issues. And the defendant’s billing records pertaining to the Clinton Campaign, while incriminating, do not always specify the precise nature of the defendant’s work.

Accordingly, presenting communications between the defendant’s alleged clients and third parties regarding the aforementioned political research would hardly amount to a “mini-trial.” (Def. Mot. at 20). Rather, these communications are among the most probative and revealing evidence that the Government will present to the jury. Other than the contents of privileged communications themselves (which are of course not accessible to the Government or the jury), such communications will offer some of the most direct evidence on the ultimate question of whether the defendant lied in stating that he was not acting for any other clients.

In short, because the Government here must prove the existence of client relationships that are themselves privileged, it is the surrounding events and communications involving these clients that offer the best proof of those relationships.

Moreover, even if the Court were to find that no joint venture existed, all of the proffered communications are still admissible because, as set forth in the Government’s motions, they are not being offered to prove the truth of specific assertions. Rather, they are being offered to prove the existence of activities and relationships that led to, and culminated in, the defendant’s meeting with the FBI. Even more critically, the very existence of these written records – which laid bare the political nature of the exercise and the numerous doubts that the researchers had about the soundness of their conclusions – gave the defendant and his clients a compelling motive, separate and apart from the truth or falsity of the emails themselves, to conceal the identities of such clients and origins of the joint venture. Accordingly, they are not being offered for their truth and are not hearsay.

This passage (which leads up to a citation from one of the Georgia Tech researchers to which Sussmann was not privy that the frothers have spent the weekend drooling over) is both a confession and a cry for help.

In it, Durham admits he doesn’t actually have proof that the conspiracy he is alleging is the motive behind Michael Sussmann’s alleged lie.

He’s making this admission, of course, while hiding the abundant evidence — evidence he didn’t bother obtaining before charging Sussmann — that Sussmann and Joffe acceded to the FBI request to help kill the NYT story, which substantiates Sussmann’s stated motive.

And then, in the same passage, Durham is pointing to that absence of evidence to justify using that same claimed conspiracy for which he doesn’t have evidence to pierce privilege claims to obtain the evidence he doesn’t have. It’s a circular argument and an admission that all the claims he has been making since September are based off his beliefs about what must be there, not what he has evidence for.

Thus far the researchers’ beliefs about what kind of back channels they might find between Trump and Russia have far more proof than Durham’s absence of evidence.

Again, Durham doesn’t even claim that such a conspiracy would be illegal (much less chargeable under the statute of limitations), which is why he didn’t do what he could have had he been able to show probable cause that a crime had been committed: obtaining the communications with a warrant and using a filter team. Bill Barr’s memoir made it quite clear that he appointed Durham not because a crime had been committed, but because he wanted to know how a “bogus scandal” in which DOJ found multiple national security crimes started. ”Even after dealing with the Mueller report, I still had to launch US Attorney John Durham’s investigation into the genesis of this bogus scandal.” In his filing, Durham confesses to doing the same, three years later: using his feelings about a “bogus scandal” to claim a non-criminal conspiracy that he hopes might provide some motive other than the one — national security — that DOJ has already confirmed.

An absolutely central part of Durham’s strategy to win this trial is to present his conspiracy theories, whether by belatedly piercing privilege claims he should have addressed before charging Sussmann (even assuming he’ll find what he admits he doesn’t have proof is there), or by presenting his absence of evidence and claiming it is evidence. He will only be permitted to do if Judge Cooper ignores all his rule violations and grants him a hearsay exception.

But if he manages to present his conspiracy theories, Sussmann can immediately pivot and point out all the evidence in DOJ’s possession that proves not just that the suspicions Durham insists must be malicious and political in fact proved to be true, but also that DOJ — his former boss! — already deemed these suspicions national security concerns that in some cases amounted to crimes.

John Durham’s entire trial strategy consists of claiming that it was obviously political to investigate a real forensic anomaly to see whether it explained why Russia responded to Trump’s call for more hacks by renewing their attack on Hillary. He’s doing so while withholding abundant material evidence that DOJ already decided he’s wrong.

So even if he succeeds, even if Cooper grants him permission to float his conspiracy theories and even if they were to succeed at trial, Sussmann would have immediate recourse to ask for sanctions, pointing to all the evidence in DOJ’s possession that Durham’s claims of malice were wrong.

Update: The bad news I’m still working through my typos, with your help, including getting the name of Dmitri Simes’ organization wrong. The good news is the typos are probably due to being rushed out to cycle in the sun, so I have a good excuse.

Update: Judge Cooper has issued an initial ruling on Durham’s expert witness. It limits what Durham presents to the FBI investigation (excluding much of the CIA investigation he has recently been floating), and does not permit the expert to address whether the data actually did represent communications between Trump and Alfa Bank unless Sussmann either affirmatively claims it did or unless Durham introduced proof that Sussmann knew the data was dodgy.

Finally, the Court takes a moment to explain what could open the door to further evidence about the accuracy of the data Mr. Sussmann provided to the FBI. As the defense concedes, such evidence might be relevant if the government could separately establish “what Mr. Sussmann knew” about the data’s accuracy. Data Mot. at 3. If Sussmann knew the data was suspect, evidence about faults in the data could possibly speak to “his state of mind” at the time of his meeting with Mr. Baker, id., including his motive to conceal the origins of the data. By contrast, Sussmann would not open the door to further evidence about the accuracy of the data simply by seeking to establish that he reasonably believed the data were accurate and relied on his associates’ representations that they were. Such a defense theory could allow the government to introduce evidence tending to show that his belief was not reasonable—for instance, facially obvious shortcomings in the data, or information received by Sussmann indicating relevant deficiencies.

Ultimately, Cooper is treating this (as appropriate given the precedents in DC) as a question of Sussmann’s state of mind.

Importantly, this is what Cooper says about Durham blowing his deadline (which in this case was a deadline of comity, not trial schedule): he’s going to let it slide, in part because Sussmann does not object to the narrowed scope of what the expert will present.

Mr. Sussmann also urges the Court to exclude the expert testimony on the ground that the government’s notice was untimely and insufficiently specific. See Expert Mot. at 6–10; Fed. R. Crim. P. 16(a)(1)(G). Because the Court will limit Special Agent Martin’s testimony largely to general explanations of the type of technical data that has always been part of the core of this case—much of which Mr. Sussmann does not object to—any allegedly insufficient or belated notice did not prejudice him. See United States v. Mohammed, No. 06-cr-357, 2008 WL 5552330, at *3 (D.D.C. May 6, 2008) (finding that disclosure nine days before trial did not prejudice defendant in part because its subject was “hardly a surprise”) (citing United States v. Martinez, 476 F.3d 961, 967 (D.C. Cir. 2007)).

This suggests Cooper may be less willing to let other deadlines slide, such as the all-important 404(b) one.