The Inadequate Declination Discussions in Both Special Counsel Reports

In a post in November and a podcast appearance with Harry Litman, I argued that the Special Counsel regulations mandating that prosecutors describe declination decisions, as well as prosecution decisions, might produce the most interesting part of Jack Smith’s report.

Closing documentation. At the conclusion of the Special Counsel’s work, he or she shall provide the Attorney General with a confidential report explaining the prosecution or declination decisions reached by the Special Counsel.

After all, Robert Hur wrote a humdinger of a 388-page report that was nothing but declination decisions.

But in my opinion, neither Jack Smith nor David Weiss adequately fulfilled the terms of that mandate.

To be sure, Jack Smith did include several important sections describing declination decisions. As I laid out here, Smith described why prosecutors had not charged Trump with insurrection, the sole charge that could have disqualified him from returning to the presidency. A footnote explained that prosecutors had considered charging Trump under the Anti-Riot Act, but courts have struck down parts of it. The footnote also explained that because prosecutors “did not develop proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the conspirators specifically agreed to threaten force or intimidation against federal officers,” (presumably including Mike Pence), they did not charge Trump with conspiracy to injure an officer of the United States.

In a separate paragraph, Smith provided an unsatisfying answer about why he didn’t charge any of Trump’s co-conspirators.

Before the Department concluded that this case must be dismissed, the Office had made a preliminary determination that the admissible evidence could justify seeking charges against certain co-conspirators. The Office had also begun to evaluate how to proceed, including whether any potential charged case should be joined with Mr. Trump’s or brought separately. Because the Office reached no final conclusions and did not seek indictments against anyone other than Mr. Trump–the head of the criminal conspiracies and their intended beneficiary–this Report does not elaborate further on the investigation and preliminary assessment of uncharged individuals. This Report should not be read to allege that any particular person other than Mr. Trump committed a crime, nor should it be read to exonerate any particular person.

My suspicion is that the prosecution, which included two prosecutors who dealt with the aftermath of Trump pardoning his way out of criminal exposure in the Russian investigation, recognized it was not worth charging others until such time as Trump couldn’t pardon their silence. That is consistent with the seeming late addition of a Ken Chesebro interview, which seems to reflect his troubled efforts to cooperate in state cases. But if this investigation looked like it did because of Trump’s past success at pardoning his way out of criminal exposure, it would be really useful to explain that.

It would have been useful, too, to point out that the same Speech and Debate protections that created a 16-month delay in obtaining texts from Scott Perry’s phone also made it impossible to charge any of the Members of Congress who facilitated Trump’s coup attempt. Those who don’t understand the breadth of Speech and Debate need to be told that.

So Smith did include some of his declination decisions, but some of those discussions are less than satisfying.

But there are two areas where more might have been useful. For example, for some time, prosecutors investigated whether Trump used funds raised for election integrity on other things, like providing big contracts to people who had remained loyal to him. If Trump defrauded his rubes but for some reason prosecutors couldn’t charge him for it, it would be useful to lay that out. That prong of the investigation is unmentioned in the report, which in many respects appears designed to avoid antagonizing Trump.

There’s a more important discussion that does appear in the report, but which is not treated as a prosecutorial decision. In the section on Litigation Challenges, Smith includes a long discussion titled, “Threats and Intimidation of Witnesses.”

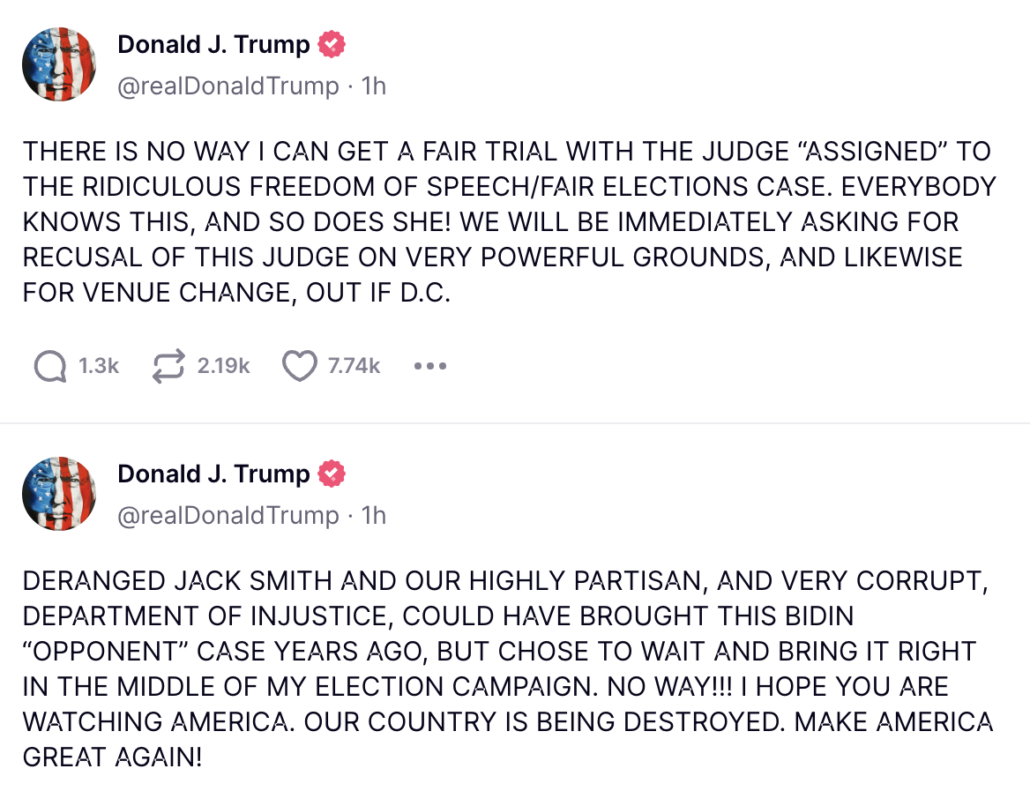

A significant challenge that the Office faced after Mr. Trump’s indictment was his ability and willingness to use his influence and following on social media to target witnesses, courts, and Department employees, which required the Office to engage in time-consuming litigation to protect witnesses from threats and harassment.

Mr. Trump’s resort to intimidation and harassment during the investigation was not new, as demonstrated by his actions during the charged conspiracies. A fundamental component of Mr. Trump’s conduct underlying the charges in the Election Case was his pattern of using social media-at the time, Twitter-to publicly attack and seek to influence state and federal officials, judges, and election workers who refused to support false claims that the election had been stolen or who otherwise resisted complicity in Mr. Trump’s scheme. After Mr. Trump publicly assailed these individuals, threats and harassment from his followers inevitably followed. See ECF No. 57 at 3 (one witness identifying Mr. Trump’s Tweets about him as the cause of specific and graphic threats about his family, and a public official providing testimony that after Mr. Trump’s Tweets, he required additional police protection). In the context of the attack on the Capitol on January 6, Mr. Trump acknowledged that his supporters “listen to [him] like no one else.” 260

The same pattern transpired after Mr. Trump’s indictment in the Election Case. As the D.C. Circuit later found, Mr. Trump “repeatedly attacked those involved in th[e] case through threatening public statements, as well as messaging daggered at likely witnesses and their testimony,” Trump, 88 F.4th at 1010. Those attacks had “real-time, real-world consequences,” exposing “those on the receiving end” to “a torrent of threats and intimidation” and turning their lives “upside down.” Id. at 1011-1012. The day after his arraignment, for example, Mr. Trump posted on the social media application Truth Social, “IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I’M COMING AFTER YOU!” Id. at 998. The next day, “one of his supporters called the district court judge’s chambers and said: ‘Hey you stupid slave n[****]r[.] * * * If Trump doesn’t get elected in 2024, we are coming to kill you, so tread lightly b[***]h. * * * You will be targeted personally, publicly, your family, all of it.'” Id. 26 l Mr. Trump also “took aim at potential witnesses named in the indictment,” id. at 998-999, and “lashed out at government officials closely involved in the criminal proceeding,” as well as members of their families, id. at 1010-1011.

To protect the integrity of the proceedings, on September 5, 2023, the Office filed a motion seeking an order pursuant to the district court’s rules restricting certain out-of-court statements by either party. See ECF No. 57; D.D.C. LCrR 57.7(c). The district court heard argument and granted the Office’s motion, finding that Mr. Trump’s public attacks “pose a significant and immediate risk that (1) witnesses will be intimidated or otherwise unduly influenced by the prospect of being themselves targeted for harassment or threats; and (2) attorneys, public servants, and other court staff will themselves become targets for threats and harassment.” ECF No. 105 at 2. Because no “alternative means” could adequately address these “grave threats to the integrity of these proceedings,” the court prohibited the parties and their counsel from making public statements that “target (1) the Special Counsel prosecuting this case or his staff; (2) defense counsel or their staff; (3) any of this court’s staff or other supporting personnel; or (4) any reasonably foreseeable witness or the substance of their testimony.” Id at 3. The court emphasized, however, that Mr. Trump remained free to make “statements criticizing the government generally, including the current administration or the Department of Justice; statements asserting that [he] is innocent of the charges against him, or that his prosecution is politically motivated; or statements criticizing the campaign platforms or policies of[his] current political rivals.” Id. at 3.

Mr. Trump appealed, and the D.C. Circuit affirmed in large part, finding that Mr. Trump’s attacks on witnesses in this case posed “a significant and imminent threat to individuals’ willingness to participate fully and candidly in the process, to the content of their testimony and evidence, and to the trial’s essential truth-finding function,” with “the undertow generated by such statements” likely to “influence other witnesses” and deter those “not yet publicly identified” out of “fear that, if they come forward, they may well be the next target.” Trump, 88 F.4th at 1012-1013. Likewise, “certain speech about counsel and staff working on the case poses a significant and imminent risk of impeding the adjudication of th[e] case,” since “[m]essages designed to generate alarm and dread; and to trigger extraordinary safety precautions, will necessarily hinder the trial process and slow the administration of justice.” Id at 1014. [snip]

Sure, this was treated as a litigation issue. But, in theory, there were alternative means to prevent Trump from attacking witnesses. When Jan6er Brandon Fellows — like Trump accused of obstruction — made similar threats, but without the big mouthpiece that makes it so dangerous, Trump appointee Trevor McFadden put him in an extended pretrial detention. You were never going to be able to treat Trump like a normal pretrial defendant, but shouldn’t you make that point?

More importantly, witness intimidation is also a crime. It’s the same statute, 18 USC 1512, under which Trump was charged. In fact, when Trump challenged his gag before the DC Circuit, Patricia Millett asked John Sauer where criminal witness tampering ended and the kinds of threatening language he was using began (and she treated the means by which Trump makes threats at length in her opinion upholding much of the gag).

Judge Millett then tries a different tack. She wants to know if Sauer concedes that a trial judge can constitutionally limit a criminal defendant’s speech in any way beyond what’s already limited by criminal laws, like the witness tampering statute. She notes that the Supreme Court’s conception of even the clear and present danger test is still that it is a balancing test that requires consideration of the weighty constitutional interest in protecting the integrity of a criminal trial as well as the First Amendment interests of the defendant.

Sauer responds that Brown guarantees the defendant “absolute freedom” on core political speech.

“So there is no balance,” says Judge Millett. She adds that calling it “core political speech” begs the question of whether it is in fact political speech or whether it is speech “aimed at derailing or corrupting the criminal justice process.” Sauer responds that Trump’s campaign speech is “inextricably entwined” with freely responding to the entire election interference prosecution.

Trump’s ability and willingness to sic mobs on all his enemies is the core of his conduct, both on January 6, during this litigation, and going forward. And the incoming Solicitor General argued that such threats and intimidation is “core political speech.”

It is the reason he threatens democracy in America.

Yet in discussing his thinking about how to deal with the threat posed by Trump’s threats, Smith didn’t even discuss why Trump could threaten Mike Pence in advance of a trial in which Pence would be expected to testify about how Trump almost got him assassinated without being charged with witness tampering.

With no awareness, Trump’s witness tampering became a litigation challenge, rather than the crime it might be treated as for anyone else.

Which brings me to David Weiss’ report, which is nothing short of pee my pants hysterical. It is riddled with procedural and evidentiary problems, and wild refashionings of the public record. Though I commend Derek Hines for finally ending his practice of fabricating what Hunter Biden’s memoir says, fabrications he relied on repeatedly to convince Judge Noreika there was no selective prosecution and to convince the jury of Hunter’s guilt; I hope to return to this to show that, by abandoning his fabrications, Hines actually proves he didn’t have the evidence to prosecute Hunter he claimed to have.

Much of the report is a “doth protest too much” effort to claim that the investigation wasn’t riddled with political influence. But tellingly and fucking hilariously, all those complaints are directed to Joe Biden, including this accusation:

Politicians who attack the decisions of career prosecutors as politically motivated when they disagree with the outcome of a case undermine the public’s confidence in our criminal justice system.

Weiss blames Joe Biden for undermining the public’s confidence in our criminal justice system even though his discussions of Hunter Biden’s claims of selective prosecution, Weiss made no mention of the very specific references Hunter made to Trump’s interventions in the case, including Trump’s public attack on the outcome of the original plea deal that contributed, according to Weiss’ own sworn testimony, to threats that led him to worry for the safety of his family.

“Wow! The corrupt Biden DOJ just cleared up hundreds of years of criminal liability by giving Hunter Biden a mere ‘traffic ticket.’ Our system is BROKEN!”67

“A ‘SWEETHEART’ DEAL FOR HUNTER (AND JOE), AS THEY CONTINUE THEIR QUEST TO ‘GET’ TRUMP, JOE’S POLITICAL OPPONENT. WE ARE NOW A THIRD WORLD COUNTRY!”68

“The Hunter/Joe Biden settlement is a massive COVERUP & FULL SCALE ELECTION INTERFERENCE ‘SCAM’ THE LIKES OF WHICH HAS NEVER BEEN SEEN IN OUR COUNTRY BEFORE. A ‘TRAFFIC TICKET,’ & JOE IS ALL CLEANED UP & READY TO GO INTO THE 2024 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION. . . .” 69

[snip]

“Weiss is a COWARD, a smaller version of Bill Barr, who never had the courage to do what everyone knows should have been done. He gave out a traffic ticket instead of a death sentence. . . . ”

After spending much of his report attacking Joe Biden, Weiss claimed, “when politicians expressed opinions about my conduct, I ignored them because they were irrelevant.”

I hope to lay out all the other hilarity before such time as Weiss gets dragged before Congress.

Weiss’ charging decisions have flaws. My favorite is how, after dutifully laying out that Principles of Federal Prosecution require considering whether the suspect “is subject to effective prosecution in another jurisdiction,”

Even when a prosecutor determines that the person has committed a federal offense and that the evidence is sufficient to obtain a conviction, the Principles require that he also assess whether three other factors exist that may counsel against prosecution:

[snip]

(2) the person is subject to effective prosecution in another jurisdiction; or

Weiss then ignores the fact that Hunter was subject to charges in Delaware, which declined to prosecute.

It’s in the declinations, though, where David Weiss proves he’s falsely disclaiming selective prosecution. Several times, Weiss plays coy rather than explaining why he didn’t charge things, like tax crimes associated with 2014 and 2015, even though he stated under oath in November 2023 that he would have the “opportunity in the submission of a report to address such matters.”

19 26 U.S.C. § 6103(a) prohibits the disclosure of “return information,” which includes information disclosing “whether the taxpayer’s return was, is being, or will be examined or subject to other investigation or processing.” Id. § 6103(b)(2)(A). Accordingly, I cannot publicly discuss any other tax years that may have been under investigation. See Snider u. United States, 468 F.3d 500, 508 (8th Cir. 2006).

I assume Biden is happy that Weiss didn’t lay out how Weiss was still pursuing Kevin Morris’ support for Hunter even after the guilty verdicts (but as I’ll show one of his temporal games involves just that),

President Biden has chosen to issue a “Full and Unconditional Pardon” for Mr. Biden covering “those offenses against the United States which he has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 1, 2014 through December 1, 2024, including but not limited to all offenses charged or prosecuted (including any that have resulted in convictions) by Special Counsel David C. Weiss in Docket No. 1:23-cr-00061-MN in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware and Docket No. 2:23-CR-00599-MCS-1 in the United States District Court for the Central District of California.” 152 Accordingly, I cannot make any additional charging decisions as to Mr. Biden’s conduct during that time period. It would be inappropriate to discuss whether additional charges are warranted.

But Weiss didn’t have the integrity, as Jack Smith did, to admonish, “This Report should not be read to allege that any particular person other than Mr. Trump committed a crime, nor should it be read to exonerate any particular person.” He lets the rabid mobs believe they are.

It’s in how Weiss buries his own selective prosecution where his declinations are most corrupt. In his letter conveying the report to Merrick Garland, he describes that he is adhering to Department policy by not identifying uncharged third parties.

Therefore, in drafting this report, I was mindful of Department policies that caution restraint when publicly revealing information about uncharged third parties. Specifically, with respect to “public filings and proceedings,” Justice Manual § 9-27.760 provides that prosecutors “should remain sensitive to the privacy and reputation interests of uncharged parties,” and that it is generally “not appropriate to identify . . . a party unless that party has been publicly charged with the misconduct at issue.” 7 The Justice Manual also sets forth factors to guide the disclosure of information about uncharged individuals, such as their privacy, safety, and reputational interests; the potential effect of any statements on ongoing criminal investigations or prosecutions; whether public disclosure may advance significant law enforcement interests; and other legitimate and compelling governmental interests.

As a result, David Weiss doesn’t explain why he prosecuted Hunter Biden for lying on a gun form and he prosecuted Biden nut Alexander Smirnov for lying to his FBI handler in an attempt to frame Joe Biden, but he didn’t prosecute anyone from the gun store who allegedly engaged in the same kind of conduct that Hunter Biden and Alexander Smirnov did: make a false statement on a gun form and also coordinate a story in an effort to … create a political attack on Joe Biden during an election year.

The reasonable reasons why Weiss decided to immunize Ron Palimere yet charge Hunter all debunk much of the rest of his report, specifically with regards to deciding there was plenty of evidence to charge a gun crime in 2023, before entering into the failed plea deal. Either prosecutors knew Palimere had doctored the form when Weiss made that supposed prosecutorial decision, or (as he implied in court filings) he only discovered it when Hunter’s lawyers raised it, and he gave Palimere immunity so he could still win conviction against Hunter, in which case he never looked at the evidence before charging Hunter (which is consistent with virtually every other fact in the case).

Still, it’s selective prosecution. Prosecute the gun crime that Republicans — including Palimere — demanded be prosecuted, but immunize Palimere, who testified to treating other VIP customers similarly.

And Smith demonstrates that, contra Weiss, one can adhere to Justice Manual requirements yet still admit there was another suspected crime. In his section explaining why he didn’t charge Trump’s co-conspirators, he revealed that he did refer a subject of the investigation to another US Attorneys office.

In addition, the Office referred to a United States Attorney’s Office for further investigation evidence that an investigative subject may have committed unrelated crimes.

Weiss could have used a similar approach to describe that he immunized someone — someone who would pose an ongoing risk to the public if he continues to engage in the same behavior — for effectively the same crime for which he prosecuted Hunter Biden.

But that would give up his entire game.

Whatever else these Special Counsel reports reveal about our justice system, the blind spots both Special Counsels use to coddle Trump confirm that Special Counsels will never be able to hold Trump accountable for the existential threat he poses to democracy.