Conclusion To Series On Rights

Posts in this series

Conclusion to How Rights Went Wrong

In the last half of Jamal Greene’s book he gives us his explanation of a better way forward, and applies it to several controversial issues, including abortion and discrimination. Greene thinks that courts, especially SCOTUS, spend too much time on their made-up rules about about rights, instead of the rights themselves. He thinks all applicable rights claims have to be considered in rendering decisions and establishing remedies.

The Rodriguez case discussed in the last post is a good example. Kids are going to school with bats, but nothing can be done because of court-created rules designed to limit the reach of the Reconstruction Amendments. I think Greene is right about this.

I think that there are two problems underlying our current judicial approach that prevent Green’s ideas from being effectuated. First, immediately after the enactment of the Reconstruction Amendments SCOTUS limited their reach. The purported reason was preservation of federalism, as we see in The Slaughterhouse Cases. But that doesn’t explain the ferocity with which the Court attacked individual rights and especially Congressional action up to the 1930s, and then after a short respite, returned to the attack beginning in the Reagan era and continuing to the present.

This, I think, reflects a deep skepticism of democracy, whether in claims of individual rights against governments, or in concerted political action through the legislature. It seems SCOTUS has little respect for rights claims of ordinary people regardless of whether the rights arise through legislation or under the Constitution.

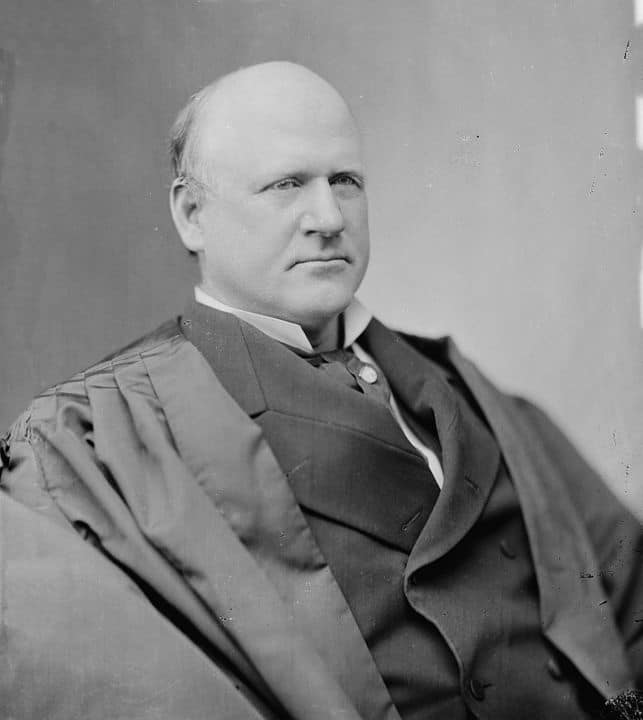

The judicial branch has always been a bastion of the privileged elites, who mostly like things the way they are. Powerful commercial interests are heavily over-represented, and have always been. Lewis Powell, the author of Rodriguez, is an example.

The second issue, I think, is the general unwillingness of the judicial system to make rulings requiring other branches to enforce. As an example consider Holmes’ 1902 decision in Giles v. Harris, discussed by Greene. Giles, a Black man, had been registered to vote in Alabama for years. The Alabama Constitution was changed to allow local election registrars to deny registration to people who lacked good character. Giles was not allowed to register under the new system. Ovrall, registration of Black men drooped to nearly zero. There is no doubt that this was a violation of the 15th Amendment. Holmes refused to do anything. One of his reasons was that “…the sheer scale of the conspiracy Giles was alleging exceeded the Court’s power to remedy it.” P. 49.

Courts have always been concerned about their ability to enforce their decrees, and rightly so. But that’s not an excuse for simply refusing to enforce rights. Courts are really good at collecting money. Creative use of this power is a great solution to weakness.

For example, in the Rodriguez case Powell could have given the school district a money judgment large enough to construct a new school, one less friendly to bats, and awarded further monetary damages necessary to bring the school’s textbooks up to date and deal with other issues. He could have imposed costs and attorney’s fees on the school district, and awarded the plaintiffs monetary damages for the injuries they suffered by going to school with bats and ripped up out-of-date textbooks. That would open the door to other under-funded schools in Texas to sue the State and local districts to equalize things. The legislature eventually would have been forced change the funding arrangement.

A third issue, most pornounced in the current panel of SCOTUS, is its effort to justify its decisions by newly created doctrines. The so-called Major Questions Doctrine is an example. This was apparently created for the purpose of thwarting government efforts to remedy serious emergencies pursuant to express legislative action. Another example is the absurd result in US v. Trump, where the loons expressly denied that they were looking at the facts of the actual case: Trump’s efforts to overthrow an election. Instead they insisted they had to make a rule for the ages.

This is preposterous because the right-wingers on the Court don’t have a problem throwing out cases and rules they don’t like.

There are many better ways forward, including Greene’s. But so what? All Republicans including those on SCOTUS are incorrigible. We can’t even get the current crop of geriatric Democrats to hold a hearing on the corruption we all know exists in the judicial system, ranging from the ethics violations of right-wing SCOTUS members to the scandalous judge-shopping of the creepy right wing, to the overtly political decisions of the District and Circuit Court in Fifth Circuit. The fact is that only sustained aggressive demands will ever change anything.

Conclusion To The Conclusion

In this series I’ve discussed three texts: The Evolution Of Agency by Michael Tomasello; Chapter 9 of The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt; and Greene’s thoughtful book.

Tomasello provided a look at the way we humans evolved. I think it hints at how we came to think about rights. He speculates that the earliest ancestors of humans were weaker, slower, more fragile, and had less sensitive eyes, ears and noses than their competitors. They survived by being more cooperative, more attuned to their group, more sensitive to the desires and emotions of individuals in the group. This increased receptiveness to others was the genesis and result of increasing brain size. The larger brain changed the bodies of women to enable birth babies with larger heads. That led to complications of birth. Dealing with those complications required more social cooperation. The longer dependency of the young also increased the demands of cooperation. These changes increased over time and eventually we became human. For a similar view, I recommend Eve by Cat Bohannon, which discusses evolution from the perspective of the female body and mind.

The importance of cooperation in this story leads me to speculate that rights are a way of maintaining individuality among creatures who are tightly bound for the sake of survival.

The Arendt selection says that rights are mutually guaranteed by equal citizens in a society. It also says that rights don’t matter unless there is some way to enforce and protect them. These are her conclusions about the last 200 years, not the earlier millenia.

Greene’s book tells us the story of our national attempt to insure our rights through the legislature and the judiciary, and the sad results.

I think everything we know and essentially all we think and think we know comes from other humans. That includes our rights. Some of us talk about natural rights, some about constitutional rights, some about human rights, some about God-given rights, but all of that comes from other humans and our own interpretations of their thinking. We draw from religions, philosophy, novels, catechisms, preachers, practical experience, our own emotions and sensitivities, laws, each other, our parents and teachers, our colleagues and our children.

But it’s always just us humans, trying to survive as individuals and as members of a group.

So I conclude with a question: how do you discuss questions of rights with people who believe that they possess the absolute unvarying truth?

none

none