It Turns Out CREDO Will Respond to Administration Subpoenas

It turns out CREDO will respond to simple administrative subpoenas.

That’s one thing their new Transparency Report — the first of its kind in the industry — reveals. They complied with 5 administrative subpoenas last year: 3 from the DEA, one from a police department, and one from a DA, a full third of all the disclosed requests they got and complied with.

So they’re not opposed, in principle, to information requests lacking any judicial review.

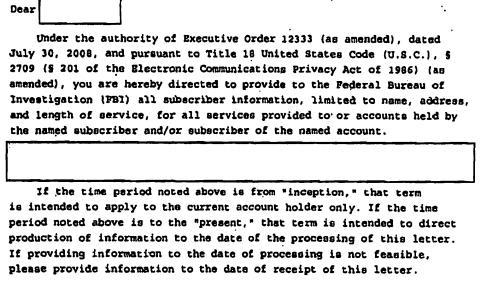

That’s not in the least bit surprising, but it is significant because CREDO is almost certainly the telecom that challenged an NSL asking solely for subscriber information back in 2011; Judge Susan Illston ruled in their favor last March.

That may or may not say anything new about its challenge. I had considered whether this suggested it got some kind of bulk request (my new obsession). But the actual request in the NSL doesn’t leave much space for any bulk request.

The reference to what the government had required on page 11 of its reply to the government is redacted, and the reference to subscriber information on the following page lacks any pronoun to qualify it. Its language attesting to its preference to notice its subscriber uses “the,” which seems to suggest an entity rather than a person. A quotation from the FBI’s declaration on page 27 suggests the target is a plural noun.

But most of the rest of the discussion in the provider’s filings and the opinion suggest CREDO (if it is CREDO) challenged the NSL because it deemed the request on a CREDO subscriber to infringe on that subscriber’s First Amendment rights which are implicated in choosing CREDO (see pages 24-5), as well as CREDO’s ability to fight NSLs and PATRIOT more generally.

There’s two more related items of interest in CREDO’s Transparency Report. It includes two passages on related legislation — one mapping out things it can’t comment on, and one mapping out its stance on various pieces of legislation.

It is important to note that it may not be possible for CREDO or any telecom carrier to release to the public a full transparency report, as the USA PATRIOT Act and other statutes give law enforcement the ability to prevent companies from disclosing whether or not they have received certain orders, such as National Security Letters (NSLs) and Section 215 orders seeking customer information.

[snip]

CREDO supports the repeal the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 and the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, and the passage of Rep. Rush Holt’s Surveillance State Repeal Act. Until full repeal can be achieved, CREDO has worked specifically to reform the worst abuses of both acts. This includes fighting to roll back the National Security Letter (NSL) provisions of the USA PATRIOT Act, and fighting to make FISA Court opinions public so that the American people know how the secret FISA court is interpreting the law. CREDO endorses the USA Freedom Act and the Amash Amendment, both aimed at halting the indiscriminate dragnet sweeping up the phone records of Americans. CREDO also opposes Senator Feinstein’s FISA Improvements Act which would codify the NSA’s unconstitutional program of surveillance by bulk collection.

Note it points to USA PATRIOT that prevents it from fully responding because it would be gagged in the case of both NSLs and Section 215 orders. (It made me wonder whether the government went and got a Section 215 order after Illston’s ruling.)

Then it describes opposing both PATRIOT and the FISA Amendments Act, which highlights FAA’s absence from CREDO’s list of statutes that limit its ability to fully respond.

Most telecoms would also be subject to FAA orders (incidentally: did you know telecom orders have been going up since 2012?). But CREDO is apparently not, for this reason.

Customer information refers to non-content information such a customer’s name, address, bill information, or handset or account information. Regarding the content of customer communications, CREDO does not receive or store the content of customer communications. This report includes only CREDO’s requests and does not include requests that may have been directed to another carrier.

I assume that Sprint (from which CREDO leases access) retains all CREDO’s customers’ content. If that’s right (and given the reference to “requests that may have been directed to another carrier,”) I wonder if the FBI initially served Sprint for this customer information based off content already collected.

It’s one possibility, I guess (though that would obviously weaken CREDO’s case, if they made it, that the FBI was infringing on its customer’s First Amendment choice to work with CREDO).

In any case, there are a few interesting new tidbits. And just as importantly, CREDO’s catalog of the requests it did get does lay an excellent standard for Verizon’s upcoming report.