Jim Comey Makes Bogus Claims about Privacy Impact of Electronic Communications Trasaction Record Requests

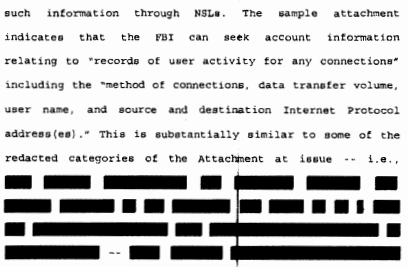

![]() On November 30, Nicholas Merrill was permitted to unseal the NSL he received back in 2004 for the first time. That request asked for:

On November 30, Nicholas Merrill was permitted to unseal the NSL he received back in 2004 for the first time. That request asked for:

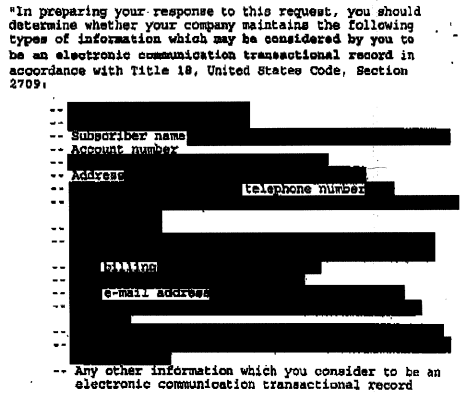

the names, addresses, lengths of service and electronic communication transaction records [ECTR], to include existing transaction/activity logs and all e-mail header information (not to include message content and/or subject fields) for [the target]

The unsealing of the NSL confirmed what has been public since 2010: that the FBI used to (and may still) demand ECTRs from Internet companies using NSLs.

On December 1, House Judiciary Committee held a hearing on a bill reforming ECPA that has over 300 co-sponsors in the House; on September 9, Senate Judiciary Committee had its own hearing, though some witnesses and members at it generally supported expanded access to stored records, as opposed to the new restrictions embraced by HJC.

Since then, a number of people are arguing FBI should be able to access ECTRs again, as they did in 2004, with no oversight. One of two changes to the version of Senator Tom Cotton’s surveillance bill introduced on December 2 over the version introduced on November 17 was the addition of ECTRs to NSLs (the other was making FAA permanent).

And yesterday, Chuck Grassley (who of course could shape any ECPA reform that went through SJC) invited Jim Comey to ask for ECTR authority to be added to NSLs.

Grassley: Are there any other tools that would help the FBI identify and monitor terrorists online? More specifically, can you explain what Electronic Communications Transactions Record [sic], or ECTR, I think that’s referred to, as acronym, are and how Congress accidentally limited the FBI’s ability to obtain them, with a, obtain them with a drafting error. Would fixing this problem be helpful for your counterterrorism investigations?

Comey: It’d be enormously helpful. There is essentially a typo in the law that was passed a number of years ago that requires us to get records, ordinary transaction records, that we can get in most contexts with a non-court order, because it doesn’t involve content of any kind, to go to the FISA Court to get a court order to get these records. Nobody intended that. Nobody that I’ve heard thinks that that’s necessary. It would save us a tremendous amount of work hours if we could fix that, without any compromise to anyone’s civil liberties or civil rights, everybody who has stared at this has said, “that’s actually a mistake, we should fix that.”

That’s actually an unmitigated load of bullshit on Comey’s part, and he should be ashamed to make these claims.

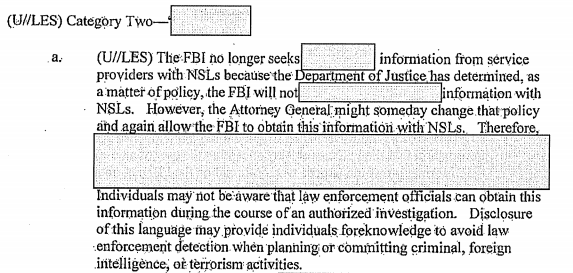

As a reminder, the “typo” at issue is not in fact a typo, but a 2008 interpretation from DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel, which judged that FBI could only get what the law said it could get with NSLs. After that happened — a DOJ IG Report laid out in detail last year — a number (but not all) tech companies started refusing to comply with NSLs requesting ECTRs, starting in 2009.

The decision of these [redacted] Internet companies to discontinue producing electronic communication transactional records in response to NSLs followed public release of a legal opinion issued by the Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) regarding the application of ECPA Section 2709 to various types of information. The FBI General Counsel sought guidance from the OLC on, among other things, whether the four types of information listed in subsection (b) of Section 2709 — the subscriber’s name, address, length of service, and local and long distance toll billing records — are exhaustive or merely illustrative of the information that the FBI may request in an NSL. In a November 2008 opinion, the OLC concluded that the records identified in Section 2709(b) constitute the exclusive list of records that may be obtained through an ECPA NSL.

Although the OLC opinion did not focus on electronic communication transaction records specifically, according to the FBI, [redacted] took a legal position based on the opinion that if the records identified in Section 2709(b) constitute the exclusive list of records that may be obtained through an ECPA NSL, then the FBI does not have the authority to compel the production of electronic communication transactional records because that term does not appear in subsection (b).

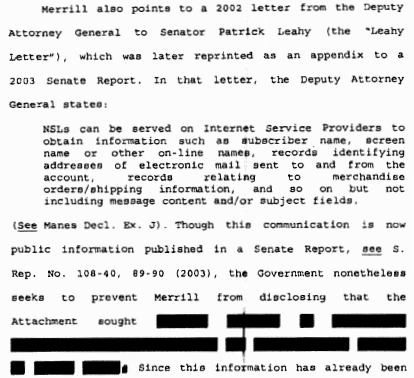

Even before that, in 2007, FBI had developed a new definition of what it could get using NSLs. Then, in 2010, the Administration proposed adding ECTRs to NSLs. Contrary to Comey’s claim, plenty of people objected to such an addition, as this 2010 Julian Sanchez column, which he could re-release today verbatim, makes clear.

They’re calling it a tweak — a “technical clarification” — but make no mistake: The Obama administration and the FBI’s demand that Congress approve a huge expansion of their authority to obtain the sensitive Internet records of American citizens without a judge’s approval is a brazen attack on civil liberties.

[snip]

Congress would be wise to specify in greater detail just what are the online equivalents of “toll billing records.” But a blanket power to demand “transactional information” without a court order would plainly expose a vast range of far more detailed and sensitive information than those old toll records ever provided.

Consider that the definition of “electronic communications service providers” doesn’t just include ISPs and phone companies like Verizon or Comcast. It covers a huge range of online services, from search engines and Webmail hosts like Google, to social-networking and dating sites like Facebook and Match.com to news and activism sites like RedState and Daily Kos to online vendors like Amazon and Ebay, and possibly even cafes like Starbucks that provide WiFi access to customers. And “transactional records” potentially covers a far broader range of data than logs of e-mail addresses or websites visited, arguably extending to highly granular records of the data packets sent and received by individual users.

As the Electronic Frontier Foundation has argued, such broad authority would not only raise enormous privacy concerns but have profound implications for First Amendment speech and association interests. Consider, for instance, the implications of a request for logs revealing every visitor to a political site such as Indymedia. The constitutionally protected right to anonymous speech would be gutted for all but the most technically savvy users if chat-forum participants and blog authors could be identified at the discretion of the FBI, without the involvement of a judge.

That legislative effort didn’t go anywhere, so instead (the IG report explained) FBI started to use Section 215 orders to obtain that data. That constituted a majority of 215 orders in 2010 and 2011 (and probably has since, creating the spike in numbers since that year, as noted in the table above).

Supervisors in the Operations Section of NSD, which submits Section 215 applications to the FISA Court, told us that the majority of Section 215 applications submitted to the FISA Court [redacted] in 2010 and [redacted] in 2011 — concerned requests for electronic communication transaction records.

The NSD supervisors told us that at first they intended the [3.5 lines redacted] They told us that when a legislative change no longer appeared imminent and [3 lines redacted] and by taking steps to better streamline the application process.

But the other reason Comey’s claim that getting this from NSL’s would not pose “any compromise to anyone’s civil liberties or civil rights” is bullshit is because the migration of ECTR requests to Section 215 orders also appears to have led the FISA Court to finally force FBI to do what the 2006 reauthorization of the PATRIOT Act required it do: minimize the data it obtains under 215 orders to protect Americans’ privacy.

By all appearances, the rubber-stamp FISC believed these ECTR requests represented a very significant compromise to people’s civil liberties and civil rights and so finally forced FBI to follow the law requiring them to minimize the data.

Which is probably what this apparently redoubled effort to let FBI obtain the online lives of Americans (remember, this must be US persons, otherwise the FBI could use PRISM to obtain the data) using secret requests that get no oversight: an attempt to bypass whatever minimization procedures — and the oversight that comes with it — the FISC imposed.

And remember: with the passage of USA Freedom Act, the FBI doesn’t have to wait to get these records (though they are probably prospective, just like the old phone dragnet was), they can obtain an emergency order and then fill out the paperwork after the fact.

For some reason — either the disclosure in Merrill’s suit that FBI believed they could do this (which has been public since 2010 or earlier), or the reality that ECPA will finally get reformed — the Intelligence Community is asserting the bogus claims they tried to make in 2010 again. Yet there’s even more evidence then there was then that FBI wants to conduct intrusive spying without real oversight.