31 Flavors of Stolen Classified Documents

In days ahead, there’ll be a heated discussion of what kind of sentence Espionage Act defendant Donald Trump might face. But even among the really experienced people — who correctly point out that Trump’s sentence would be a tiny fraction of the total 400 max he faces — I think the discussions are wrongly conceived. To explain why, I plan to return to my argument that the Mar-a-Lago indictment is tactical.

But first, I want to emphasize the magnitude of the fact DOJ charged Trump with hoarding 31 documents, each charged as an individual count and described, with classification markings, in the indictment. Virtually all of these documents are the type that the government is normally loathe to include at trial, and yet DOJ piled them on, compartmented document on top of compartmented document. The decision to commit to presenting all of them at trial is really remarkable, and must be (and is not being) accounted for in discussions of potential sentencing.

As background I’d like to review five similar prosecutions.

Daniel Hale

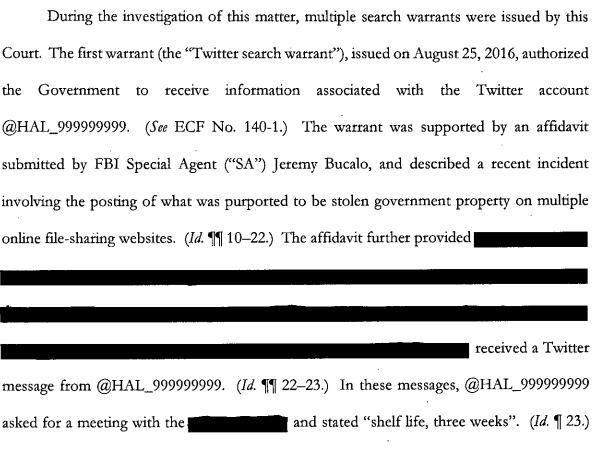

First consider two recent prosecutions (Chelsea Manning’s court martial, after which she was sentenced 35 years, is a third) where the indictments listed a long catalog of stolen documents like DOJ did with Trump: Hal Martin and Daniel Hale.

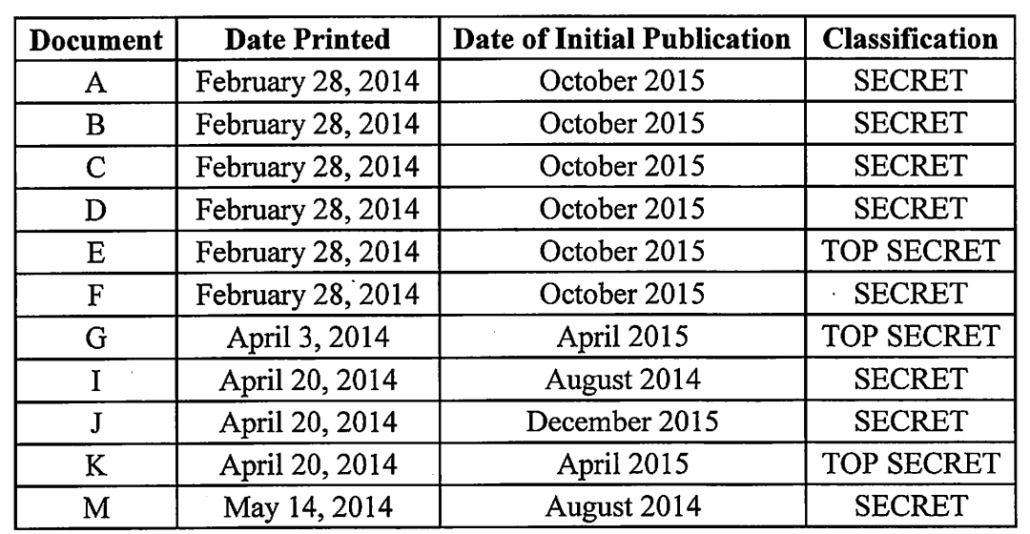

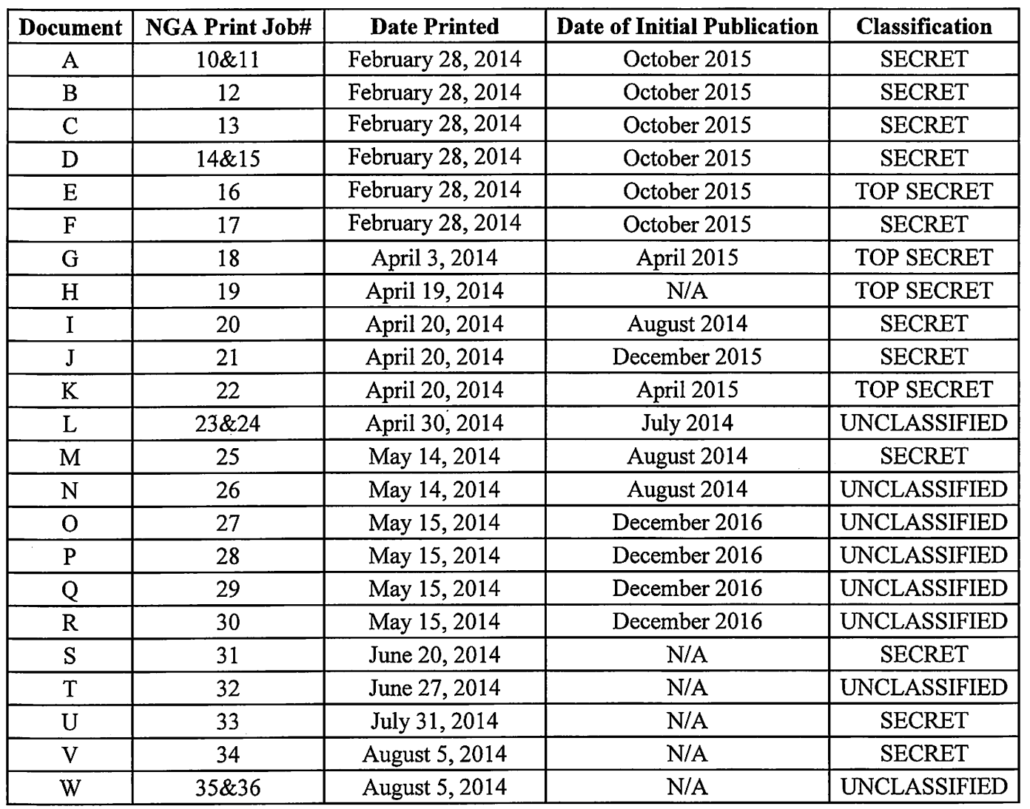

In Hale’s case, the indictment first listed all 23 documents he printed out from his job at a defense contractor, only four of which were as sensitive as most of the documents Trump was charged for hoarding.

DOJ only described the 11 documents that were published by The Intercept (document H, the fourth TS document, was not published by The Intercept and so not included in the charged documents). It then charged five counts:

- 18 USC 793(c) for taking the 11 documents ultimately published

- 18 USC 793(e) for taking and sharing the files with Jeremy Scahill

- 18 USC 793(e) for causing to be published the files

- 18 USC 798(a)(3) for sharing 4 SIGINT documents (documents A, D, E, and K, above)

- 18 USC 641 for taking the files, charged to include the 11 that got published and a few other unclassified documents that they had proof he had taken

Hale pled guilty to one count without a plea agreement immediately before trial and got a 45 month sentence. He is due to be released in July 2024.

Had Hale gone to trial, the government wouldn’t have had to expose any new information (though it would need to declassify it), because every charged document had been published already. So DOJ really risked very little by charging all 11 documents published by The Intercept. Any damage was already done.

Hal Martin

The way DOJ charged Hal Martin, though, is more akin to how DOJ has charged Trump.

Martin, remember, was arrested, guns-a-blazing, immediately after Shadow Brokers pegged him as the source of the documents being released in 2016. When the FBI searched his home, they found stacks and stacks of documents, including in his car. It took six months to charge Martin, presumably because DOJ had to do an investigation into what and why he had taken — including whether he was Shadow Brokers or had wilfully leaked the documents to Shadow Brokers. Unlike Trump, he was in pre-trial custody that whole time.

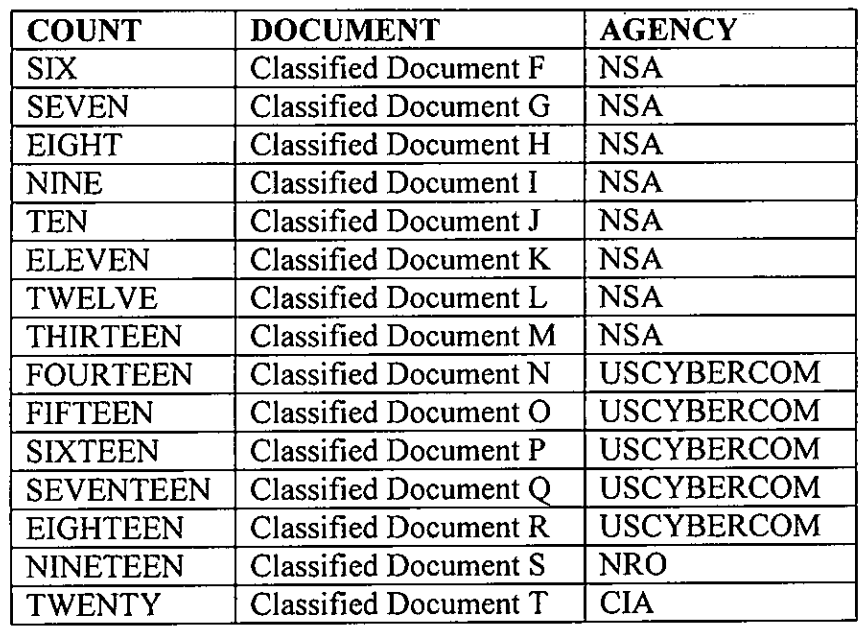

In the end, there were no dissemination charges (ultimately, the public record in his case is inconclusive whether he wilfully leaked these documents or not, but if he did, DOJ either couldn’t prove it or chose not to try). As DOJ did with Trump, each of a bunch of documents, a total of 20, were charged as separate counts.

There are descriptions of each of these 20 documents in the indictment, but not classification markers. The indictment describes that they were a mix of Secret, Top Secret, and SCI.

DOJ presumably got sign-off from the agencies to present these documents at trial, but after a very long pre-trial process, Martin ultimately pled guilty in March 2019 to one count of 18 USC 793(e) as part of a plea agreement, with an agreed on sentence of 9 years, one year short of the 10-year max. He’s scheduled for release in May 2024.

Nghia Pho

By comparison, Nghia Pho — the other presumed source of Shadow Brokers, from whom hackers stole a bunch of NSA files loaded onto his home computer — entered into a plea agreement from the start. His Information didn’t describe any of the documents he took home, though suggested many were TS/SCI. Pho was sentenced to 66 months. Pho, who was in his 60s when he was sentenced and is now 72, is due for release in September.

This is the way DOJ normally prefers to treat those responsible for leaks and other compromises, because the prosecution does little additional damage. Of course, there was never a chance in hell such an approach would work for Trump.

Note that Thomas Windom, who is one of the lead January 6 prosecutors, was on the Pho prosecution team.

Jeremy Brown

Two other relevant cases involve Floridians prosecuted in the last year. With Oath Keeper Jeremy Brown, the government did list and present the five documents, all classified Secret, he was accused of hoarding. They used the Silent Witness rule to present the classified documents at trial, all of which were far more dated and less sensitive than the ones Trump is accused of stealing. Here’s how they described that process in the pre-trial process.

First, the government would provide each juror, the Court, and the defense with a binder of unredacted copies of the Classified Documents. The same process was followed in Mallory, 40 F.4th at 173, and it would enable the jurors to examine the Classified Documents while the government elicits unclassified testimony about the same from its expert witness. As in Mallory, the defense would be permitted to follow the same procedures during cross examination and/or with its own cleared expert, should the defense choose to retain one. Id. This procedure ensures that the jury has full access to the information it needs to fulfill its obligations. Id. at 178 (“But a review of the record reveals that the silent witness rule denied the jury none of the information on which Mallory based his defense.” (emphasis in original)). Second, the government will have Bates and line numbers added to the Classified Documents to enable the witness, the government, and the defense to direct the jurors to specific portions of the material.

Brown was only convicted of one of five Espionage Act counts, but nevertheless was sentenced to 87 months for the document as well as the illegal weapons he was convicted of hoarding.

Robert Birchum

Finally, there’s Robert Birchum, a retired Lieutenant Colonel who was just sentenced to 36 months a few weeks ago. Birchum was found hoarding over 300 documents he had collected before 2008, in 2017, six years ago. The Air Force declined to court martial him, and he was honorably discharged (it sounds like the Air Force really valued the counterinsurgency work he did). The first his case was made public was in January, when he was charged by Information with one count of 793(e). That Information did describe two documents he was charged with:

two documents classified at the TOP SECRET/SCI level from the National Security Agency (NSA) relating to the national defense that discuss the NSA’s capabilities and methods of collection of information.

The government asked for a bottom of guidelines sentence of 78 months, emphasizing Birchum’s abuse of a position of trust and the sensitivity of the documents he took. Among other things Birchum raised at sentencing is that he was so important to the Air Force, they sent him back to Afghanistan even after diagnosing him with PTSD. He also invoked all the high ranking people, including Trump, who had brought classified records home.

Among others, Mr. Birchum’s case now shares a stage with the current President of the United States, the former President and Vice-President of the United States, and a former Secretary of State. Looking a bit further back in time, one can see examples of other high-level government executives involved in the same type of offenses, including a former national security adviser who pled guilty to knowingly removing classified documents from the National Archives and a former CIA director and retired four-star general who pled guilty to sharing classified documents with his biographer and mistress. Both the former national security adviser and the former CIA director were sentenced to pay a fine and probation. No charges have been bought against any of the other individuals noted above. Similar cases involving lower-level government employees that did result in prison sentences typically involved attempts to obstruct the investigation or actual dissemination of the information or both.

He was sentenced to 36 months.

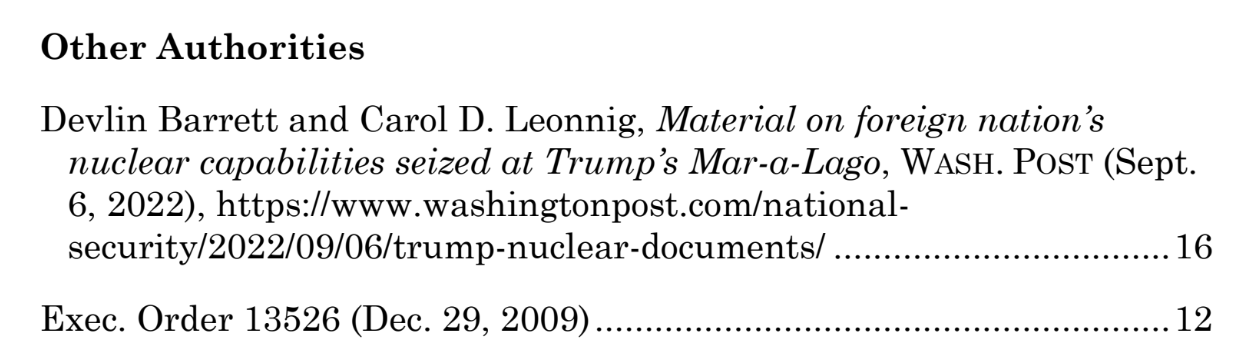

The reason I laid all this out is to suggest how remarkable it was that DOJ listed 31 documents Trump allegedly stole. Of the cases above, they did so with less sensitive, dated records that Brown was charged with, with the 11 documents already published in Hale’s case, and then the catalog of documents charged against Martin, some of which may also have been compromised as part of the Shadow Brokers release. If Martin’s charged documents were already compromised as part of the Shadow Brokers case, it means that among these cases, there is no precedent for the government choosing to charge a catalog of incredibly sensitive documents like they have with Trump.

That’s one reason I keep harping on the footnote in a DOJ filing in the Trump case from last September, invoking the Pho case (where we know the documents were badly compromised) to suggest that sometimes the Intelligence Community has to operate on the assumption that programs have been compromised and shut them down.

Once the government loses positive control over classified material, the government must often treat the material as compromised and take remedial actions as dictated by the particular circumstances. Depending on the type and volume of compromised classified material, such reactions can be costly, time consuming and cause a shift in or abandonment of programs. In this case, the fact that such a tremendous volume of highly classified, sophisticated collection tools was removed from secure space and left unprotected, especially in digital form on devices connected to the Internet, left the NSA with no choice but to abandon certain important initiatives, at great economic and operational cost.

We know one of the 31 documents charged against Trump — the document described in Count 8 that fell out of a box in the storage closet — would be treated as compromised, particularly if someone knocked the box over or is believed to have found it (remember that there are no cameras inside the storage room).

I can’t emphasize this point enough: One possible explanation for the catalog of charges against Trump is that the IC knows, or made a decision last September to assume, that all of these documents have been compromised. It’s one of the most likely ways to explain DOJ’s willingness to include all of them in charges, just like they did with the documents charged against Hale.

That possibility is not being factored into any of the discussions about sentencing, and it should be. The IC likely has to assume that the many intelligence services that targeted Mar-a-Lago, including two known Chinese infiltrators, found some of these documents, or maybe just the musicians and partygoers who could have had access while they were taking a shit.

Importantly, all the documents charged remained in an unsecured storage room after it became public that there were classified documents among the ones that Trump had delivered to NARA in January 2022. (Note, among the really sensitive documents that weren’t included in Trump’s charges are ones classified HCS-O, describing HUMINT operations.)

The Pho and Birchum examples show that DOJ would far prefer negotiating a plea agreement in advance, to minimize further damage to national security. But Trump made quite clear after the search last year, he was unwilling to go quietly.

The only one of these five who went to trial was Brown, and DOJ used the Silent Witness rule for him. That rule is rightly controversial even with disfavored shithole defendants like Brown (or Kevin Mallory, who was convicted of spying for China using it). I simply can’t imagine using the Silent Witness rule in a trial with a former President. The issues of legitimacy are too great. And so, if this thing goes to trial, I assume redacted copies of all these documents would be introduced as evidence that would get shared with the public.

Which is why I point to the Martin case as the one most similar to Trump. My read of that case is that DOJ charged so many documents — just 20, though, rather than 31 — as part of the coercion process to get Martin to plead.

The problem, in Donald Trump’s case, is that he has more incentive to start a civil war than plead guilty to these charges.

Those are some of the assumptions — not to mention that by charging this in West Palm Beach, where Aileen Cannon was likely to and did get the assignment — that Jack Smith must have had in mind when he charged the MAL case like he did.

With every other similarly situated defendant, DOJ has pursued strategies to get the defendant to plead before exacerbating the damage of the compromise at trial. But with Donald Trump, they’re facing a uniquely intransigent defendant. And that is what Jack Smith was facing when he decided to charge this case this way.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)