The Future of Work Part 1: John Maynard Keynes

As the global depression spiraled towards its depths in 1930, John Maynard Keynes wrote a cheerful article on the future of work: Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. He argued that it wouldn’t be too long before capital accumulation and technological change would come near to solving the economic problem of material subsistence, of producing enough goods and services to provide everyone with the necessities of life and largely relieving them of the burden of work.

The paper begins with a very brief description of the problems of the time:

We are suffering, not from the rheumatics of old age, but from the growing-pains of over-rapid changes, from the painfulness of readjustment between one economic period and another. The increase of technical efficiency has been taking place faster than we can deal with the problem of labour absorption; the improvement in the standard of life has been a little too quick; the banking and monetary system of the world has been preventing the rate of interest from falling as fast as equilibrium requires.

This statement anticipates the views of Karl Polanyi in The Great Transformation, and of Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism. They argue persuasively that massive technological changes led to changes in social structures which were profoundly upsetting to large numbers of people. Polanyi says that a decent society would take steps to relieve people of these stresses, perhaps by forcing a slower pace of change, or perhaps by legislation to protect the masses. Arendt claims that for a while, imperialism offered a solution by absorbing some of the excess workers. Both believed that the stresses of constant change and displacement of workers played an important role in the rise of fascism.

Keynes then points out the history of growth in world output. From the earliest time of which we have records, he says, to the early 1700s, there was little or no change in the standard of life of the average man. There were periods of increase and decrease, but the average was well under .5%, and never more than 1% in any period. The things available at the end of that period are not much different from those available at the beginning. He argues that growth began to accelerate when capital began to accumulate, around 1700.

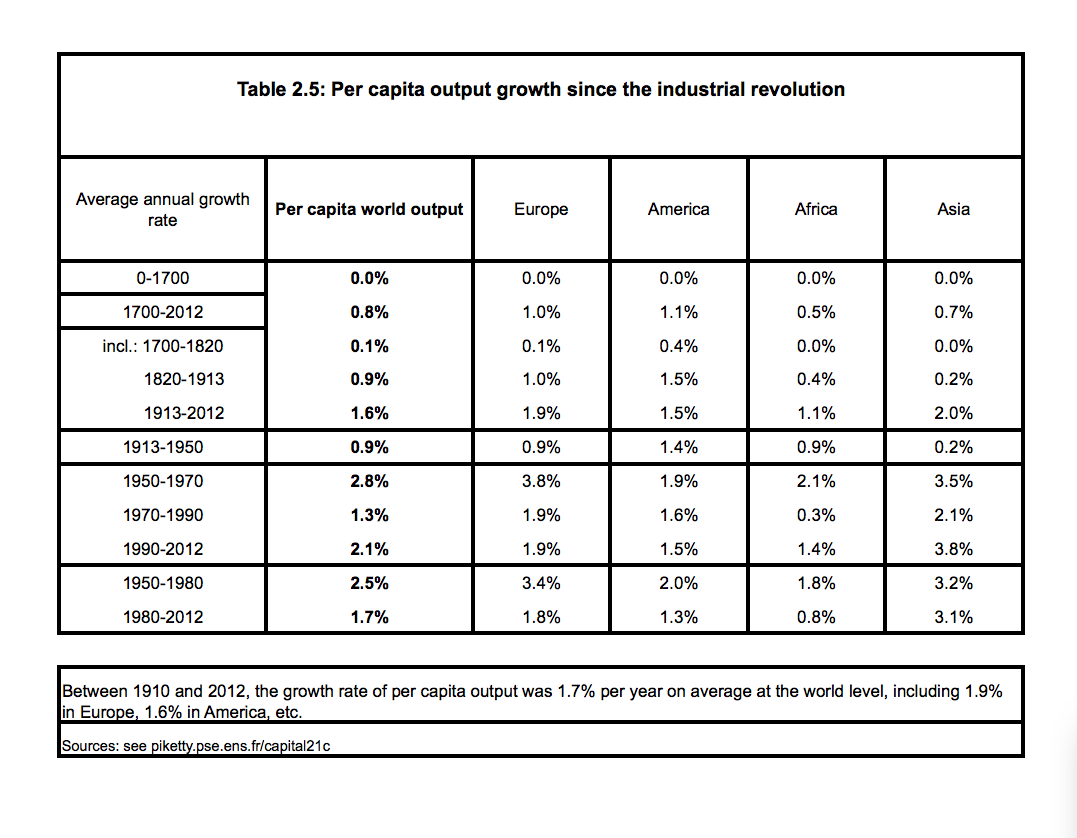

It’s interesting to note that this sketch of economic history accords nicely with that provided by Thomas Piketty in Capital In The Twenty-First Century. This is Piketty’s Table 2.5. Compare this with Figure 2.4, The growth rate of world per capita output since Antiquity until 2100.

Keynes argues that since 1700 there has been a great improvement in the lives of most people, and there is every reason to think that will continue. Certainly there was the then current problem of technological unemployment, with technology displacing people faster than the it was creating new jobs. But he says it is reasonable to think that in 100 years, by 2030, people will be 8 times better off, absent war and other factors. He says there are two kinds of needs, those that are absolute, and those with the sole function of making us feel superior to others. The latter may be insatiable, he says, but the former aren’t, and we are getting closer to satisfying them. In so doing, we are getting close to solving the ancient economic problem: the struggle for subsistence.

That problem is indeed ancient. It shows up in Genesis, 3:17. Adam and Eve have eaten the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, and the Almighty punishes Adam with these words:

To Adam he said, “Because you listened to your wife and ate fruit from the tree about which I commanded you, ‘You must not eat from it,’ “Cursed is the ground because of you; through painful toil you will eat food from it all the days of your life.

To be relieved of this ancient curse should be a wonderful thing. Keynes doesn’t think it will be an easy transition though. The struggle for subsistence is replaced by a new problem: how to use the new freedom, how to use the new-found leisure. He thinks people will have to have some work, at least at first, to give us time as a species to learn to enjoy leisure. He thinks that those driven to make tons of money will be seen once again in moral terms: as committing the sin of Avarice. They will be ignored or controlled in the interests of the rest of us.

As it turns out, this wasn’t one of Keynes’ better predictions. It isn’t clear that there is such a thing as a minimum absolute needs, for example, and technology has not yet removed the need for all work. Still, the goal of solving the economic problem seems sensible, and his discussion of the problems of a possible transition seems accurate.

People want to work, and they want everyone else to work too. There have been a number of reported interviews with Trump voters, many of who claim that this has become a give-away society. People complain that it pays better to be out of work than in work because of all the free stuff you get, health care (Medicare), free phones, food stamps, SSDI, free housing and so on, so they voted for Trump thinking he’d fix it so that only the deserving poor would get that free stuff. They think people don’t want to work, which feels like projection, and if they have to work, everyone should. Work has a number of social benefits, including a sense of purpose, responsibility, and pride. How are these to be handled in Keynes’ Eden?

The pace of technological change has picked up. It not only affects blue-collar workers, it’s starting to hit on doctors, lawyers and even translators. Here’s an article on improvements in translation based on neural network machine learning from the New York Times Magazine; and here’s a report from the White House on the impact of artificial intelligence on jobs. And here’s an article in the NYT’s Upshot column discussing the White House Report, and a rebuttal from Dean Baker.

These problems are crucial to the future of democracy. They concern the nature of our institutions and our social structures, as well as questions about our nature as human beings. I’ll take these up in more detail in future posts in this series.

Update: Here’s a link to the Keynes paper discussed in this post.