What Happened To The Cultural Elites: The Capitalist Celebration

Posts in this series

What Happened To The Cultural Elites: Changes In The Conditions of Production

David Swartz says that Pierre Bourdieu thought that the economic elites know the importance of cultural power. Culture and Power: The Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu, p. 127, 220. Cultural capital provides a justification for their exercise of economic power; it legitimizes the economic elites. Economic elites also found it valuable for their children to acquire cultural power through educational credentials and acquisition of the skills needed to manage businesses and fortunes. Bourdieu thinks that the cultural elites and the economic elites compete for power in society. In the US in the 1950s, the economic elites and the cultural elites reached a Truce. See this post for more detail and a discussion of the breakdown of the Truce.

The form of the Truce was that the cultural elites would dominate the discussion of what we now call social issues and the economic elites would dominate management of the economy. Before the Truce, the cultural elites included Marxists, Communists, socialists, and others who seriously questioned or even denied the legitimacy of the exercise of power by the economic elites. These groups were purged from the cultural elites, partly because of McCarthyism and partly by individual changes of mind. The Democratic party also dumped those groups. Republicans accepted many of the premises of liberalism, making a contested liberalism the dominant ideology. C. Wright Mills saw this Truce.

He challenged what he called the “Great Celebration” among liberal intellectuals who praised the return of prosperity and the rise of the nation to global superpower status.

The Great Celebration is a nice way to describe the Truce. The terms of the Truce required the cultural elites to accept capitalism as the one true economic faith. That had a number of bad results.

1. Conventional wisdom says that the Democratic Party is the party of the working class and the middle class. This connection is based on a political policy of shared prosperity. As neoliberalism rose to dominance, this policy was shed in favor of a market-based allocation of prosperity, with the economic elites controlling the way the market handled that allocation. When the Democrats capitulated to this policy, they broke the link between the working and middle classes and the cultural elites, a point commenter Lefty665 raised.

As I read Swartz, Bourdieu questioned why the cultural elites felt connected to the working class at all. Their habitus is completely different from that of the working class, and much more like that of the bourgeoisie especially in tastes and education. Bourideu suggests several reasons, including the fact that the working class and the cultural elites are in dominated positions in their segments of society, but that seems like resentment, and it seems weak.

I think the more likely explanation as to why cultural elites feel an affinity to the working and middle classes is a sense of fairness, of equity, and even a deep faith in the idea that all people are created equal and are entitled to equal dignity. Marxism may offer a framework for understanding the role of the proletariat in society, but there are others that don’t rely on historical materialism, for example the ideas of John Rawls in A Theory of Justice. In any event, it may be a better question to ask why so many of the cultural elites at least claim a connection to the working class.

Regardless of why, once the economic link is broken, the cultural elites have no base of support in society. Their incomes depend on their continued employment in the systems described in the first post in this series. That dependence undercuts their independence, even their intellectual autonomy. The claim to represent the interests of the working and middle classes became hollow.

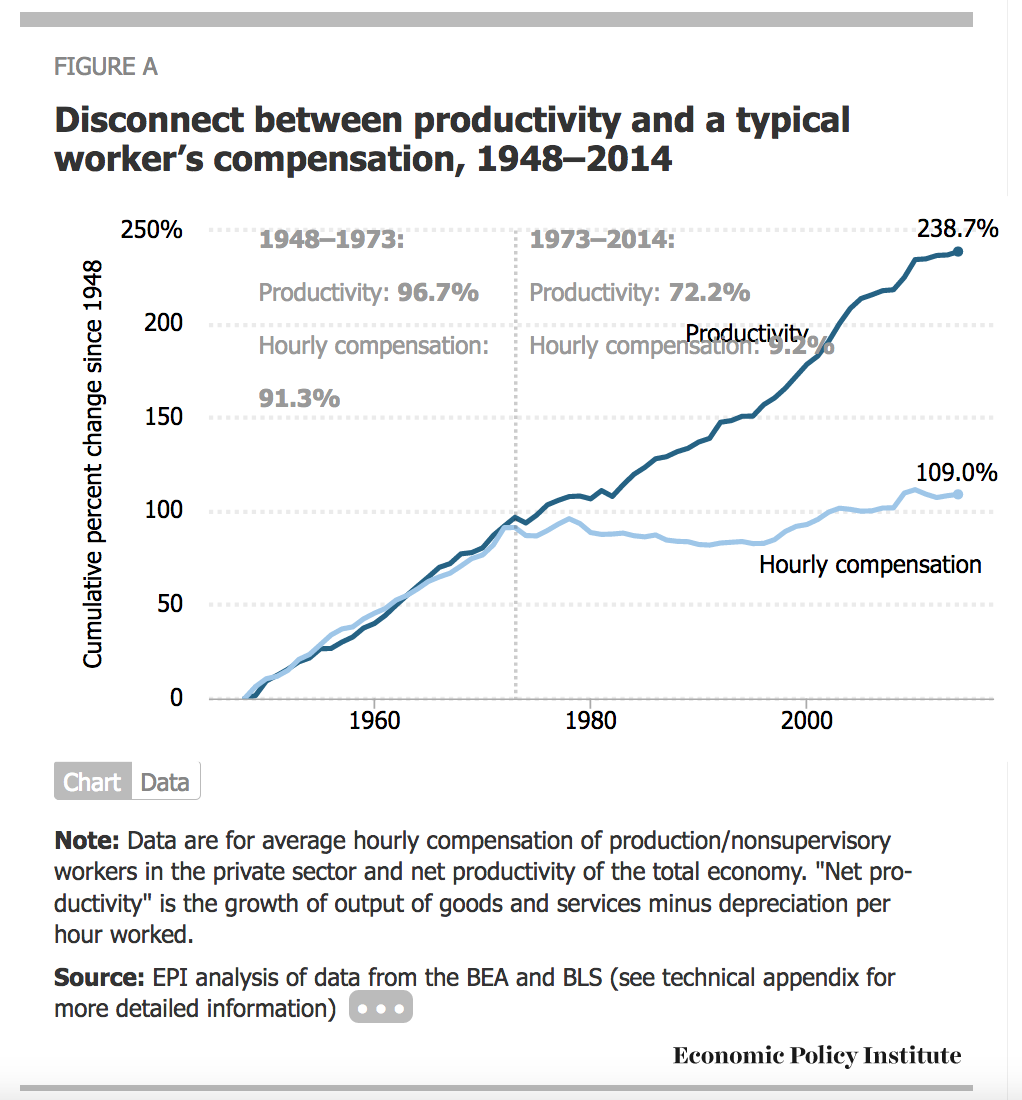

2. Joining the Great Celebration required cultural elites to stop the study and advocacy of alternatives to capitalism, especially Marxism, but also socialism. Then the cultural elites slowly lost interest in the entire area of economics, and did not generate new alternatives or better ways to operate a capitalist system. As a result, neoliberal economists became the dominant force in the field of economics. When financial crises arose, the solutions considered mostly tracked the views of neoliberal economists. Later crashes were dealt with on neoliberal terms: government help for the financial sector, more free markets, less regulation and an abandonment of the reforms of the 1930s.

When the Great Crash came, there was no alternative. A short burst of Keynesian stimulus was followed by the usual neoliberal remedies, this time including austerity, privatization efforts (charter schools, Obamacare), and more emphasis on deregulated markets. Also, none of the economic elites were punished , and neither were neoliberal economists, because, after all, it was merely capitalist greed and some exuberant animal spirits, nothing malicious, let alone criminal. Millions of people were hammered, especially the working and middle classes, who lost an enormous part of their wealth while the economic elites were bailed out. The Democrats did not even recognize any of this as a problem largely because they had no alternatives to neoliberalism. That was the fault of the Cultural Elites.

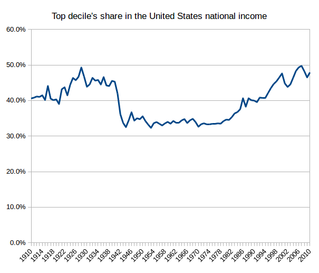

3. The acceptance of capitalist economics meant that social issues connected to the economy were ignored, especially the effects of wealth inequality and income inequality, and the dangers of concentration of market power through consolidation and the crushing of small businesses. Liberal economists claimed to be interested in the problems of wealth and income inequality, but did nothing about it, either in their work or in their public statements. Paul Krugman wrote at least one paper on rising inequality in the late 1990s, but there was no follow-up in the economics community. Krugman offered this explanation:

The other [issue one might model] involves the personal distribution of income and wealth. Why are investment bankers paid so much? Why did the gap between CEOs and the average worker widen so much after 1980?

And here’s the thing: we really don’t know how to model personal income distribution — at best we have some semi-plausible ad hoc stories.

Krugman says he agrees with this article by Justin Fox. Fox describes the explanation of a sociologist, Dan Hirschman, who argues that the study of inequality dried up because no one was interested. Hirschman says it wasn’t a “deliberate suppression of knowledge”, it was “normative ignorance.” Fox tries to justify this as normal because there are limited resources and so on.

The plain fact is that although inequality is a central issue in politics and economic life, economists didn’t study it. Neither Krugman nor Fox gets to the root of the problem: why didn’t economists think this was an important problem? After all, making a living and accumulating wealth are the most important economic issues for every single member of society, and they know that politics matters. So why weren’t there dozens of competing models working off tons of data? I can’t think of an explanation that doesn’t make economists as a group complicit in the basic neoliberal program of transferring wealth and power to the economic elites. Ignoring motive, I’d say the most plausible explanation has to do with the Great Celebration, and the shift away from criticizing capitalism.

There were gains from the Truce, but these are ugly consequences.

![[Photo: Annie Spratt via Unsplash]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Books_AnnieSpratt-Unsplash_mod1.jpg)