What If the US Had Fought the Saudis Instead of the Taliban?

Poof.

Our twenty year occupation of Afghanistan is ending in humiliating fashion. Jim and I are thinking about re-running every one of his posts cataloging the failures of training Afghans who would — and now have — changed sides when necessary or convenient.

While I’ve got burning questions about how Trump and his hand-picked Acting Secretary of Defense, Christopher Miller, made this defeat more certain, I’m going to hold off on recriminations for a bit. After all, we have two decades of accountability to demand.

I am, however, interested in how the way in which we’re fleeing Afghanistan will influence how President Biden responds to a demand from the families of the 9/11 victims to declassify more intelligence from the investigation. They have said Biden is not welcome at the memorial if he does not respond to their demand.

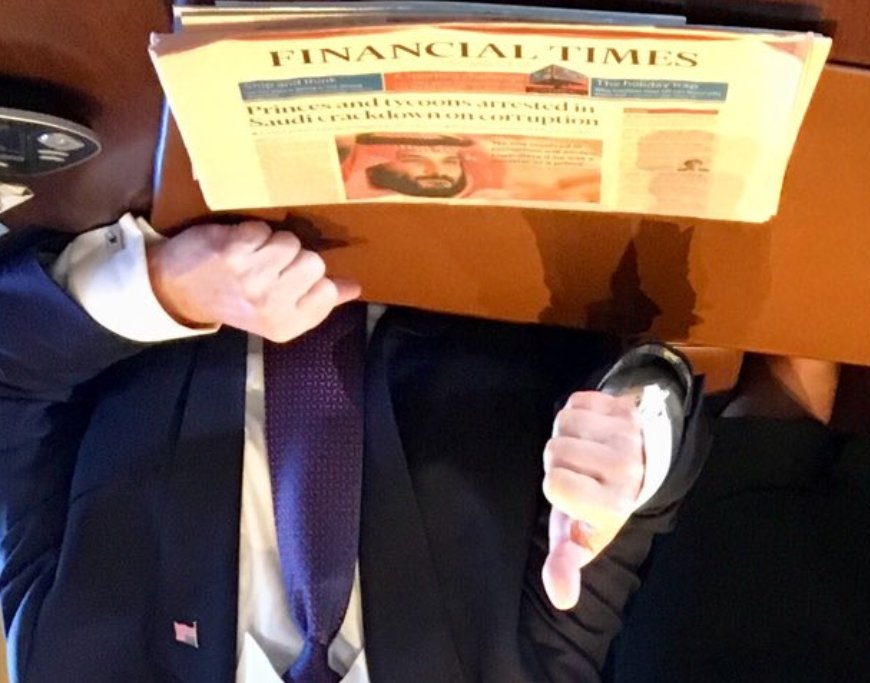

Families of 9/11 victims say an FBI offer to release some documents from its investigation into the attack has not gone far enough, and are demanding a comprehensive declassification review of all relevant material, particularly on Saudi Arabia’s role.

The FBI offer on Monday followed a call by some victims’ families and first responders for Joe Biden to stay away from ceremonies marking the 20th anniversary of the attack next month, if the president failed to honour a campaign pledge to lift the secrecy surrounding the multi-agency investigations.

The families want information on who financed and supported the attacks, and are currently suing the Saudi Arabian government in a federal court in New York. As part of that case, three former Saudi officials were questioned in June by the plaintiffs’ lawyers about their links with two of the 9/11 hijackers, Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi, who spent several months in southern California before the attack. Their testimony cannot be shared with the families under secrecy rules.

Of course, if Biden does respond fully, it will demonstrate that, rather than occupying Afghanistan for two decades, we should have been fighting the Saudis.

And yet, we remained allies with the Saudis, continuing to let Saudis like Ahmed Mohammed al-Shamrani enter the US without adequate vetting, allowing yet another Saudi-linked terrorist attack on US soil.

We have hidden the role that our “allies” the Saudis had in 9/11 for two decades because if we actually held them accountable, rather than inflicting our need for revenge on the Taliban, their oil could no longer be a cornerstone to our empire.

We could not hold the Saudis accountable because if we did, we would have had to stop burning oil.

We would have had to replace Saudi oil with renewables, a more modest way of life, and some humility.

We would have, out of necessity, done something about climate change.

We have plenty of time for recriminations about our failures in Afghanistan. But we have no time left to make up for the twenty years we might have spent addressing climate change instead.