John Durham’s Blind Man’s Bluff on DNS Visibility

On September 16, 2021, John Durham indicted Michael Sussmann on a single count of lying to the FBI, just days before the statute of limitations for that crime expired. Durham accused Sussmann of lying to hide that he had a client or clients on whose behalf he was sharing allegations about DNS anomalies involving Trump Organization and Alfa Bank.

Durham adopts the “DNC fabrication” theory from agents who badly screwed up the original investigation

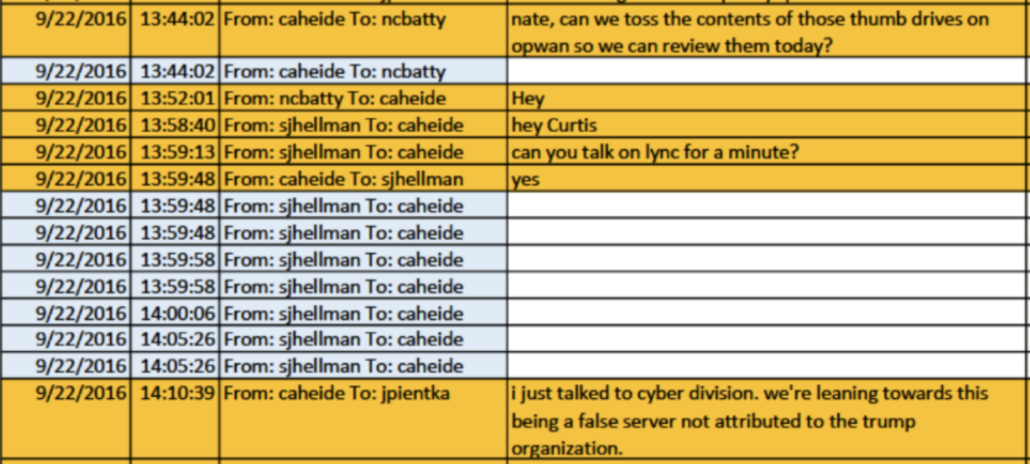

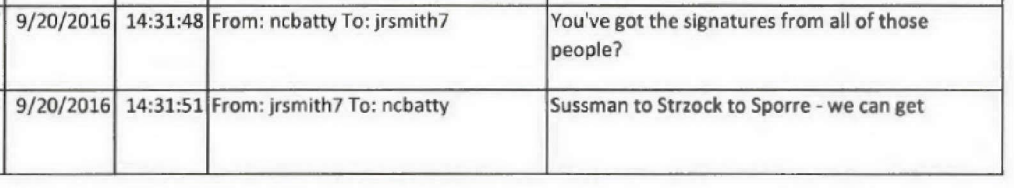

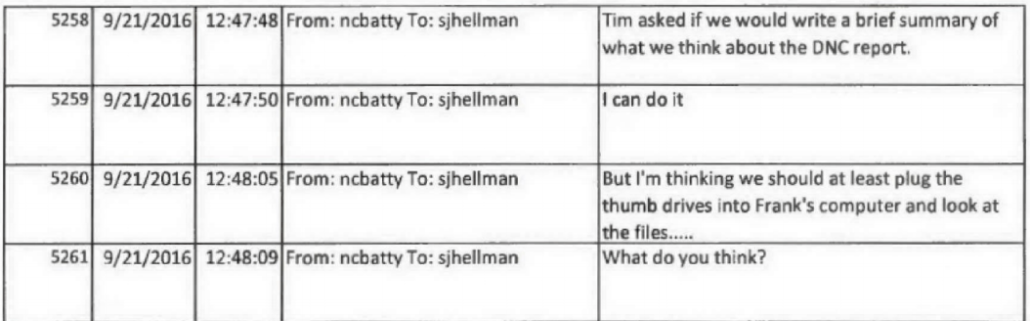

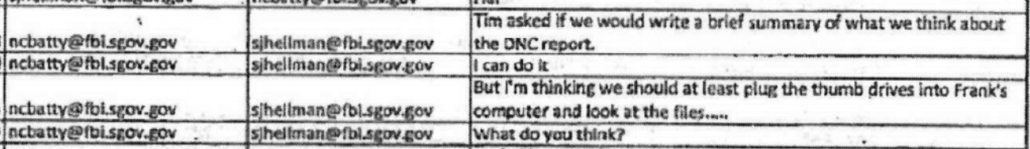

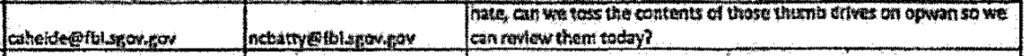

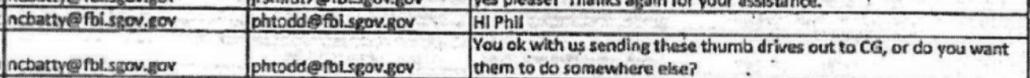

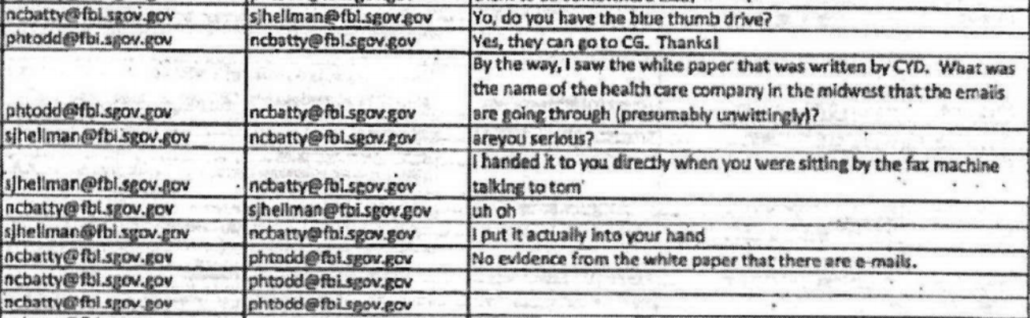

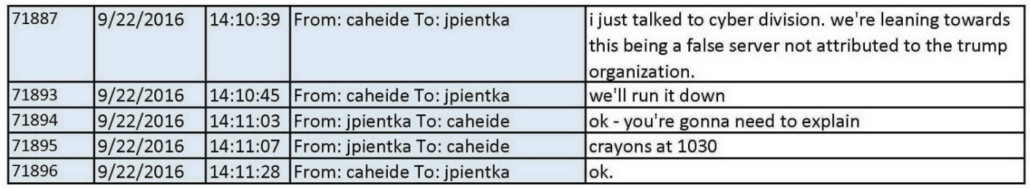

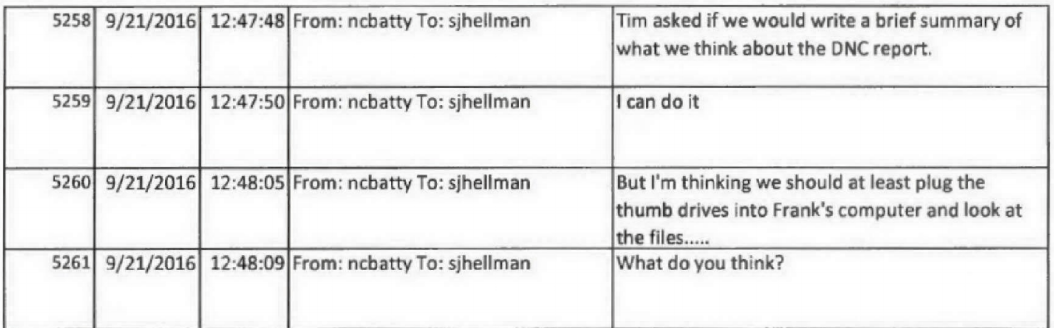

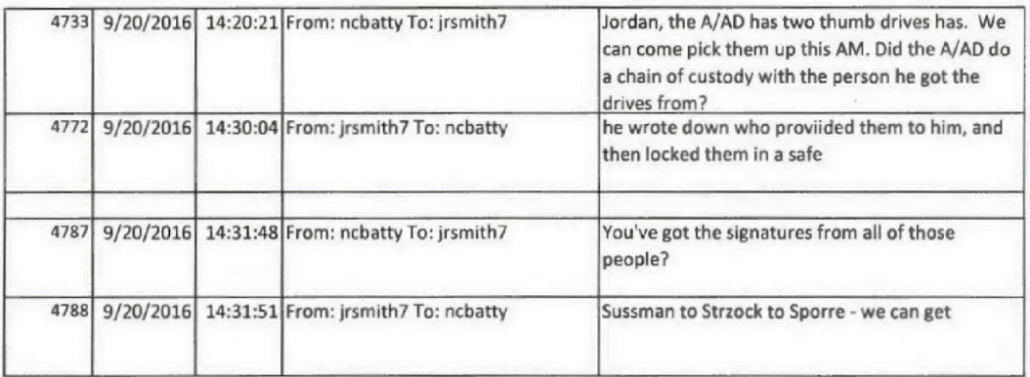

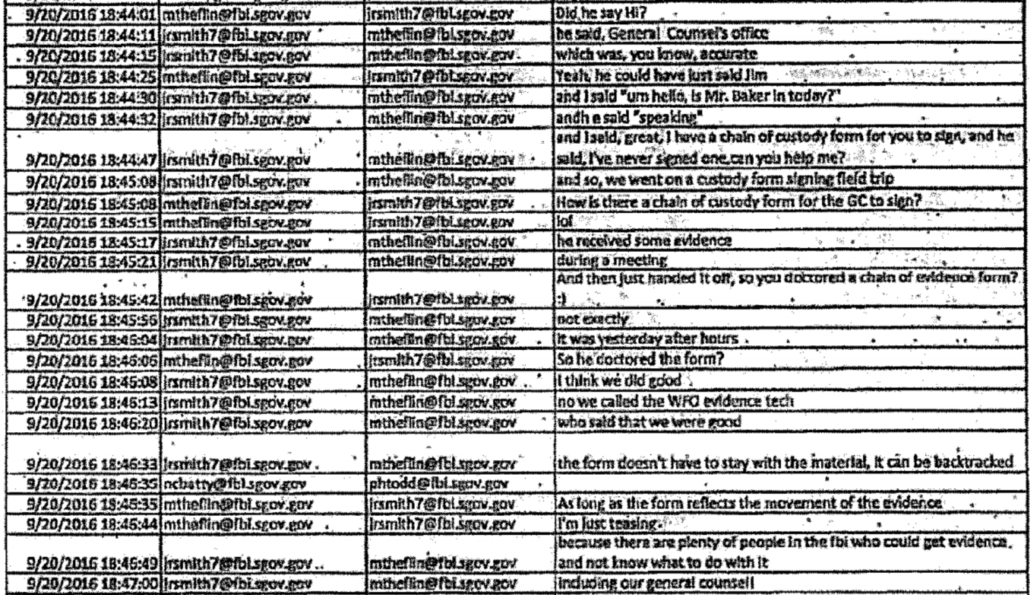

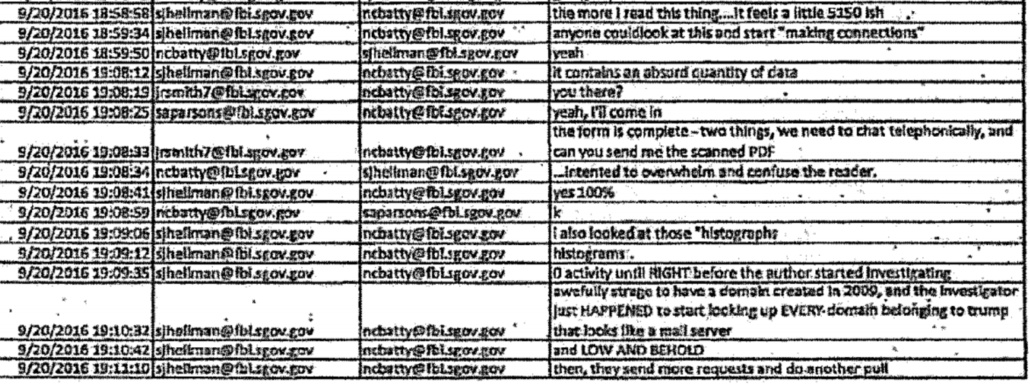

As I laid out here, the indictment adopted the “DNC fabrication” theory, the “fabrication” part of which was initially espoused in a hasty review by FBI Cyber agents Nate Batty and Scott Hellman by September 21, 2016, just two days after Sussmann shared a white paper describing anomalies involving Alfa Bank.

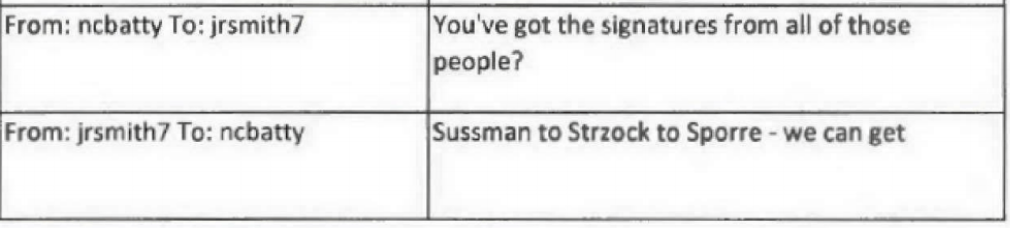

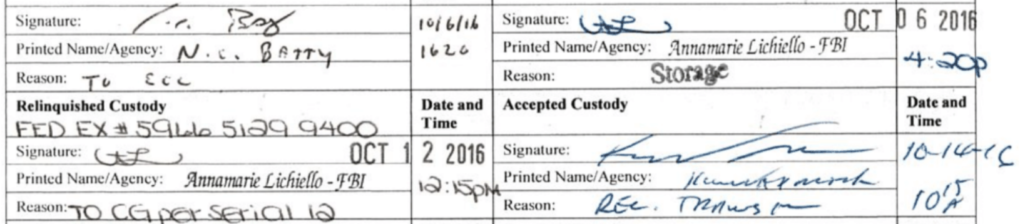

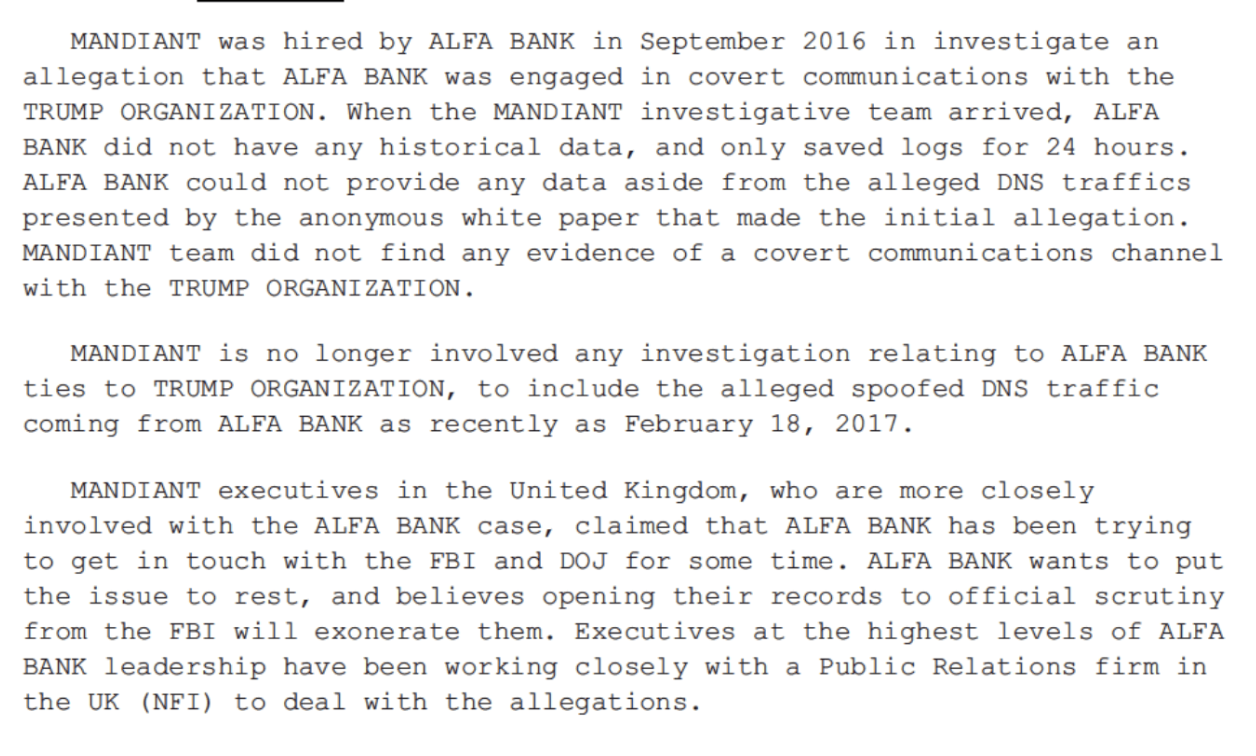

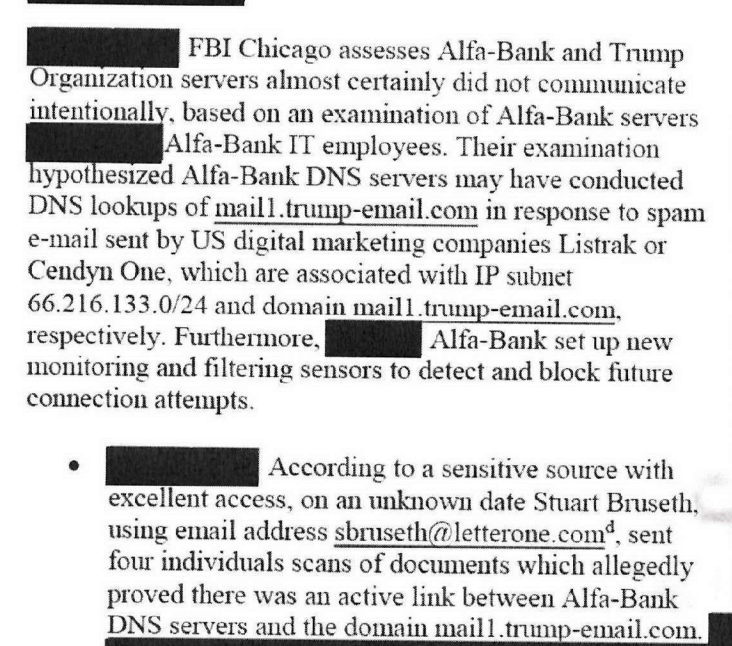

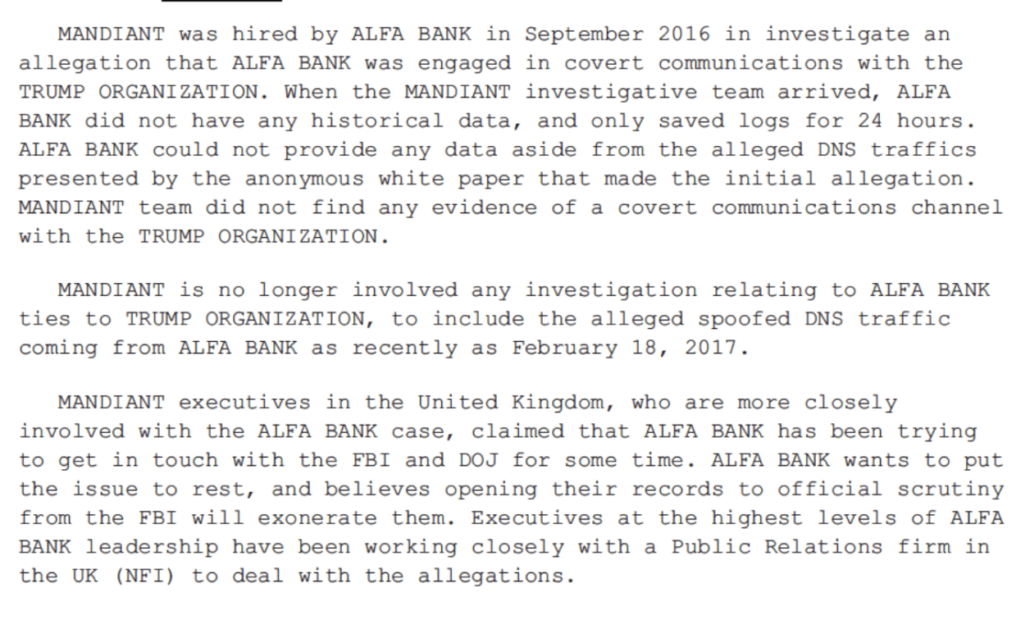

Durham adopted that theory in spite of proof, in their own summary, that the FBI agents had not closely reviewed the DNS logs included with the allegations, if they ever reviewed them at all. Durham adopted that theory in spite of irregularities in the chain of custody surrounding the handling of a Blue Thumb Drive that reportedly included DNS logs that were never reviewed. Durham adopted that theory in spite of the fact that Batty’s own Lync messages materially conflicted with a claim he made to Durham two years earlier: Batty claimed he had been refused information about the role of Sussmann in the allegations, when in fact his Lync messages showed he had been informed about Sussmann’s role from the start. Durham adopted that theory in spite of the fact that FBI started debunking parts of the “fabrication” story within hours of Batty and Hellman proposing it. Durham adopted that theory in spite of the fact that FBI’s own overt steps (during a pre-election period) and Alfa Bank’s curious lack of DNS logs made pursuing the allegations impossible.

That indictment was an insanely reckless thing for John Durham to do, building as it did on the investigative failures of Batty and Hellman, not to mention Batty’s own materially inconsistent claim.

Several things made that indictment even more reckless.

Durham fails to take basic investigative steps before indicting

First, in spite of the fact that Durham had already been investigating for 28 months by that point — Durham had already been investigating for six months longer than the entire Mueller investigation — there were a whole bunch of obvious investigative steps he had not yet taken. Between the indictment and the May 2022 trial, Durham would do the following:

- Interview the senior Hillary people with whom Durham had already criminally accused Sussmann of coordinating

- Obtain records from Sussmann’s coordination with the FBI in the wake of the DNC hack, which debunked some of Durham’s coordination claims, explained others, and made it clear a number of the people Durham claimed didn’t know Sussmann’s DNC ties had interacted with him in that context

- Pull FBI records showing that Sussmann helped to kill a NYT story the Hillary campaign badly wanted to run, effectively corroborating Sussmann’s explanation for sharing the anomalies

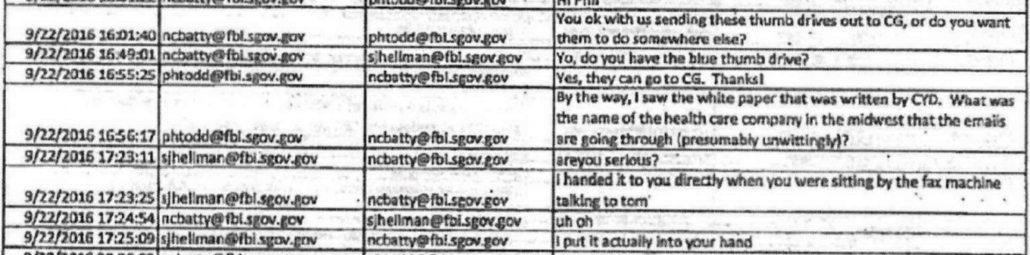

- Ask DOJ IG for the evidence they had obtained during their own years-long investigation, which revealed notes from a March 6, 2017 meeting taken by Tashina Gaushar, Mary McCord, and Scott Schools that showed the FBI understood Sussmann had a client

- Ask DOJ IG for a Jim Baker phone Durham had been told about years earlier but forgot to ask for; the phone extraction would show Baker’s calendar for the day of his meeting with Sussmann conflicted with his reconstructed memories about the day

- Ask Jim Baker to check his iCloud for texts with Sussmann which revealed further communications corroborating Sussmann’s explanation, but also showed that Durham indicted the wrong date for the crime of which he accused Sussmann

- Obtain notes from a former CIA officer showing that Sussmann told him he had a client

- Obtain records showing how valuable the FBI had found past assistance from Rodney Joffe

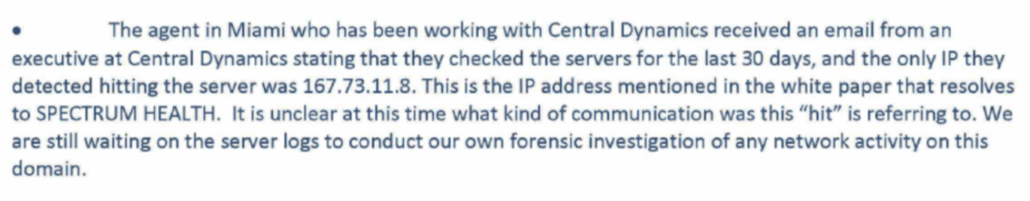

Durham also revealed two other interviews he only conducted after charging Sussmann: one with someone identified as Listrak Employee-1 and other unidentified personnel on October 27, 2021 and another with the CEO and CTO of Cendyn on November 17, 2021. As described, their interviews pertained exclusively to email, not DNS, and Durham doesn’t appear to have asked Cendyn about the contacts via its Metron messaging product done for some other client with Alfa Bank in the same time period, nor about the contact that did exist between Cendyn and the affected Spectrum IP address. It also doesn’t mention that Listrak reported no emails to Alfa Bank, one of the Bank’s evolving explanations for the anomalies, and any mail to Spectrum was sent elsewhere.

In his report, Durham makes no mention of whether he interviewed anyone at Spectrum Health or Alfa Bank, though a DC judge would observe that it was almost like the Sussmann indictment and an Alfa Bank lawsuit, “were written by the same people in some way.” There were large gaps involved with both entities in the original investigation and it’s not clear Durham made any effort to close them.

Durham accused the FBI of skipping investigative steps on Crossfire Hurricane that might have discovered exculpatory evidence, but none of that comes close to the many investigative steps he had not yet pursued in the 28 months he had already been investigating before indicting Sussmann.

Durham’s indictment of Sussmann piled his own investigative failures on top of those by Batty and Hellman.

Durham discovers his DNC fabrication theory involves real data

More problematic than Durham’s investigative incompetence, though, the Special Counsel charged Michael Sussmann on September 16, 2021, in spite of the fact that a month earlier, by mid-August, 2021, Durham’s team learned that the data Rodney Joffe and others used to conduct their research was absolutely real. The nature of how this came about remains obscure, but in addition to debunking the most simplistic “DNC fabrication” theories, the discovery made it impossible for Durham to continue to rely on the expert his team had been using. The discovery that the data that Batty and Hellman had dismissed in just one day was real should have led Durham to reconsider everything about his case.

Instead, Durham barreled forward with his indictment.

Durham invites the guy who screwed up the investigation to be his expert

Instead of reassessing his case, Durham responded to losing his expert by proposing that Hellman serve as the replacement, even though by Hellman’s own admission he only knows the basics about DNS.

DeFilippis. How familiar or unfamiliar are you with what is known as DNS or Domain Name System data?

A. I know the basics about DNS.

[snip]

Berkowitz. And then, more recently, you met with Mr. DeFilippis and I think Johnny Algor, who is also at the table there, who’s an Assistant U.S. Attorney. Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. They wanted to talk to you about whether you might be able to act as an expert in this case about DNS data?

A. Correct.

Q. You said, while you had some superficial knowledge, you didn’t necessarily feel qualified to be an expert in this case, correct, on DNS data?

A. On DNS data, that’s correct.

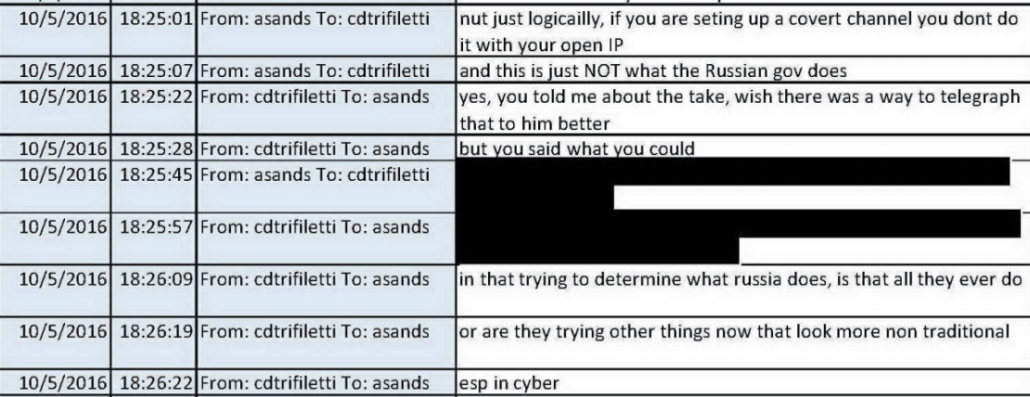

Hellman was one of just two people, aside from John Durham himself, who had a stake in sustaining the “DNC fabrication” theory he had floated before closely reviewing the evidence. That Durham even considered making him his expert is a testament that Durham was interested in protecting his “DNC fabrication” theory, not interested in expertise, much less what the actual evidence said.

Durham includes two expert reviews unmoored from any prosecutorial decision

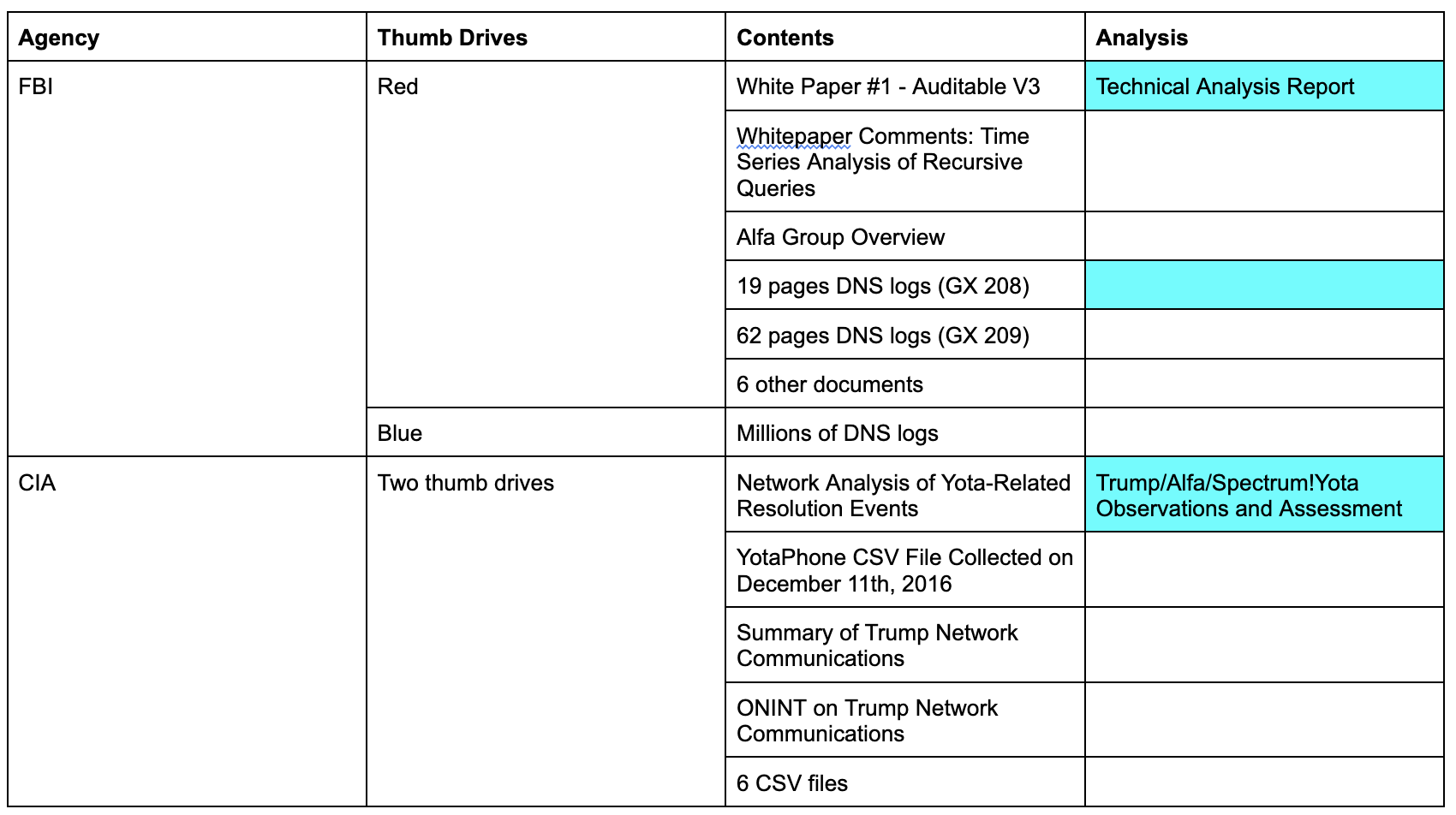

And that’s why Durham’s inclusion of two expert reviews of the allegations Sussmann shared with the government is of interest:

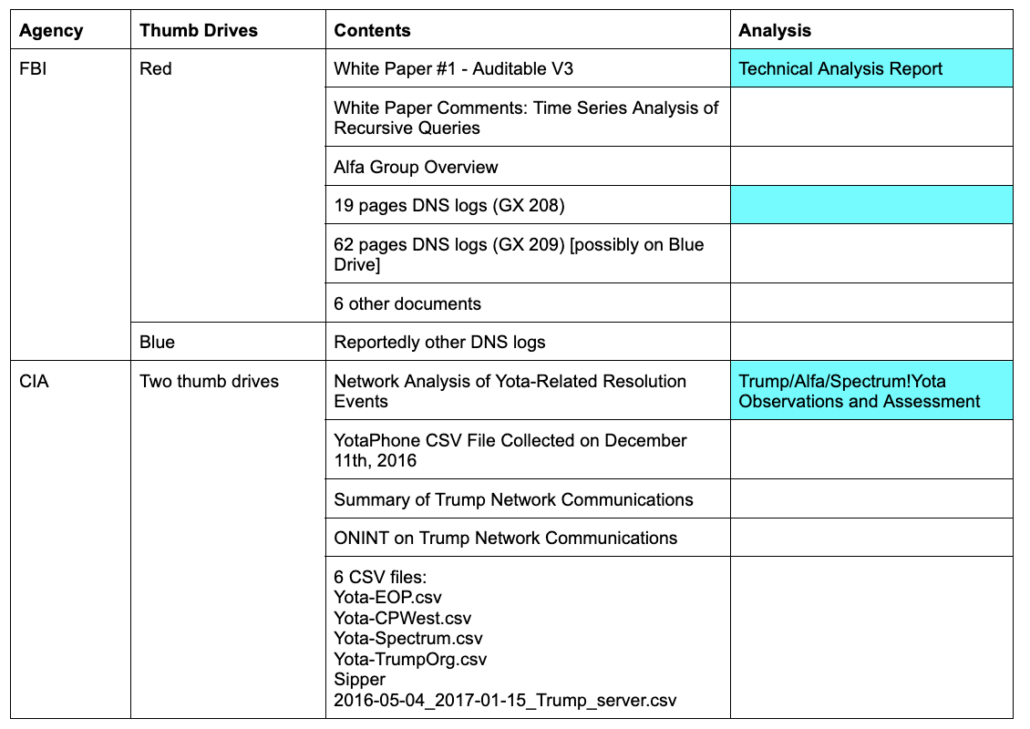

- 1671 FBI Cyber Technical Operations Unit, Trump/Alfa/Spectrum/Yota Observations and Assessment (undated; unpaginated).

- 1635 FBI Cyber Division Cyber Technical Analysis Unit, Technical Analysis Report (April 20, 2022) (hereinafter “FBI Technical Analysis Report”) (SCO _ 094755)

With one exception, Durham describes those reviews in a 13-page section of his report that purports to be about the ongoing efforts by Rodney Joffe and others to chase down the Alfa Bank anomalies and some unusual traffic probably reflecting the presence of Yota Phones in the US. The section itself has no place in a prosecutorial memo, because the only interaction with the government described in that section involved a Georgia Tech researcher refusing HPSCI’s request to help chase down these allegations. The rest involves Joffe continuing to chase this issue with his own data, which insofar as it demonstrates Joffe’s sustained concern about this, independent of any election, undermines pretty much all of Durham’s conspiracy theories. The declination decision regarding fraud — which Andrew DeFilippis used to claim that Joffe was still a subject of the investigation more than five years after the events in question, thereby keeping him off the stand in Sussmann’s trial — didn’t even mention Joffe.

But the description of these reviews in this section really doesn’t have a place where Durham put it, because along with the Cendyn and Listrak interviews, one of the reviews appears to have been last minute prep for the Sussmann trial and the other played a key role in an affirmatively misleading court filing that led Trump to make death threats against Sussmann.

These reviews in Durham’s report supported his last-ditch effort to cement the belief that Hillary framed Donald Trump. They’re here to prove, once and for all, that Sussmann was wrong.

Here’s how Durham introduces his efforts to redo the work Batty and Hellman and others botched so many years ago:

This subsection first describes what our investigation found with respect to the allegation that there was a covert communications channel between the Trump Organization and Alfa Bank. It includes the information we obtained from interviews of Listrak and Cendyn employees. It then turns to the allegation that there was an unusual Russian phone operating on the Trump Organization networks and in the Executive Office of the President. We tasked subject matter experts from the FBI’s Cyber Technical Analysis and Operations Section to evaluate both of these allegations.

But as with so much else in this report, they don’t do what they claim to. Durham ensured his experts sustained the blindness that Batty and Hellman willfully adopted so many years ago to avoid concluding that the allegations might be real.

As I noted here, the two reviews purport to review the Alfa Bank allegations — shared with both the FBI and (in updated form) the CIA — and the YotaPhone allegations shared with the CIA. In one place, Durham claims “the same FBI experts” did both reviews, though he attributes them to different groups. But that’s important because if they are the same experts, then they should know of both reviews.

Durham incites death threats because Joffe investigated Barack Obama

The YotaPhone review must have been done first because, as I noted above and show below, the analysis matches claims Durham made in a filing purporting to raise conflicts but mostly airing allegations for which the statute of limitations had just expired. Here’s how Durham describes the allegations in the report:

Specifically, Sussmann provided the CIA with an updated version of the Alfa Bank allegations and a new set of allegations that supposedly demonstrated that Trump or his associates were using, in the vicinity of the White House and other locations, one or more telephones from the Russian mobile telephone provider Yotaphone. The Office’s investigation revealed that these additional allegations relied, in part, on the DNS traffic data that Joffe and others had assembled pertaining to the Trump Tower, Trump’s New York City apartment building, the EOP,1558 and Spectrum Health. Sussmann provided data to the CIA that he said reflected suspicious DNS lookups by these entities of domains affiliated with Yotaphone.1559 Sussmann further stated that these lookups demonstrated that Trump or his associates were using a Yotaphone in the vicinity of the White House and other locations.1560

Durham’s description of these allegations relies on redacted sections of two trial exhibits (but not a related one that shows Sussmann was not hiding having a client). Because the section of these trial exhibits was redacted, it’s not clear whether Durham is representing how these CIA witnesses described Sussmann’s claims fairly. That’s important because — as we’ll see — Durham misrepresents the YotaPhone white paper.

As Durham described, Sussmann provided four documents and 6 data files to the CIA.

During the meeting, Sussmann provided two thumb drives and four paper documents that, according to Sussmann, supported the allegations. 1564

1564 The titles of the four documents were: (i) “Network Analysis of Yota-Related Resolution Events”; (ii) ·’YotaPhone CSV File Collected on December 11th, 2016″; (iii) “Summary of Trump Network Communications”; and (iv) “ONINT [sic] on Trump Network Communications.” The two thumb drives contained six Comma Separated Value (“.CSV”) files containing IP addresses, domain names and date/time stamps.

Unlike the Red and Blue Thumb Drive, Durham makes clear that his experts actually examined these thumb drives.

Here are three of the documents:

- Network Analysis of Yota-Related Resolution Events

- Summary of Trump Network Communications

- OSINT on Trump Network Communications

I understand the csv files include:

- yota-eop

- yota-cpwest

- yota-spectrum

- yota-trumporg

- sipper

- 2016-05-04_2017-01-15_Trump_server.csv

I’ll say more about them below.

Durham’s description of the analysis, titled, “Trump/Alfa/Spectrum/Yota Observations and Assessment,” generally obscures whether it is rebutting a claim (redacted in the trial exhibits) made by Sussmann (“the presentation”) or included in the white paper and data (“the above-quoted white papers about the Yotaphone allegations” and “Yotaphone-related materials”) provided, and he doesn’t repeat or address the Alfa Bank side of these observations (which have no tie to the YotaPhone claims).

But the technical analysis does not, at all, debunk the YotaPhone observations.

The FBI DNS experts with whom we worked also identified certain data and information that cast doubt upon several assertions, inferences, and allegations contained in (i) the above-quoted white papers about the Yotaphone allegations, and (ii) the presentation and Yotaphone-related materials that Sussmann provided to the CIA in 2017. In particular:

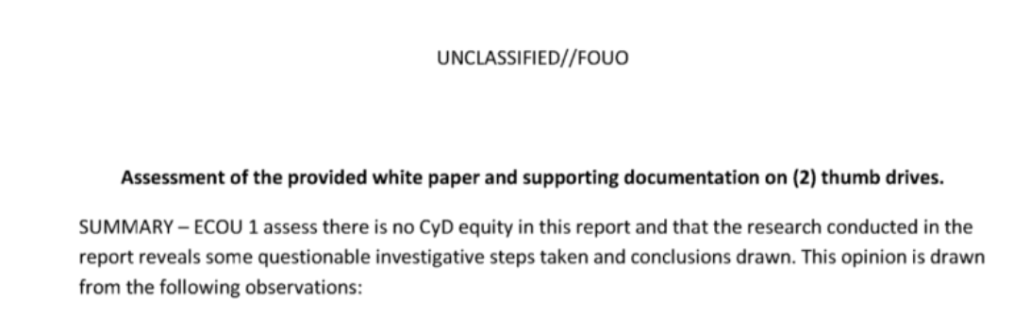

- Data files obtained from Tech Company-2, a cyber-security research company, as part of the Office’s investigation reflect DNS queries run by Tech Company-2 personnel in 2016, 2017, or later reflect that Yotaphone lookups were far from rare in the United States, and were not unique to, or disproportionately prevalent on, Trump-related networks. Particularly, within the data produced by Tech Company-2, queries from the United States IP addresses accounted for approximately 46% of all yota.ru queries. Queries from Russia accounted for 20%, and queries from Trump-associated IP addresses accounted for less than 0.01 %.

- Data files obtained from Tech Company-1, Tech Company-2, and University-1 reflect that Yotaphone-related lookups involving IP addresses assigned to the EOP began long before November or December 2016 and therefore seriously undermine the inference set forth in the white paper that such lookups likely reflected the presence of a Trump transition-team member who was using a Yotaphone in the EOP. In particular, this data reflects that approximately 371 such lookups involving Yotaphone domains and EOP IP addresses occurred prior to the 2016 election and, in at least one instance, as early as October 24, 2014. [bold and italics mine]

Compare that to the supposed debunking from the gratuitous conflicts filing that led to death threats.

The Indictment further details that on February 9, 2017, the defendant provided an updated set of allegations – including the Russian Bank-1 data and additional allegations relating to Trump – to a second agency of the U.S. government (“Agency-2”). The Government’s evidence at trial will establish that these additional allegations relied, in part, on the purported DNS traffic that Tech Executive-1 and others had assembled pertaining to Trump Tower, Donald Trump’s New York City apartment building, the EOP, and the aforementioned healthcare provider. In his meeting with Agency-2, the defendant provided data which he claimed reflected purportedly suspicious DNS lookups by these entities of internet protocol (“IP”) addresses affiliated with a Russian mobile phone provider (“Russian Phone Provider-1”). The defendant further claimed that these lookups demonstrated that Trump and/or his associates were using supposedly rare, Russian-made wireless phones in the vicinity of the White House and other locations. The Special Counsel’s Office has identified no support for these allegations. Indeed, more complete DNS data that the Special Counsel’s Office obtained from a company that assisted Tech Executive-1 in assembling these allegations reflects that such DNS lookups were far from rare in the United States. For example, the more complete data that Tech Executive-1 and his associates gathered – but did not provide to Agency-2 – reflected that between approximately 2014 and 2017, there were a total of more than 3 million lookups of Russian Phone-Provider-1 IP addresses that originated with U.S.-based IP addresses. Fewer than 1,000 of these lookups originated with IP addresses affiliated with Trump Tower. In addition, the more complete data assembled by Tech Executive-1 and his associates reflected that DNS lookups involving the EOP and Russian Phone Provider-1 began at least as early 2014 (i.e., during the Obama administration and years before Trump took office) – another fact which the allegations omitted. [bold mine]

The bolded narrative shows these are the same report. If 3 million is 46% of the total of around 6.521 million lookups globally, then 1,000 Trump-related queries would be .01% of the global total.

But it is an innumerate stat. I’m not the FBI, and definitely not a top FBI cyber expert. But even my humble little blog occasionally relies on William Ockham to explain things that should be bloody obvious to the Federal government, such as that 3 million DNS requests amount to one family’s worth of use.

Contra Durham, 3 million DNS requests for a related IP addresses over a four-year period means these requests are very rare.

For comparison purposes, my best estimate is that my family (7 users, 14 devices) generated roughly 2.9 million DNS requests just from checking our email during the same time frame. That’s not even counting DNS requests for normal web browsing.

If you’re going to make a federal case out of this, at least make some attempt to understand the topic.

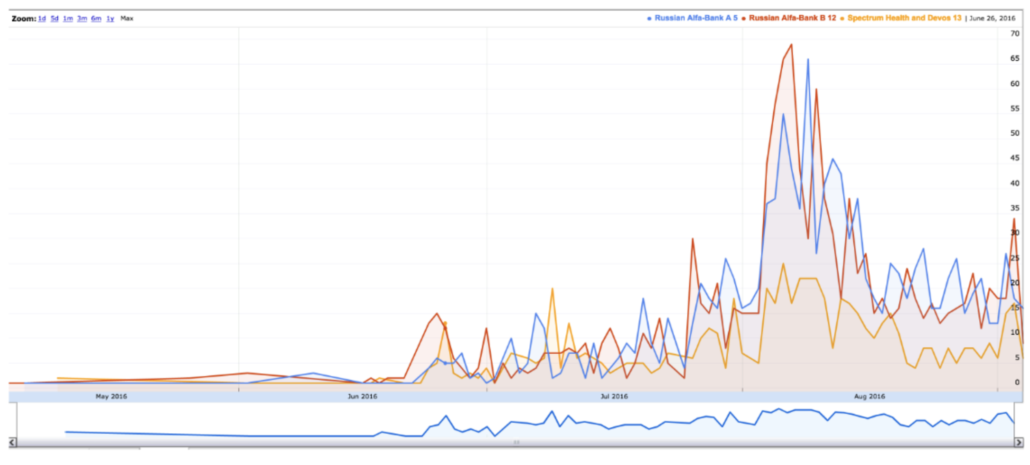

Durham and his hand-picked experts in the FBI suggest that because, among the very rare number of global requests, almost half appear in the US, it means they aren’t rare. From that, Durham and his experts argue that the fact that Trump’s properties (and Spectrum and the Executive Office of the President) are part of this tiny club is not cause for concern.

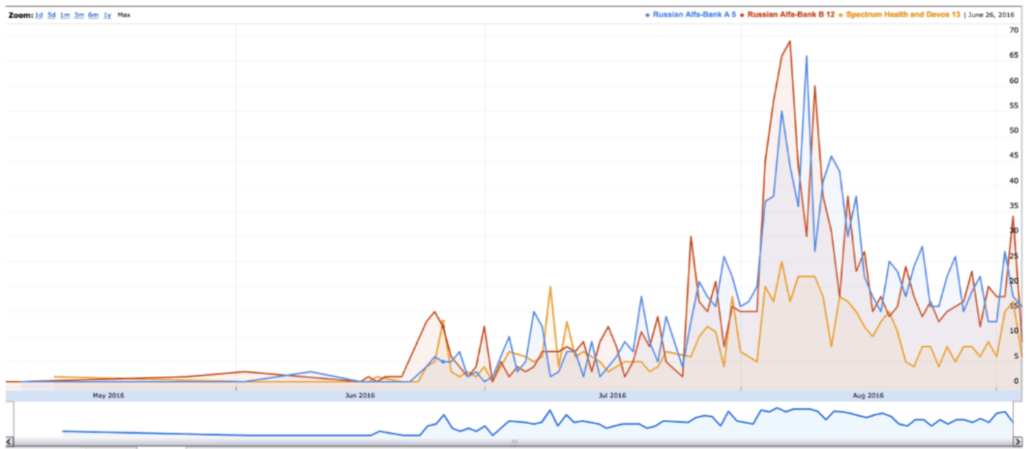

They’re doing so even though among the domains included in the CSV tables is wimax-client-yota-ru, which shows up in Wordfence’s IOC lists for the GRU attack on the election. Durham and his FBI experts are arguing that it is not alarming that there would be several look-ups to such a domain in October 2016 from the Executive Office of the President, periodical look-ups to that domain from Trump Organization starting in August 2016, and persistent such look-ups from the suspect Spectrum IP address starting in November 2016.

And about those EOP look-ups. Durham claims, in the italicized language above, that there is an, “inference set forth in the white paper that such lookups likely reflected the presence of a Trump transition-team member who was using a Yotaphone in the EOP.” Sussmann may have said that. But it’s not in the white paper. In fact, there’s just one reference to the EOP in the white paper at all, and it’s not included in the speculative paragraph that there may be a tie between the Spectrum traffic and the Trump traffic.

Network traffic analysis strongly suggests communications between Russian networks and Trump Tower, associated Trump properties, with artifacts also present at EOP. Spectrum Health resolver IP 167.73.110.8 in Grand Rapids MI is also observed making similar queries.

The traffic data indicates: (a) There are Russian-made cellular devices on these networks, seldom seen elsewhere in the US; and (b) these networks appear to be at- tempting SIP-connections to Russian networks which very few IPs globally are seen trying to resolve.

It is possible that one or more devices is at times travelling between locations as there are sometimes gaps possibly correlated to newsworthy events such as New York NY to Grand Rapids MI, lifting of some sanctions on Russia, and the disappearance of the queries from New York in mid December and from Grand Rapids MI in mid January 2017.

In other words, as he did when he invented an allegation against Hillary that the Russians didn’t even make, he’s inventing an inference here, the kinds of inferences he tried to criminalize when Joffe did them. Further, he suggests that Sussmann and Joffe didn’t reveal that the lookups started before the election, even though the CSV data included shows lookups starting on October 2, 2016, which last I checked was before the election.

Durham, who admits in his report that these lookups inexplicably ended before Inauguration, nevertheless falsely insinuated in a court filing that Sussmann and Joffe had based their claims on lookups that post-date Trump’s inauguration. Durham is debunking Durham now! And that false claim from Durham led Trump to suggest that because Joffe found an IOC associated with the people who hacked the election within EOP, Sussmann should be put to death.

That’s one reason that it matters that this technical review is undated. Obviously, it’s crazy enough that an undated unpaginated report would show up in a report like this (I suspect it is intended to make the document hard to find).

But because it is undated and — it appears — Sussmann never got it, Durham doesn’t have to admit that he has included it in his report even after Sussmann pointed out that Durham’s inflammatory claims relied on getting the dates wrong himself.

For example, although the Special Counsel implies that in Mr. Sussmann’s February 9, 2017 meeting, he provided Agency-2 with EOP data from after Mr. Trump took office, the Special Counsel is well aware that the data provided to Agency-2 pertained only to the period of time before Mr. Trump took office, when Barack Obama was President.

After Sussmann and Joffe proved he was wrong, Durham dropped these claims. But then he resuscitated them for his report.

Durham blinds his expert so he can’t see any visibility

The second expert review Durham relied on, “FBI Cyber Division Cyber Technical Analysis Unit, Technical Analysis Report,” does have a date — April 20, 2022 — along with a Bates stamp showing that it was shared with Sussmann. The Cyber Technical Analysis Unit that wrote it is headed by David Martin, the guy who ultimately served as Durham’s expert witness at trial. After months of stalling, Durham first informed Sussmann that he would have an expert and Martin would be that expert on March 30, 2022, just weeks before trial.

Given that the Technical Analysis is dated three weeks after that, it seems exceedingly likely the Technical Analysis was a report done in preparation for Martin’s testimony.

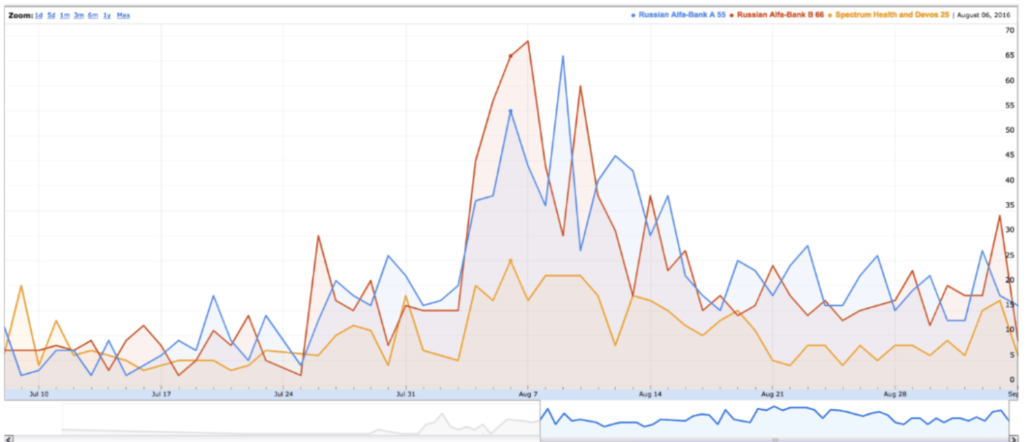

As I noted in this post, this Technical Analysis focuses exclusively on the white paper Sussmann shared on September 19, 2016.

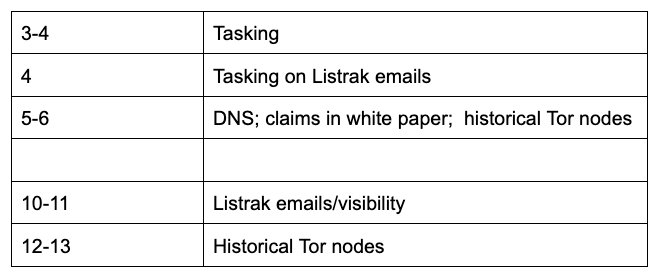

The citations to the Technical Analysis document in footnotes references just 13 pages of material, two pages of which is likely front matter, and one page describing the tasking Durham gave them.

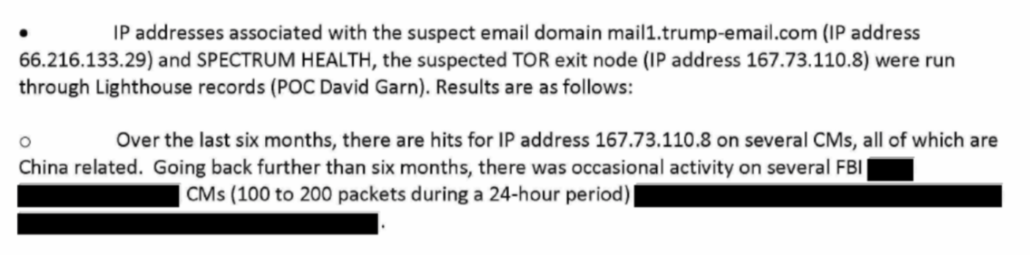

Aside from the four pages of material that Durham doesn’t mention, there are really just two topics: addressing whether or not the Spectrum Health IP address was a Tor node, and using the answers obtained from Listrak (and possibly a broader set of logs than Alison Sands had available in 2016) to make an argument about the kind of visibility one needs to learn anything from DNS records.

These topics generally track Martin’s testimony as well (though Sussmann had opposed Martin’s comments on visibility, and given that it doesn’t appear in Martin’s Powerpoint from the trial, I’m not sure he was supposed to discuss it).

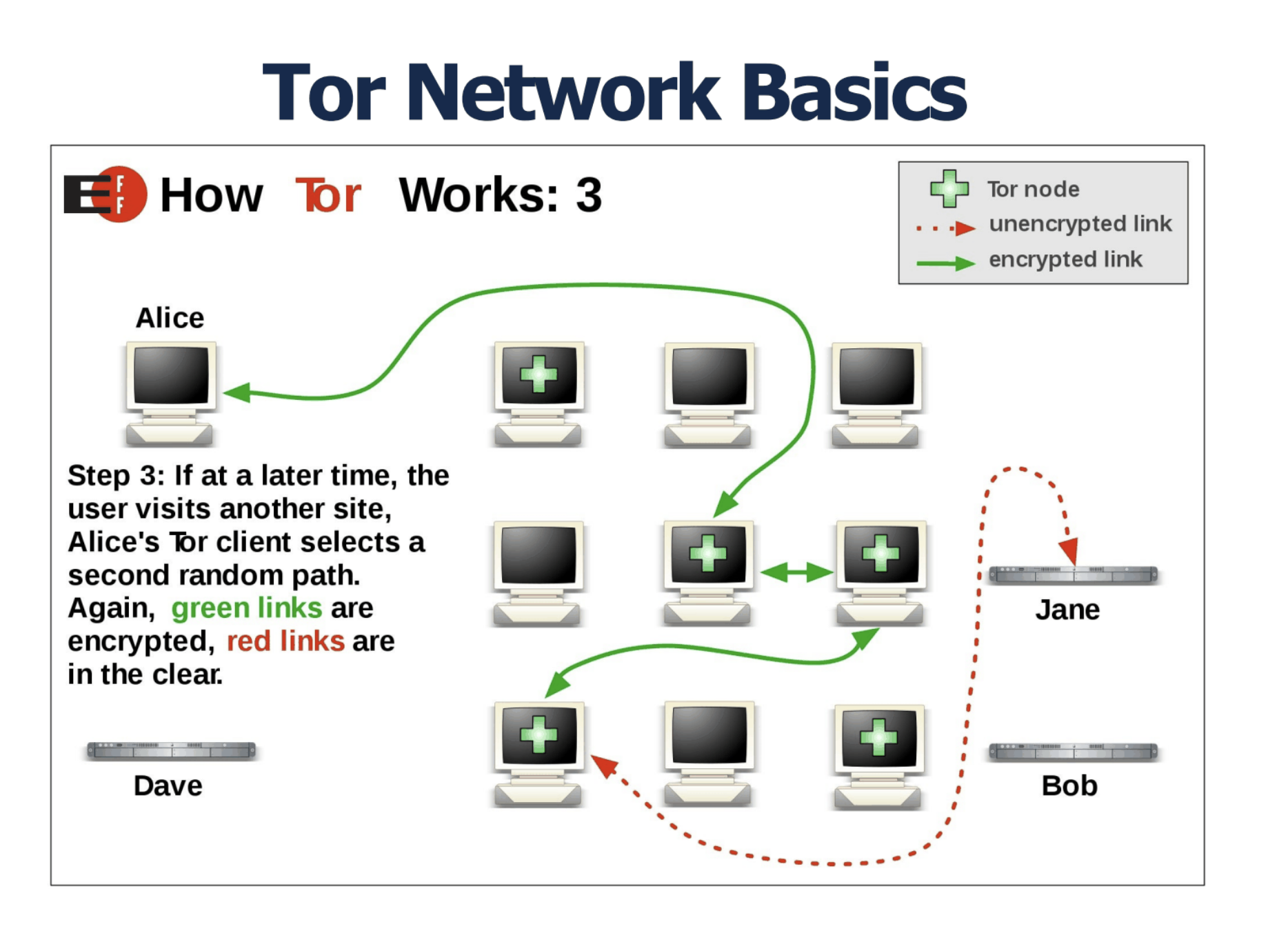

Now, Durham loves this technical analysis on Tor. He cited it first when he described how April Lorenzen was trying to figure out what the Spectrum IP address was in August 2016, and then quotes it again 30 pages later in his general technical discussion. The second time, he added an apostrophe-s which might be misread by the dim-witted people who are the audience of this propaganda to suggest that disproving that the Spectrum IP was a Tor node disproves the rest of the white paper, which it does not.

The FBI experts advised that historical TOR exit node data conclusively disproves this white paper allegation in its entirety and furthermore the construction of the TOR network makes the described arrangement impossible.

[snip]

The FBI experts who examined this issue for us stated that historical TOR exit node data conclusively disproves this white paper’s allegation in its entirety.

It’s really weird that Durham loves this analysis, because it would suggest that he didn’t learn that the Spectrum Health IP was not a Tor node until just weeks before trial — though that same judgement, that it was not a Tor node, is one of the main things the FBI got right when they first investigated this in 2016. There is almost nothing cited from this report that newbie counterintelligence agent Alison Sands hadn’t already laid out by October 5, 2016.

Durham’s fondness for this Tor node analysis is all the more hilarious because Durham tasked this expert review after the review of the files Sussmann shared with the CIA in February 2017. And neither of the files about the Alfa Bank anomaly that Sussmann turned over in 2017 (one, two) mention the Tor node. Researchers actually realized this was not a Tor node around the same time Sussmann originally shared the files. It was long gone, Durham knew it, yet that’s still the primary thing he relies on to claim he has debunked the allegations.

So Durham’s primary debunking of the white paper doesn’t address, at all, what was in the later documents. In fact, that was one effect of tasking the Cyber Technical Analysis Unit with reviewing just the stuff on the Red Thumb Drive: it gave some of FBI’s top experts a really easy way to debunk (part of) the white paper, albeit the only part that was entirely debunked in 2016.

It’s like congratulating yourself because the FBI’s top cyber experts managed to play tiddlywinks as well as a newbie counterintelligence agent did six years earlier during a rush investigation.

The second area of this technical review Durham cites that is still more telling. It purports to rely on information learned in Listrak email (not DNS) records to (effectively) accuse Joffe and the others of cherrypicking the data.

In addition to investigating the actual ownership and control of the IP address, the Office tasked FBI cyber experts with analyzing the technical claims made in the white paper. 1650 This endeavor included their examination of the list of email addresses and send times for all emails sent from the Listrak email server from May through September 2016, which is the time period the white paper purportedly examined. 1651 The FBI experts also conducted a review of the historical TOR exit node data. 1652

The technical analysis done by the FBI experts revealed that the data provided by Sussmann to the FBI and used to support Joffe and the cyber researchers’ claim that a ‘”very unusual distribution of source IP addresses” was making queries for mail l.trump-email.com was incomplete. 1653 Specifically, the FBI experts determined that there had been a substantial amount of email traffic from the IP address that resulted in a significantly larger volume of DNS queries for the mail 1.trump-email.com domain than what Joffe, University-1 Researcher-2 and the cyber researchers reported in the white paper or included on the thumb drives accompanying it. 1654 The FBI experts reviewed all of the outbound email transmissions, including address and send time for all emails sent from the Listrak server from May through September 2016, and determined that there had been a total of 134,142 email messages sent between May and August 2016, with the majority sent on May 24 and June 23. 1655 The recipients included a wide range of commercial email services, including Google and Yahoo, as well as corporate email accounts for multiple corporations. 1656

Similarly, the FBI experts told us that the collection of passive DNS data used to support the claims made in the white paper was also significantly incomplete. 1657 They explained that, given the documented email transmissions from IP address 66.216.133.29 during the covered period, the representative sampling of passive DNS would have necessarily included a much larger volume and distribution of queries from source IP addresses across the internet. In light of this fact, they stated that the passive DNS data that Joffe and his cyber researchers compiled and that Sussmann passed onto the FBI was significantly incomplete, as it included no A-record (hostname to IP address) resolutions corresponding to the outgoing messages from the IP address. 1658 Without further information from those who compiled the white paper data, 1659 the FBI experts stated that it is impossible to determine whether the absence of additional A record resolutions is due to the visibility afforded by the passive DNS operator, the result of the specific queries that the compiling analyst used to query the dataset, or intentional filtering applied by the analyst after retrieval. 1660

1653 Our experts noted that the assertion of the white paper is not only that Alfa Bank and Spectrum Health servers had resolved, or looked up, the domain [mail-1.trump-email.com] during a period from May through September of 2016, but that their resolutions accounted for the vast majority of lookups for this domain. FBI Technical Analysis Report at 6.

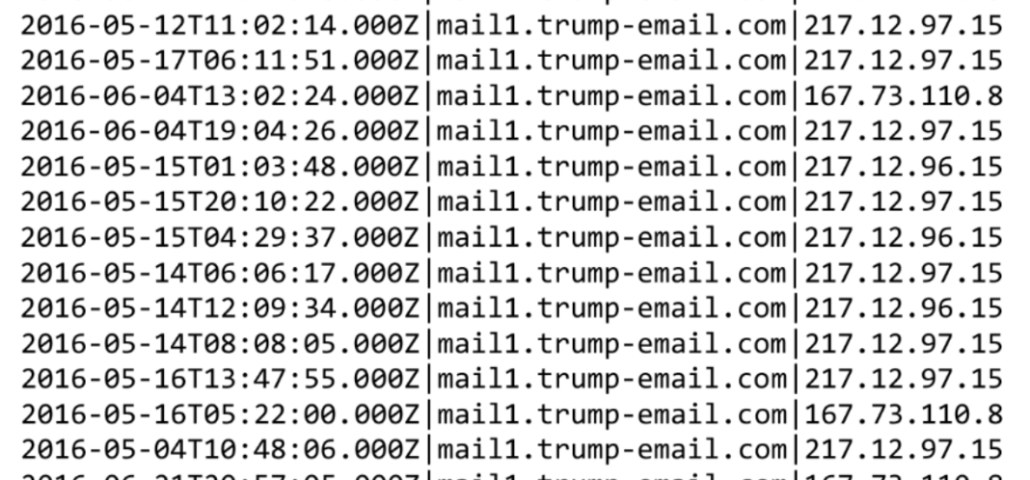

1654 The USB drive that Sussman [sic] provided to the FBI on September 19, 2016, which was proffered as data supporting the claims in the white paper, contained 851 records of DNS resolutions for domains ending in trump-email.com. FBI Technical Analysis Report at 7.

I’ll leave it to William Ockham — who apparently is smarter than the entire FBI — to explain that by looking for emails sent out from an IP rather than DNS for a domain, the FBI was basically searching for all packages from one post office rather than stamps from one house that uses that post office (I’m still working on this analogy, but it’s a start). Plus, at least in real time, the newbie counterintelligence agent who figured out the Tor node information Durham claims to have only learned six years later, Alison Sands, kept complaining that Listrak didn’t provide the network logs they needed.

But as I pointed out here, not only does the FBI change its mind mid-sentence whether there was one thumb drive or two — a problem that has plagued FBI’s Cyber division for six years, apparently –but FBI doesn’t even claim to be looking at all the data that was submitted at trial. FBI’s experts only reviewed the exact same file that Scott Hellman emphasized was a portion of the data submitted; they didn’t review the larger set. They complain they only have 851 lines of data because they’re not reviewing the larger file, much less any csv records turned over on the Blue Thumb Drive, not because the logs didn’t exist.

Remember: these are supposed to be the same people who already reviewed the CIA material by February. And the equivalent of the white paper in those materials has a passage that addresses precisely the visibility of which FBI claims to be ignorant. And the Trump/Alfa csvs included on one of those thumb drives — 2016-05-04_2017-01-15_Trump_server — not only includes almost 25,000 lines of data, but it also shows the collection points. The FBI had a way, in hand, to get that visibility, but Durham told them to look away.

The only thing the FBI’s top experts offer to debunk, other than the Tor node claim that the FBI knew the researchers had dropped, was a complaint about visibility. But their complaints about visibility were entirely manufactured by the scope of the review Durham requested and possibly by the curious status of the Blue Thumb Drive, as well as (if Durham is telling the truth about these being the same experts) willful forgetting of a review they had done on related issues less than a year earlier.

Durham created this blindness. By ensuring all the experts remain blind to visibility, Durham ensured the review would conclude that the researchers didn’t have the visibility that, the FBI knew well, they had.

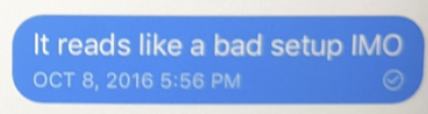

As I have described, way back in October 2016 — just days after Batty and Hellman did — I too thought that this was a set-up.

But I said that because (as I also noted) no one had seen the evidence. The FBI had the opportunity to look, but instead has spent the last six years deliberately blinding themselves so they can continue to claim it was a set-up.

Update: From pre-trial motions, here are two of the CIA summaries in which Sussmann’s claims about the YotaPhone allegations remain unredacted (one, two). They do tie the presence of the YotaPhone in EOP to Trump. But they also make it clear that the phone couldn’t have been Trump, because it didn’t always move with him, meaning these could easily have been (and still could be) someone attempting to compromise Trump.

Alfa Bank and Yotaphone Allegations

1.Factual background

a. Introduction

b. Sussmann’s attorney-client relationship with the Clinton campaign and Joffe

c. The Alfa Bank allegations

i. Actions by Sussmann, Perkins Coie, and Joffe to promote the allegation

ii. Actions by April Lorenzen and others and additional actions by Joffe

iii. Sussmann’s meeting with the FBI

d. The FBI’s Alfa Bank investigation

i. The Cyber Division’s review of the Alfa Bank allegations

ii. The opening of the FBI’s investigation

e. Actions by Fusion GPS to promote the Alfa Bank allegations

f. Actions by the Clinton campaign to promote the Alfa Bank allegations

g. Sussmann’s meeting with the CIA

h. Sussmann’s Congressional testimony

i. Perkins Coie’s statements to the media

j. Providing the Alfa Bank and Yotaphone allegations to Congress

k. Joffe’s company’s connections to the DNC and the Clinton campaign

l. Other post-election efforts to continue researching and disseminating the Alfa Bank and Yotaphone allegations

i. Continued efforts through Joffe-affiliated companies

ii. Efforts by Dan Jones and others

iii. Meetings by DARPA and Georgia Tech

iv. The relevant Trump Organization email domains and Yotaphone data

2. Prosecution decisions