I’m used to Susan Hennessey partnering with Ben Wittes to write apologies for NSA and FBI that ignore known facts. I’m a bit surprised that Jack Goldsmith did so in this defense of Democrats — like Adam Schiff and Nancy Pelosi and nineteen Democratic Senators — who have voted to give Jeff Sessions unreviewable authority to criminalize dissent using certain privacy tools.

NSA did not fix “abouts” problems before the issues became public

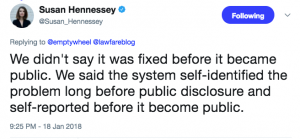

There are numerous problems with this post. The one that irks me the most, however, is the claim that the “system itself” identified and addressed problems with “abouts” collection before they became public.

We acknowledge that the program has raised hard legal questions as well as difficult compliance issues, primarily involving “abouts” collection. But these problems were identified by the system itself, long before the issues became public, and the practices were fixed or terminated.

This claim, one I’ve corrected Hennessey for on numerous occasions on Twitter, is false, and should be retracted.

I say that with great confidence, because I wrote about the problems on August 11, 2016, well before NSA failed to disclose the full extent of the problems in an October 4, 2016 hearing, which led the worst FISC judge ever, Rosemary Collyer, to complain about NSA’s institutional “lack of candor.”

At the October 26, 2016 hearing, the Court ascribed the government’s failure to disclose those IG and OCO reviews at the October 4, 2016 hearing to an institutional “lack of candor” on NSA’s part and emphasized that “this is a very serious Fourth Amendment issue.”

As a reminder, the problem (the FISC has) with “abouts” collection is not so much that it collected entirely domestic communications — that’s the complaint of the rest of us. It’s that NSA never ever complied with John Bates’ 2011 requirement that NSA not conduct back door searches on upstream collection, because it might result in searches of those entirely domestic communications. In my August 2016 post, I noted that reviewers kept discovering that NSA continued to do back door searches on upstream data in violation of that prohibition, and kept refusing to implement technical fixes to avoid them.

I also raised concerns about the oversight of 704/705(b), which is how the NSA first realized how badly non-compliant their upstream searches were, on May 13, 2016, That’s about when NSA first reported to DOJ “in May and June 2016” that “approximately eighty-five percent of” queries using a tool the NSA employs with 704/705b queries “were not compliant with the applicable minimization procedures.”

I’ll grant that I’m remarkably attentive to documents that get declassified years after the fact. But I’m nevertheless “the public.” If I’m identifying these problems — and NSA’s refusal to make the technical fixes to avoid them — before they get fully briefed to DOJ or FISC, then it is absolutely false to claim that “the system” fixed or terminated the problem long before they became public.

Again, Lawfare should issue a retraction for that claim.

Update, January 19: On Twitter yesterday, Hennessey claimed I misread this quote, and that her proof that the system works was that the NSA had gotten away with ignoring Bates’ orders for five years, but finally shut it down before the public learned that NSA had been ignoring FISC’s orders.

This is still factually false — as I responded to her, the NSA was still identifying problems for eight months after I wrote about the problems, even assuming it had found all of them by April 2017, which was the last declassified reporting on it. But her explanation actually makes the comment downright damning for the NSA. It suggests a lawyer who was at NSA during the period it was not in compliance believes that getting away with violating the Fourth Amendment for five years, but fixing it before documents released on a three year delay (and only because of Snowden) is a sign of a law-abiding agency.

A portrait of a guy who doesn’t know key details as a rigorous overseer

The fact that I was harping on the “abouts” problems before any overseers of the program managed to fully investigate and fix them by itself disproves the claims that Hennessey and Goldsmith make in their hagiography of Adam Schiff.

He is the ranking Democrat on the House intelligence committee and one of the most knowledgeable and informed members of Congress on intelligence matters. Schiff has not hesitated to be when he sees fit. He has watched the 702 program up close over many years in classified settings in his oversight role. He knows well its virtues and its warts. We suppose it is possible that Schiff would vote to give the president, whose integrity he so obviously worries about, vast powers to spy on Americans in an abusive way. Given everything Schiff has publicly said and done over the last year, however, a much more plausible inference is that he knows not only how valuable the 702 program is but also how law-constrained and carefully controlled and monitored it is.

Plus, I’m not sure why they think that Schiff’s attempt to fix the Section 215 phone dragnet only after Edward Snowden made it public proves that Schiff “never hesitated to be critical of intelligence community practices.” On the contrary, it proves that he did hesitate to do so before excessive programs became public.

The distinction is utterly critical given something I’ve pointed out about this bill. The bill itself is an admission that the intelligence community is out of control, and that congressional overseers can’t get information they need to adequately oversee the program without demanding it in legislation. That’s because it requires the IC to provide information on two practices that Congress cannot be deemed competent to legislate on without having answers about first.

For example, the bill requires an IG Report on how FBI queries raw data.

(b) MATTERS INCLUDED.—The report under subsection (a) shall include, at a minimum, an assessment of the following:

(1) The interpretations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the National Security Division of the Department of Justice, respectively, relating to the querying procedures adopted under subsection (f) of section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1881a(f)), as added by section 101.

[snip]

(6) The scope of access by the criminal division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to information obtained pursuant to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1801 et seq.), including with respect to information acquired under subsection (a) of such section 702 based on queries conducted by the criminal division.

(7) The frequency and nature of the reviews conducted by the National Security Division of the Department of Justice and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence relating to the compliance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation with such querying procedures.

I have explained (and I know Hennessey regards this as a problem too) that since 2012, FBI has devolved its access to raw 702 data to field offices. The FBI already conducted far, far less oversight of the back door searches it conducts than NSA does. But because the DOJ/DNI 702 review teams visit only a fraction of the FBI field offices with each review, and because FBI’s querying system doesn’t collect enough information to do oversight remotely, it is possible that the offices that are least familiar with 702 requirements are — for the smaller number of 702 queries they conduct — getting the least oversight.

You can’t pass a bill that effectively blesses FBI’s use of back door searches on Americans about whom it has no evidence of any wrongdoing, while admitting you don’t know how FBI conducts those back door searches, and make any claim to conduct adequate oversight. Rather, the bill permits FBI to continue practices it has stubbornly refused to brief Congress on, rather than demanding that FBI brief Congress first, so Congress can impose any restrictions that might be necessary to adequately protect Americans.

The bill also requires a briefing within six months to explain how DOJ complies with FISA’s legally mandated notice requirements (because notice under 702 is treated as notice under 106(c), this covers 702 surveillance as well).

Not later than 180 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Attorney General, in consultation with the Director of National Intelligence, shall provide to the Committee on the Judiciary and the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence of the House of Representatives and the Committee on the Judiciary and the Select 10 Committee on Intelligence of the Senate a briefing with respect to how the Department of Justice interprets the requirements under sections 106(c), 305(d), and 405(c) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 14 U.S.C. 1806(c), 1825(d), and 1845(c)) to notify an aggrieved person under such sections of the use of information obtained or derived from electronic surveillance, physical search, or the use of a pen register or trap and trace device. The briefing shall focus on how the Department interprets the phrase ‘‘obtained or derived from’’ in such sections.

The public treatment of DOJ’s serial, obvious failures to give notice to defendants is a nifty trick. When DOJ fails to give notice, it clearly violates the law, but notice is not included in minimization procedure review, so therefore is not reviewed by the FISC. When surveillance boosters like Hennessey and Goldsmith say there have never been any willful violations of the law, they manage to ignore the notice violations that have allowed some pretty problematic practices to avoid judicial oversight only because by breaking the law DOJ ensures no court will find them to be breaking the law.

Catch 22: Heads legal violations never get reviewed by a court, tails surveillance boosters can claim the surveillance has a clean bill of health.

Again, this is a known, egregious problem with the implementation of 702.

But rather than do the obvious thing as part of what this post dubs “robust democratic deliberation,” which is to demand answers about how notice is (not) given and require DOJ to fix it as part of the bill, the bill instead simply requires DOJ to provide the information that Congress needs to do basic oversight six months after reauthorization, which effectively punts fixing the problem six years down the road.

How many Chinese-American scientists will be improperly prosecuted because FBI is technically inane in those 6 years, because a bunch of California legislators like Nancy Pelosi, Adam Schiff, and Dianne Feinstein chose to punt on basic oversight?

The most egregious example of this, however, involves the government’s obstinate refusal to explain how many US persons are affected by 702. This bill also did not incorporate an HJC proposal requiring a count of how many Americans got referred for criminal prosecution off of 702 collection.

Letting Jeff Sessions criminalize dissent

That refusal — the refusal to even legislatively require the government to report on the impact of 702 surveillance on Americans, via incidental collection and/or criminal referral — brings us to the problem with this bill that opponents are all raising, but about which Hennessey and Goldsmith are inexcusably silent: the codification of giving Jeff Sessions unreviewable authority to determine what counts as a “criminal proceeding [that] affects, involves, or is related to the national security of the United States.”

Here’s how Hennessey and Goldsmith describe the impact of this program on Americans.

As Lawfare readers know, Section 702 authorizes the intelligence community to target the communications of non-U.S. persons located outside the United States for foreign intelligence purposes. It does not permit the intelligence community to target a U.S. person anywhere in the world. But it does permit incidental collection on U.S. persons, subject to strict rules about minimization and use.

Their silence about how the bill doesn’t deal with back door searches is problematic enough.

But they predictably, but problematically, make no mention of the way the bill codifies the use of 702 in domestic law enforcement under the Tor/VPN exception.

As I have laid out, in 2014 FISC created an exception to the rule that NSA must detask from a facility as soon as they learn that Americans are also using that facility. That exception applies to Tor and (though I understand this part even less) VPN servers — basically the kinds of privacy tools that criminals, spies, journalists, and dissidents might use to hide their online activities. NSA has to sort through what they collect on the back end, but along the way, they get to decide to keep any entirely domestic traffic they find has significant foreign intelligence purpose or is evidence of a crime, among other reasons. The bill even codifies 8 enumerated crimes under which they can keep such data. Some of those crimes — child porn and murder — make sense, but others — like transnational crime (including local drug dealers selling imported drugs) and CFAA (with its well-known propensity for abuse) pose more potential for abuse.

But it’s the unreviewable authority for Jeff Sessions bit that is the real problem.

We know, for example, that painting Black Lives Matter as a national security threat is key to the Trump-Sessions effort to criminalize race. We also know that Trump has accused his opponents of treason, all for making critical comments about Trump.

This bill gives Sessions unreviewable authority to decide that a BLM protest organized using or whistleblowing relying on Tor, discovered by collection done in the name of hunting Russian spies, can be referred for prosecution. The fact that the underlying data predicating any prosecution was obtained without a warrant under 702 would — in part because this bill doesn’t add teeth to FISA notice — ensure that courts would never learn the genesis of the prosecution. Even if a court somehow managed to do so, however, it could never deem the domestic surveillance unlawful because the bill gives Jeff Sessions the unreviewable authority to treat dissent as a national security threat.

This is such an obviously bad idea, and it is being supported by people who talk incessantly about the threat that Trump and Sessions present. Yet, rather than addressing the issue head on (which I doubt Hennessey could legally do in any case), they simply remain silent about what is the biggest complaint from privacy activists, that this gives a racist, vindictive Attorney General far more authority than he should have, and does so without fixing the inadequate protections for criminal defendants along the way.

I mean, I get that surveillance boosters who recognize the threat Trump and Sessions pose want to absolve themselves for giving Trump tools that can so obviously be abused.

But this attempt does so precisely by dodging the most obvious reasons for which boosters should be held to account.

Update: Changed post to note that just Trump has accused FBI Agents of treason, not Sessions, and not (yet) journalists.

Update: Here’s the roll call of the 65-34 vote passage of the bill. Democrats who voted in favor are:

- Carper

- Casey

- Cortez Masto

- Donnelly

- Duckworth

- Feinstein

- Hassan

- Heitkamp

- Jones

- Klobuchar

- Manchin

- McCaskill

- Nelson

- Peters

- Reed

- Schumer

- Shaheen

- Stabenow

- Warner

- Whitehouse

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)