When Insisting on the Letter of the Law Counts Amounts to Being “Hyper-Technical”

After almost two months, the Magistrate in the MalwareTech case, Nancy Joseph, has finally responded to his motions to dismiss his interview and most charges in the indictment (here’s my snarky summary of the arguments the judge considered, with links to those motions). She ruled against him on every motion.

I won’t deal with Hutchins’ challenge to his interview statements; as I’ve said all along, that was unlikely to succeed, but the process of getting here did introduce evidence that should damage the arresting officers’ credibility on the stand for the trial.

There may be no evidence in the CFAA charges but there is enough to withstand this challenge

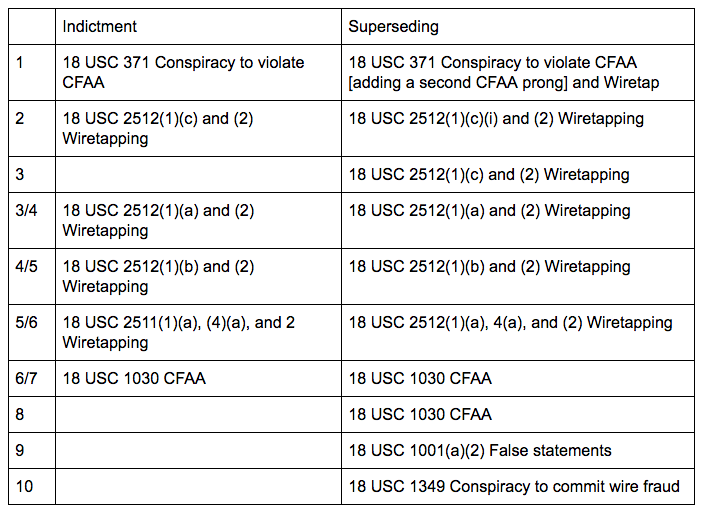

Hutchins’ first challenge is to a series of Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and Wiretapping charges, which his team argued did not correctly apply the statutes.

Hutchins moves to dismiss the first superseding indictment for failure to state an offense under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 12(b). In this motion, Hutchins contends that (1) Counts One and Seven fail to allege any facts that show he intended to cause “damage” to a computer within the meaning of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act; (2) Counts One through Six do not state an offense because software such as Kronos and UPAS Kit is not an “electronic device” within the meaning of the Wiretap Act; and (3) Counts One, Four through Eight, and Ten do not allege the necessary intent and causation required to prove a conspiracy.

In her recommendation, Joseph suggests there may not be proof to support these charges, but unless this challenge is an issue regarding the application of the law to a set of undisputed facts, then insufficient evidence is not adequate to throw out a charge.

On a pretrial motion to dismiss, an indictment “is reviewed on its face, regardless of the strength or weakness of the government’s case.” White, 610 F.3d at 958. A defendant may not, via pretrial motion, challenge the sufficiency of the government’s proof. See United States v. Yasak, 884 F.2d 996, 1001 (7th Cir. 1989) (“A motion to dismiss is not intended to be a ‘summary trial of the evidence.’”). The court dismisses an indictment only if the government’s inability to prove its case appears convincingly on the face of the indictment. Castor, 558 F.2d at 384.

With this and later charges, she then analyzes the sufficiency of the indictment based on whether it includes the language of the statute, not whether it uses that language in the way the Circuit has ruled it should be or Congress intended it. So, in spite of the fact that there’s no evidence Hutchins had the intent to damage computers, because the government has defined programs Hutchins contributed to as “malware” and then defined malware as “code intended to damage a computer” (which, Hutchins argued, is not how the Seventh Circuit defines malware) their charge is sufficient.

Hutchins ignores that the indictment itself describes Kronos and UPAS Kit as “malware,” which it defines as “malicious computer code intended to damage a computer.” (Id. at 1(d)–(f).) That is sufficient to allege intent to cause damage. The crux of Hutchins’ argument is that the government cannot prove this.

Asking that the government adhere to the law as Congress wrote it is “hyper-technical”

Similarly, in spite of the fact that Congress defined wiretapping as an “electronic, mechanical, or other evidence,” Joseph says the way the government applies it instead to software passes muster until Hutchins proves that software is not hardware at trial.

Hutchins argues that the Wiretap Act’s definition of this phrase, “any device or apparatus which can be used to intercept a wire, oral, or electronic communication,” does not include software because software is not within the ordinary meaning of “device.”

As noted above, it is not appropriate to dismiss criminal indictments without undisputed facts supporting the conclusion that a jury trial is unnecessary. While the indictment briefly defines Kronos and UPAS Kit, the details of their functions and their relationships to more traditional “devices” such as computers will be a matter for the jury.

Permitting the government to sustain any possible definition of wiretapping

Her decision to permit the government to define malware as a device makes it unsurprising that she keeps both charges two and three, which charge the same advertising a wiretapping device twice. The government defended this charging decision based on its assertion of the right to pick its own dictionary, and having already ceded the government that authority, keeping both charges two and three is consistent with her other decisions.

Mistaking the conspiracy for the direct sale

The way in which Joseph dismisses Hutchins’ challenge to how the government charged him with conspiracy to commit CFAA is curious for other reasons. This is a conspiracy case, and while I think it possible the government could succeed at trial in arguing that because Hutchins’ alleged co-conspirator fully intended his customers (like the government’s informant) to hack computers, that means he entered into a conspiracy to do so. Joseph doesn’t rely on the powerful way the government uses conspiracy charges at all. Indeed, she edits out mention of that co-conspirator, without whom no sale would have taken place.

Hutchins argues that the indictment “conflates [Hutchins’] alleged selling of the software with a specific intent for buyers to commit an illegal act with the software. There is no allegation that Mr. Hutchins . . . intended any specific result to occur because of the sales. . . . Merely writing a program and selling it—when any illegal activity is up to the buyer to perform—is not enough to allege specific intent by Mr. Hutchins.” (Id. at 95.) Here again, Hutchins tries to impose a standard for civil pleading on a criminal indictment.

The language about intent and causation tracks the statutory elements, and that is all that is required in an indictment.

Effectively, Joseph seems to be arguing a CFAA charge itself rather than a conspiracy to commit CFAA charge. That’s problematic given that Hutchins raised a Seventh Circuit standard applying to conspiracies to sell stuff (drugs) that would be on point.

Intentionality is required but attempts are sufficient

In one of the charges where Hutchins is personally charged with CFAA, rather than conspiracy, Joseph permits the government’s effort to effect a conspiracy anyway, by first agreeing that intent is required, but then saying that attempting to do something even in absence of intent amounts to intent anyway.

To prove an attempt to violate § 1030(a)(5)(A), the government must prove that (1) Hutchins knowingly took a substantial step toward committing a violation of § 1030(a)(5)(A) and (2) that he did so with the intent to violate § 1030(a)(5). Seventh Circuit Pattern Jury Instruction 4.09. Accordingly, although Hutchins is correct that §1030(a)(5) does require that the damage be intentional, he is incorrect that the charge does not allege intentionality. It alleges an attempt, and intentionality is a necessary component of an attempt. In other words, the phrase “intentionally attempted” would be redundant.

Because Count Seven, read practically and not in a hyper-technical manner, sets forth the elements of an attempt to violate § 1030(a)(5), it is sufficient.

Again, “hyper-technical” is doing a lot of work here.

A YouTube in California is an overt act in Wisconsin

Hutchins may have fucked himself a bit by waiving all venue challenges to Wisconsin (venue here comes from an Agent buying two pieces of malware and then committing no crimes with it). Still, his argument clearly lays out parts of the government’s claim that he can be charged in the United States — notably, via a YouTube had no tie to and his co-conspirator only linked — that argue there were no overt acts in the US.

Joseph ignores the parts of the argument where Hutchins lays out that the government doesn’t argue any basis for venue and declares the allegations sufficient.

Count One alleges various acts in furtherance of a conspiracy resulting in the sale of UPAS Kit and Kronos to individuals in the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

Of course, Hutchins is correct that an offense cannot be prosecuted anywhere in the world just because it involves the Internet. (Docket # 105 at 5.) But the indictment does not do that. On the contrary, it alleges that relevant events occurred in the state and Eastern District of Wisconsin. Whether the government will be able to prove that is a question for another day. At this juncture, it is sufficient that the indictment alleges that the violations occurred within the state and Eastern District of Wisconsin.

Dodging the issue of the informant who is the only one who has damaged or wiretapped computers

Joseph effectively dodges the entirety of Hutchins’ renewed demand for the identity of “Randy,” the informant whom the government describes as the only one who actually damaged (if malware damages computers) or wiretapped anything, which is that Randy is an unindicted co-conspirator, not an informant. She just says 30 days notice of Randy’s identity is sufficient.

The hyper-technical problems with treating malware as a device

It’s in the Wiretap Act where this ruling is most alarming. Joseph twice appears to misunderstand that Hutchins is not alleged to have wiretapped anything himself, but instead coded malware that his alleged co-conspirator sold, which other then people used to collect data (as noted, the government’s informant is the only one alleged to have illegally collected any data here).

In the absence of more details, it is unwarranted at this stage to evaluate whether they alone qualify as “devices” or to assume that the government could not produce evidence that Hutchins did in fact use an indisputable “device” of some kind, if not the software itself than a computer or some other device.

[snip]

There is simply no authority for the argument that software cannot constitute a “device” within the meaning of the Wiretap Act, and even if there were, there are simply not sufficient facts before the court to determine that Hutchins did not violate the Wiretap Act using some “device” in connection with Kronos and UPAS Kit. [my emphasis]

More troubling still, in adopting the government’s expansive definition of wiretapping, she suggests doing otherwise is “hyper-technical.”

[T]here are reasons to doubt such a strict interpretation of the Wiretap Act would be warranted even if this court were to undertake such an interpretation. Determining that the Wiretap Act could never apply to software would require the court to overlook the notably broad language of the Wiretap Act, which was to generally prohibit unauthorized artificial interception of communication in an era of changing technologies, in favor of a hyper-technical reading of the statute. It would also require the court to adopt a very restrictive definition of “electronic, mechanical, or other device” that may not comport with legislative intent, the ordinary meaning of those words, or the (scant) existing case law. Cf. Luis v. Zang, 833 F.3d 619 (6th Cir. 2016); In re Carrier IQ, Inc., 78 F. Supp. 3d 1051 (N.D. Cal. 2015).

Most charitably, this should be taken as a punt. Because Joseph doesn’t realize that the facts are almost undisputed (because the government admitted that in this case a computer would be the device doing any wiretapping, not the malware itself), she dodges the issue of law that, she says, could be the appropriate standard for dismissal.

But in fact, it reverses the burden, permitting prosecutors to invent new readings of law, and permitting that reading until such time as Hutchins demonstrates at trial that’s explicitly not what Congress intended.

Ultimately, though, it seems that Joseph has been staring at several well-substantiated technical arguments about how the law is written and, having despaired of understanding that, simply declared treating the law as it was either written or has been interpreted by the Courts amounts to being “hyper-technical” and punted that job to the jury. That’s not surprising. Indeed, that’s one of the grave risks of defending against a hacking charge in a place that sees little of it. But everywhere where Hutchins made a legal careful argument, Joseph either let the government invent different meanings willy nilly or just deferred all treatment of the technical issues to trial.