John Lewis Was Not Always Old

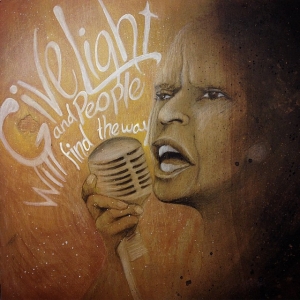

“Ode to Ella Baker” by Lisa McLymont (Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0)

A few weeks ago, John Lewis put out a press release announcing to all that he is undergoing treatment for stage 4 pancreatic cancer. He later sent out a tweet, lifting up one of the best lines in that press statement:

I have been in some kind of fight – for freedom, equality, basic human rights – for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now.

Lewis’ summary of his life is not hyperbole. He is the last living member of the Big Six, the speakers at the 1963 March on Washington for civil rights, and now is a senior member of Congress. But it’s important to remember that John Lewis was not always old. He was just 23 when he spoke on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial as the president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) – an organization he co-founded three years earlier at age 20 – and at 21 was one of the original Freedom Riders.

Let me repeat it again: John Lewis was not always old. He has always been a fighter for civil rights, but he has not always been old.

In 2005, historian David McCullough noted how we as a society perceive great leaders in a speech about the Founders:

We tend to see them—Adams, Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Rush, George Washington—as figures in a costume pageant; that is often the way they’re portrayed. And we tend to see them as much older than they were because we’re seeing them in the portraits by Gilbert Stuart and others when they were truly the Founding Fathers—when they were president or chief justice of the Supreme Court and their hair, if it hadn’t turned white, was powdered white. We see the awkward teeth. We see the elder statesmen.

At the time of the Revolution, they were all young. It was a young man’s–young woman’s cause. George Washington took command of the Continental Army in the summer of 1775 at the age of 43. He was the oldest of them. Adams was 40. Jefferson was all of 33 when he wrote the Declaration of Independence. Benjamin Rush—who was the leader of the antislavery movement at the time, who introduced the elective system into higher education in this country, who was the first to urge the humane treatment of patients in mental hospitals—was 30 years old when he signed the Declaration of Independence. Furthermore, none of them had any prior experience in revolutions; they weren’t experienced revolutionaries who’d come in to take part in this biggest of all events. They were winging it. They were improvising.

This is not unique to the American Founders. Historians of social change who pay attention to the leaders of these movements often see the same thing. For example . . .

- When Martin Luther King, Jr. led the Montgomery Bus boycott in 1955, he was just shy of 25 years old. When he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, he was 35, and when was assassinated on the balcony of a Memphis hotel, he was only 39.

- When Thurgood Marshall argued on behalf of racial justice in Shelley v. Kramer before SCOTUS in 1948 – six years before he did the same in Brown v. Board of Education – Marshall was 40 years old. He won both cases, the former striking down restricted housing covenants and the latter doing away with the pernicious “separate but equal” doctrine that was at the heart of Jim Crow.

- When Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo, and Nelson Mandela co-founded the ANC Youth League in 1944, they were 31, 26, and 25 years old respectively.

- When Dr. Paul Volberding and nurse Cliff Morrison pushed against incredible medical and social prejudices to organize the nation’s first AIDS unit at San Francisco General Hospital in 1983 as the AIDS crisis continued to spiral out of control, they were 33 and 31 respectively.

- When Gavin Newsom (then mayor of San Francisco) ordered the San Francisco clerk’s office to issue marriage licenses for couples regardless of the genders involved on February 14, 2004, he was 36.

- When Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, exposing the ugly underside of the meatpacking industry and spurring social change with regard government oversight and regulation of food and drugs, he was 28.

- When anti-lynching crusader and journalist Ida B. Wells published Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases in 1892, she was 30.

- When Elizabeth Cady Stanton co-organized the Seneca Falls Conference on Women’s Rights in 1848, she was 32.

It’s not too much of a stretch to say that the leaders of social change movements are more likely to be young than to be old.

After Lewis made his announcement, Marcy tweeted out her reactions to the news, including this:

Say a prayer–or whatever you do instead–to give John Lewis strength for this fight. But also commit to raise up a young moral leader who has inspired you. We can’t rely on 80 and 90 year olds to lead us in the troubled days going forward.

I’ve been chewing on that tweet for the better part of a month.

What immediately went through my head upon reading that tweet was the name Ella Baker, one of the less well-known leaders in the civil rights movement. In a story for the Tavis Smiley Show on PRI about the founding of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), John Lewis tells of Ella’s powerful role:

Martin Luther King, Jr. was so impressed by the actions of the students [and their non-violent lunchcounter sit-ins], says Lewis, that he asked a young woman by the name of Ella Baker to organize a conference, inviting students from 58 colleges and universities.

“More than 300 people showed up at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, where SNCC was born,” said Lewis. “It was Easter weekend, 1960.”

Baker, considered by many as an unsung hero of the civil rights movement, was a “brilliant” radical who spurred on the creation of SNCC as an independent organization, says Lewis.

“She was a fiery speaker, and she would tell us to ‘organize, organize; agitate, agitate! Do what you think is right. Go for it!’ Dr. King wanted her to make SNCC the youth arm of his organization. But Ella Baker said we should be independent … and have our own organization.”

While the SNCC was deeply inspired by Dr. King and the SCLC, or the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the students in the organization didn’t always see eye-to-eye with SCLC leadership.

“We had a lot of young women, and SNCC didn’t like the idea of the male chauvinism that existed in the SCLC,” says Lewis. “The SCLC was dominated by primarily black Baptist Ministers. And these young women did all the work and they had been the head of their local organizations.”

I’m not sure where Smiley got the phrasing about Ella Baker being “a young woman” when this all happened, as she was 55 years old in 1960 and King was only 30. But Ella did exactly what Marcy was talking about in that tweet. When she saw an opening to act, she helped raise up hundreds of young moral leaders, and she helped them most by encouraging them to act out of their own gifts and strengths and not by tying themselves to the approaches of older leaders.

Which brings me to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. In the days following the massacre at MSD, the students there took matters into their own hands, rather than waiting for their elders to act. These are kids who grew up entirely in the post-Columbine High School shooting world, where active shooter drills were a regular part of school life. (I’m old: the only drills we had were “duck and cover” for a nuclear attack and “head for the hallway or basement” for tornadoes.) With each new shooting, they saw the same script written by the elders play out each time – thoughts and prayers for the victims, debate over gun laws, and nothing changes. They saw it happen around the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando a year and a half earlier. Talk, talk, talk and nothing changes.

This time, it wasn’t the elders running the show, however. It was Emma Gonzales, live on every cable network, who called BS on the NRA and the legislators who were intimidated by them. It was Cameron Kasky who gathered and organized his classmates to make this a movement. It was David Hogg and a dozen others, a hundred others, who did interviews, organized demonstrations, and the 1001 other things to give their work power. They reached out to other teens affected by gun violence, especially teens of color, to amplify the common message demanding change. They became a force to be reckoned with, not only in Tallahassee where they actually got gun laws changed, but in DC and around the country.

Behind these students, though, were their teachers. These are the folks who nourished the gifts of research and organization, of public speaking and political organizing in these young people. There were parents and other adults, who took their cues from the teens and did the things that you need someone over 21 to do, like sign rental bus agreements, for example. It is clear, though, that the moral leaders are the teens, with the elders in supporting roles.

Then there’s Greta Thunberg, relentlessly pushing the elders in seats of power to take action on the climate emergency gripping our planet. Her messages are always a version of “This is not about me and my knowledge; it’s about the scientists and their knowledge – and they say we are going to burn the planet down if things don’t change fast.” She points to data, and forces her hearers to look at it. She may have gotten attention early on because of her youth (“O look at that cute little girl, doing cute little things and trying to get politicians to act”), but being a cute little girl doing cute little things doesn’t get you seat at the table at Davos. No, she got her seat at the tables of the powerful by being the young person who said over and over and over again that the emperors, the presidents, the corporate titans, and the powers of the planet aren’t wearing any clothes.

Just like young John Lewis.

The other part of Greta’s “It’s not about me” messaging is that she has sought out and nurtured other young people around the world, who have been organizing in their communities while she was at work in Sweden. She met Lakota activist Tokata Iron Eyes, who invited her to Standing Rock to see the work they are doing. Thunberg not only accepted, but eagerly lent her support to their work, not least of which came because of her larger media profile. When she spoke at Davos, it was as part of a panel of other young climate activists from Puerto Rico, southern Africa, and Canada.

Like the MSD students, Greta has passion for her activism, a data-driven focus that she hope can break through the cynicism and self-centeredness of world leaders, and a skill at building alliances with other like minded folks. And like the MSD students, people with power are listening — and are beginning to want to hear more. While Steve Mnuchen (following the lead of Donald Trump) mocked Thunberg for her youth, another world leader had a different reaction:

Angela Merkel, though, spoke warmly about the work of the new generation of climate activists.

“The impatience of our young people is something that we should tap,” the German chancellor said. In a special address to the WEF, Merkel called for more international cooperation to tackle climate change.

“I am totally convinced that the price of inaction will be far higher than the price of action,” she declared.

Over the last month, I’ve been looking at and interacting with the teenagers in my life a little bit differently, a little more intentionally, thanks in part to Marcy’s tweet. You see, one of those teens may just be another John Lewis, and I’d dearly love to be another Ella Baker.