I hope to write a post arguing that Peter Strzok’s book came out at least six months too late.

But for the moment, I want to float the possibility that Nora Dannehy — John Durham’s top aide — quit last Friday at least in part because she read parts of Strzok’s book and realized there were really compelling answers to questions that have been floating unasked — and so unanswered — for years.

High-gaslighter Catherine Herridge raises questions already answered about Crossfire Hurricane opening

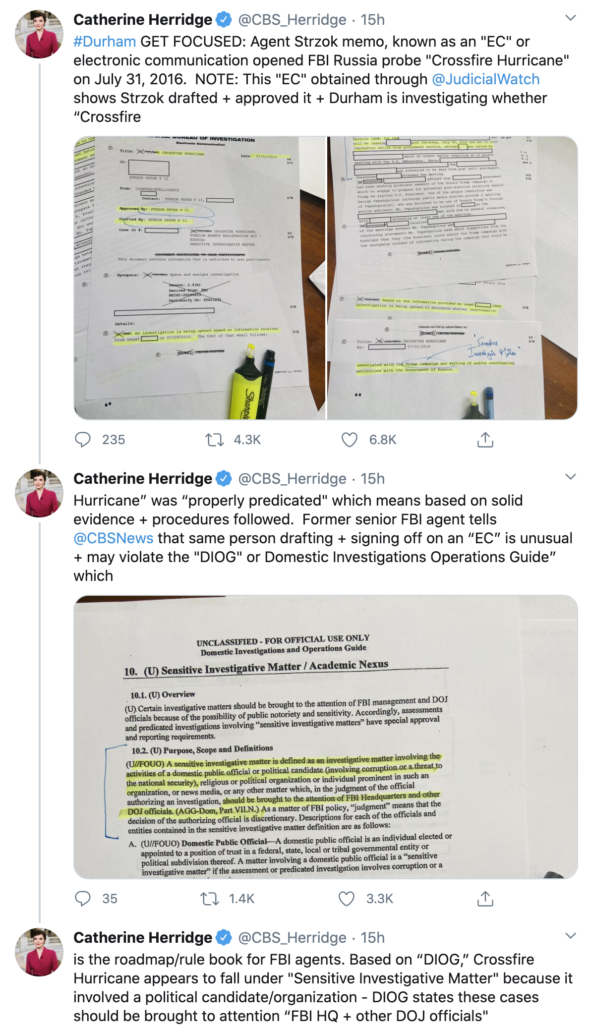

Yesterday, the Trump Administration’s favorite mouthpiece for Russian investigation conspiracies, Catherine Herridge, got out her high-gaslighter to relaunch complaints about facts that have been public (and explained) for years.

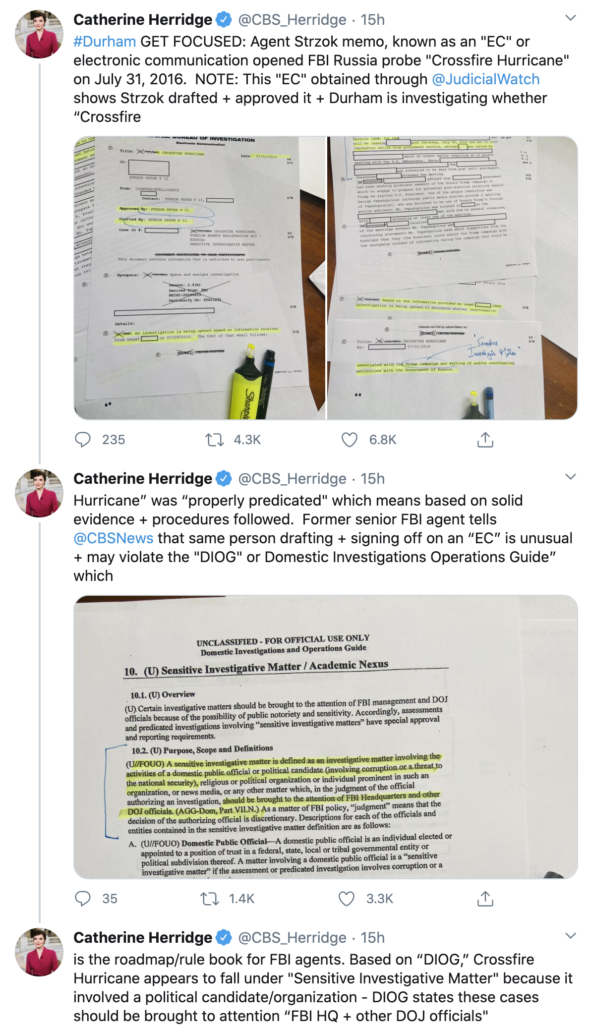

Citing an unnamed “former senior FBI Agent” and repeating the acronym “DIOG” over and over to give her high-gaslighting the patina of news value, she pointed to the fact that Strzok both opened and signed off on the Electronic Communication opening Crossfire Hurricane, then suggested — falsely — that because Loretta Lynch was not briefed no one at DOJ was. It’s pure gaslighting, but useful because it offers a good read on which aspects of Russian investigation conspiracies those feeding the conspiracies feel need to be shored up.

Note, even considering just the ECs opening investigations, Herridge commits the same lapses that former senior FBI Agent Kevin Brock made in this piece. I previously showed how the EC for Mike Flynn addresses the claimed problems. I’m sure it’s just a coincidence that Herridge’s anonymous former senior FBI Agent is making the same errors I already corrected when former senior FBI Agent Kevin Brock made them in May.

All that said, I take from Herridge’s rant that her sources want to refocus attention on how Crossfire Hurricane was opened.

Peter Strzok never got asked (publicly) about how the investigation got opened

As it happens, that’s a question that Strzok had not publicly addressed in any of his prior testimony.

Strzok was not interviewed by HPSCI.

Strzok was interviewed by the Senate Intelligence Committee on November 17, 2017. But they don’t appear to have asked Strzok about the investigation itself or much beyond the Steele dossier; all six references to his transcript describe how the FBI vetted the Steele dossier.

Deputy Assistant Director Pete Strzok, at that point the lead for FBI’ s Crossfire Hurricane investigation, told the Committee that his team became aware of the Steele information in September 2016. He said, “We were so compartmented in what we were doing, [the Steele reporting] kind of bounced around a little bit,” also, in part, because [redacted] and Steele did not normally report on counterintelligence matters. 5952 Strzok said that the information was “certainly very much in line with things we were looking at” and “added to the body of knowledge of what we were doing.”5953

Peter Strzok explained that generally the procedure for a “human validation review” is for FBI’ s Directorate of Intelligence to analyze an asset’s entire case file, looking at the reporting history, the circumstances of recruitment, their motivation, and their compensation history.6005 Strzok recalled that the result was “good to continue; that there were not significant concerns, certainly nothing that would indicate that he was compromised or feeding us disinformation or he was a bad asset.”6006 However, Strzok also said that after learning that reporters and Congress had Steele’s information:

[FBI] started looking into why he was assembling [the dossier], who his clients were, what the basis of their interest was, and how they might have used it, and who would know, it was apparent to us that this was not a piece of information simply provided to the FBI in the classic sense of a kind of a confidential source reporting relationship, but that it was all over the place. 6007

[snip]

Strzok said that, starting in September 2016, “there were people, agents and analysts, whose job specifically it was to figure this out and to do that with a sense of urgency.”6021

Strzok was also interviewed in both a closed hearing and an open hearing in the joint House Judiciary and House Oversight investigations into whatever Mark Meadows wanted investigated. The closed hearing addressed how the investigation got opened, but an FBI minder was there to limit how he answered those questions, citing the Mueller investigation. And even there, the questions largely focused on whether Strzok’s political bias drove the opening of the investigation.

Mr. Swalwell. Let me put it this way, Mr. Strzok: Is it fair to say that, aside from the opinions that you expressed to Ms. Page about Mr. Trump, there was a whole mountain of evidence independent of anything you had done that related to actions that were concerning about what the Russians and the Trump campaign were doing?

Ms. Besse. So, Congressman, that may go into sort of the — that will — for Mr. Strzok to answer that question, that goes into the special counsel’s investigation, so I don’t think he can answer that question.

Even more of the questions focused on the decision to reopen the Clinton investigation days before the election.

To the extent that the open hearing, which was a predictable circus, addressed the opening of Crossfire Hurricane at all (again, there was more focus on Clinton), it involved Republicans trying to invent feverish meaning in Strzok’s texts, not worthwhile oversight questions about the bureaucratic details surrounding the opening.

The DOJ IG Report backs the Full Investigation predication but doesn’t explain individual predication

The DOJ IG Report on Carter Page does address how the investigation got opened. It includes a long narrative about the unanimity about the necessity of investigating the Australian tip (though in this section, it does not cite Strzok).

From July 28 to July 31, officials at FBI Headquarters discussed the FFG information and whether it warranted opening a counterintelligence investigation. The Assistant Director (AD) for CD, E.W. “Bill” Priestap, was a central figure in these discussions. According to Priestap, he discussed the matter with then Section Chief of CD’s Counterespionage Section Peter Strzok, as well as the Section Chief of CD’s Counterintelligence Analysis Section I (Intel Section Chief); and with representatives of the FBI’s Office of the General Counsel (OGC), including Deputy General Counsel Trisha Anderson and a unit chief (OGC Unit Chief) in OGC’s National Security and Cyber Law Branch (NSCLB). Priestap told us that he also discussed the matter with either then Deputy Director (DD) Andrew McCabe or then Executive Assistant Director (EAD) Michael Steinbach, but did not recall discussing the matter with then Director James Comey told the OIG that he did not recall being briefed on the FFG information until after the Crossfire Hurricane investigation was opened, and that he was not involved in the decision to open the case. McCabe said that although he did not specifically recall meeting with Comey immediately after the FFG information was received, it was “the kind of thing that would have been brought to Director Comey’s attention immediately.” McCabe’s contemporaneous notes reflect that the FFG information, Carter Page, and Manafort, were discussed on July 29, after a regularly scheduled morning meeting of senior FBI leadership with the Director. Although McCabe told us he did not have an independent recollection of this discussion, he told us that, based upon his notes, this discussion likely included the Director. McCabe’s notes reflect only the topic of the discussion and not the substance of what was discussed. McCabe told us that he recalled discussing the FFG information with Priestap, Strzok, then Special Counsel to the Deputy Director Lisa Page, and Comey, sometime before Crossfire Hurricane was opened, and he agreed with opening a counterintelligence investigation based on the FFG information. He told us the decision to open the case was unanimous.

McCabe said the FBI viewed the FFG information in the context of Russian attempts to interfere with the 2016 U.S. elections in the years and months prior, as well as the FBI’s ongoing investigation into the DNC hack by a Russian Intelligence Service (RIS). He also said that when the FBI received the FFG information it was a “tipping point” in terms of opening a counterintelligence investigation regarding Russia’s attempts to influence and interfere with the 2016 U.S. elections because not only was there information that Russia was targeting U.S. political institutions, but now the FBI had received an allegation from a trusted partner that there had been some sort of contact between the Russians and the Trump campaign. McCabe said that he did not recall any discussion about whether the FFG information constituted sufficient predication for opening a Full Investigation, as opposed to a Preliminary Investigation, but said that his belief at the time, based on his experience, was that the FFG information was adequate predication. 167

According to Priestap, he authorized opening the Crossfire Hurricane counterintelligence investigation on July 31, 2016, based upon these discussions. He told us that the FFG information was provided by a trusted source-the FFG–and he therefore felt it “wise to open an investigation to look into” whether someone associated with the Trump campaign may have accepted the reported offer from the Russians. Priestap also told us that the combination of the FFG information and the FBI’s ongoing cyber intrusion investigation of the DNC hacks created a counterintelligence concern that the FBI was “obligated” to investigate. Priestap said that he did not recall any disagreement about the decision to open Crossfire Hurricane, and told us that he was not pressured to open the case.

It includes a discussion explaining why FBI decided against defensive briefings — a key complaint from Republicans. Here’s the explanation Bill Priestap gave.

While the Counterintelligence Division does regularly provide defensive briefings to U.S. government officials or possible soon to be officials, in my experience, we do this when there is no indication, whatsoever, that the person to whom we would brief could be working with the relevant foreign adversary. In other words, we provide defensive briefings when we obtain information indicating a foreign adversary is trying or will try to influence a specific U.S. person, and when there is no indication that the specific U.S. person could be working with the adversary. In regard to the information the [FFG] provided us, we had no indication as to which person in the Trump campaign allegedly received the offer from the Russians. There was no specific U.S. person identified. We also had no indication, whatsoever, that the person affiliated with the Trump campaign had rejected the alleged offer from the Russians. In fact, the information we received indicated that Papadopoulos told the [FFG] he felt confident Mr. Trump would win the election, and Papadopoulos commented that the Clintons had a lot of baggage and that the Trump team had plenty of material to use in its campaign. While Papadopoulos didn’t say where the Trump team had received the “material,” one could reasonably infer that some of the material might have come from the Russians. Had we provided a defensive briefing to someone on the Trump campaign, we would have alerted the campaign to what we were looking into, and, if someone on the campaign was engaged with the Russians, he/she would very likely change his/her tactics and/or otherwise seek to cover-up his/her activities, thereby preventing us from finding the truth. On the other hand, if no one on the Trump campaign was working with the Russians, an investigation could prove that. Because the possibility existed that someone on the Trump campaign could have taken the Russians up on their offer, I thought it wise to open an investigation to look into the situation.

It even explained how, by its read, the investigation met the terms of the DIOG for a Full Investigation.

Under Section 11.B.3 of the AG Guidelines and Section 7 of the DIOG, the FBI may open a Full Investigation if there is an “articulable factual basis” that reasonably indicates one of the following circumstances exists:

- An activity constituting a federal crime or a threat to the national security has or may have occurred, is or may be occurring, or will or may occur and the investigation may obtain information relating to the activity or the involvement or role of an individual, group, or organization in such activity;

- An individual, group, organization, entity, information, property, or activity is or may be a target of attack, victimization, acquisition, infiltration, or recruitment in connection with criminal activity in violation of federal law or a threat to the national security and the investigation may obtain information that would help to protect against such activity or threat; or

- The investigation may obtain foreign intelligence that is responsive to a requirement that the FBI collect positive foreign intelligence-i.e., information relating to the capabilities, intentions, or activities of foreign governments or elements thereof, foreign organizations or foreign persons, or international terrorists.

The DIOG provides examples of information that is sufficient to initiate a Full Investigation, including corroborated information from an intelligence agency stating that an individual is a member of a terrorist group, or a threat to a specific individual or group made on a blog combined with additional information connecting the blogger to a known terrorist group. 45 A Full Investigation may be opened if there is an “articulable factual basis” of possible criminal or national threat activity. When opening a Full Investigation, an FBI employee must certify that an authorized purpose and adequate predication exist; that the investigation is not based solely on the exercise of First Amendment rights or certain characteristics of the subject, such as race, religion, national origin, or ethnicity; and that the investigation is an appropriate use of personnel and financial resources. The factual predication must be documented in an electronic communication (EC) or other form, and the case initiation must be approved by the relevant FBI personnel, which, in most instances, can be a Supervisory Special Agent (SSA) in a field office or at Headquarters. As described in more detail below, if an investigation is designated as a Sensitive Investigative Matter, that designation must appear in the caption or heading of the opening EC, and special approval requirements apply.

Importantly, per Michael Horowitz’s own description of the dispute, this is the topic about which John Durham disagreed. Durham reportedly believed it should have been opened as a Preliminary Investigation — but that would not have changed the investigative techniques available (and there was already a Full Investigation into Carter Page and Paul Manafort).

After first making the same error that Durham did in the Kevin Clinesmith, eleven days after publishing the report, DOJ IG corrected it to note the full implication of Crossfire Hurricane being opened as a counterintelligence investigation, implicating both FARA and 18 USC 951 Foreign Agent charges.

Crossfire Hurricane was opened by CD and was assigned a case number used by the FBI for possible violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), 22 U.S.C. § 611, et seq., and 18 U.S.C. § 951 (Agents of Foreign Governments). 170 As described in Chapter Two, the AG Guidelines recognize that activities subject to investigation as “threats to the national security” may also involve violations or potential violations of federal criminal laws, or may serve important purposes outside the ambit of normal criminal investigation and prosecution by informing national security decisions. Given such potential overlap in subject matter, neither the AG Guidelines nor the DIOG require the FBI to differently label its activities as criminal investigations, national security investigations, or foreign intelligence collections. Rather, the AG Guidelines state that, where an authorized purpose exists, all of the FBI’s legal authorities are available for deployment in all cases to which they apply.

And it provided this short description of why Strzok opened the investigation.

After Priestap authorized the opening of Crossfire Hurricane, Strzok, with input from the OGC Unit Chief, drafted and approved the opening EC. 175 Strzok told us that the case agent normally drafts the opening EC for an investigation, but that Strzok did so for Crossfire Hurricane because a case agent was not yet assigned and there was an immediate need to travel to the European city to interview the FFG officials who had met with Papadopoulos.

Finally, the IG Report provides a description of how the FBI came to open investigations against Trump’s four flunkies, Carter Page, George Papadopoulos, Paul Manafort, and — after a few days — Mike Flynn (though in the process, repeats but did not correct the error of calling this a FARA case).

Strzok, the Intel Section Chief, the Supervisory Intelligence Analyst (Supervisory Intel Analyst), and Case Agent 2 told the OIG that, based on this information, the initial investigative objective of Crossfire Hurricane was to determine which individuals associated with the Trump campaign may have been in a position to have received the alleged offer of assistance from Russia.

After conducting preliminary open source and FBI database inquiries, intelligence analysts on the Crossfire Hurricane team identified three individuals–Carter Page, Paul Manafort, and Michael Flynn–associated with the Trump campaign with either ties to Russia or a history of travel to Russia. On August 10, 2016, the team opened separate counterintelligence FARA cases on Carter Page, Manafort, and Papadopoulos, under code names assigned by the FBI. On August 16, 2016, a counterintelligence FARA case was opened on Flynn under a code name assigned by the FBI. The opening ECs for all four investigations were drafted by either of the two Special Agents assigned to serve as the Case Agents for the investigation (Case Agent 1 or Case Agent 2) and were approved by Strzok, as required by the DIOG. 178 Each case was designated a SIM because the individual subjects were believed to be “prominent in a domestic political campaign. “179

Obviously, the extended account of how the umbrella investigation and individual targeted ones got opened accounts for Strzok’s testimony, but usually relies on someone else where available. That may be because Horowitz walked into this report with a key goal of assessing whether Strzok took any step arising from political bias, and while he concluded that Strzok could not have taken any act based on bias, he ultimately did not conclude one way or another whether he believed Strzok let his hatred for Trump bias his decisions.

But at first, the account made errors about what FBI was really investigating. And even in the longer discussions about how FBI came to predicate the four individual investigations (which follow the cited passage), it doesn’t really explain how FBI decided to go from the umbrella investigation to individualized targets.

Strzok, UNSUB, and his packed bags

So Strzok’s book, as delayed as I think the publication of it is, is in substantial part the first time he gets to explain these early activities.

In a long discussion about how the case got opened, Strzok talks about the difficulties of a counterintelligence investigation, particularly one where you don’t know whom your subject is, as was the case here.

Another reason for secrecy in the FBI’s counterintelligence work is the fundamentally clandestine nature of what it is investigating. Like my work on the illegals in Boston, counterintelligence work frequently has nothing to do with criminal behavior. An espionage investigation, as the Bureau defines it, involves an alleged violation of law. But pure counterintelligence work is often removed from proving that a crime took place and identifying the perpetrator. It’s gaining an understanding of what a foreign intelligence service is doing, who it targets, the methods it uses, and what the national security implications are.

Making those cases even more complicated, agents often don’t even know the subject of a counterintelligence investigation. They have a term for that: an unknown subject, or UNSUB, which they use when an activity is known but the specific person conducting that activity is not — for instance, when they are aware that Russia is working to undermine our electoral system in concert with a presidential campaign but don’t know exactly who at that campaign Russia might be coordinating with or how many people might be involved.

To understand the challenges of an UNSUB case, consider the following three hypothetical scenarios. In one, a Russian source tells his American handler that, while out drinking at an SVR reunion, he learned that a colleague had just been promoted after a breakthrough recruitment of an American intelligence officer in Bangkok. We don’t know the identity of the recruited American — he or she is an UNSUB. A second scenario: a man and a woman out for a morning run in Washington see a figure toss a package over the fence of the Russian embassy and speed off in a four-door maroon sedan. An UNSUB.

Or consider this third scenario: a young foreign policy adviser to an American presidential campaign boasts to one of our allies that the Russians have offered to help his candidate by releasing damaging information about that candidate’s chief political rival. Who actually received the offer of assistance from the Russians? An UNSUB.

The typical approach to investigating UNSUB cases is to open a case into the broad allegation, an umbrella investigation that encompasses everything the FBI knows. The key to UNSUB investigations is to first build a reliable matrix of every element known about the allegation and then identify the universe of individuals who could fit that matrix. That may sound cut-and-dried, but make no mistake: while the methodology is straightforward, it’s rarely easy to identify the UNSUB.

[snip]

The FFG information about Papadopoulos presented us with a text- book UNSUB case. Who received the alleged offer of assistance from the Russians? Was it Papadopoulos? Perhaps, but not necessarily. We didn’t know about his contacts with Mifsud at the time — all we knew was that he had told the allied government that the Russians had dirt on Clinton and Obama and that they wanted to release it in a way that would help Trump.

So how did we determine who else needed to go into our matrix? And what did we know about the various sources of the information? Papadopoulos had allegedly stated it, but it was relayed by a third party. What did we know about both of them: their motivations, for instance, or the quality of their memories? What were the other ways we could determine whether the allegation was true?

And if it was true, how did we get to the bottom of it?

Having laid out the challenge that lay behind the four predications, Strzok then described the circumstances of the trip (with a big gaping hole in the discussion of meeting with the Australians).

He describes how he went home over the weekend, not knowing whether they would leave immediately or after the weekend. That’s why, he explained, he wrote the EC himself, specifically to have one in place before they flew to London.

I quickly briefed him on the facts and asked him to get a bag ready to go to Europe to do some interviews.

When are we leaving? he asked me.

No idea, I told him. Probably not until Monday, but I want to be ready to go tomorrow.

How long are we going for? he asked.

I don’t know, I admitted. A few days at most. I wasn’t sure if we would get to yes with our counterparts, but our sitting there in Europe would make it harder for them to say no.

I had work to do before we could depart. When I left the office on Friday, I grabbed my assigned take-home laptop, configured to operate at a classified level on our secure network.

[snip]

Sitting in my home office, I opened the work laptop and powered it up. The laptops were balky and wildly overpriced, requiring an arcane multi-step process to connect. They constantly dropped their secure connections. Throughout the D.C. suburbs, FBI agents flew into rages when the laptops quit cold while they were trying to work at home. Chinese or Russian intelligence would have been hard-pressed to develop a more infuriating product. Nevertheless, they let you work away from the office.

After logging in, I pulled up a browser and launched Sentinel, our electronic case file system. Selecting the macro for opening an investigation, I filled in the various fields until I reached the blank box for the case name.

They didn’t leave over the weekend, but they did leave on Monday. When they came back, having heard Alexander Downer’s side of the story (probably along with his aide, with whom Papadopoulos met and drank more with on multiple occasions, but that’s not in the book), it seemed a more credible tip.

And in the interim, analysts had found four possible candidates to be the UNSUB.

I was surprised by the amount of information the analysts had already found. Usually, because initial briefings take place at the very beginning of an investigation, they are short on facts and long on conjecture about all the various avenues we might pursue for information. In this case there were already a lot of facts, and several individuals—not just one—had already cropped up in other cases, in other intelligence collection, in other surveillance activity.

Although I was just hours back from Europe, what I saw was deeply dis- concerting. Though we were in the earliest stages of the investigation, our first examination of intelligence had revealed a wide breadth and volume of connections between the Trump campaign and Russia. It was as if we had gone to search for a few rocks only to find ourselves in a field of boulders.

Within a week the team had highlighted several people who stood out as potentially matching the UNSUB who had received the Russian offer of assistance. As we developed information, each person went into the UNSUB matrix, with tick marks next to the matching descriptors.

All this description is surely not going to satisfy Republicans. Nor was it under oath or to law enforcement officers, as Strzok’s other testimony was.

But it’s a compelling description.

It also adds perspective onto the treatment of Mike Flynn. Until they learned about Papadopoulos’ ties with Joseph Mifsud, they still had no clues about who got the tip. Mike Flynn had been eliminated for lack of evidence — but then he picked up a phone and provided the FBI a whole lot of evidence that he could be the guy.

And unless you believe that receiving a credible tip from a close ally that someone is tampering in an election still three months away doesn’t merit urgency, then the other steps all make sense.

I have no idea if that’s why Catherine Herridge got sent to whip out her high-gaslight again. I have no idea whether Nora Dannehy read these excerpts, and in the process realized both the significance of the error in treating this as a FARA investigation, but also how that changes predication into individual subjects.

But there have long been answers to some of the most basic questions that Republicans have returned to over and over again. It’s just that few of the interim investigations ever asked to get those answers. And the one that did — the DOJ IG Report — never even understood the crimes investigated until after the report got published.