Update: And now this, too, has been halted because of the shutdown (h/t Mike Scarcella). This motion suggests the government asked the Internet companies for a stay on Friday. This one suggests the Internet companies asked the government for access to the classified information in the government filing, but the government told them they can’t consider that during the shut-down.

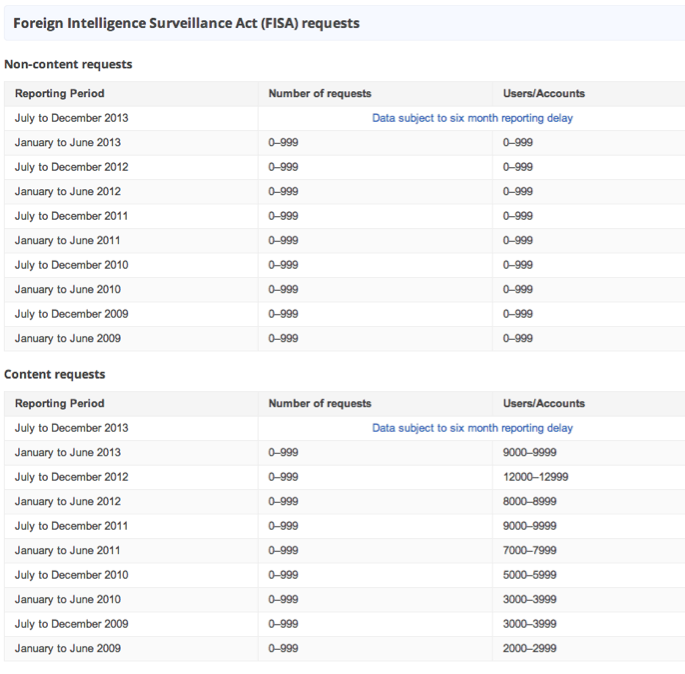

As Time lays out, unlike several of the other NSA-related transparency lawsuits, the fight between the government and some Internet companies (Google, Yahoo, Facebook, Microsoft, and LinkedIn, with Dropbox as amicus) continues even under government shut-down. The government’s brief and declaration opposing the Internet bid for more transparency is now available on the FISA Court docket.

Those documents — along with an evolving understanding of how EO 12333 collection works with FISA collection — raise new questions about the reasons behind the government’s opposition.

When the Internet companies originally demanded the government permit them to provide somewhat detailed numbers on how much information they provide the government, I thought some companies — Google and Yahoo, I imagined — aimed to show they were much less helpful to the government than others, like Microsoft. But, Microsoft joined in, and it has become instead a showdown with Internet companies together challenging the government.

Meanwhile, the phone companies are asking for no such transparency, though one Verizon Exec explicitly accused the Internet companies of grandstanding.

In a media briefing in Tokyo, Stratton, the former chief operating officer of Verizon Wireless, said the company is “compelled” to abide by the law in each country that it operates in, and accused companies such as Microsoft, Google, and Yahoo of playing up to their customers’ indignation at the information contained in the continuing Snowden leak saga.

Stratton said that he appreciated that “consumer-centric IT firms” such as Yahoo, Google, Microsoft needed to “grandstand a bit, and wave their arms and protest loudly so as not to offend the sensibility of their customers.”

“This is a more important issue than that which is generated in a press release. This is a matter of national security.”

Stratton said the larger issue that failed to be addressed in the actions of the companies is of keeping security and liberty in balance.

“There is another question that needs to be kept in the balance, which is a question of civil liberty and the rights of the individual citizen in the context of that broader set of protections that the government seeks to create in its society.”

With that in mind, consider these fascinating details from the government filings.

- The FBI — not the NSA — is named as the classification authority and submits the declaration (from Acting Executive Assistant Director Andrew McCabe) defending the government’s secrecy claims

- The government seems concerned about breaking out metadata numbers from content (or non-content from non-content and content, as Microsoft describes it), even while suggesting this is about providing our “adversaries” hints about how to avoid surveillance

- The government suggests some of what the Internet companies might disclose doesn’t fall under FISC’s jurisdiction

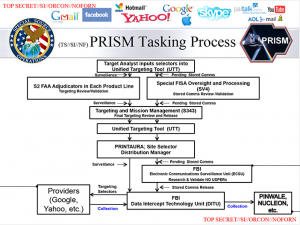

All of these details lead me to suspect (and this is a wildarsed guess) that what the government is really trying to hide here is how they use upstream metadata collection under 12333 to develop relatively pinpointed requests for content from Internet companies. If the Internet companies disclosed that, it would not only make their response seem much more circumscribed than what we’ve learned about PRISM, but more importantly, it would reveal how the upstream, unsupervised collection of metadata off telecom switches serves to target this collection.

The FBI as declarant

Begin with the fact that the FBI — and not NSA or ODNI — is the declarant here. I can think of two possible reasons for this.

One, that much of the collection from Internet companies is done via NSL or another statute for which the FBI, not the NSA, would submit the request. There are a number of references to NSLs in the filings that might support this reading. [Correction: FBI is not required to submit NSLs in all cases, but they are in 18 USC 2709, which applies here.]

It’s also possible, though, that the Internet companies only turn over information if it involves US persons, and that the government gets all other content under EO 12333. As with NSLs, the FBI submits applications specifically for US person data, not the NSA. But if that’s the case, then this might point to massive parallel construction, hiding that much of the US person data they collect comes without FISC supervision.

And remember — the FBI seems to have had the authority to search incidentally collected (presumably, via whatever means) US person data before the NSA asked for such authority in 2011.

There may be other possibilities, but whatever it is, it seems that the FBI would only be the classification authority appropriate to respond here if they are the primary interlocutor with the Internet companies — at least within the context of collection achieved under the FISA Court’s authority.

Breaking out metadata from content numbers and revealing “timing”

While the government makes an argument that revealing provider specific information would help “adversaries” to avoid surveillance, two other issues seem to be of more acute concern.

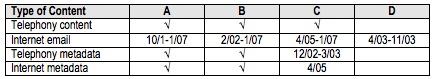

First, it suggests Google and Microsoft’s request to break out requests by FISA provision — and especially Microsoft’s request to “disclose separate categories for ‘non-content’ requests and ‘content and non-content requests” — brought negotiations to a head (see 2-3). This suggests we would see a pretty surprising imbalance there — perhaps (if my theory that the FBI goes to Internet companies only for US person data is correct) primarily specific orders (though that would seem to contradict the PRISM slide that suggested it operated under Section 702). It also suggests that the Internet companies may be providing either primarily content or primarily metadata, not both (as we might expect under PRISM).

The government is also concerned about revealing “the timing of when the Government acquires certain surveillance capabilities.” (see brief 19; the brief references McCabe’s discussion of timing, but the discussion is entirely redacted). That’s interesting because these are to a large extent (though not exclusively) storage companies. It may suggest the government is only asking for data stored in the Internet companies’ servers, not data that is in transit.

The FISC may not have jurisdiction over all this

Then there are hints that the FISC may not have jurisdiction over all the collection involving the Internet companies. That shows up in several ways.

First, in one spot (page 17) the government refers to the subject of its brief as “FISA proceedings and foreign intelligence collection.” In other documents, we’ve seen the government distinguish FISC-governed collection from collection conducted under other authorities — at least EO 12333. Naming both may suggest that part of the jurisdictional issue is that the collection takes place under EO 12333.

There’s another interesting reference to the FISC’s jurisdiction, where the government says it wants to reveal information on the programs “overseen by this Court.”

Although the Government has attempted to release as much information as possible about the intelligence collection activities overseen by this Court, the public debate about surveillance does not give the companies the First Amendment right to disclose information that the Government has determined must remain classified.

I’m increasingly convinced that the government is trying to do a limited hangout with the Edward Snowden leaks, revealing only the stuff authorized by FISC, while refusing to talk about the collection authorized under other statutes (this likely also serves to hide the role of GCHQ). If this passage suggests — as I think it might — that the Government is only attempting to release that information overseen by the FISC, then it suggests that part of what the Internet companies would reveal does not fall under FISC.

Then there are the two additional threats the government uses — in addition to gags tied to FISA orders — to ensure the Internet personnel not reveal this information: nondisclosure agreements and the Espionage Act.

I’m not certain whether the government is arguing whether these two issues — even if formulated in conjunction with FISA Orders — are simply outside the mandate of the FISC, or if it is saying that it uses these threats to gag people engaged in intelligence collection not covered by FISA order gags.

The review and construction of nondisclosure agreements and other prohibitions on disclosure unrelated to FISA or the Courts rules and orders fall far outside the powers that “necessarily result to [this Court] from the nature of [the] institution,” and therefore fall outside the Court’s inherent jurisdiction.

Whichever it is (it could be both), the government seems intent on staving off FISC-mandated transparency by insisting that such transparency on these issues is outside the jurisdiction of the Court.

There there’s this odd detail. Note that McCabe’s declaration is not sworn under oath, but is sworn under penalty of perjury under 18 USC 1746 (see the redaction at the very beginning of the declaration) . Is that another way of saying the FISA Court doesn’t have jurisdiction over this matter? [Update: One possibility is that this is shut-down related–that DOJ’s notaries who validate sworn documents aren’t considered essential.]

The PRISM companies and the poisoned upstream fruit

One more thing to remember. Though we don’t know why, the government had to pay the PRISM companies — that is, the same ones suing for more transparency — lots of money to comply with a series of new orders after John Bates imposed new restrictions on the use of upstream data. I’ve suggested that might be because existing orders were based on poisoned fruit, the illegally collected US person data collected at telecom switches.

That, too, may explain why PRISM company disclosure of the orders they receive would reveal unwanted details about the methods the government uses: there seems to be some relation between this upstream collection and the requests the Internet companies that is particularly sensitive.

As I have repeatedly recalled, back in 2007, these very same Internet companies tried to prevent the telecoms from getting retroactive immunity for their actions under Bush’s illegal wiretap program. That may have been because the telecoms were turning over the Internet companies’ data to the government.

They appear to be doing so again. And this push for transparency seems to be an effort to expose that fact.

Update: Microsoft’s Amended Motion — the one asking to break out orders by statute — raises the initial reports on PRISM, reports on XKeyscore, and on the aftermath of the 2011 upstream problems (which I noted above). It doesn’t talk about any story specifically tying Microsoft to Section 215. However, it lists these statutes among those it’d like to break out.

1These authorities could include electronic surveillance orders, see 50 U.S.C. §§ 1801-1812; phyasical search orders, see 50 U.S.C. §§ 1821-1829; pen register and trap and trace orders, see 50 U.S.C. §§ 1841-1846; business records orders, see 50 U.S.C. §§ 1861-1862; and orders and directives targeting certain persons outside the United States, see 50 U.S.C. §§ 1881-1881g. [my emphasis]

If I’m not mistaken, the motion doesn’t reference this article, which described how the government accessed Skype and Outlook, which you’d think would be one of the ones MSFT would most want to refute, if it could. But I’ve also been insisting that they must get Skype info for the phone dragnet, otherwise they couldn’t very well claim to have the whole “phone” haystack.

But the mention of Section 215 suggests they may be included in that order.

Also, we keep seeing physical search orders included in a communication arena. I wonder if that’s a storage issue.

Update: One more note about the MSFT Amended Motion. It lists where the people involved got their TS security clearances. MSFT’s General Counsels is tied to DOD; the lawyers on the brief all are tied to FBI.

One final detail on MSFT. Though the government brief doesn’t say this, MSFT is also looking to release the number of accounts affected by various orders, not just the number of targets (which is what the government wants to release). That’s a huge difference.

![[NSA presentation, PRISM collection dates, via Washington Post]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/WaPo_Prism-Slide5_06JUN2013_300pxw.jpg)

![[graphic: Google Finance]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Graph_MSFT_10-YrChart_18JUL2013_500pxw1.jpg)