Tragic Loss in Pakistan: Parveen Rehman Gunned Down

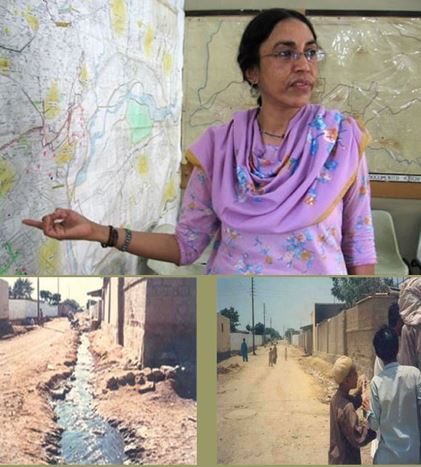

Parveen Rehman as she appeared in NPR’s story about her, top, and a before and after set of photos from installation of a sewer line from the Orangi Pilot Project website, bottom.

Around the middle of the day my time yesterday, my Twitter feed exploded in rage with tweets from Pakistan bemoaning a great loss. Killings in Karachi have become disturbingly commonplace of late (although this killing doesn’t fit the sectarian nature of many of the current ones), but one killing Wednesday provoked outrage at a level I have never seen before from a number of Pakistanis I follow.

A look at the life of Parveen Rehman and the Orangi Pilot Project she headed justifies the outrage at her murder and shows the depth of the loss that has been suffered. From a report in The Nation, it appears that Rehman was targeted specifically:

Renowned social worker and Director of Slum Rehabilitation Project known as Orangi Pilot Project, Parveen Rehman, was gunned down on Wednesday in an incident of target killing within the precincts of Pirabad police station.

Parveen Rehman currently working as Director of Orangi Pilot Project founded by Akhter Hamid Khan was shot dead when she was on her way home from Orangi Town.

DIG Javaid Odho, when contacted, told TheNation that the gunmen riding a motorbike targeted her near Abdullah College. Assailants managed to flee from the scene while she was taken to Abbasi Shaheed Hospital where the doctors pronounced her dead, DIG Odho added.

He further said that assailants targeted her specifically and did not harm the driver.

The Orangi Pilot Project, which Rehman headed, is a remarkable example of people banding together to help one another when they belong to impoverished groups that government will not help. From their website:

Provision of a housing unit is not a problem. People build their houses incrementally, with building component manufacturing yards in the settlements providing building materials and components on credit. Initially the land supplier (who is a resourceful person having links with politicians, government departments and the private operators) arranges the supply of water through water tankers and transportation (i.e. bus routes). As the settlement expands and consolidates, need for water supply, sewage disposal, schools and clinics arises. For livelihood, people set up micro enterprises in their homes. People lobby with government for facilities but due to lack of or adhoc+ government response, they soon undertake self help initiatives.

In 1980 when OPP started work in Orangi, it observed peoples initiatives in provision of sewage disposal, water supply, schools and clinics, as well as the limitations of the response from the government. OPP decided to strengthen people’s initiatives with social and technical guidance.

It is demonstrated through the programs that at the neighborhood level people can finance, manage and maintain facilities like sewerage, water supply, schools, clinics, solid waste disposal and security. Government’s role is to compliment people’s work with larger facilities like trunk sewers and treatment plants, water mains and water, colleges/universities, hospitals, main solid waste disposals and land fill sites.

The component-sharing concept clearly shows that where government partners with the people, sustainable development can be managed through local resources.

The OPP has been fantastically successful, helping to provide critical infrastructure for over two million people:

The model that has evolved from the program is the component-sharing concept of development with people and government as partners. It has evolved from a lane to the city/town. The program has extended to all of Orangi town (where 106,726 houses, have invested Rs. 122.61 million in secondary, lane sewers and sanitary latrines, with govt. investing Rs. 739.3 million on main disposals) and to 463 settlements in Karachi and 44 cities/ towns, also in 93 villages (spread mostly over the Sindh and Punjab Provinces) covering a population of more than 2 million.

Back in 2008, NPR profiled Rehman:

Dealing with government officials initially was difficult for women, Rehman says. If women told an official, ” ‘You do this, you do that’ … he would start avoiding us. There’s a lot of things he can’t do. The system is such. But now we go and we say, ‘We want your advice. Please tell us what to do,’ and they feel very happy.

“I feel sometimes — not with men and women — with any group, if you come just upfront and try to be … the person taking credit for everything, that’s where things start going wrong,” she says. Once you rise up horizontally, you take everybody with you. But if you want to rise vertically, you will rise, but then nobody will be there for you.”

Rehman’s horizontal approach clearly has had a profound effect, as group outrage spread quickly with word of her murder.

The OPP works in a number of areas beyond its initial roots in the development of sewer systems, including a microfinance program that operates at a cost of only 7.9% of the capital lent as compared to the report of 10% by Muhammad Yunus’ Grameen Development Bank for which Yunus won a Nobel Prize.

Rehman has already been laid to rest, and the Express Tribune reports that a range of public figures attended her funeral:

Her funeral prayer was held at Gulistan-e-Jauhar, outside her residence and was attended by people belonging to various non-governmental organisations, members of the civil society and trade unions.

Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz leader Nehal Hashmi, Muttahida Qaumi Movement Rabta Committee member Khwaja Izharul Hassan, Managing Director Karachi Water and Sewerage Board Misbahuddin and a number of other noted figures also attended the funeral.

The murder shocked Rehman’s colleagues who said she did not have any personal enmity and worked mostly on projects for the uplift of the poor areas.

Considering Rehman’s operating style of not wanting to take “credit for everything” (the OPP website lacks the customary “About Us” type of page where the organization’s senior management is profiled), it seems likely the organization will be capable of carrying on its essential work without her, but her loss is profound and no doubt will be felt for years to come.