DC Circuit: Go Big and [in a Footnote] Go Blassingame!

Note: Our discussion of the decision starts after 10 minutes.

During the entire month we’ve been waiting for a DC Circuit ruling on Trump’s immunity claim, I have argued we’d be better off with an opinion for which SCOTUS was likely to deny cert than a decision in which a — say — Judge Karen Henderson concurrence offered surface area for Justices to claw out review.

Before I explain why there’s a good shot that this opinion was worth the wait, let me review how SCOTUS came to uphold a Judge Chutkan opinion chipping away at Trump’s Executive Privilege claims for January 6. In that case, Trump was trying to prevent the Archives from sharing presidential documents with the January 6 Committee; because he was seeking to prevent something, it was actually easier to make appeals go faster. The appeals were resolved in 74 days:

- On November 9, 2021, Judge Chutkan rejected Trump’s attempt to enjoin the Archives from sharing his papers

- On November 30, a DC Circuit panel of three Democratic appointees heard his case; on December 9, the Circuit issued an opinion from Patricia Millet upholding Judge Chutkan

- On January 22, 2022, with only a dissent from Clarence Thomas, SCOTUS upheld the DC Circuit opinion; Justice Kavanaugh noted that, even if a more stringent standard were applied, Trump’s claim would still fail

This appeal has taken 67 days thus far:

- On December 1, Judge Chutkan, waiting less than 12 hours after the long-delayed issuance of an opinion in Blassingame holding that former Presidents are not immune from lawsuit when in the role of office-seeker, issued her ruling rejecting Trump’s immunity claim

- A bipartisan panel — Karen Henderson, Florence Pan, and Michelle Childs — heard Trump’s appeal on January 9

- The panel issued a strong per curiam opinion on February 6

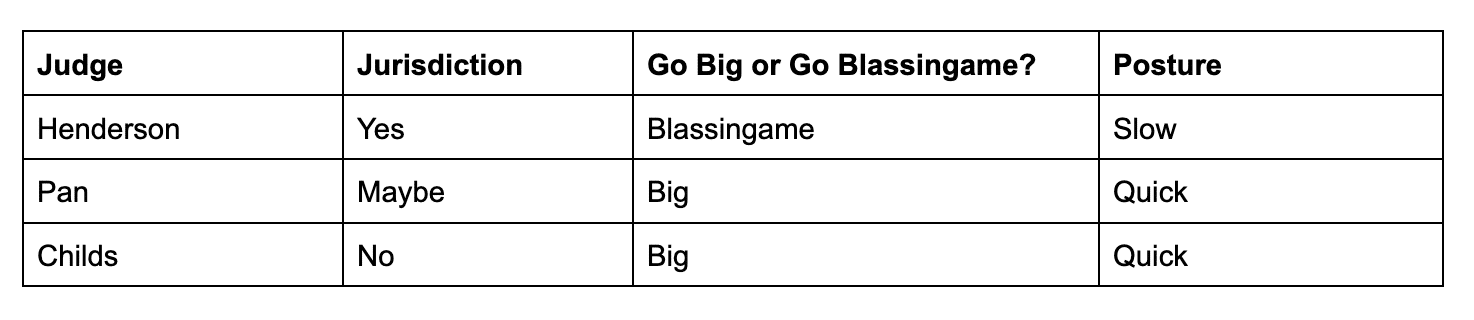

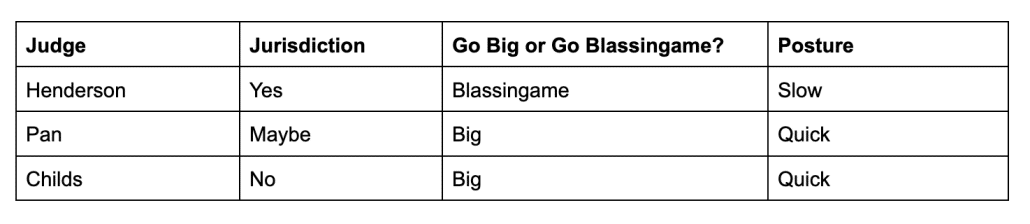

In recent weeks, I had shown where there seemed to be disagreement on that panel, disagreements that are all resolved in the opinion.

Posture

Let’s start with the last one, what I called posture. Judge Henderson had originally not favored an expedited review. This order forces Trump into an expedited appeals process.

The Clerk is directed to withhold issuance of the mandate through February 12, 2024. If, within that period, Appellant notifies the Clerk in writing that he has filed an application with the Supreme Court for a stay of the mandate pending the filing of a petition for a writ of certiorari, the Clerk is directed to withhold issuance of the mandate pending the Supreme Court’s final disposition of the application. The filing of a petition for rehearing or rehearing en banc will not result in any withholding of the mandate, although the grant of rehearing or rehearing en banc would result in a recall of the mandate if the mandate has already issued.

The only way he can stop Judge Chutkan from issuing opinions on the remaining motions to dismiss filed last fall is if he immediately appeals to SCOTUS for a stay pending appeal, which he has already said he’d done. The only way he can get that stay is if five Justices say they think Trump will succeed on the merits and vote to grant the stay.

Steve Vladeck says that SCOTUS has a lot of options, but the two most likely are to deny the stay or to grant an appeal in this term, committing to an opinion by June.

Jurisdiction

At least by my read in the table, the one reason Pan and Childs couldn’t write their own opinion without Henderson was because Childs was much more cautious about whether the Circuit even had jurisdiction.

Nine pages of the opinion treat that question. It adopts two suggestions from Jack Smith’s prosecutor James Pearce. Most notably, it notes that SCOTUS has repeatedly given [former] Presidents get immediate appeals.

Nor was the question presented in Midland Asphalt anything like the one before us. Procedural rules are worlds different from a former President’s asserted immunity from federal criminal liability. The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that the President is sui generis. In the civil context, the Court has held that the denial of the President’s assertion of absolute immunity is immediately appealable “[i]n light of the special solicitude due to claims alleging a threatened breach of essential Presidential prerogatives under the separation of powers.” Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. at 743. And in United States v. Nixon, the Court waived the typical requirement that the President risk contempt before appealing because it would be “unseemly” to require the President to do so “merely to trigger the procedural mechanism for review of the ruling.” 418 U.S. 683, 691–92 (1974). It would be equally “unseemly” for us to require that former President Trump first be tried in order to secure review of his immunity claim after final judgment.

Trump did not contest jurisdiction here, so it’s unlikely to be something that SCOTUS pursues (and if they did, then it would get bumped back to Chutkan for trial).

Go Big and [in a Footnote] Go Blassingame

Finally, I noted that Judge Henderson seemed to have concerns about the scope of their decision — what she described “floodgates” of follow-on charges. She at least considered the wisdom of limiting this opinion to a former President’s unofficial acts — in this case, defined as those of an office-seeker under Blassingame.

Rather than going Blassingame, though, the panel’s top line holding went Big.

The operative language in this opinion rejects the notion of Presidential immunity categorically as a violation of separation of powers.

At bottom, former President Trump’s stance would collapse our system of separated powers by placing the President beyond the reach of all three Branches. Presidential immunity against federal indictment would mean that, as to the President, the Congress could not legislate, the Executive could not prosecute and the Judiciary could not review. We cannot accept that the office of the Presidency places its former occupants above the law for all time thereafter. Careful evaluation of these concerns leads us to conclude that there is no functional justification for immunizing former Presidents from federal prosecution in general or for immunizing former President Trump from the specific charges in the Indictment. In so holding, we act, “not in derogation of the separation of powers, but to maintain their proper balance.” See Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. at 754. [my emphasis]

Even in that sweeping language, though, the opinion addresses the question of presidential immunity generally and specifically, as to the charges in the indictment.

The import of this move in resolving any disagreement on the panel is more clear elsewhere.

Perhaps most importantly, footnote 14, does something that Judge Chutkan also did. It said that because they reject the notion of categorical immunity, they don’t have to review whether the alleged crimes are official acts.

14 Because we conclude that former President Trump is not entitled to categorical immunity from criminal liability for assertedly “official” acts, it is unnecessary to explore whether executive immunity, if it applied here, would encompass his expansive definition of “official acts.” Nevertheless, we observe that his position appears to conflict with our recent decision in Blassingame, 87 F.4th at 1. According to the former President, any actions he took in his role as President should be considered “official,” including all the conduct alleged in the Indictment. Appellant’s Br. 41–42. But in Blassingame, taking the plaintiff’s allegations as true, we held that a President’s “actions constituting re-election campaign activity” are not “official” and can form the basis for civil liability. 87 F.4th at 17. In other words, if a President who is running for re-election acts “as office-seeker, not office-holder,” he is not immune even from civil suits. Id. at 4 (emphasis in original). Because the President has no official role in the certification of the Electoral College vote, much of the misconduct alleged in the Indictment reasonably can be viewed as that of an office-seeker — including allegedly organizing alternative slates of electors and attempting to pressure the Vice President and Members of the Congress to accept those electors in the certification proceeding. It is thus doubtful that “all five types of conduct alleged in the indictment constitute official acts.” Appellant’s Br. 42. [my empahsis]

But they say if they did have to review whether the indictment charged Trump for official acts, the fact that so many of the alleged acts in the indictment pertain to Trump’s role as an office-seeker, and because Presidents have no role in election certifications, the indictment would survive that more particular review anyway.

This is the kind of out that Justice Kavanaugh took on a related issue, whether the interests of Congress in reviewing an attack on the election certification preempted any Executive Privilege claims.

That is, both the District and Circuit have already said that, if they were asked to consider whether this indictment withstands an immunity claim, it substantially would.

I have no idea what SCOTUS will do. But by producing a unanimous opinion with little surface area for Justices to grab hold, Judges Henderson, Pan, and Childs may have ended up producing the most expeditious result.