To Celebrate Its Third Birthday, the Durham Investigation Will Attempt to Breach Eric Lichtblau’s Reporter’s Privilege

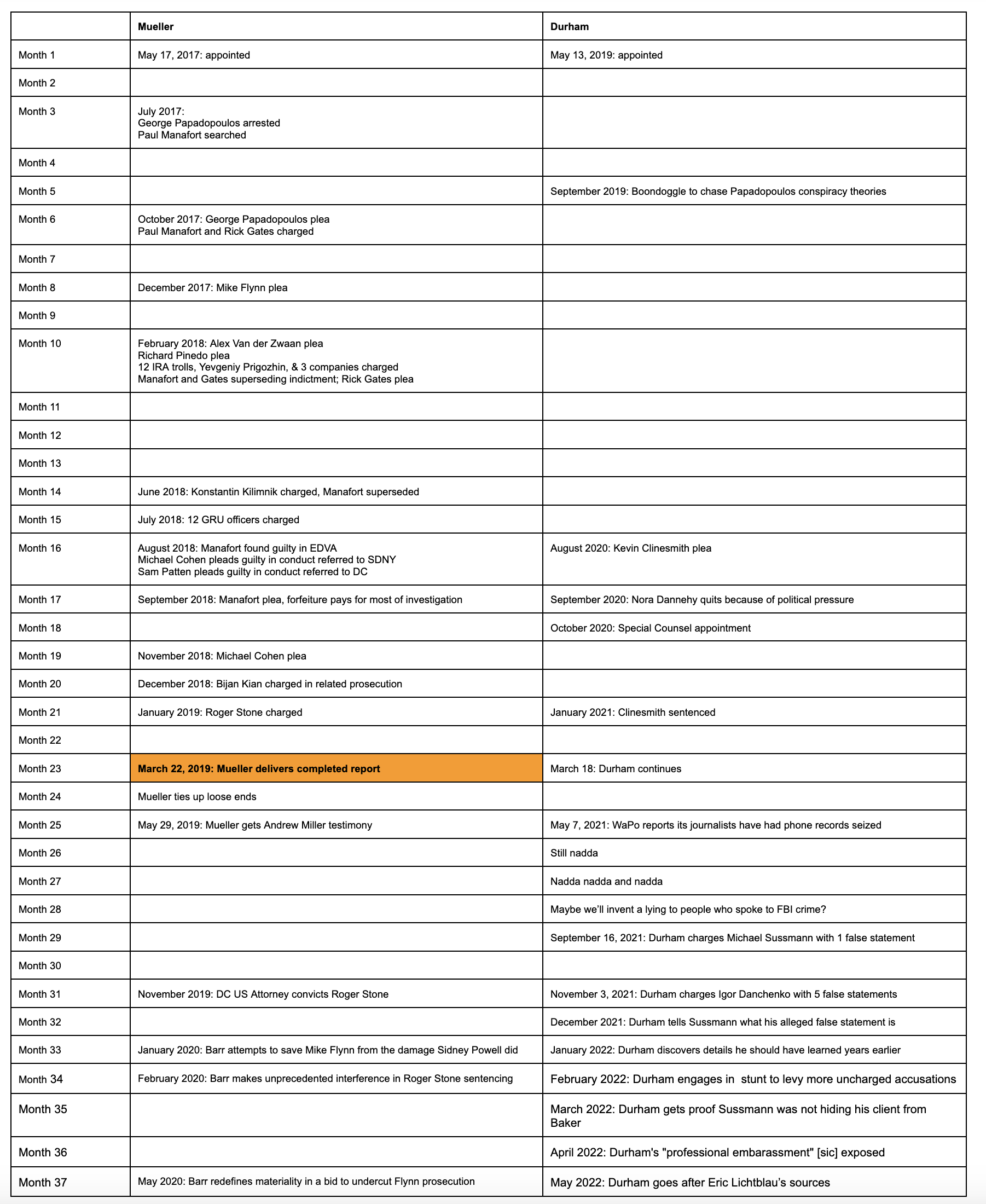

Happy Birthday to Johnny D and his merry band of prosecutors! Today marks your third birthday! Quite a milestone for an investigation that has just one conviction — a gift wrapped up with a bow from Michael Horowitz — to show for those three years.

John Durham, however, had something much more ambitious planned to mark the milestone, it appears.

As Sean Berkowitz noted earlier this week, Sussmann’s team wants to call Eric Lichtblau as a witness in next week’s trial. They were able to get Lichtblau to agree to testify based on the understanding he would only testify about conversations with Michael Sussmann and Rodney Joffe. But Durham’s team — I guess to assert the newfound brattiness of a three-year-old — refused to limit their cross-examination to those who had waived confidentiality.

There is an issue here that I want to alert you to. We reached out to Mr. Lichtblau’s counsel, actually counsel for The New York Times, to explore their willingness in light of the First Amendment issues to testify at the trial. And we told him that both Mr. Sussmann and Mr. Joffe would waive any privilege associated with the press privilege; and that gave The New York Times comfort that, notwithstanding their normal policy of objecting, they would allow him to testify about his interactions with

Mr. Sussmann and Mr. Joffe, communications between the two as well as communications with the FBI that wouldn’t be protected by privilege because the FBI reached out to them to ask them to hold the story.

They did tell us that they would object to questioning Mr. Lichtblau about independent research he did in support of the story, you know, people he spoke with to verify sources and other types of things that were not communicated to Mr. Sussmann.

We told him from our perspective that seemed like a fair line to draw, and we would not get into that.

He’s reached out to the Government on that issue, and it appears there may be — again, I don’t want to speak for the Government — but it appears that they may not be in a position today to give The New York Times that assurance. And so we expect The New York Times sometime this week will be filing a motion on that issue to tee it up for your Honor.

I know you’re welcoming all this additional paper.

THE COURT: One more intervenor in the mix.

MR. BERKOWITZ: “All the news that’s fit to print.”

As a motion submitted by Lichtblau yesterday and a declaration from his lawyer Chad Bowman lays out, after Sussmann and Rodney Joffe waived their confidentiality with Lichtblau by April 21, Durham then took eleven days to consider whether they were willing to limit Lichtblau’s testimony to his conversations with the two of them. Predictably, Andrew DeFilippis was not.

On April 21, 2022, I spoke by telephone with Andrew DeFilippis in the Special Counsel’s Office, as well as several of his colleagues. I asked whether the prosecution similarly would be willing to limit examination to direct communications between Mr. Sussmann and Mr. Lichtblau, a journalist, particularly given the Department of Justice’s new policy restricting the use of compulsory process to obtain information from reporters, as memorialized in the Office of the Attorney General’s July 21, 2021 Memorandum, a true and correct copy of which is attached as Exhibit B and which is also available online at at https://www.justice.gov/ag/page/file/1413001/download. Mr. DeFilippis stated that the prosecution needed time to consider the request.

On May 2, 2022, during a follow-up telephone call, Mr. DeFilippis stated that the prosecution was unable to give “any assurance” that their cross-examination questioning of Mr. Lichtblau would be confined to his discussions with Mr. Sussmann. In particular, Mr. DeFilippis stated that certain of Mr. Lichtblau’s email communications with third parties were within the prosecutions possession, and that the prosecution might want to examine Mr. Lichtblau about other, unknown aspects of his reporting. He also indicated a view that any reporter’s privilege would be pierced by a trial subpoena.

This is, by all appearances, a naked attempt to keep a very devastating witness off the stand. There’s no way, even under prior guidelines, Durham would have been able to get Lichtblau’s testimony; particularly given that they’ve got the communications in question, they couldn’t show a need to get his testimony.

That’s all the more true given Merrick Garland’s prohibition on requiring testimony from reporters.

But Lichtblau’s testimony is pretty critical for Sussmann, not least because he’ll make it clear he reached out to Sussmann and that the interest in reporting on Russian hacking was in no way tied to animus towards Trump. Plus, he would explain what an impact that acceding to the request from FBI to hold the story was for his career.

Durham has long tried to hide that after the FBI requested, Sussmann and Joffe acceded to help kill the story. It kills his conspiracy theory. It corroborates Sussmann’s stated motivation for sharing the DNS anomaly, that he was trying to help the FBI. Particularly given that both Sussmann and Joffe have Fifth Amendment reasons not to want to testify, Lichtblau would provide a way to get the full extent of that process into the trial.

But Durham wants to prevent it from coming into evidence unless Lichtblau is willing to pay a needless price for doing so.