Raez Qadir Khan: Hoisting the FBI on Its Own Metadata Problems

As I said earlier, the lawyers defending Pakistani-American Raez Qadir Khan — who is accused of material support of terrorist training leading up to an associate’s May 2009 attack on the ISI in Pakistan — are doing some very interesting things with the discovery they’ve gotten.

Request for Surveillance Authorities

The first thing they did, in a July 14, 2014 filing, was to list all the kinds of surveillance they’ve been shown in discovery with a list of possible authorities that might be used to conduct that surveillance. The motion is an effort to require the government to describe what it got how.

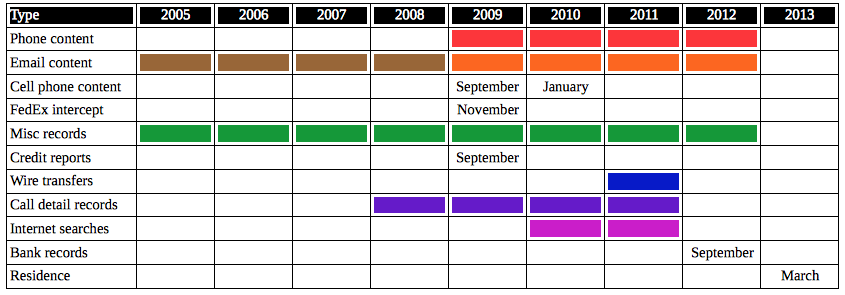

The table above is my summary of what the motion reveals and shows only if a particular kind of surveillance happened during a given year; it only gives more specific dates for one-time events.

The brown (orange going dark!) reflects that emails were turned over in discovery from this period, but that the 2013 search warrant apparently says “authorization to collect emails existed from August 2009 to May 2012.” That’s not necessarily damning; they could get those earlier emails legitimately via a number of avenues that don’t involve “collecting” them. But it is worth noting for reasons I explain below.

The filing itself includes tables with more specific dates, Bates numbers, possible authorities, and — where relevant — search warrant items reliant on the items in question. It also describes surveillance they know to have occurred — further Internet and email surveillance, for example, a 2009 search of Khan’s apartment, as well as surveillance in later 2012 — that was not turned over in discovery.

Effectively, the motion lays out all the possible authorities that might be used to collect this data and then makes very visible that the criminal search warrant was derivative of it (there’s a bit of a problem, because the warranted March 2013 search actually took place after the indictment, and so Khan’s indictment can’t be entirely derivative of this stuff; that relies largely on emails).

I also think some of the authorities may not be comprehensive; for example, the pre-2009 emails may have been a physical FISA search. We also know FISC has permitted the government to collect URL searches under Section 215.

But it’s a damn good summary of the multiple authorities the government might use to obtain such information, by itself a superb demonstration of the many ways the government can obtain and parallel construct evidence.

The filing seems to suggest that the investigation started in fall 2009, some months after Khan’s alleged co-conspirator, Ali Jalil, carried out a May 2009 suicide attack in Pakistan. If that’s right, then the government obtained miscellaneous records (which is not at all surprising; these are things like immigration and PayPal records), email content, and call detail records retroactively. Alternately (Jalil was arrested in the Maldives in April 2006 and interrogated by people presenting themselves as FBI), the government conducted all the other surveillance back to 2005 in real time, but doesn’t want to show Khan’s team it has. In a response to this motion, the government claims that when the surveillance of Khan began is classified.

The motion for a description of which authorities the government used to obtain particular information is still pending.

Motion to Throw Out the Emails

Here’s where things get interesting.

On September 15, Khan’s lawyers submitted a filing moving to throw out all the email evidence (which is the bulk of what has been shown so far and — as I said — most of what the indictment relies on). It argues the 504 emails provided in discovery — spanning from February 2005 to February 2012–lack much of the metadata detail necessary to be submitted as authenticated evidence. Some of the problems, but by no means all, stem from FBI having printed out the emails, hand-redacted them, then scanned them and sent them as “electronic production” to Khan’s lawyers.

That argument is highly unlikely to get anywhere on its own, though a declaration from a forensics expert does raise real questions about the inconsistency of the metadata provided in discovery.

But the filing does pose interesting questions that — in conjunction with questions about the authorities used to investigate Khan — may be more fruitful.