The Government Doesn’t Want to Talk about Collecting Domestic Communications under FAA

On Friday, the government appealed the 2nd Circuit’s decision that Amnesty International and other NGOs and individuals have standing to challenge the FISA Amendments Act. I’ll have a post on the implications of their substantive argument shortly. But in the meantime, I wanted to note what they’re not even addressing.

On Friday, the government appealed the 2nd Circuit’s decision that Amnesty International and other NGOs and individuals have standing to challenge the FISA Amendments Act. I’ll have a post on the implications of their substantive argument shortly. But in the meantime, I wanted to note what they’re not even addressing.

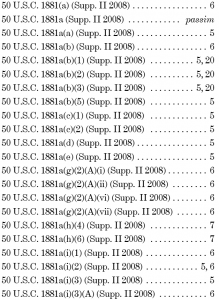

The image to the left is a fragment of the government’s references to statutes and regulation mentioned in its brief; it’s the part of the list referring to the part of the FAA in question. As you can see, it almost–but not quite–lists every clause of the law.

One clause notably missing from the almost-sequential list above is 1881a(b)(4), which reads,

[An acquisition authorized under subsection (a)] may not intentionally acquire any communication as to which the sender and all intended recipients are known at the time of the acquisition to be located in the United States;

And while it mentions clauses that refer back to this restriction (for example, 1881a(c)(1), 1881a(d), 1881a(g)(2)(A)(i), etc), it never goes back and includes this language–the requirement that the government not intentionally acquire communications that are located entirely within the US–in its argument. (There are other clauses the brief ignores, a number of which pertain to oversight of the certifications the government has made; I may return to these at a future time.)

Or, to put it another way, the government never admits that the FAA permits the purportedly unintentional collection of entirely domestic communication.

And yet that is a part of this lawsuit. The original complaint in this suit invoked this clause:

An acquisition under section 702(a) may not … “intentionally acquire any communication as to which the sender and all intended recipients are known at the time of the acquisition to be located in the United States

[snip]

Moreover, the Attorney General and the DNI may acquire purely domestic communications as long as there is uncertainly about the location of one party to the communications.

And the 2nd Circuit opinion (authored by Gerard Lynch) referenced this clause:

“Targeting procedures” are procedures designed to ensure that an authorized acquisition is “limited to targeting persons reasonably believed to be located outside the United States,” and is designed to “prevent the intentional acquisition of any communication as to which the sender and all intended recipients are known at the time of the acquisition to be located in the United States.”

[snip]

In addition, the certification must attest that the surveillance complies with statutory limitations providing that it:

[snip]

(4) may not intentionally acquire any communication as to which the sender and all intended recipients are known at the time of the acquisition to be located in the United States;

[snip]

Under the FAA, in contrast to the preexisting FISA scheme, the FISC may not monitor compliance with the targeting and minimization procedures on an ongoing basis. Instead, that duty falls to the AG and DNI, who must submit their assessments to the FISC, as well as the congressional intelligence committees and the Senate and House Judiciary Committees.

[snip]

But the government has not asserted, and the statute does not clearly state, that the FISC may rely on these assessments to revoke earlier surveillance authorizations.

Now, to some degree, the government might argue it ignored the clause prohibiting intentional–but not accidental–targeting of domestic communications because the plaintiffs’ primary basis for establishing standing is their frequent communication with likely targets overseas. As I’ll show, the government wants to make this case about a particular definition of a target, and key to that argument is a claim that it is impossible for the plaintiffs to be targets.

Yet therein lies one of the key problems with their argument, given that 1881a(b)(4) only prohibits the plaintiffs from being intentional targets; the FAA very pointedly did not prohibit the government from keeping US person information it “unintentionally” collected. In fact, Mike McConnell and Michael Mukasey started issuing veto threats when Russ Feingold tried to restrict the ongoing use of domestic communications identified as such after the fact.

Finally, in the one case that approved this kind of collection (though under the Protect America Act, not the FAA) used targeting procedures to substitute for particularity required under the Fourth Amendment. Under PAA, those procedures were not mapped out by law; under FAA they are, partly in the clause the government wants to ignore.

And yet, remarkably, the government doesn’t want that clause to be part of its discussion with SCOTUS. Seeing as how even the FISA Court of Review finds that substitute for particularity–the targeting procedures–to be a key part of compliance with the Fourth Amendment, you’d think that would be relevant.