Before I do a deep dive of the 302 that Billy Barr had released in yet another attempt to blow up the Mike Flynn prosecution, let me review the conclusion of the Mueller Report was with regards to whether President Trump even knew about Mike Flynn’s calls with Sergey Kislyak, much less ordered them.

Some evidence suggests that the President knew about the existence and content of Flynn’s calls when they occurred, but the evidence is inconclusive and could not be relied upon to establish the President’s knowledge.

[snip]

Our investigation accordingly did not produce evidence that established that the President knew about Flynn’s discussions of sanctions before the Department of Justice notified the White House of those discussions in late January 2017.

The conclusion is central to the finding that there was no proof of a quid pro quo. If Trump had ordered Flynn to undermine sanctions — as a sentencing memo approved by Main DOJ explained — it would have been proof of coordination.

The defendant’s false statements to the FBI were significant. When it interviewed the defendant, the FBI did not know the totality of what had occurred between the defendant and the Russians. Any effort to undermine the recently imposed sanctions, which were enacted to punish the Russian government for interfering in the 2016 election, could have been evidence of links or coordination between the Trump Campaign and Russia. Accordingly, determining the extent of the defendant’s actions, why the defendant took such actions, and at whose direction he took those actions, were critical to the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation.

That means the conclusion adopted by the Mueller Report is precisely the one that the FBI Agent who investigated Flynn, William Barnett, held, as described repeatedly in the interview done by Jeffrey Jensen in an attempt to undermine the Mueller prosecution.

With respect to FLYNN’s [redacted] with the Russian Ambassador in December 2016, BARNETT did not believe FLYNN was being directed by TRUMP.

The Mueller Report reached that conclusion in spite of the fact that — as Barnett describes it — in his second interview, Flynn said that Trump was aware of the calls between him and the Russian Ambassador.

During one interview of FLYNN, possibly the second interview, one of the interviewers asked a series of questions including one which FLYNN’s answer seemed to indicate TRUMP was aware of [redacted] between FLYNN and the Russian Ambassador. BARNETT believed FLYNN’s answer was an effort to tell the interviewers what they wanted to hear. BARNETT had to ask the clarifying question of FLYNN who then said clearly that TRUMP was not aware of [redacted]

Barnett then goes on a paragraph long rant claiming there was no evidence that Trump was aware.

BARNETT said numerous attempts were made to obtain evidence that TRUMP directed FLYNN concerning [redacted] with no such evidence being obtained. BARNETT said it was just an assumption, just “astro projection,” and the “ground just kept being retreaded.”

The claim that there was no evidence that Trump directed Flynn to undermine sanctions is false. I say that because Flynn himself told Kislyak that Trump was aware of his conversations with Kislyak on December 31, 2016, when Kislyak called up to let Flynn know that Putin had changed his mind on retaliation based on his call.

FLYNN: and, you know, we are not going to agree on everything, you know that, but, but I think that we have a lot of things in common. A lot. And we have to figure out how, how to achieve those things, you know and, and be smart about it and, uh, uh, keep the temperature down globally, as well as not just, you know, here, here in the United States and also over in, in Russia.

KISLYAK: yeah.

FLYNN: But globally l want to keep the temperature down and we can do this ifwe are smart about it.

KISLYAK: You’re absolutely right.

FLYNN: I haven’t gotten, I haven’t gotten a, uh, confirmation on the, on the, uh, secure VTC yet, but the, but the boss is aware and so please convey that. [my emphasis]

Flynn literally told the Russian Ambassador that Trump was aware of the discussions, but Barnett claims there was no evidence.

Now is probably a good time to note that, months ago, I learned that Barnett sent pro-Trump texts on his FBI phone, the mirror image of Peter Strzok sending anti-Trump texts.

So Billy Barr has released a 302 completed just a week ago, without yet releasing the Bill Priestap 302 debunking some of the earlier claims released by Billy Barr in an attempt to justify blowing up the Flynn prosecution, much less the 302s that show that Flynn appeared to lie in his first interview with Mueller’s investigators (as well as 302s showing that KT McFarland coordinated the same story).

And the 302 is an ever-loving shit show. Besides the key evidence — that his claim that investigators didn’t listen to him even though the conclusion of the Mueller Report is the one that he says only he had — Barnett disproves his claims over and over in this interview.

Barnett’s testimony substantially shows five things:

- He thought there was no merit to any suspicions that Flynn might have ties to Russia

- He nevertheless provided abundant testimony that some of the claims about the investigation (specifically that Peter Strzok and probably Brandon Van Grack had it in for Flynn) are false

- Barnett buries key evidence: he mentions neither that Flynn was publicly lying about his conversations with Sergey Kislyak (which every other witness said was driving the investigation), and he did not mention that once FBI obtained call records, they showed that Flynn had lied to hide that he had consulted with Mar-a-Lago before he called Sergey Kislyak

- Jensen didn’t ask some of the most basic questions, such as whether Barnett thought he had to investigate further after finding the Kislyak call or who the multiple people Barnett claimed joked about wiping their phone were

- Barnett believes that Mueller’s lawyers (particularly Jeannie Rhee and Andrew Weissmann) were biased and pushing for a conclusion that the Mueller Report shows they didn’t conclude, but he didn’t work primarily with either one of them and his proffered evidence against Rhee actually shows the opposite

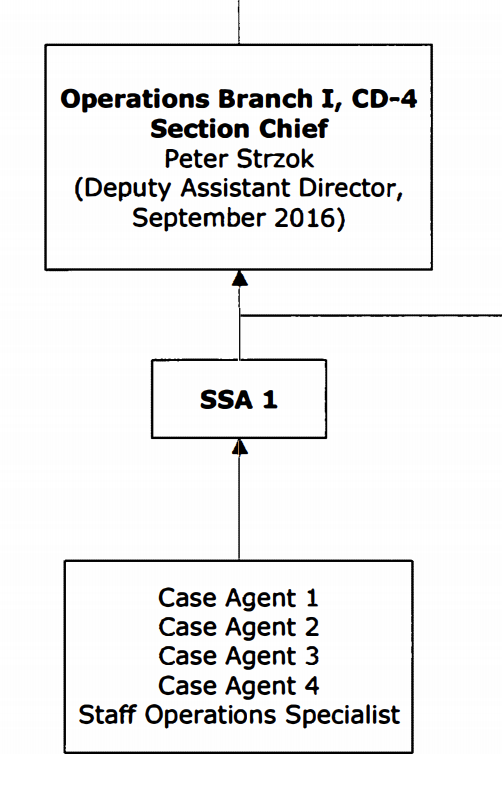

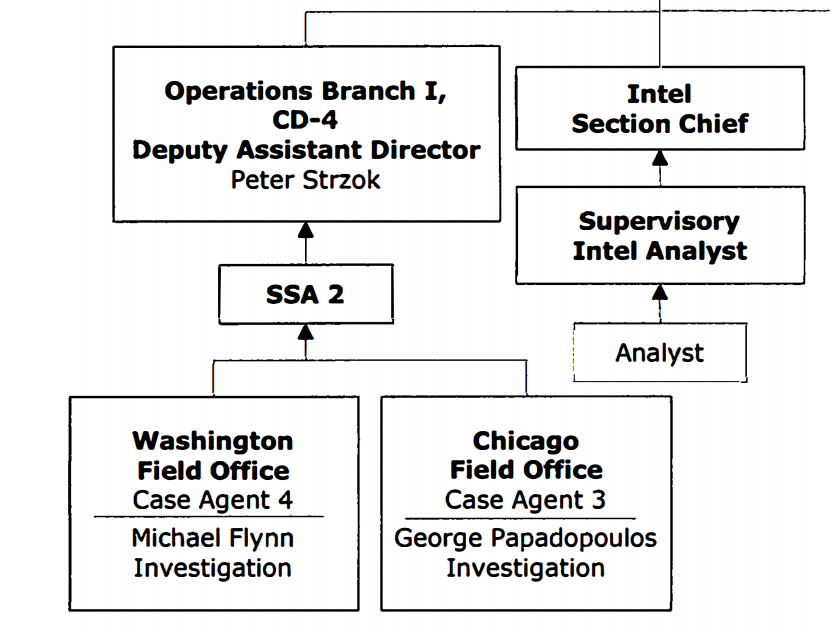

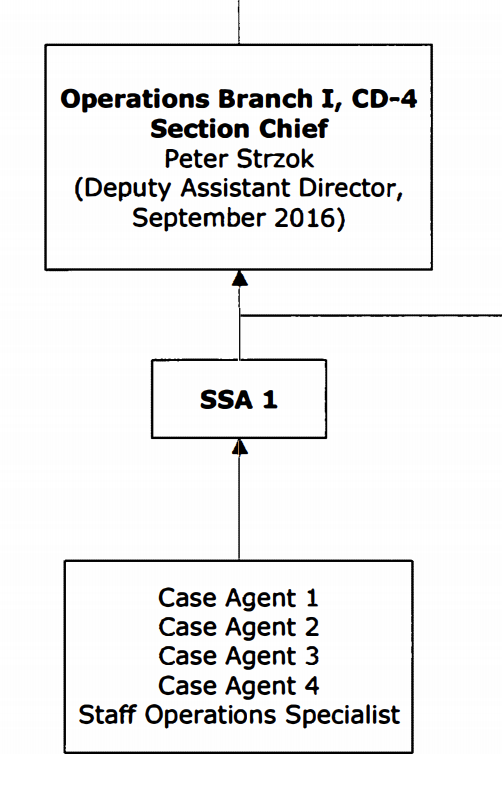

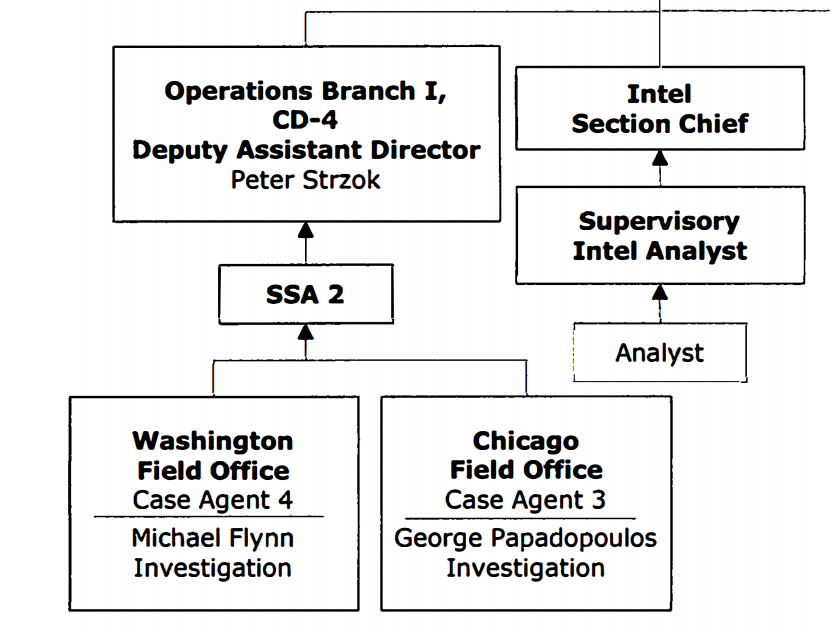

According to the org charts included in the Carter Page IG Report (PDF 116), it appears that Barnett would have been on a combined Crossfire Hurricane team from July 31 to December 2016; the report says he was working on the Manafort case.

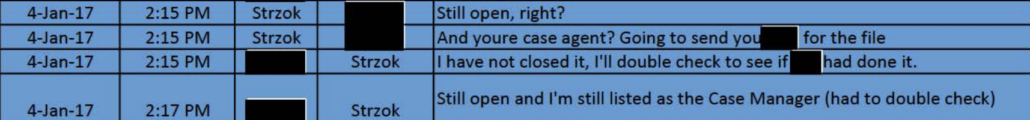

Then, he took over the Flynn case. He would have reported up through someone else who also oversaw the George Papadopoulos investigation, but he would not be part of that investigation.

Even after a subsequent reorganization, that would have remained true until the Mueller investigation, when — by his own description — Barnett remained on the Flynn team.

Early in his 302, Barnett described that he thought the investigation was “supposition on supposition,” which he initially attributed to not knowing details of the case. Much later in the interview, he said he, “believed there were grounds to investigate the other three subjects in Crossfire Hurricane; however, he thought FLYNN was the ‘outlier.'” which conflicts with his earlier claim.

By his own repeated description, Barnett did not open the Flynn case and did not understand why it had been opened (he doesn’t explain that this was an UNSUB investigation, which undermines much of what he says). Moreover, his complaints about the flimsy basis for the Flynn investigation conflict with what Barnett said in the draft closing memo for the investigation, which explained that the investigation was opened,

on an articulable factual basis that CROSSFIRE RAZOR (CR) may wittingly or unwittingly be involved in activity on behalf of the Russian Federation which may constitute a federal crime or threat to the national security.

[snip]

The goal of the investigation was to determine whether the captioned subject, associated with the Trump campaign, was directed and controlled by and/or coordinated activities with the Russian Federation in a manner which is a threat to the national security and/or possibly a violation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act, 18 U.S.C. section 951 et seq, or other related statutes.

A key detail here is that Barnett himself said part of this was an attempt to figure out whether Flynn may have unwittingly been targeted by Russia, which makes his focus on crime in the Jensen interview totally contradictory.

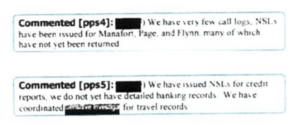

Barnett did explain that NSLs were written up in December but pulled back (these were also released last night, though not with the detail that they were withdrawn). He claimed not to know why the NSLs were withdrawn.

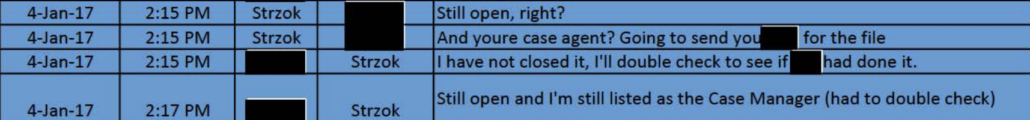

A National Security Letter (NSL) had been prepared to obtain “toll records” for a phone belonging to FLYNN. The request was “pulled back” prior to the records being obtained. Peter Strzok (STRZOK) was the individual who ordered the NSL be pulled back. BARNETT was not told why the NSL was pulled back.

In the draft closing that Barnett himself wrote, he explained that because Flynn was not at that point named as a possible agent of a foreign power, that limited the investigative techniques they might use.

The writer notes that since CROSSFIRE RAZOR was not specifically named as an agent of a foreign power by the original CROSSFIRE HURRICANE predicated reporting, the absence of any derogatory information or lead information from these logical source reduced the number of investigative avenues and techniques to pursue.

That’s also another reason (not noted by Barnett in this interview) why he didn’t get a 215 order.

BARNETT chose not to obtain records through FISA Business Records because he advised this process is comparatively onerous.

Note that Strzok’s order to withdraw the NSL is yet more proof that Strzok was not out to get Flynn.

Barnett also confirmed something else that Strzok has long said — that they chose not to use any overt methods during the election (unlike the Hillary investigation).

BARNETT was told to keep low-key, looking at publicly available information.

Again, this adds to the evidence that no one was out to get Trump.

Barnett also explains how Stefan Halper shared information about Flynn, and he — a pro-Trump agent skeptical of the investigation — decided to chase down the Svetlana Lokhova allegation.

The source reported that during an event [redacted] 2014 FLYNN unexpectedly left the event [redacted] The source alleged FLYNN was not accompanied by anyone other [redacted] BARNETT believed the information concerning [redacted] potentially significant and something that could be investigated. However, Intelligence Analysts did not locate information to corroborate this reporting concerning redacted] FLYNN, including inquiries with other foreign intelligence agencies. BARNETT found the idea FLYNN could leave an event, either by himself or [redacted] without the matter being noted was not plausible. With nothing to corroborate the story, BARNETT thought he information was not accurate.

Later on, Barnett seems to make an effort to spin his inclusion of the Lokhova information in the closing memo as an attempt to help Flynn, describing,

BARNETT wanted to include information obtained during the investigation, including non-derogatory information. BARNETT wanted to include [redacted] specifically [redacted] FLYNN. The [redacted] and FLYNN were only in the same country, [redacted], the same time on one occasion and at that time they were visiting different cities.

That is, something in the closing memo that has been spun as an attack on Flynn he here spins as an attempt to include non-derogatory information, to help Flynn.

I find it curious that the main reason Barnett dismissed this allegation is because he found it implausible that a 30-year intelligence officer would know how to leave a meeting unnoticed. But let it be noted that for over a year, Sidney Powell has suggested that chasing down this tip was malicious targeting of Flynn, and it turns out a pro-Trump agent is the one who chased it down.

In many places, Barnett’s narrative is a muddle. For example, early in his interview, he said that he worked closely with Analyst 1 and Analyst 2. Analyst 2 worked on the Manafort investigation. Barnett had to get the Flynn files from Analyst 1, suggesting Analyst 1 had a key role in that investigation. But then later in the interview, after explaining that Analyst 1, “believed the investigation was an exercise in futility,” Barnett then said that Analyst 3 “was the lead analyst on RAZOR.” Barnett described that Analyst 3 was “‘a believer’ due to his conviction FLYNN was involved in illegal activity,” but also described that Analyst 3 was the one who didn’t want to interview Flynn. But then Barnett explains several other people who did not want to interview Flynn, in part because the pretense Barnett wanted to use (that it was part of a security clearance) was transparently false.

Barnett then explains that he did not change his opinion about whether Flynn was compromised based on reading the transcript (it’s unclear whether he read just one or all of them) of Flynn’s call with Kislyak. He explained that he “did not see a potential LOGAN ACT violation as a major issue concerning the RAZOR investigation.”

There are several points about this request. First, Jeffrey Jensen is taking a line agent’s opinion about a crime as pertinent here, after Billy Barr went on a rant the other day about how line agents and prosecutors don’t decide these things (showing the hypocrisy of this entire exercise). Barnett’s account undermines the disinformation spread before that the Logan Act claim came from Joe Biden, disinformation which Jensen himself wrongly fed. Significantly, Barnett does not appear to have been asked whether he thought the transcripts meant he had to investigate further.

Barnett says “in hindsight” he believes he was cut out of the interview of Flynn, based solely on the norm that normally “a line agent/case agent would do the interview with a senior FBI official present in cases concerning high ranking political officials.” He doesn’t consider the possibility that Joe Pientka did it because he had been in the counterintelligence briefing with Flynn the previous summer, which is what the DOJ IG Report said.

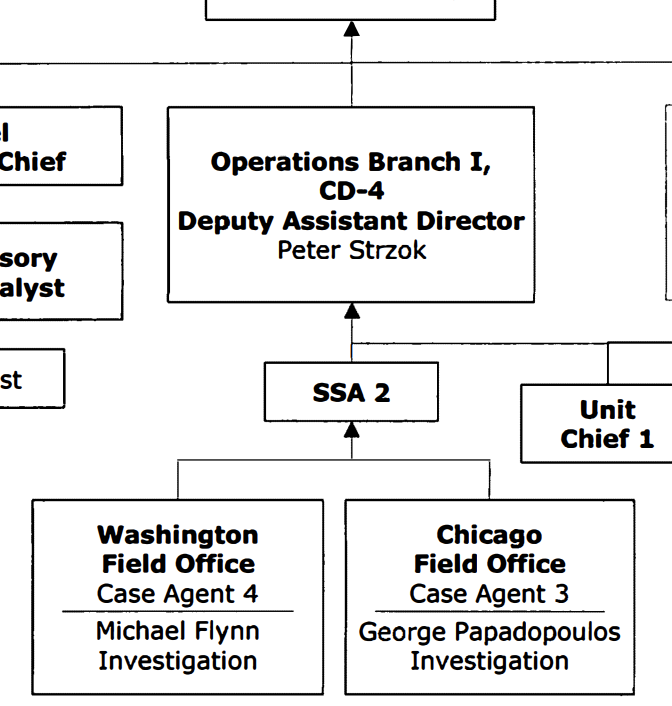

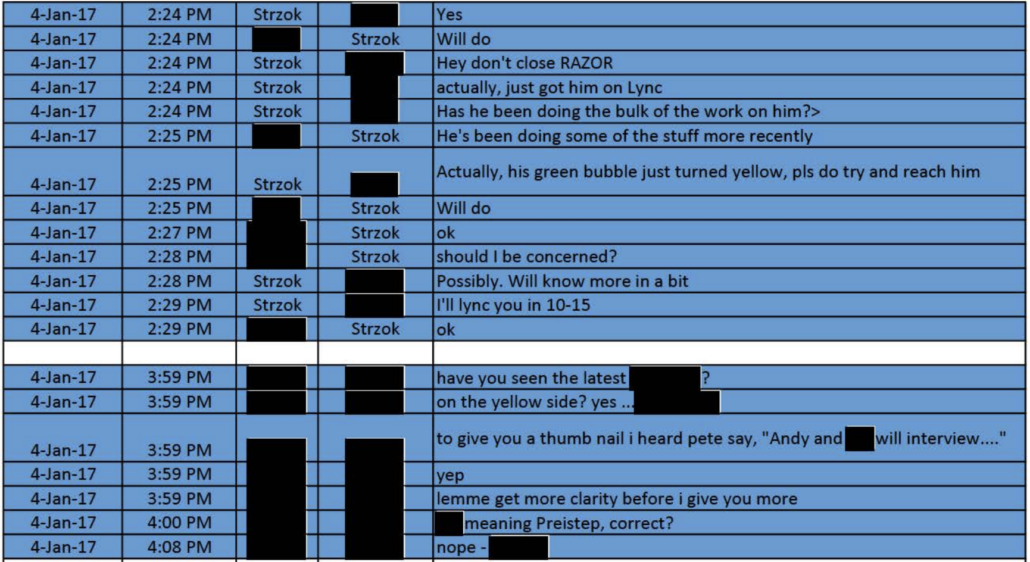

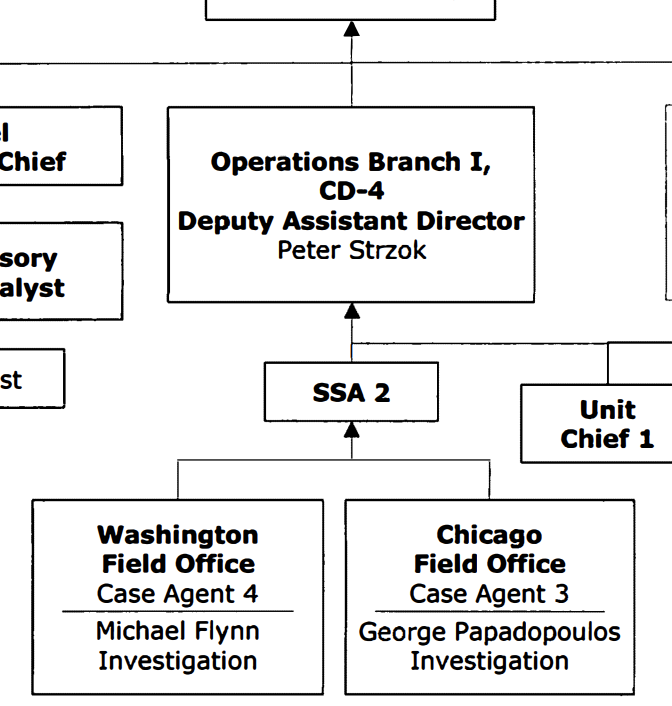

He then says “There was another reorganization of the Crossfire Hurricane investigation after the 1/24/17 interview of Flynn. This conflicts, somewhat, with both the org charts Michael Horowitz did, but also texts already released showing the reorg started in the first days of January (though the texts are consistent with the initial plan for Barnett and Andy McCabe to interview Flynn and I don’t necessarily trust the DOJ IG Report over Barnett), but that was before a lot else happened.

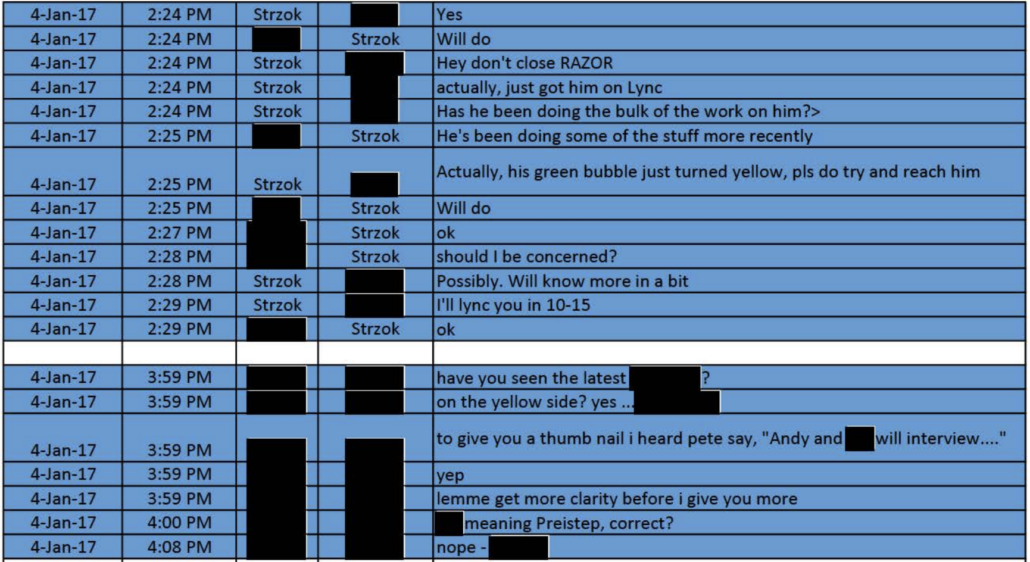

Only after describing a post-interview reorganization does Barnett raise something that all the public record says happened earlier, that, “The FBI was reacting to articles being reported in the news, most notably an article written by Ignatius concerning [redacted] involving FLYNN to a Russian Ambassador.” But even here, Barnett does not talk (nor does he appear to have been asked) about Flynn lying to the press about the intercepts. In other words, Jensen’s investigators simply didn’t address what every single witness says was the most important factor at play in the decision to interview Flynn, his public lies about the calls with Kislyak.

In one place, Barnett claims that “base-line NSLs” were filed “after the article by Ignatius,” which would put it in mid-January, before the interview. Later, he says that “In February 2017, NSLs were being drafted with [SA3] instructing BARNETT what needed to be done,” putting it after Flynn obviously lied in his interview. At best, that suggests Barnett is eliding the timeline in ways that (again) don’t deal with the risk of Flynn’s public lies about the Kislyak call.

Barnett then claims that McCabe was running this (in spite of the involvement of SA3 and his earlier report — and Horowitz’s org chart, not to mention other evidence documents already released — showing the continued involvement of Strzok). Barnett also backed getting NSLs in early 2017, and even insisted, again, that they should have been obtained earlier. Jensen appears to be making a big deal out of the fact that Kevin Clinesmith approved the NSLs against Flynn in 2017.

BARNETT said he sent an e-mail to CLINESMITH on 02/01/2017 asking CLINESMITH about whether the predication information was acceptable, as it was the same information provided on the original NSL request in 2016. CLINESMITH told BARNETT the information was acceptable and could be used for additional NSLs.

There’s a lot that’s suspect about this line of questioning, not least that the predicate for the investigation as a whole was different than the one for Flynn. But I’m sure we’ll hear more about it.

A Strzok annotation of a NYT article that Lindsey Graham released makes it clear that by February 14, 2017, the FBI still hadn’t obtained the returns from most of the NSLs.

Barnett seems to suggest that as new information came in “in BARNETT’s opinion, no evidence of criminal activity and no information that would start a new investigative direction.” If he’s referring to call records (which is what the NSLs would have obtained) that is, frankly, shocking, as the call records would have shown that Flynn also lied about being in touch with Mar-a-Lago before calling Kislyak. It’s what Flynn was trying to hide with his lies! And yet Barnett says that was not suspect.

Then Barnett moved onto the Mueller team. He starts his discussion with another self-contradictory paragraph.

BARNETT was told to give a brief on FLYNN to a group including SCO attorney Jean Rhee (RHEE), [four other people], and possibly [a fifth] BARNETT said he briefly went over the RAZOR investigation, including the assessment that there was no evidence of a crime, and then started to discuss [redacted — probably Manafort] which BARNETT thought was the more significant investigation. RHEE stopped BARNETT’s briefing [redacted] and asked questions concerning the RAZOR investigation. RHEE wanted to “drill down” on the fees FLYNN was paid for a speech FLYNN gave in Russia. BARNETT explained logical reasons for the amount of the fee, but RHEE seemed to dismiss BARNETT’s assessment. BARNETT thought RHEE was obsessed with FLYNN and Russia and she had an agenda. RHEE told BARNETT she was looking forward to working together. BARNETT told RHEE they would not be working together.

First, by his own description, Barnett was asked to brief on Flynn, not on Manafort (or anyone else); he was still working Flynn and not (if Horowitz’s org chart is to be trusted) involved anymore with Manafort at all. So if he deviated from that, he wasn’t doing what he was supposed to do in the briefing, which might explain why people in the briefing asked him to return to the matter at hand, Flynn. Furthermore, in much of what comes later, Barnett claims the prosecutors overrode the agents (in spite of the fact that, as shown, the final conclusion of the report sided with Barnett). But Barnett here shows that from his very first meeting with Mueller prosecutors, he was the one being bossy, not the prosecutors.

Update: I’ve since learned that the redacted information pertains to the Flynn Turkey case. The point about Rhee still stands, however. Rhee was in charge of the Russian side of the investigation. She asked questions about the Russian side of the investigation. She was polite and professional. He responded by being an abusive dick. What this paragraph shows is that Barnett has a workplace behavior problem, and he used his own workplace behavior problem to try to attack the female colleague he was being an asshole to.

Barnett’s continued complaints about Rhee (and Weissmann) are nutty given that, as a Flynn agent, he wouldn’t have been working with them.

Barnett claims that,

In March or April 2017, Crossfire Hurricane went through another reorganization. All of the investigations were put together.

The timing coincides with, but the structure does not match, what appears in the Carter Page IG Report (though, again, I don’t necessarily assume DOJ IG got it right).

Then Barnett makes a claim that conflicts with a great deal of public facts:

On 05/09/2017, COMEY was fired which seemed to trigger a significant amount of activity regarding Crossfire Hurricane. Carter Page was interviewed three times and PAPADOPOULOS was also interviewed. Both investigations seemed to be nearing an end with nothing left to pursue. the MANAFORT case was moved from an investigative squad to a counter intelligence squad [redacted] The Crossfire Hurricane investigations seemed to be winding down.

The appointment of the SCO changed “everything.”

At least according to the Horowitz org chart, these weren’t his investigations. A list of interviews shows that FBI had not interviewed the witnesses to Carter Page’s trip before June 2017 (though it is true that the investigation into him was winding down). The details of the Papadopoulos investigation would have shown that it was after at least the first (and given the Strzok note about NSLs) after probably several more interviews before the FBI discovered that Papadopoulos tried to hide extensive contacts with Russians by deactivating his Facebook account. Mueller didn’t even obtain Papadopoulos’ Linked In account until July 7, 2017, and that was just the second warrant obtained by Mueller’s prosecutors, almost three months after he was appointed; that warrant would have disclosed Papadopoulos’ ties to Sergei Millian and further contacts with the Russians. Some of the earliest activity in the investigation pertain to Michael Cohen (in an investigation predicated off of SARs), with the Roger Stone investigation barely beginning in August, neither of which are included in Barnett’s comments. And Barnett makes no mention of the June 9 meeting, discovered only as a result of Congress’ investigations, which drove some of the early investigative steps.

Which is to say, the evidence seems to have changed everything. And yet he says it was Mueller.

And yes, Jim Comey’s firing is part of that. But as to that, Barnett has this ridiculous thing to say:

As another example [of a “get Trump” attitude] BARNETT said the firing of FBI Director COMEY was interpreted as obstruction when it could just as easily have been done because TRUMP did not like COMEY and wanted him replaced.

Well, sure, in the absence of the evidence that might be true. But not when you had Comey’s memos that described how, first of all, Trump had committed to keeping Comey on (meaning he didn’t not like Comey!) but afterwards had tried to intervene in an ongoing investigation. It’s possible Barnett did not know that in real time — it wasn’t his investigation — but it’s not a credible opinion given what is in the memos.

Barnett also claims, as part of his “proof” that people wanted to get Trump that,

Concerning FLYNN, some individuals in the SCO assumed FLYNN was lying to cover up collusion between the TRUMP campaign and Russia. BARNETT believed Flynn lied in the interview to save his job, as that was the most plausible explanation and there was no evidence to contradict it.

Yes. There is evidence. The evidence is that Flynn’s lies hid his consultations with Mar-a-Lago, about which he also lied.

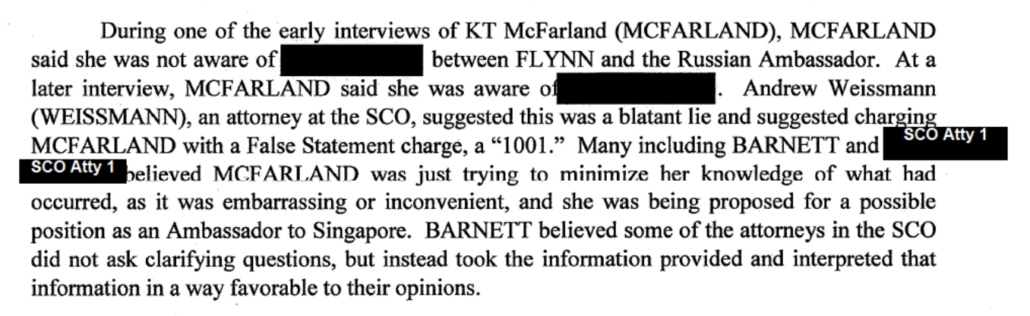

In a passage similarly suggesting that KT McFarland told the same lies that Flynn did because she wanted to get the Singapore job, Barnett seems to refer to (and DOJ seems to have redacted) a reference to Brandon Van Grack (who is the only Mueller prosecutor whose name would span two lines).

If that is, indeed, a reference to Van Grack, then it means DOJ is hiding evidence that Van Grack (along with Strzok) was not biased against Flynn.

Note, too, that Barnett doesn’t reveal that McFarland only unforgot her conversations with Flynn after Flynn pled guilty, which has a significant bearing on how credible that un-forgetting was. Nor does he note that Mueller didn’t charge McFarland with lying. The Mueller Report almost certainly has a declination description for why they didn’t charge McFarland, which (if true), would make a second thing where Barnett’s minority opinion had been determinative for the actual report, in spite of his claim that the prosecutors were running everything.

Finally, the 302 notes that Barnett was asked about whether he “wiped” his own phone.

BARNETT had a cellular telephone issued by the SCO which he did not “wipe.” BARNETT did hear other agents “comically” talk about wiping cellular telephones, but was not aware of anyone “wiping” their issued cellular telephones. BARNETT said one agent had a telephone previously issued to STRZOK.

If this were even a half serious investigation, Barnett would have been asked to back that claim with names. He was not.

What Billy Barr and Jeffrey Jensen have done is show that the only witness they’ve found to corroborate their claims can’t keep his story straight from one paragraph to another, and claims to be ignorant of several central pieces of evidence against Flynn.

That’s all they have.

Given that this post takes such a harsh view on Barnett, reminder I went to the FBI in 2017 regarding someone with no ties to Trump but who sent me a text about (and denigrating) Flynn.