DOJ Still Claiming Its Kid Glove Oversight of Prosecutors Is Adequate

During the uproar over Jim Comey’s role in the Hillary email investigation, a lot of commentators figured it’d all come out in an Inspector General report. But as I noted, DOJ exempts its lawyers from normal kind of oversight, subjecting them instead to Office of Professional Responsibility investigations without statutory independence. The problem has been debated at least since 2007, but Congress squelched efforts to change it in 2008. That, helped by the interference of the now-deceased David Margolis, was how John Yoo got off after writing shoddy memos authorizing torture.

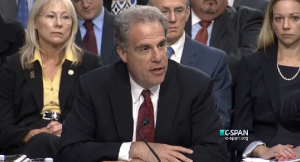

Last month, DOJ’s IG released its yearly review of top management challenges. And, as Michael Horowitz’s predecessor Glenn Fine had done before him, he made a bid for being able to review the conduct of DOJ’s lawyers. The report argues that the oversight for lawyers should be the same as it is for agents.

The OIG, however, does not have authority to investigate allegations of misconduct against Department attorneys when the allegations are related to their work as lawyers. Those allegations fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility. The OIG has long believed that there is no principled basis for this continued limitation on our jurisdiction, and no reason to treat the investigation of misconduct by prosecutors differently than misconduct by agents. Under the current system, misconduct allegations against agents are handled by a statutorily independent OIG, while misconduct allegations against prosecutors are handled by a Department component that lacks statutory independence and whose leadership is both appointed by and removable by the Department’s leadership.

As Horowitz has done with IG statutory independence with respect to accessing evidence, the report focuses on bills to address the problem.

Bipartisan bills pending in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate would remove this limitation on the OIG’s jurisdiction. The legislation, as now proposed, would allow the OIG to investigate these important matters, where appropriate, with the independence and transparency that is the touchstone of all of the OIG’s work, thereby providing the public with confidence regarding the handling of these matters. The Department’s attorneys should be held to the same standards of oversight as other Department components, and the OIG should have oversight over all Department employees, just like every other OIG.

Most interesting, however, is the way that DOJ claimed this long-established problem doesn’t exist. Unbelievably, “the Department” claimed that OPR has the same independence as OIG.

In response to a draft of this report, the Department questioned our position that the OIG should have the same authority as every other federal Inspector General to review allegations of misconduct by Department attorneys in connection with their work as lawyers. Among other things, the Department took issue with our description of OPR’s relative lack of independence as compared to the OIG by asserting that (1) OPR’s Counsel “remains unchanged with successive Attorneys General and presidential administrations,” (2) the OIG has not “criticized OPR’s work, the thoroughness of its investigations, or the soundness of its findings,” and (3) the OIG has not “identified a single OPR investigation that failed to appropriately hold accountable . . . Department attorneys.”

The report calls bullshit on the claim that the department hasn’t replaced OPR officials, noting that Holder did replace OPR Counsel Marshall Jarret in 2009 in the midst of the Ted Stevens scandal (Jarret was also backing off promises he would make the results of the Yoo investigation with Congress).

On the first point, the same could be said of supervisory attorneys throughout the Department and, in fact, contrary to the Department’s claim with regard to OPR, in April 2009, less than 4 months after the last change in presidential administrations, the new Attorney General replaced the OPR Counsel without any public explanation.

Holder actually replaced the OPR Counsel one more time, in 2011.

The report goes on to note that we can’t assess OPR’s work because, unlike most IG Reports, it is not public.

On the second and third points, neither the OIG nor the public are in a position to fully assess the thoroughness and soundness of OPR’s work precisely because OPR does not disclose sufficient information to allow for such an assessment.

The report then lists off a bunch of people — including the judge in the Ted Stevens case, Emmet Sullivan — who have complained about OPR’s work.

However, federal judges, the American Bar Association, and the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) have all questioned the level of independence, transparency, and accountability of OPR. See, e.g., Order by Hon. Emmet G. Sullivan Appointing Henry F. Schuelke Special Counsel in United States v. Stevens, No. 08-cr-231 (Apr. 7, 2009), p. 46. (“the events and allegations in this case are too serious and too numerous to be left to an internal investigation that has no outside accountability”) ; “Criminal Law 2.0,” by Hon. Alex Kozinski, 44 Geo. L.J. Ann. Rev. Crim. Proc. iii (2015); ABA Recommendation urging the Department of Justice to release “as much information regarding individual investigations as possible,” Aug. 9-10, 2010, available here; “Hundreds of Justice Department Attorneys Violated Professional Rules, Laws, or Ethical Standards: Administration Won’t Name Offending Prosecutors,” Report by POGO, March 13, 2014, available here.

The report ends with a reassertion that the Inspector General Act requires far more of inspectors general than OPR provides.

Moreover, whatever the soundness of OPR’s work, the Department’s efforts to equate OPR’s independence and transparency with that of the OIG flies directly in the face of the Inspector General Act, which fundamentally exists to create entities with an enhanced degree of independence and transparency so that they can credibly conduct investigations and reviews where there would be an expectation that more independent and transparent oversight is required. That is the very reason why Attorney General Ashcroft expanded the OIG’s jurisdiction in 2001 to include the FBI and the DEA, and there simply is no reason why Department attorneys continue to be protected from the possibility that their conduct may warrant independent review by the OIG in appropriate cases.

Frankly, there is evidence that OPR’s investigation has been inadequate, starting with both the Yoo and the Stevens investigations.

But there have also been a slew of cases of prosecutors withholding evidence from defendants, cases that ought to merit some real review (to say nothing of the Clinton email case). For example, just this week, Ross Ulbricht’s lawyers revealed they had discovered evidence of a third corrupt agent, the evidence of which had been withheld from the defense team.

There’s no hint of why Horowitz is making this point now. But there sure are a number of cases that might elicit actual independent review.