Tulsi Gabbard Teams Up with Russian Spies to Wiretap and Unmask Hillary Clinton

I joked the other day that it’s as if Trump offered his cabinet members a free condo for whomever best distracted from his Epstein problem.

Tulsi Gabbard is, thus far, winning the contest for the sheer shamelessness of her ridiculous claims.

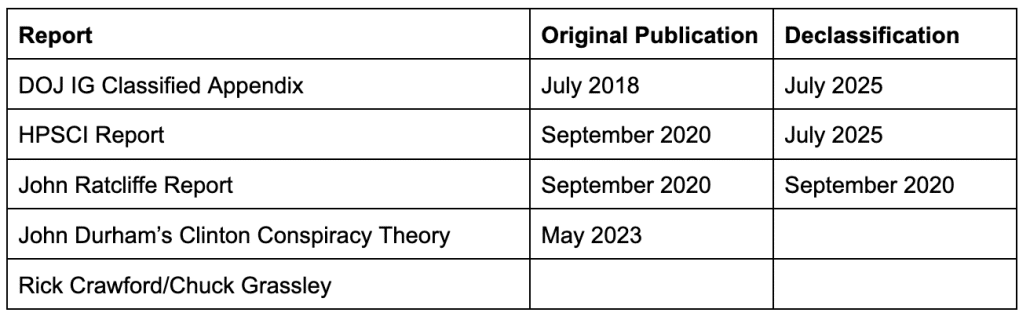

She has manufactured claims of sedition out of her conflation — whether deliberate or insanely ignorant — of voting machines and the DNC server, built on top of President Obama’s perfectly reasonable request to document all the ways Russia tampered in the 2016 election. Then, she released a different report — a 2020 GOP HPSCI report complaining about Intelligence Community tradecraft in the 2017 Intelligence Community Assessment. The HPSCI Report not only exhibits all the tradecraft failure it complains about, but it conflicts in some ways with her original propaganda.

In a presser at the White House yesterday (skip ahead to 12:30), Tulsi went one better, presenting the contents of the HPSCI report without context, focusing closely on a section that cites a cherrypicked selection of Russian intelligence reports purportedly (but not certainly) based off documents stolen from Democrats, the State Department, and a think tank.

Tulsi stood at the podium of the White House press room and delivered Russian intelligence, with an occasional “allegedly” thrown in, without explaining clearly that’s what she was doing.

In so doing, the Director of National Intelligence effectively teamed up with Russian spies, parroting analysis those Russian spies did on documents stolen from Hillary and people associated with her, without masking Hillary’s identity as required by intelligence protocol. This is precisely the kind of (then unsubstantiated) abuse that first animated right wing grievance back in 2017, outrage over the possible politicized unmasking of political adversaries, carried out by the head of intelligence from the White House podium.

They have become the monsters they warned about.

The SVR documents

Let me explain the documents. By 2016, there were actually two parallel Russian hacking campaigns targeting Hillary (and others). One, starting in 2016 and conducted by Russia’s military intelligence (GRU, often referred to as APT 28), obtained and caused the dissemination of documents during the election — the hack-and-leak campaign that Trump exploited to win the election. But starting years before that, Russia’s foreign intelligence service (SVR, often referred to as APT 29) targeted a number of traditional spying targets, including the White House, DOD, and State, some think tanks viewed as adversarial to Russia, and the DNC.

Here’s a report on APT 29’s hacking campaigns published in September 2015, which I wrote about here. Here’s a more recent history that includes those earlier hacks. I’ve been told that the interactions between APT 29 and APT 28 hackers inside Democratic servers was visible, but reluctant. APT 29 had and still has the more skillful hackers.

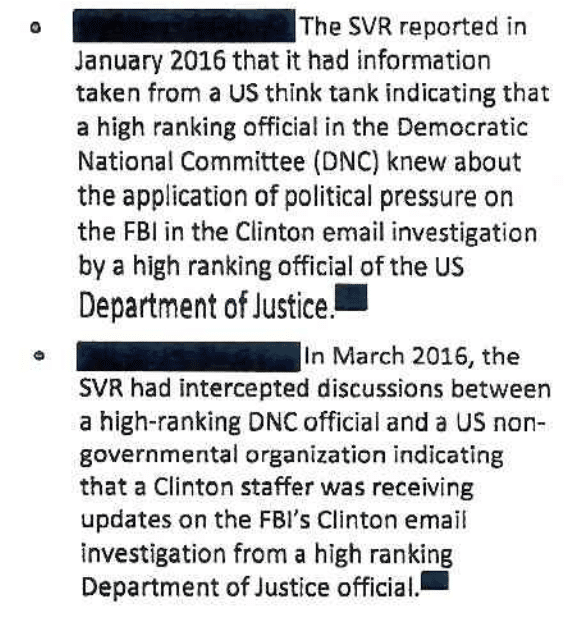

Unlike GRU, SVR did not use most of the files it stole in a hack-and-leak campaign. Russian spies analyzed the documents and wrote reports on them, like normal spying. But then someone — some other spying service, probably — spied on their spying efforts. And that entity shared what they found, including both the things SVR stole and the reports that Russian spies wrote about those stolen files, with the US Intelligence Community. And starting at least by 2018, right wingers have been obsessed with those stolen files and Russian intelligence reports, using them to feed one after another investigation into Democrats.

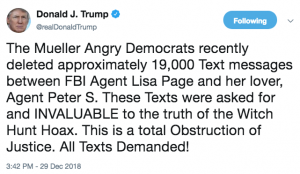

This gets a bit confusing, because we’re seeing the results of that obsession out of order. We first saw a right wing campaign based off them when John Ratcliffe, then the Director of National Intelligence, released a report about one particular analytical report, then released background documents; both were used as part of the effort to undermine the Mike Flynn prosecution in advance of the 2020 election. That particular report — allegedly claiming that in July 2016, Hillary endorsed a plan to focus on Trump’s ties to Russia to distract from the Clinton email investigation — served as the animating force for the Durham investigation, though Durham had to fabricate new details in the intelligence to do so. For years, Chuck Grassley has been frothing to release a classified appendix of the 2018 DOJ IG Report on the Clinton email investigation that pertained to the SVR documents, which Pam Bondi released the other day. Yesterday’s propaganda presser was based on the release of a 2020 critique of the 2017 Intelligence Community Assessment of the 2016 hack (there were earlier versions in which Kash Patel was involved), written by Republicans on the House Intelligence Committee (HPSCI).

We’re surely not done. There’s a classified annex to the Durham report in which he tries to justify treating Russian intelligence product as true. And yesterday, Grassley and House Intelligence Chair Rick Crawford asked to get more of the SVR files, this time focused on Barack Obama.

So, these documents were addressed at length by Michael Horowitz (it’s not yet clear how prominently they figure in earlier HPSCI work), then packaged up as part of Trump’s reelection bid in 2020, then further fluffed up by Durham in his failed prosecution effort and, on top of these recent releases, will no doubt feed the frothers indefinitely. But this order matters, because right wingers kept forgetting what they learned in earlier iterations of this obsession.

The 2018 classified annex

The DOJ IG classified annex considers FBI’s treatment of two kinds of files from that SVR collection: first, report(s) claiming that Loretta Lynch was trying to cover up the Clinton investigation and Jim Comey was trying to exacerbate it (Comey only appears in one), and, also, a set of files that might have raw State Department documents stolen by Russia that could be used to investigate Hillary.

The reports became important to Horowitz’ discussion of the Clinton email investigation because Jim Comey claimed in June 8, 2017 congressional testimony that one reason why he decided to make the prosecutorial decision on the Clinton investigation is because he worried that the two reports on Lynch might leak.

The raw intelligence became a focus because early on, alleged Trump adversary Peter Strzok sought to review the raw collection, a request that ultimately fell through the cracks, which Grassley uses to claim the investigation was not diligent enough.

A several page section of the report describing the collection — eight thumb drives, along with a set of data provided via other means — makes clear that, on top of normal concerns about allowing the FBI to review stolen US person data, the hesitation to access the data arose from the large number of privileged files, from the White House, from State, and from Congress, in there.

- Thumb drives 1-5: These thumb drives included files stolen from US victims, including the Executive Office of the President, the State Department, and the House of Representatives, probably including a number of unknown US victims. The FBI did analyze these files, which helped them to identify where the Obama ones came from, that the Russians had obtained “advance intelligence about a planned FBI arrest of a Russian citizen,” and network maps of classified US government systems. Two drives, drives 3 and 4, “focused primarily on State Department communications,” as did much of the content of the other thumb drives. The FBI never comprehensively reviewed these files because of concerns about Executive and Congressional privileges tied to the victims. The FBI has queried them, three times:

- In early 2016, FBI queried the drives using some approved keywords, apparently to understand Russia’s targets.

- FBI later conducted a second set of limited queries, without reading the actual content. It did, however, create a “word cloud” of what was in the US victim data, which FBI treated as an index.

- In August 2017, FBI OGC permitted an analyst working with Mueller to query the word cloud index on Clinton and clintonemail.com.

- Thumb drives 6 and 7: These drives appear to include Russia’s reports about their hacks; victim data was included as attachments. The FBI permitted analysts to review non-victim data for foreign intelligence and evidentiary purposes, but not any content from the Executive Office of the President, State, or Congress.

- Thumb drive 8: This data was never uploaded until 2018 and by the time of this report (also 2018) had never been reviewed. It was believed to include data redundant to what was on drives 1-5, including privileged material.

- Post-8 data: This data appears to have come to the FBI via a medium other than a thumb drive. Their source filtered out certain kinds of victim data before passing it on. It also was unlikely to have the privileged sources of information — from EoP, State, and the House of Representatives — that presented concerns about the data on thumb drives 1-5. The FBI was permitted to review this data under the same rules as applied to Thumb drives 6 and 7 — that is, they could review the non-victim information.

Staring in August 2016, Andy McCabe started asking to access all eight drives. While the Obama White House told the FBI in October 2016 that their request for access was overly broad, they never got around to negotiating that access because the FBI was too busy working on the Russian investigation and exploiting Anthony Weiner’s laptop. White House Counsel Neil Eggleston circled back on this issue in his last day on the job, January 19, 2017.

Ironically, the most aggressive attempt to access these files up to the IG Report came from an analyst on the Mueller team — no doubt someone who has subsequently been fired. The IG Report describes that this person likely exceeded search protocols prohibiting searches on victim information, including on Clinton and clintonemail. Now, however, Trump will undoubtedly use Tulsi’s propaganda campaign as an excuse to read emails stolen from Barack Obama, waiving any privilege concerns (indeed, that should be understood as one goal of the task force Bondi set up yesterday, to collude with Russian spies to spy on President Obama).

For the purposes of understanding how Tulsi colluded with Russian spies yesterday, the most important detail from the classified annex is that the FBI didn’t treat the two Loretta Lynch reports as credible — the report describes that FBI considered them “objectively false.”

[W]itnesses told us that the reports were not credible on their face for various reasons, including that they contained information that the FBI knew to be “objectively false.”

One reason they likely believed that is because one of the two Lynch reports said that Comey was deliberately trying to stall the investigation.

Comey is leaning more to the [R]epublicans, and most likely he will be dragging this investigation until the presidential elections; in order to effectively undermine the chances for the [Democratic Party] to win the presidential elections. [brackets original]

It also revealed that the FBI never found the underlying stolen documents on which the reports were purportedly based — at one point, the DOJ IG Report notes that it wasn’t clear “if such communications in fact existed.”

The FBI didn’t believe these documents were credible.

But if you do believe the reports are credible — if you treat the reports as “true” — then it is not just “true” that Jim Comey was stalling the Clinton email investigation to help Republicans, but Russia believed that Comey was stalling the Clinton email investigation to help Republicans win the election.

HPSCI’s Jim Comey problem

The HPSCI report includes these SVR files, years after the FBI determined at least two of them were not credible, as “true” statements of Putin’s belief. I’ll write up the entire report separately; parts of it are quite rigorous and interesting, while the section on the Steele dossier was riddled with errors and this part — the part that relies on these SVR reports — was sort of an exercise in desperation to find as many reasons to discredit the claim that Putin tried to help Trump get elected as possible. This section is the mirror image of what the report alleges John Brennan was engaged in with the 2017 ICA Report, intelligence analysis that came to a conclusion and then found intelligence to back that conclusion. They include the SVR reports to argue that if Putin really wanted Trump to win, he would have released all these reports.

In a page and a half, the HPSCI report cites one after another of these reports.

- In September 2016, Russian spies claimed that President Obama found Hillary’s health to be “extraordinary alarming.”

- Russian spies claimed it had communications showing Hillary was suffering from “psycho-social problems” and even (Tulsi parroted there in the White House) “was placed on a regimen of ‘heavy tranquilizers’.”

- Russian spies claimed Hillary had Type 2 Diabetes and deep vein thrombosis.

- The claim — which John Ratcliffe noted could “reflect exaggeration or fabrication” in his report in 2020 — that Hillary had a plan to link Trump and Putin to distract from the Clinton email investigation.

- Russian spies claimed Hillary traded financial funding for electoral support with religious organizations in post-Soviet countries.

- US allies in London, Berlin, Paris, and Rome doubted her ability to perform the functions of President.

- European government experts assessed that Trump’s only chance of winning was allegations about the Clinton Foundation.

The HPSCI Report includes in three bullets the allegations laid out in the two reports described in the IG Report, split up across two pages, as if they represent three reports.

Not only do they ignore that the FBI viewed at least some of these reports as “not credible,” nor address the question of whether these reflected real intercepts at all.

But they don’t mention that the first of those two reports (probably the January 2016 one) also claimed that Jim Comey was going to stall the investigation to help Trump win.

If you believe the reports were “true,” then you believe that Jim Comey had a plan to help Trump win — much like what he did do — and that Putin shared that same belief.

It was bad enough that a bunch of right wing Congressmen desperate to create a propaganda document to help Trump get elected in 2020 exhibited such shoddy tradecraft.

But yesterday, the Director of National Intelligence stood at a White House podium and repeated one after another Russian intelligence report about which multiple entities have raised serious questions as to its accuracy.

In the guise of complaining about politicized spies exercising inadequate due diligence, Tulsi Gabbard just parroted these Russian intelligence reports — reports that either rely on intercepts of an American citizen or just make shit up — uncritically.

This was Russian spy product, delivered from the White House, from the head of US intelligence.

Links

A Dossier Steal: HPSCI Expertly Discloses Their Own Shoddy Cover-Up

Think of the HPSCI Report as a Time Machine to Launder Donald Trump’s Russia Russia Russia Claims

Tulsi Gabbard and John Ratcliffe Reveal Putin “Was Counting on” a Trump Win

Tulsi Gabbard Teams Up with Russian Spies to Wiretap and Unmask Hillary Clinton

The Secrets about Russia’s Influence Operation that Tulsi Gabbard Is Still Keeping from Us

Tulsi Gabbard Accuses Kash Patel of Covering Up for the Obama Deep State