Update, 1/6/14: I just reviewed this post and realize it’s based on the misunderstanding that the February 24 OLC opinion is from last year, not 2006. That said, the analysis of the underlying tensions that probably led to the use of Section 215 for the phone dragnet are, I think, still valid.

According to ACLU lawyer Alex Abdo, the government may provide more documents in response to their FOIA asking for documents relating to Section 215 on November 18. Among those documents is a February 24, 2006 FISA Court opinion, which the government says it is processing for release.

That release — assuming the government releases the opinion in any legible form — should solve a riddle that has been puzzling me for several weeks: whether the FISA Court wrote any opinion authorizing the phone dragnet collection before its May 24, 2006 order at all.

The release may also provide some insight on why former Assistant Attorney General David Kris concedes the initial authorization for the program may have been “erroneous.”

More broadly, it is important to consider the context in which the FISA Court initially approved the bulk collection. Unverified media reports (discussed above) state that bulk telephony metadata collection was occurring before May 2006; even if that is not the case, perhaps such collection could have occurred at that time based on voluntary cooperation from the telecommunications providers. If so, the practical question before the FISC in 2006 was not whether the collection should occur, but whether it should occur under judicial standards and supervision, or unilaterally under the authority of the Executive Branch.

[snip]

The briefings and other historical evidence raise the question whether Congress’s repeated reauthorization of the tangible things provision effectively incorporates the FISC’s interpretation of the law, at least as to the authorized scope of collection, such that even if it had been erroneous when first issued, it is now—by definition—correct. [my emphasis]

That “erroneous” language comes not from me, but from David Kris, one of the best lawyers on these issues in the entire country.

And the date of the opinion — February 24, 2006, 6 days before the Senate would vote to reauthorize the PATRIOT Act having received no apparent notice the Administration planned to use it to authorize a dragnet of every American’s phone records — suggests several possible reasons why the original approval is erroneous.

Possibility one: There is no opinion

The first possibility, of course, is that my earlier guess was correct: that the FISC court never considered the new application of bulk collection, and simply authorized the new collection based on the 2004 Colleen Kollar-Kotelly opinion authorizing the Internet dragnet. In this possible scenario, that February 2006 opinion deals with some other use of Section 215 (though I doubt it, because in that case DOJ would withhold it, as they are doing with two other Section 215 opinions dated August 20, 2008 and November 23, 2010).

So one possibility is the FISA Court simply never considered whether the phone dragnet really fit the definition of relevant, and just took the application for the first May 24, 2006 opinion with no questions. This, it seems to me, would be erroneous on the part of FISC.

Possibility two: FISC approved the dragnet based on old PATRIOT knowing new “relevant to” PATRIOT was coming

Another possibility is that the FISA Court rushed through approval of the phone dragnet knowing that the reauthorization that would be imminently approved would slightly different language on the “relevance” standard (though that new language was in most ways more permissive). Thus, the government would already have an approval for the dragnet in hand at the time when they applied to use it in May, and would just address the “relevance” language in their application, which we know they did.

In this case, the opinion would seem to be erroneous because of the way it deliberately sidestepped known and very active actions of Congress pertaining to the law in question.

Possibility three: FISC approved the dragnet based on new PATRIOT language even before it passed

Another possibility is that FISC approved the phone dragnet before the new PATRIOT language became law. That seems nonsensical, but we do know that DOJ’s Office of Intelligence Policy Review briefed FISC on something pertaining to Section 215 in February 2006.

After passage of the Reauthorization Act on March 9, 2006, combination orders became unnecessary for subscriber information and [one line redacted]. Section 128 of the Reauthorization Act amended the FISA statute to authorize subscriber information to be provided in response to a pen register/trap and trace order. Therefore, combination orders for subscriber information were no longer necessary. In addition, OIPR determined that substantive amendments to the statute undermined the legal basis for which OIPR had received authorization [half line redacted] from the FISA Court. Therefore, OIPR decided not to request [several words redacted] pursuant to Section 215 until it re-briefed the issue for the FISA Court. 24

24 OIPR first briefed the issue to the FISA Court in February 2006, prior to the Reauthorization Act. [two lines redacted] [my emphasis]

Still, this passage seems to reflect an understanding, at the time DOJ briefed FISC and at the time that the FISC opinion was written that the law was changing in significant ways (some of which made it easier for the government to get IDs along with the Internet metadata it was collecting using a Pen Register).

This would seem to be erroneous for timing reasons, in that the judge issued an opinion based on a law that had not yet been signed into law, effectively anticipating Congress.

The looming threat of Hepting v. AT&T and Mark Klein’s testimony

Which brings me to why. The 2009 Draft NSA IG Report describes some of what went on in this period.

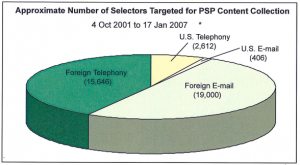

After the New York Times article was published in December 2005, Mr. Potenza stated that one of the PSP providers expressed concern about providing telephone metadata to NSA under Presidential Authority without being compelled. Although OLC’s May 2004 opinion states that NSA collection of telephony metadata as business records under the Authorization was legally supportable, the provider preferred to be compelled to do so by a court order.

As with the PR/TT Order, DOJ and NSA collaboratively designed the application, prepared declarations, and responded to questions from court advisors. Their previous experience in drafting the PRTT Order made this process more efficient.

The FISC signed the first Business Records Order on 24 May 2006. The order essentially gave NSA the same authority to collect bulk telephony metadata from business records that it had under the PSP. And, unlike the PRTT, there was no break in collection at transition.

But the IG Report doesn’t explain why the telecom(s) started getting squeamish after the NYT scoop.

It doesn’t mention, for example, that on January 17, 2006, the ACLU sued the NSA in Detroit. A week after that suit was filed, Attorney General Alberto Gonzales wrote the telecoms a letter giving them cover for their cooperation.

On 24 January 2006, the Attorney General sent letters to COMPANIES A, B, and C, certifying under 18 U.S.C. 2511 (2)( a)(ii)(B) that “no warrant or court order was or is required by law for the assistance, that all statutory requirements have been met, and that the assistance has been and is required.”

Note, this wiretap language pertains largely to the collection of content (that is, the telecoms had far more reason to worry about sharing content). Except that two issues made the collection of metadata particularly sensitive: the data mining of it, and the way it was used to decide who to wiretap.

More troubling still to the telecoms, probably, came when EFF filed a lawsuit, Hepting, on January 31 naming AT&T as defendant, largely based on an LAT story of AT&T giving access to the its stored call records.

But I’m far more interested in the threat that Mark Klein, the AT&T technician who would ultimately reveal the direct taps on AT&T switches at Folsom Street, posed. Read more →