Journalists Struggle to Distinguish Elon Musk’s Chat from Press Conference They Validated

There’s a funny structure to WaPo’s story, bylined by five journalists, on Elon Musk’s chat with Donald Trump.

After discussing the technical problems that delayed the chat for 40 minutes — which Musk attributed to a DDOS attack, a claim anonymous Xitter employees disputed — it described how Musk “allowed the former president to deliver his preferred talking points and a stream of false statements” and mostly kept it comfortable. Then it contrasted that chatty style with the “challenging questions” Rachel Scott and Kadia Goba asked at the NABJ.

Musk billed the conversation with Trump as “unscripted with no limits on subject matter.” But during much of the discussion, he focused on comfortable topics for Trump, such as undocumented immigration. He also allowed the former president to deliver his preferred talking points and a stream of false statements, giving the chat some of the hallmarks of Trump’s signature campaign rallies.

The friendly conversation came after Trump reacted combatively to challenging questions at the National Association of Black Journalists convention — and as the GOP nominee is also attacking Harris for not doing interviews since she announced her campaign for president. Trump reiterated that criticism of Harris on the X Space and repeated his frequent claim that Harris’s rise to the top of the Democratic ticket amounted to a “coup.”

Those were paragraphs three and four.

Twelve paragraphs later, WaPo mentioned — with no comment on any challenge presented by journalists involved — the presser last week, where journalists allowed Trump to make the very same attacks that Musk did.

He has drawn headlines for falsely questioning her heritage, reigniting a feud with Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp (R) and holding a meandering news conference last week.

It’s as if there were no journalists with agency at that presser.

In his first three paragraphs, NYT’s Michael Gold was more succinct. He focused on technical issues, softball questions, and false claims.

What was supposed to be Donald J. Trump’s triumphant return to a social-media platform central to his presidency was marred by glitches on Monday night, when a livestreamed conversation on X between Mr. Trump and its owner, Elon Musk, was significantly delayed by technical issues.

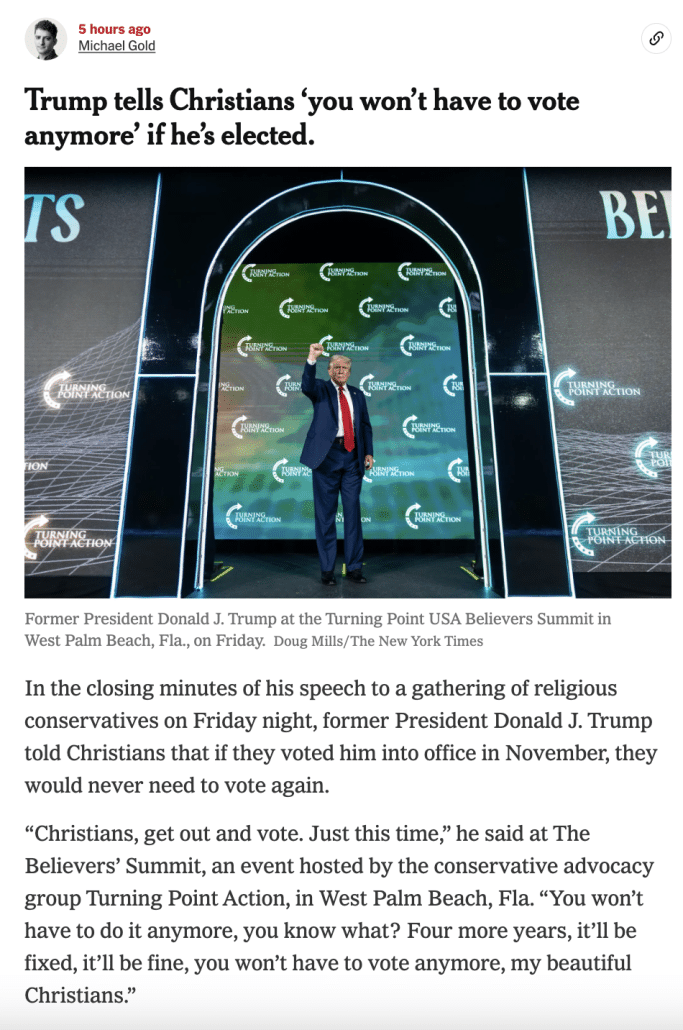

But once their chat began, 40 minutes after it was scheduled, Mr. Musk’s and Mr. Trump’s newly developed camaraderie was on clear display, with the billionaire tech entrepreneur lobbing softball questions that allowed Mr. Trump to rattle off the talking points that have animated his presidential campaign.

The conversation offered little new information about Mr. Trump’s views. Over the course of more than two hours, Mr. Trump attacked Vice President Kamala Harris, his Democratic opponent, as a “phony” who, along with President Biden, failed to address crossings at the U.S. border with Mexico. He repeated a number of false claims, including that the 2020 election was rigged, the criminal cases against him were a conspiracy by the Biden administration to undermine his candidacy and the leaders of other nations were deliberately sending criminals and “their nonproductive people” to America.

Sure, like WaPo, eight paragraphs later, he contrasted that to the NABJ appearance. But he also suggested that poor Mr. Trump grew frustrated at his own press conference.

Last month, Mr. Trump was combative while being interviewed by a panel of Black female journalists at a National Association of Black Journalists convention, where he questioned Ms. Harris’s racial identity. Last week, he grew frustrated by questioning at a hastily scheduled news conference in Palm Beach, Fla., where his answers often meandered and a story he told about a helicopter ride drew significant scrutiny.

Apparently, Gold is so entranced with the three days NYT squandered by chasing down Trump’s false helicopter story he hasn’t figured out that it was no more than a vehicle for more lies about Kamala Harris.

Ultimately, though, the presser was the same: beset by technical problems created because journalists didn’t have mics, largely characterized by softball questions, and riddled with false claims.

Heck, even the combative (if you ignore Harris Faulkner) NABJ interview was also delayed, in part, by technical issues (though also Trump’s refusal to allow live fact-checking) and riddled with the same lies he keeps telling, including the attack on the authenticity of Kamala’s Blackness.

Gold complains that Musk’s conversation “offered little new information about Mr. Trump’s views.” But actual journalists could do no better. Importantly, Trump’s frustrations at the presser came in response to questions about crowd size and his flaccid campaign; Trump’s insecurities are nothing new.

The only thing that distinguished yesterday’s event from the one many mainstream campaign journalists validated with their participation is that Trump slurred his speech more yesterday.

My point is not that there’s some secret formula to elicit actual, truthful answers from Donald Trump. Trump doesn’t believe in truth; he believes in leveraging lies to exercise power. So no standard interview format will pin the man down.

Rather, it’s that journalists are indulging their own vanity by imagining they’re doing any better than Elon Musk.

Given that that’s the case — given that Trump’s attacks on the press have rendered them little more than props in his reality show — journalists ought to reflect on their own failures before they continue to screech that Kamala Harris, who in 23 days has vetted and picked a running mate, added key staffers, and done fairly epic campaign appearances in six swing states, has yet to offer a press conference to many of the same journalists who could do nothing more than make Trump squirm about crowd size.

I’m not saying a press conference with diligent journalists would not have value. I’m saying that if you struggle to distinguish the outcome of questioning from people being paid as professional journalists from what Elon Musk can elicit, your complaint is with the journalists, not Kamala Harris.

And until you fix that problem — until you fix all the inanity driven by a focus on the horse race rather than the outcomes — these journalists would offer little more than conflict narrative and drama if given the chance to question the Vice President about her campaign.

Update: In a piece calling on VP Harris to give a presser not because it’ll help but because it’s the right thing to do, Margaret Sullivan lays out all the inadequacies of journalists clamoring for one.

[W]hen the vice-president has interacted with reporters in recent weeks, as in a brief “gaggle” during a campaign stop, the questions were silly. Seeking campaign drama rather than substance, they centered on Donald Trump’s attacks or when she was planning to do a press conference. The former president, meanwhile, does talk to reporters, but he lies constantly; NPR tracked 162 lies and distortions in his hour-long press conference last week at Mar-a-Lago.

But Harris needs to overcome these objections and do what’s right.

She is running for the highest office in the nation, perhaps the most powerful perch in the world, and she owes it to every US citizen to be frank and forthcoming about what kind of president she intends to be.

To tell us – in an unscripted, open way – what she stands for.

[snip]

I don’t have a lot of confidence that the broken White House press corps would skillfully elicit the answers to those and other germane questions if given the chance. But Harris should show that she understands that, in a democracy, the press – at least in theory – represents the public, and that the sometimes adversarial relationship between the press and government is foundational.