The Other Things the Press Missed by Ignoring the Details Revealed in the Joshua Schulte Prosecution

The WaPo got a copy of the WikiLeaks Task Force report introduced as evidence in the Joshua Schulte from Ron Wyden’s office and so, four months after it was first made public, is declaring the scathing report “news”. (Note, WaPo does not reveal that InnerCity Press made this report public months ago after fighting for its release.)

If the report is news it’s a testament to all the news from the trial that didn’t get reported

The report is scathing. But it describes what any news outlet that covered the trial closely would have reported in real time (as well as the evidence that one after another Schulte denial had been contradicted by evidence submitted at trial), and as such is a confession that besides some passing coverage, few national security journalists did cover this trial and all its alarming disclosures.

The trial showed that Schulte tried to make sure 1TB of data got transferred properly in early May 2017 and then wiped two TB disk drives; this report from early in the investigation assesses that Schulte stole “at least 180 gigabytes to as much as 34 terabytes of information,” something CIA later got more certainty about. The government provided evidence that Schulte inserted outside CDs and thumb drives into his CIA workstation, made a copy of a months-old backup file, and set an Admin password for the files he is accused of stealing, which is why the report focuses so closely on the findings that, “users shared systems administrator-level passwords, there were no effective removable media controls, and historical data was available to users indefinitely.”

The report was published on October 17, 2017, weeks before WikiLeaks published the source code for Hive on November 9, 2017, making this claim (though not necessarily the assessment that Schulte didn’t get the “Gold File”) out of date:

To date, WikiLeaks has released user and training guides and limited source code from two parts of DevLAN: Stash, a source code repository, and Confluence, a collaboration and communication platform. All of the documents reveal, to varying degrees, CIA’s tradecraft in cyber operations.

The trial showed that everyone from Schulte’s colleagues to then-CIA Executive Director Meroe Park had concerns about Schulte’s reliability, but none put him on leave or successfully cut off his access to the vulnerable systems, which makes this passage seem like a breathtaking understatement.

We failed to recognize or act in a coordinated fashion on warning signs that a person or persons with access to CIA classified information posed an unacceptable risk to national security.

The trial also showed that the CIA waited almost two years after this report to put “Michael,” Schulte’s CIA buddy who testified to seeing him stealing files in real time, on paid leave, making it clear they didn’t address this issue even though it appeared in the report.

The report also doesn’t include unredacted descriptions of how the leak led all of CIA’s hack-based spying to grind to a halt, such as that offered by Sean Roche, who had been Deputy Director of the Directorate for Digital Innovation.

Our capabilities were revealed, and hence, we were not able to operate and our — the capabilities we had been developing for years that were now described in public were decimated. Our operations were immediately at risk, and we began terminating operations; that is, operations that were enabled with tools that were now described and out there and capabilities that were described, information about operations where we’re providing streams of information. It immediately undermined the relationships we had with other parts of the government as well as with vital foreign partners, who had often put themselves at risk to assist the agency. And it put our officers and our facilities, both domestically and overseas, at risk.

[snip]

Because operations were involved we had to get a team together that did nothing but focus on three things, in this priority order. In an emergency, and that’s what we had, it was operate, navigate, communicate, in that order. So the first job was to assess the risk posture for all of these operations across the world and figure out how to mitigate that risk, and most often, the vast, vast majority we had to back out of those operations, shut them down and create a situation where the agency’s activities would not be revealed, because we are a clandestine agency.

Nor does the October 2017 report include details about the exploits — such as that these tools were USB drives that NOCs and/or assets would stick into target computer systems, making it likely the leak endangered people who had used the tools — that provide some idea of the kinds of damage the leak did.

Schulte claims the “classified” information on his server consisted of Snowden documents

Meanwhile, there have been several updates in the government’s attempt to retry Schulte.

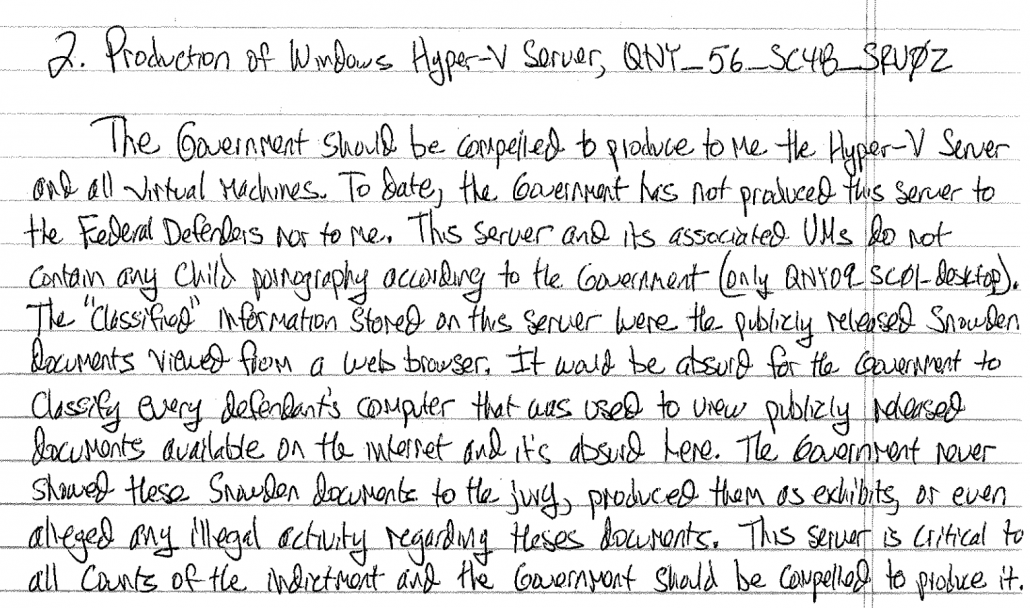

First, on May 21, the court docketed a hand-written letter from Schulte to Judge Paul Crotty, dated April 12. In it, he claimed He had no counsel,” which is confusing because he has appeared in court subsequent to the letter and its posting with the same trial team (though in a recent filing, his lawyers said Steve Bellovin may not be available to serve as expert in his retrial). Based on his claim to have no lawyers, he asked for access to a bunch of things withheld in discovery, a number of which are things his lawyers had tried but failed to obtain already. That includes his own server, which (according to Schulte, who has proven utterly unreliable) the government withheld because it held “classified” information consisting of the publicly released Snowden files.

The claim is interesting in any case. If Schulte viewed the files while still at CIA, it would be a violation of the government’s ridiculous claims that clearance holders could not view those files without violating their clearance. It’s also interesting given Schulte’s claims, to colleagues, that Snowden should be executed, even while saying elsewhere that Snowden didn’t harm anyone.

The government floated — and then did not fully develop (possibly as part of an agreement to avoid a subpoena to Mike Pompeo) a theory about Schulte’s ties to other leaks, including Snowden’s. That makes the fact they’re still sitting on these files far more interesting. (Schulte used the reports about the hacking of Angela Merkel in his defense.)

DOJ’s superseding indictment tries to make the retrial easier to win

Then there are the circumstances surrounding a third superseding indictment obtained against Schulte on June 8 (which the WaPo notes but doesn’t explain). As the government had explained, they got the indictment to make the specific allegations more clear for the jury than the second indictment, which was released before CIA had declassified the things used at trial.

These counts are based on the same conduct that was at issue during the February trial, namely, the defendant’s theft and transmission of the Backup Files, his destruction of log files and other forensic data on DEVLAN in the course of committing that theft, his obstruction of the investigation into the leak of the Backup Files, and his transmission and attempted transmission of national defense information while detained at the MCC. The modifications in the Proposed Indictment, however, are intended to make clear what conduct is covered in the specific counts. Thus, the Proposed Indictment (i) contains two separate § 793(e) counts related to (1) the defendant’s transmission of writings containing national defense information from the MCC and (2) the defendant’s attempted transmission of writings containing national defense information from the MCC, whereas the S2 Indictment grouped that conduct together in a single count; (ii) clarifies that all the § 793(e) counts, pertaining both to the transmission of the Backup Files and the defendant’s conduct in the MCC, charge the transmission of documents and writings, which does not require proof that the defendant had reason to believe the information therein could be used to harm the United States; (iii) contains two separate § 1030(a)(5)(A) counts specifying that the charged harmful computer commands at issue are (1) the defendant’s manipulation of the Confluence virtual server and (2) the defendant’s log deletions, whereas the S2 Indictment grouped that conduct together in a single count; and (iv) lists the false statements underlying the obstruction charge, which had previously been identified for the defendant in a bill of particulars, whereas the S2 Indictment did not do so.

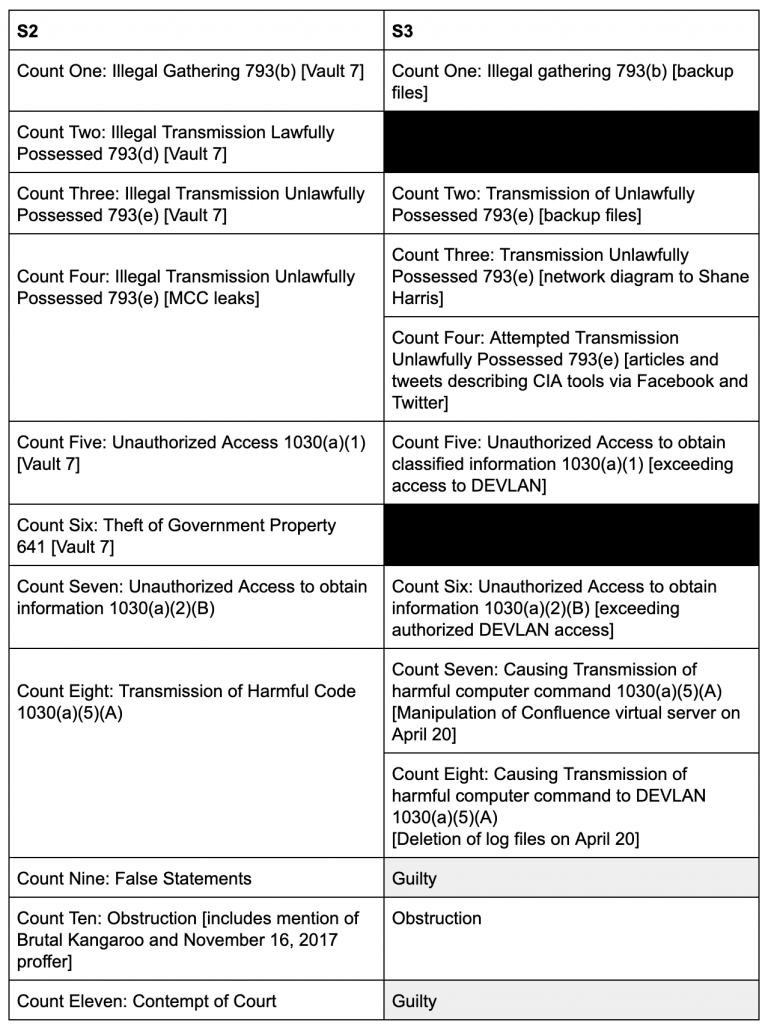

Here’s a table that shows the difference between the second superseding indictment and the new one.

The government had dropped Count Two during the trial to make it clear that Schulte was exceeding his access when he stole the files he allegedly sent to WikiLeaks. And Schulte had challenged the 641 charge on legal grounds, which explains the dropped charges (marked in black). Jury questions had made it clear that jurors were fighting over what Schulte leaked and tried to leak from jail, and couldn’t agree upon whether Schulte’s various manipulations of the backup servers amounted to a crime. By turning each into two charges, the government not only tells the jury precisely what to look for, but might even get prosecutors to focus on describing why the forensics prove the crime rather than describing the CIA’s personnel disputes. In other words, this superseding indictment is an effort to make it more likely Schulte will be found guilty for the actions described at trial.

Meanwhile, whereas elsewhere the new indictment aims to make things more explicit for the jury, the new one does not mention two things that were laid out in the bill of particulars laying out his false statements and obstruction in the second indictment: any reference to the Brutal Kangaroo tool that Schulte was working on at home and then may have brought back into work, and a discussion of a proffer session that took place on November 16, 2017 where Schulte falsely claimed to have been approached by an unknown male on the way to a court appearance. The government dropped the latter before Schulte’s trial. As to the former, it’s unclear whether the government has decided Brutal Kangaroo (which might have been used to help steal the files or unknown follow-up ones) is too sensitive to explain, or whether they want to make the obstruction charges more generalized.

Now that a bunch of journalists have effectively confessed they missed all this in real time, maybe they’ll finally get around to explaining why the government is having to revamp their charges to try they guy the CIA claims burned their hacking ability to the ground, which seems as newsworthy as this out-of-date, already published report.

Schulte doesn’t want a suburban jury

Nothing the government has done, however, will prevent jury nullification, which appears to have been a key factor in the first trial. Given the notes from the jury, at least two jurors seemed to be unwilling consider fairly clear evidence, and one of them hid that she had outside knowledge (comments she made publicly after she was dismissed suggested she believed Schulte’s claims that the government was using child porn to frame him for this leak).

Ultimately, prosecutors are going to have to explain to a NY jury why they should care that the CIA department in charge of hacking everyone else got hacked itself, all while Schulte’s lawyers make claims about what CIA does when it hacks that the CIA is not about to rebut publicly.

Which may explain why Schulte is preparing to challenge the circumstances of the most recent indictment. The grand jury on the most recent indictment is a White Plains one, not a Manhattan one.

The unusual circumstances of the S3 indictment—the grand jury was sitting in White Plains as opposed to Manhattan, and most members of the public in the Southern District of New York were still under a stay-at-home order—may have compromised the defendant’s right to a grand jury selected from a fair cross-section of the community. Accordingly, through this letter-motion and the accompanying declaration of statistician Jeffrey Martin, Mr. Schulte respectfully requests access to the records and papers used in connection with the constitution of the Master and Qualified Jury Wheels in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, pursuant to the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the United States Constitution and the Jury Selection and Service Act (“JSSA”), 28 U.S.C. § 1867(a) and (f).

While this motion to get records of how this jury was chosen may not lead to a challenge, ultimately, he seems prepared to argue that the pandemic prevented him from being tried by a jury of his peers. And that’s happening all while he’s refusing (as is his right) to toll Speedy Trial rights during the pandemic. (Plus, I’m not sure prosecutors are being very attentive to excluding the time that the defense itself has asked for.)

The press is only now waking up to what the trial (and the prior court filings) has shown. Perhaps now that they’ve tuned in they’ll bother to explain why the guy who allegedly burned the CIA to the ground may well get off on all his Espionage and hacking related charges?