About 26 pages into a 40-page indictment of Quanzhong An and his daughter Guangyang An — which was obtained last week but rolled out at a press conference yesterday — the indictment shifts tracks dramatically.

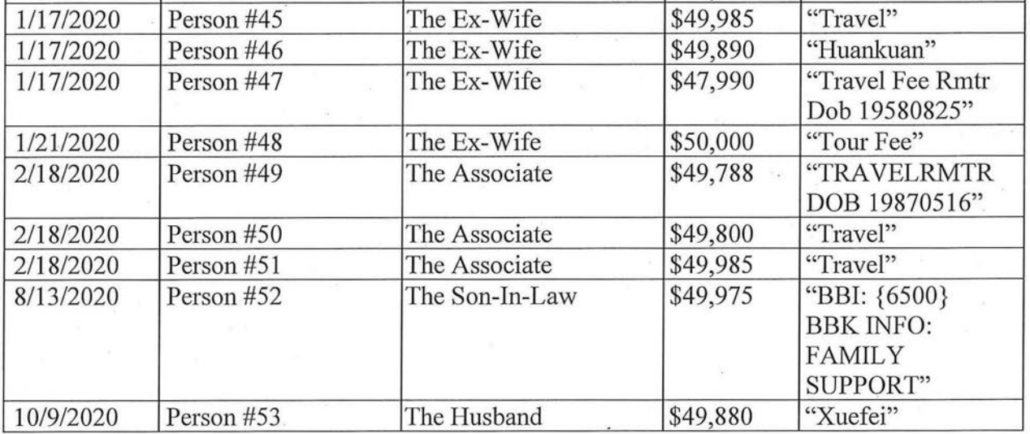

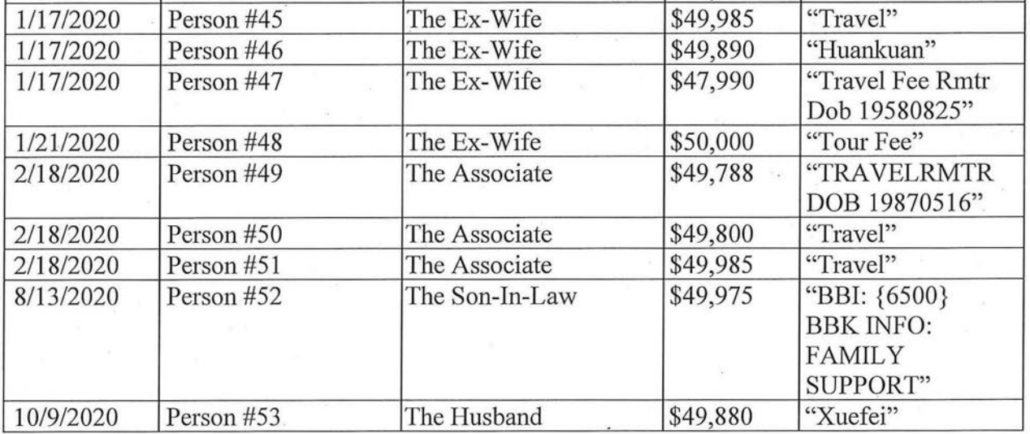

Up until that point, it lays out in detail An’s role in China’s efforts, dating back to 2002, to convince John Doe-1 and his son, referred to as John Doe-2 in the indictment, to return to China. But then at page 26, it starts to lay out alleged money laundering, showing how Quanzhong An transferred almost $4 million from China to the US over six years by transferring it in increments at or just under $50,000 in the name of family members.

From in or about 2016 through the present, the defendants QUANZHONG AN and GUANYANG AN conspired with others to engage in a money laundering scheme. During this period, the conspirators sent and caused to be sent millions of dollars in wire transfers from the PRC to the United States. As these activities violated applicable PRC law regarding capital flight — which imposed a limit of $50,000 per person annually for total foreign exchange settlement — the conspirators engaged in deceptive tactics designed to frustrate and impede the Anti-Money Laundering (“AML”) controls of the U.S. financial institutions, so that the defendants and the coconspirators could enjoy continued access to the U.S.-based bank accounts.

Here’s what a fraction of the transfers look like.

To be clear, the reason these transfers were made in $50,000 increments was to comply with Chinese transfer restrictions, not US ones. This is charged as money laundering in the US because (as the indictment notes) it involved false statements to banks and layering and other tactics to hide the ruse. But it also appears to be a violation of Chinese law, the same kind of law that the person targeted for repatriation by An allegedly violated.

As FBI Director Chris Wray noted at yesterday’s press conference,

Two of the subjects who targeted him, two of the defendants charged today, are themselves actually involved in a scheme to launder millions of dollars. And as if that weren’t enough evidence that the real purpose of their operation was political, they gave their victim a deadline to return by: the 20th CCP Congress earlier this month.

The money laundering belies the claim that China is pushing for John Doe-1’s repatriation out of some concern about financial corruption.

It may provide context, too, to details earlier in the indictment that described how An became involved in efforts to coerce John Doe-1 to return to China. As described, his efforts to lure John Doe-1 back to China started in 2017, when he showed up at John Doe-1’s home to locate him and his son. A year later, his daughter Guangyang accompanied a family member’s boss to the house in 2018, where they left a note and were captured on John Doe-1’s security camera, as shown in the picture.

In August 2019, one of the Chinese-based co-conspirators sent a message to John Doe-1 claiming that An was just helping out out of patriotism.

An Quanzhong is a patriotic businessman in the U.S. and the head of the Chinese Business Association of New York. He was originally from Zaozhuang, Shandong, and has given strong support to the government’s work. He is willing to communicate with [John Doe-1] and pay for [John Doe-1] to help the government recover the loss without anything in return. At the same time, he is willing to provide enough funds to guarantee [John Doe-1’s] return and cover his expenses needed to return home.

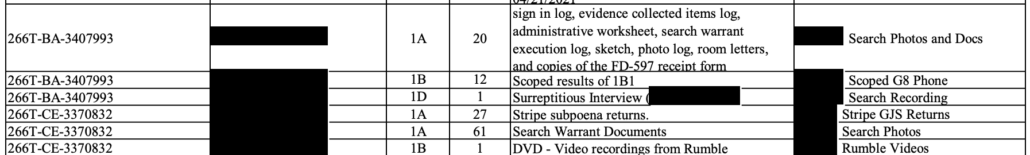

Starting in 2020, An started meeting with the son, John Doe-2, meetings which were consensually recorded (meaning either the FBI was already involved or John Doe-2 is really smart).

At a January 2020 meeting, An explained to the son what he was up to, admitted to the 2017 visit to the house, and explained that he would pay the money John Doe-1 allegedly owes to the Chinese state and put him up in his Chinese home if he returned. John Doe-2 asked why he was willing to pay that amount, and An explained that he was trying to get the Chinese government to view him as a good guy.

QUANZHONG AN responded that he had donated over 100 million yuan to the PRC government the previous year and that the PRC government “will be very happy if this thing is settle[d].” QUANZHONG AN boasted that, if he assisted with John Doe-1’s repatriation, the PRC government “will not see [QUANZHONG AN] as a bad guy because [he has] done so many good things, even donating money to society.”

In a July 2021 meeting with John Doe-2, also lawfully monitored, An repeated the promise that John Doe-1 would not be detained if he returned, then explained he was involved in part because of his business interests.

QUANZHONG AN also acknowledged how his business interests prompted his involvement in John Doe-1’s case. QUANZHONG AN explained, “[A]s you know, there are many ways to make it work in China. It’s hard to do business in China.” QUANZHONG AN claimed that he had succeeded by making donations to the PRC government. QUANZHONG AN further claimed that “he had donated over 300 million yuan over the years to the PRC government.”

In a July 2022 call that An brokered to take place at a hotel he owns in Flushing, one of the Chinese co-conspirators told John Doe-2 that he should return before the Party Conference (the October 20 arrest took place in the middle of it, which spanned from October 16 to October 22), because, “In case there is a change, I am afraid that it doesn’t work in favor of the old man” (which I believe is a reference to John Doe-1’s father, in China).

In recent weeks, the detention motion for the father and daughter describes, An met with John Doe-2 again, this time with a confession for John Doe-1 to sign in advance of the Party Congress.

More recently, Quanzhong An met with John Doe-2 again on September 29, 2022. During this meeting, Quanzhong An pressed for John Doe-1 to execute an agreement to return to the PRC in advance of the CCP’s 20th National Congress, which began on October 16, 2022. As part of such agreement, Quanzhong An sought a written confession from John Doe-1, which would be submitted directly to the PRC government. This morning, incident to Quanzhong An’s arrest, agents located a photograph of what appears to be a sample confession for John Doe-1 to use.

Instead of returning, the implication is, DOJ finalized this indictment on October 7, and the FBI arrested An and his daughter. The indictment includes two forfeiture provisions, and lists three properties. After his arrest last week, An was given a CJA attorney, suggesting the considerable assets he has in the US may be tied up in those forfeitures.

In other words, this appears to be a story of how the Chinese government used An’s own violations of Chinese law not to rein him in, but to coerce him to pursue the return of a long-sought exile. The US government is effectively using the leverage China had over An, because of his alleged money laundering, to impose far greater penalties — both financially and (because of stiff penalties on money laundering) in terms of criminal exposure — on his involvement in the matter here in the US.

This was one of three charging documents rolled out yesterday in a very high-level press conference involving Attorney General Merrick Garland, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco, National Security Division head Matthew Olsen, and FBI Director Chris Wray. Those three sets of charges are:

- Charging two suspected Chinese intelligence officers — both in China — who paid a double agent for what they believed was secret information pertaining to the 2018 prosecution of Huawei on racketeering charges. (press release)

- Charging four Ministry of State Security officers — all in China — in conjunction with their unsuccessful attempt to recruit a former law enforcement officer while on two trips to China (one in 2008, the second in 2018) and their successful recruitment of an unnamed and uncharged US permanent resident co-conspirator who took actions in New Jersey. (press release)

- As noted, the indictment charging US permanent resident Quanzhong An, his US citizen daughter Guangyang An, along with five Chinese based individuals, four of whom are members of the Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection for their efforts to lure a long-term US resident back to China. (press release, which was issued on the day of arrest, October 20)

On their face, the charges seemed quite unrelated (indeed, Wray acknowledged as much). On its face, the press conference seemed to be another of the showy ones designed to get attention precisely because most of those affected are overseas, out of the reach of law enforcement. (Compare that press conference to the more discreet rollout of the three indictments targeting Oleg Deripaska and his associates, charges that take more overt cooperation with other countries, to say nothing of even more juggling of ongoing sensitivities.)

Which raises the question of why now, why these cases. In response to a direct question about whether the timing of this related to the party conference — mentioned in the An indictment and in Wray’s prepared remarks — that solidified Xi Jinpeng’s third term, Wray said only that, “we bring cases when we’re ready.”

It may be that An was lured back to the US for his arrest based on that timing, which would in turn explain the timing of that arrest (which was announced, though not docketed, last week). But that would only explain why that case was rolled out, and it was already public last week.

An and his daughter are the only people described to be arrested in these documents.

But there is a Co-Conspirator-1 named in the New Jersey indictment (which was filed on October 20, the same day the An arrest took place) whose apparent US presence is unexplained in the indictment and yesterday’s press conference.

That indictment seems like it’s an investigation that started when a former law enforcement officer was recruited in China in 2008, which alerted the US government to the identity of Wang Lin, who in 2016 traveled to the Bahamas to begin recruiting CC-1, first by tasking him or her with delivering a $35,000 payment in the US. Then, in 2016, another of the co-conspirators, Wang Qiang, traveled with CC-1’s Chinese family members and had a series of discussions about working for China. In one, Wang expressed concern that the US had planted surveillance equipment on one of his phones at the airport.

During the same conversation, CC-1 also discussed with CC-l’s two family members, in sum and substance, what s/he believed to be the United States’ surveillance capabilities. CC-1 also told her/his family members that WANG QIANG had expressed concern when he (WANG QIANG) entered the United States that customs officials had installed surveillance equipment on one of his telephones at the airport, and that WANG QIANG was concerned about numbers for several contacts in North Korea that he had in his phones. CC-1 stated, in sum and substance, that WANG QIANG was “a low-level” official and should not have been concerned that he would be known to United States authorities.

It seems Wang was right to be concerned, because a series of damning conversations involving Wang and CC-1 were “lawfully recorded.”

WANG and CC-1 continued to discuss working on behalf of the PRC and obtaining information for the PRC in furtherance of its intelligence-gathering operations. Among other things, CC-1 stated thats/he “like(s) to do it,” meaning working for the PRC. CC-1 complained, however, that “[it] would be fine if there were more money.” CC-1 continued, stating, “It will work if you can truly pull off something big, things like the fucking U.S. high tech, anything that is important, right?” CC-1 then stated that “We are the ones who do the fucking work.” CC-1 also noted that “it is just a business,” that “they pay you for each job done,” and that “they will pay you again if they use you again.”

WANG QIANG and CC-1 continued to express fear about getting caught. Indeed, CC-1 stated thats/he did not “want to get into any trouble now.” CC-1 advised WANG QIANG, “If you don’t need to travel, it should be safe to stay in China. If you need to travel, fuck! The U.S. is very capable, I am telling you. You can’t run away from them.” CC-1 continued, “The Americans are really capable. Fuck! Two years or three years, screw you, they will get you when it’s time. . . . On the other hand, I have no use to them if I go back. I have no use to them if I go back to China.” During the conversation, WANG QIANG stated his belief that individuals working for the PRC “will be abandoned in the future.” [my emphasis]

There’s no other explanation for what happened with CC-1. And absent a 2018 offer to the law enforcement officer on a trip to China in 2018, these charges would be time-barred; I wonder whether that former law enforcement officer has a tie to the double agent described in the Huawei indictment (though timing wise, he cannot be the same person). Of that double agent from the Huawai case, Wray yesterday said, “we very rarely get a chance to publicly thank” double agents working in operations targeting China and other foreign countries.

But the pattern shown in the An indictment holds: the recruitment via Chinese associates using family ties of permanent residents in the US.

That is, at least two of these indictments appear to be based off far deeper investigative work than that FBI had previously pursued, in which they tried to catch scholars in false statements regarding dual Chinese and US-funding.

At yesterday’s press conference, someone asked (seemingly pointing to the ongoing threat of espionage from China), “Was it a mistake to get rid of the China initiative?”

The China Initiative was a Trump Administration effort that resulted in a series of high profile failed prosecutions and that sowed discrimination against Chinese and Chinese-Americans working in technical roles.

Garland responded by saying that,

These cases make quite clear we are unrelenting in our efforts to prevent the government of China from economic espionage, from operating in the United States as foreign agents, from trying to affect our rule of law, our judicial system, from trying to target or recruit Americans to help them … we have not in any way changed our focus on those kind of behaviors by China.

Olsen added,

We have stayed very focused on the threat that PRC poses to our values, to our institutions. We speak through our cases, and we speak to those cases today. I think what we are charging today in terms of the range and persistence of the threat that we see from the PRC demonstrates that we have remained relentless on that threat and we will continue to be focused on that threat going forward.

Asked by the same apparent Trump booster whether he had just gotten rid of the name, Olsen responded,

We ended the China Initiative earlier this year after a lengthy review and adopted a broader strategy focused on the range of threats that we face from a variety of nation-states, and that’s the strategy we’re carrying forward.

What DOJ spoke through its cases yesterday suggests they’re using longer-term operations to target a more fundamental recruiting effort and only unwinding them, one by one, as such interlocking efforts require it.

Update: In juggling some quotes I cut the part from which the title comes. I’ve added it back in (h/t higgs boson) and fixed another detail.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)