“True:” Hunter Biden Prosecutor Derek Hines Claims 80-Plus Equals “A Couple”

In Derek Hines’ reply to Hunter Biden’s opposition to prosecutors somewhat failed bid to substitute summary for proving authenticity of his digital data, Hines accused Abbe Lowell of misunderstanding the digital discovery in the Hunter Biden gun case.

In the remainder of his Response, defense counsel demonstrates (1) they still do not understand the electronic evidence in this case that they received in discovery last fall, and (2) despite claiming they do, they actually have no evidence to give them “reasons to believe that data has been altered and compromised before investigators obtained the electronic material.” Doc. No 151 at p. 1. None of what they claim in their Response is admissible in court, and the government objects to any line of questioning suggesting the trial evidence may have been manipulated because there is no foundation for such questions, they are also irrelevant, and even the inference posed by such a question risks confusing the jury.

As often happens with Mr. Hines (he of the sawdust-as-cocaine error), this seems to be a case of projection.

In an exchange with Judge Maryellen Noreika at last week’s status hearing, Hines suggested that the way to validate digital data that may have been in other people’s hands was to match the content of it to real world events: to tie Hunter’s observation that he was in Delaware to ATM withdrawals made by a guy notorious at Wells Fargo for losing his ATM card.

MR. HINES: Your Honor, one point of clarification I would like to add, too, if I may. So the summary chart, as Your Honor has read, summarizes stuff from Apple. John Paul Mac Isaac, has nothing to do with that data for that production.

THE COURT: I understood that. And as I understood, that’s where the real contest comes in, not from the iCloud, I guess unless the iCloud was backed up at some time during April.

MR. HINES: So it comes from two devices that Hunter Biden had, his phone and his iPad, that were backed up to Apple. John Paul Mac Isaac never had custody of that phone or the iPad at this store. He had the laptop. That stuff that is on the summary chart has nothing to do with what Mr. Lowell is alleging from The Washington Post. What we’re using on the laptop are messages that will be corroborated by a witness in this case who will testify that she sent those messages and received those messages and then a couple of other messages which we have noted on page 3 of our reply. Where there was other corroboration, for example, a message that shows that he’s in Wilmington, Delaware and made an ATM withdraw, that shows that as well. This isn’t some vast array of messages from John Paul Mac Isaac that the Defendant alleges without evidence that he planted into his laptop. To be clear, we’ve asked for reciprocal discovery over and over again. They made this claim in the media that the laptop wasn’t true. We haven’t seen one scintilla, not one message that that isn’t true from the data that law enforcement turned over. And they can’t raise that issue in any meaningful way at trial because there is no evidence of it. We want to make that clear in our reply, the data coming in, and we don’t believe there is any basis for Mr. Lowell to make these kinds of–

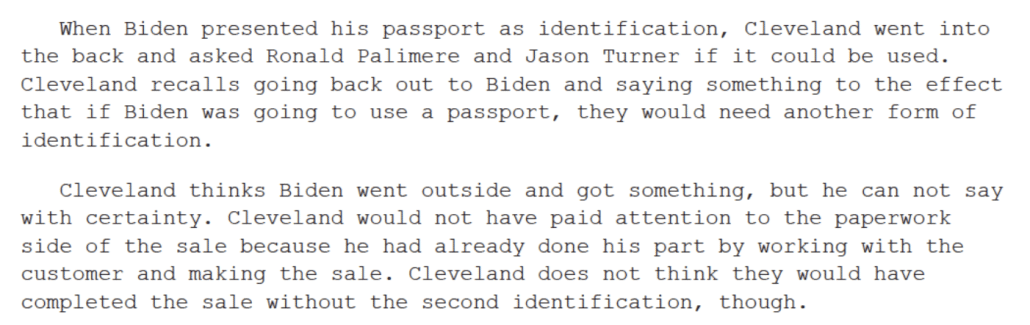

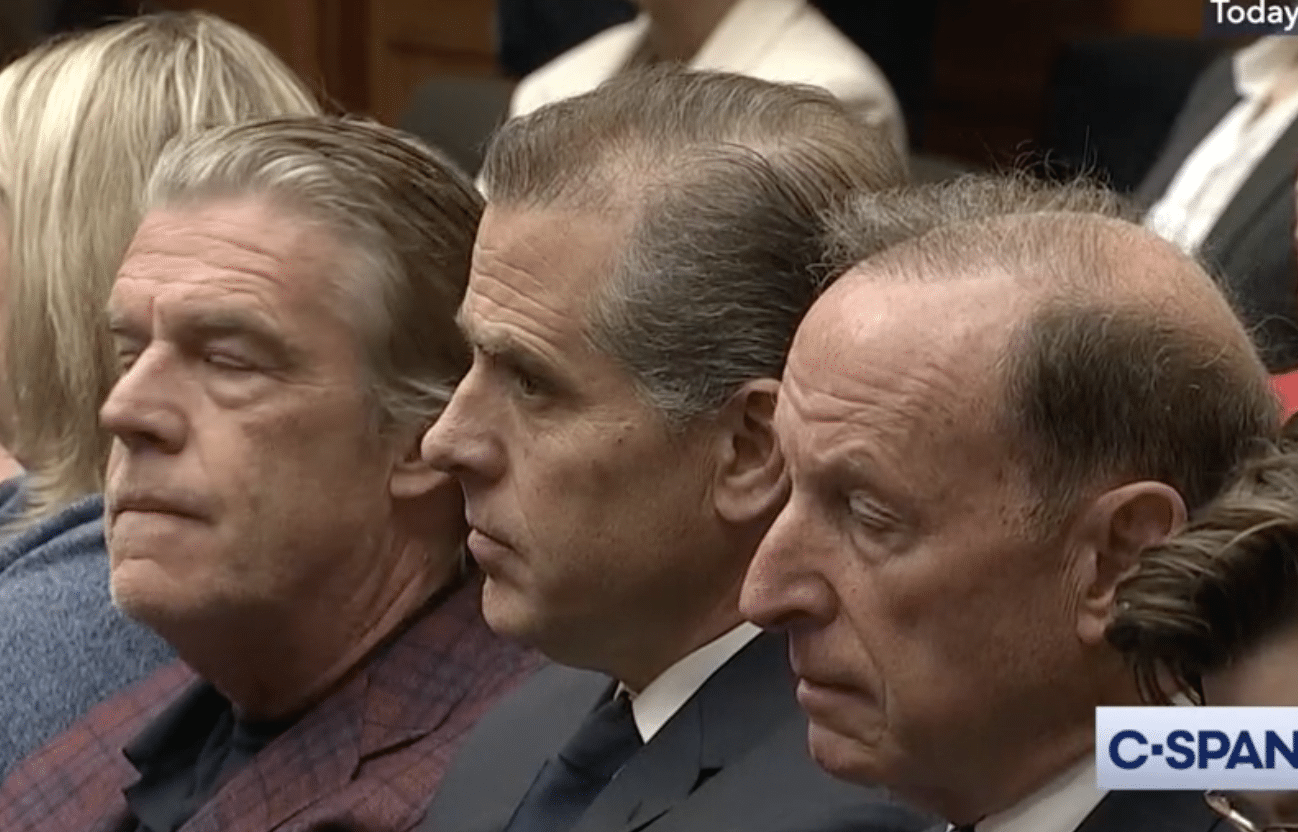

To be clear, if Hines is correct that Hallie Biden — the witness he promised, “will testify that she sent those messages and received those messages” — really will validate the messages she and Hunter exchanged in the days immediately after he bought a gun, the entire question of the authenticity of Hunter’s data should be moot.

That’s the most important evidence at trial, because it would (at the very least), show Hunter acknowledging his addiction and probably consuming drugs during the 11 days he owned a gun, going a long way to proving the strongest of three charges against the President’s son.

But David Weiss’ prosecutors are thinking bigger than that.

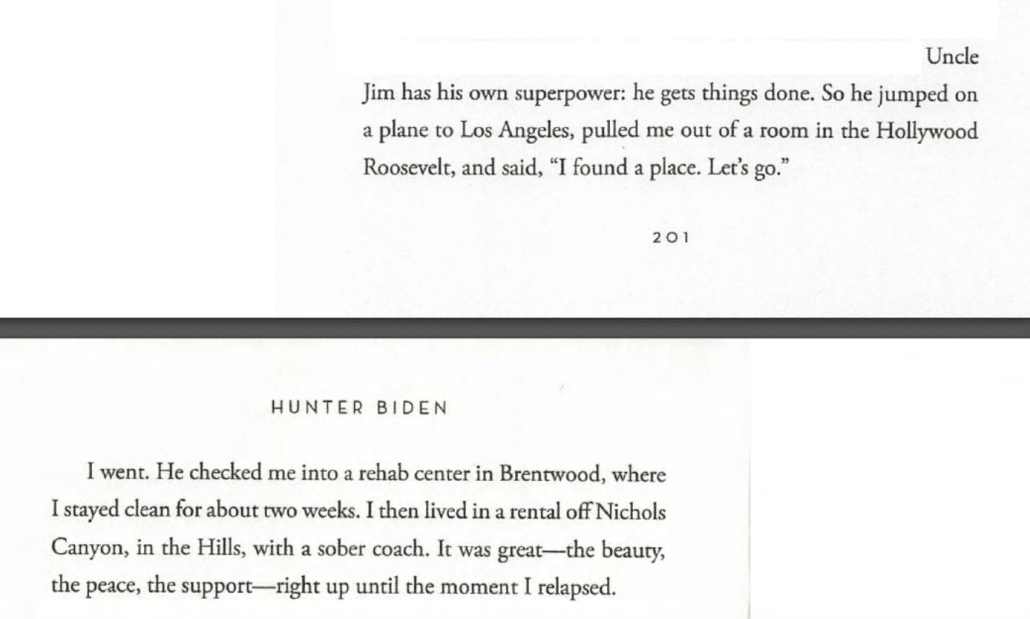

They’re obsessed with the bacchanalia Hunter had during spring and summer 2018 in Los Angeles, and plan to rely heavily on that — events that transpired before Hunter’s final attempt at recovery before he purchased the gun — to prove his addiction. And they keep claiming the state of Hunter’s addiction after Ketamine treatment from Fox News pundit Keith Ablow shows the state of his addiction in October 2018, when he owned a gun; again, they want to use memoir passages and texts from that period to prove the state of his earlier addiction. There are discontinuities in Hunter’s addiction that make those other periods less probative to the case.

And to submit this evidence, they’re seeking to admit a bunch of communications on either side of rehab attempts that won’t involve a counterpart to Hunter’s communications to validate them, as Hines promises Hallie will for communications during the period Hunter owned the gun.

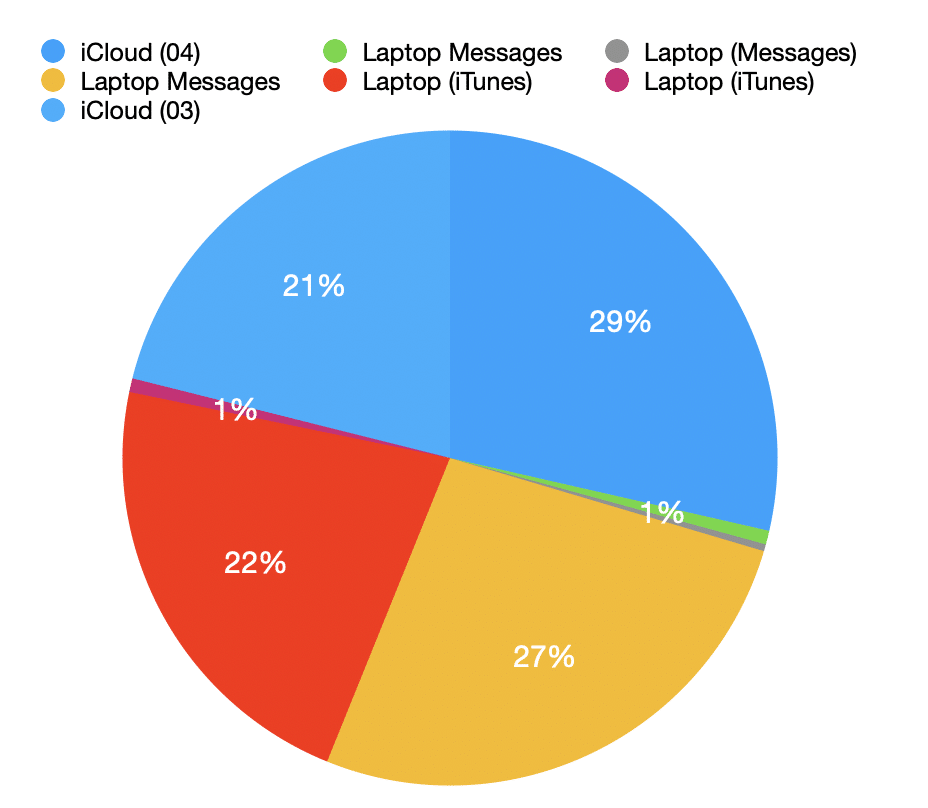

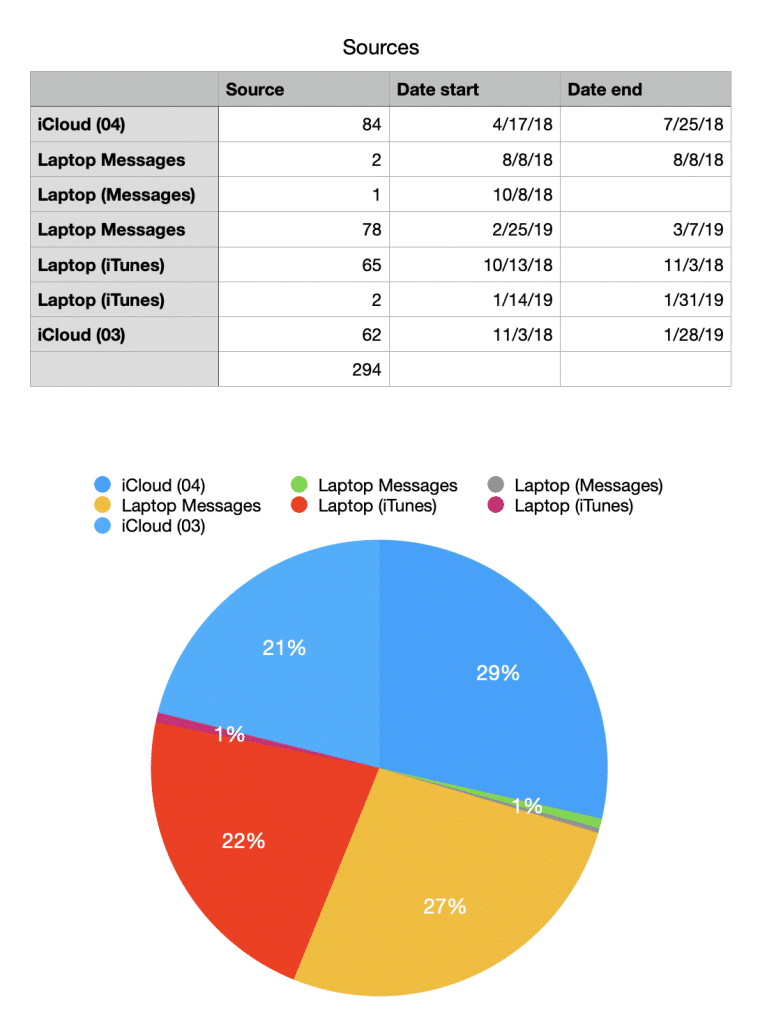

In this exchange Hines makes some misleading and one outright false claim. He seems to suggest to Judge Noreika that the summary chart only includes stuff from Hunter’s iCloud. He seems to suggest that none of the data in the summary chart went through John Paul Mac Isaac’s hands, when half of it did. Probably that’s just imprecision — a lack of specificity that just some of the messages were from the iCloud, that just some of the messages were from two devices that were backed up to Hunter’s iCloud.

But as to the claim that in addition to the messages that Hallie will validate, there are “a couple of other messages”?!?!

Here’s his description of the “couple” of messages noted on page 3 of the reply.

Messages in Row 85-86 (a message where the defendant says “I need more chore boy,” which is used consistently in the message with how the defendant described “chore boy” in his book), Rows 87 and 135-137 (messages where the defendant says he in Delaware, which is consistent with his ATM withdrawal activity, location information on photographs on his phone, and his admissions in his book), Row 214 (a photograph of the defendant with a crack pipe in his hand), and 216-292 (videos and photographs of the defendant with a crack pipe and drug messages from December to March 2019, consistent with the defendant’s characterization of his activity in his book).

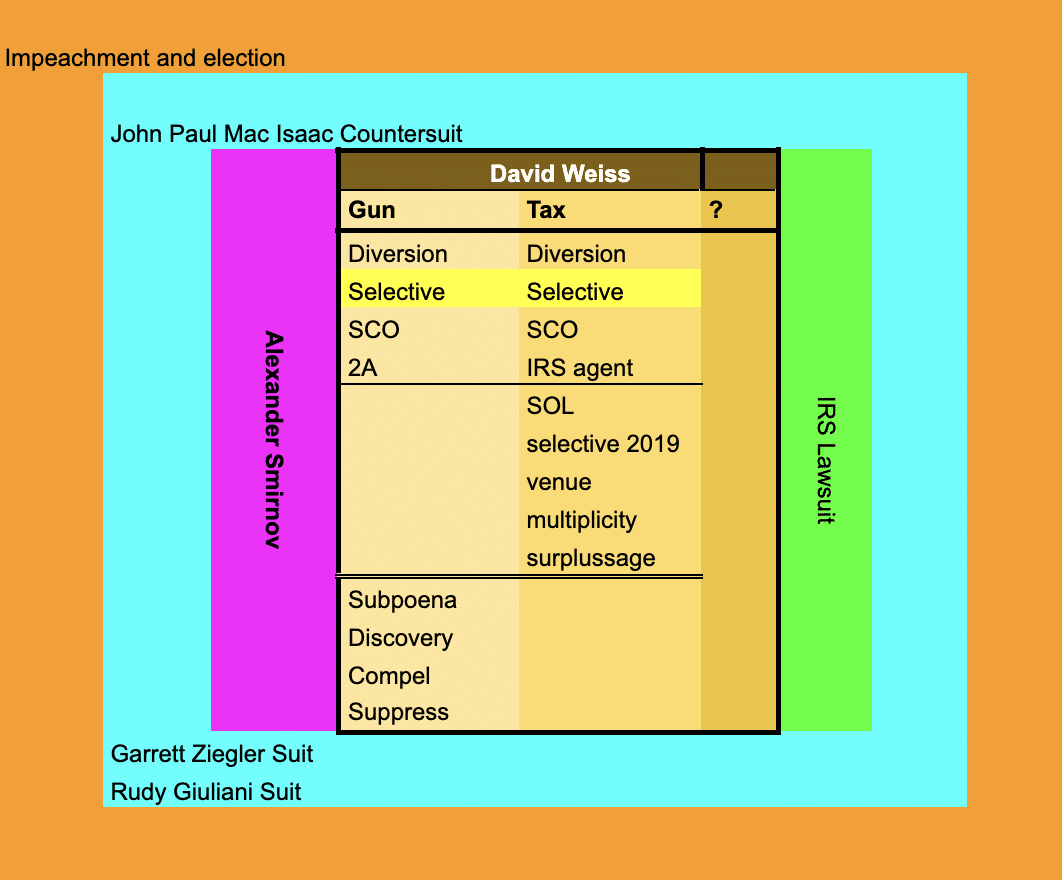

That’s upwards of 80 communications, and he may have excluded a few that don’t involve Hallie (this table breaks out various kinds of comms sourced to the laptop, partly to show outliers, partly to break out comms from the laptop that involve Hallie — marked in pink — and those that do not).

Eighty is not “a couple.”

Even among the texts exchanged with Hallie, I have questions about some, such as the November 3, 2018 text posted without any metadata and with a dark line (as if it came from some other table).

The January 28, 2019 text Hunter sent Hallie, describing that she threw his gun in a dumpster, will be another for which her validation will be key (and for which contextual texts may be pertinent).

I have questions about some of the stuff from iCloud, too — again, because the metadata suggests it does not reflect a backup taken of the device on which the content was captured.

But among the 80-plus other comms, several are presented without the kind of metadata that would make the reliable.

And that’s just what’s included in the summary chart.

Which gets me to the really curious part of Hines’ argument. Both at the hearing and earlier, he impatiently complained that Hunter’s team hadn’t provided any reciprocal discovery — meaning, something like the John Paul Mac Isaac deposition obtained as part of the lawsuit and countersuit (in which a decision has been pending since February). Hines seems to imagine that a witness testifying to altering documents would be the only basis on which Hunter could challenge the authenticity of the digital data prosecutors obtained, whether in public or at trial.

He seems not to have considered whether he already gave Hunter the evidence to challenge the authenticity of such data, using the very same techniques the FBI uses all the time in cybersecurity investigations: the metadata from about six different Hunter Biden accounts.

For his part, Abbe Lowell seems quite certain that some of the material in the FBI’s hands is not authentic. which is different than being confident that some of these communications are.

THE COURT: I understand, but do you disagree if he wants to ask, look, he dropped off the laptop in April, you got it in December, that he can ask that?

MR. HINES: He can ask that timing question, absolutely, Your Honor.

THE COURT: All right.

MR. LOWELL: And one more thing, Judge. I think there may be — I have no quarrel with the point if they have a witness that said I sent this or received this message, of course that’s fine. It’s just that it seems to me their point was they wanted a broad stroke agreement or stipulation that the data is all authentic as opposed to —

THE COURT: And can be tied to Mr. Biden?

MR. LOWELL: Yes. And so I can’t make that because we know to the contrary. I think your point about there might be individual things to raise, if we find that, we will, but I don’t have a disagreement with what you and Mr. Hines just said.

THE COURT: Okay. And I guess we can address that to the extent it comes up in trial. So as I understandit, the government is asking for a ruling that the summary of voluminous messages is appropriate under the Federal Rule of Evidence 1006. Defendant doesn’t object to that. So I will allow this as a summary chart. The government is seeking to have this chart authenticated as of the date that the government received the laptop into federal — some federal agent’s custody. The Defendant does not disagree with that. So I will grant the motion to the extent that is what the motion is seeking.

With respect to whether particular messages on there can be challenged, we will have to take that on a case-by-case basis at the trial.

MR. HINES: Your Honor, on point two that you just read for your ruling, it’s the laptop and the Apple iCloud because the Apple iCloud came into the custody of law enforcement independently of the laptop. I wanted to make sure that was our request as well.

THE COURT: Thank you for that clarification.

MR. LOWELL: One other thing as to what you pointed out in terms of the book. We raised the issue of completeness for their 1006 chart, which we will also talk to them about.

THE COURT: If there is stuff that you want to add.

MR. LOWELL: If not, we will proffer our own if we can’t agree. [my emphasis]

Notably, there has been no discussion of retired Secret Service Agent Robert Savage’s claims that Joseph Ziegler interviewed him based on what both Savage and Hunter claim were fabricated texts; those texts date to the same Los Angeles bacchanalia that Weiss’ team loves.

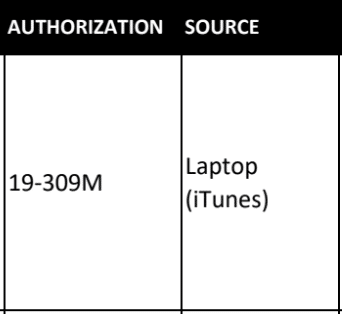

But being certain that there are some files in Hunter’s digital evidence (and Lowell appears to believe this is true of stuff saved to the iCloud as well) is different than being certain that certain of the communications prosecutors will rely on at trial are fabricated or planted. The import of all this will depend on how much it is — and whether and, if so, how well FBI Agent Erika Jensen, through whom prosecutors wanted to introduce this evidence by using summary in lieu of authentication, can answer questions about digital attribution. She’s likely playing this role because she is not privy to all the technical details about Hunter’s digital data.

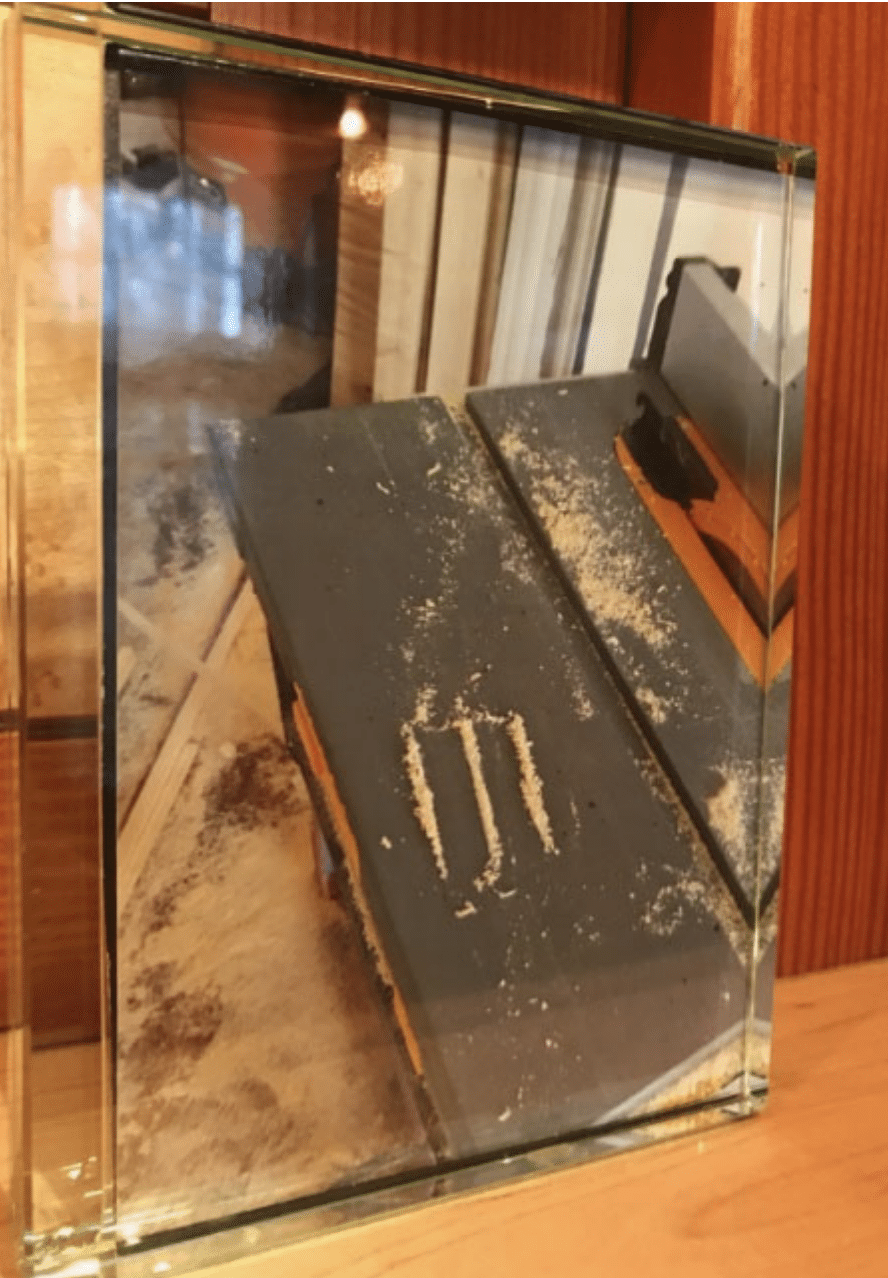

Perhaps the most remarkable part of this exchange, however, is that Hines measures this in terms of what is “true,” rather than whether it is “authentic.” “They made this claim in the media that the laptop wasn’t true. We haven’t seen one scintilla, not one message that that isn’t true.” But Hines has already proven that things he deems “true” may not be “authentic.” He claimed, as true, that a message sent by Keith Ablow was a true representation of Hunter’s (powder) cocaine use. Never mind that it was sawdust, not cocaine — that is, it wasn’t even “true.”

But it also wasn’t “authentic.” It wasn’t Hunter’s photo.

This is the mirror image of a logical problem that right wing propagandists (and certain apologists for Russia have) about the laptop and about Russian hack-and-leak efforts: proving something’s authenticity as a way to dodge proving that an authentic message proves the truth claim they’re making. Here, Hines is simply skipping the authentication step (and he may well get away with it).

We shall see next week. Judge Noreika has left the door open to Hunter’s team challenging this digital data (contrary to what some of the reporting on the hearing claimed), and prosecutors have likely left themselves open to more significant challenges by including data that is less probative to their case than the texts Hallie can validate herself.

At the hearing, Judge Noreika also left open the possibility of Hunter submitting on full pages from his memoir, not just the excerpts picked by prosecutors (though her order may be limited to pages, not longer passages).

[T]he motion will be granted in part. The pages offered by the government may be admitted, but the motion is denied to the extent that the government seeks to admit a page from Defendant’s memoir without giving him the opportunity to seek the admission of additional relevant sentences or passages from that same page subject to the Rule of Completeness so long as the statements made meet other requirements for relevance and prejudice. The excerpts by the way still need to come in through a witness.

Now, that being said, I will note that no one has provided me with un-redacted pages from the book, so I can’t tell you at this point whether I view any of the redacted portions to be properly admissible on the Rule of Completeness or the relevance and prejudice, but I do think it’s unfair that Defendant wouldn’t be given an opportunity to establish that.

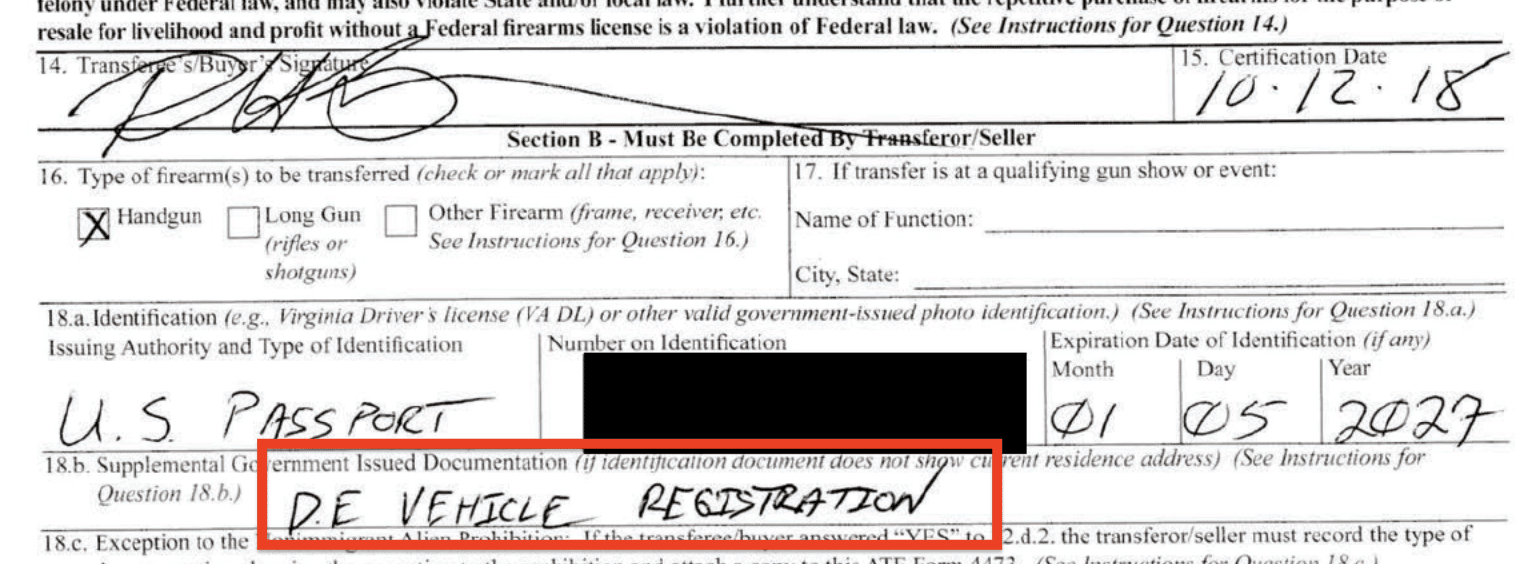

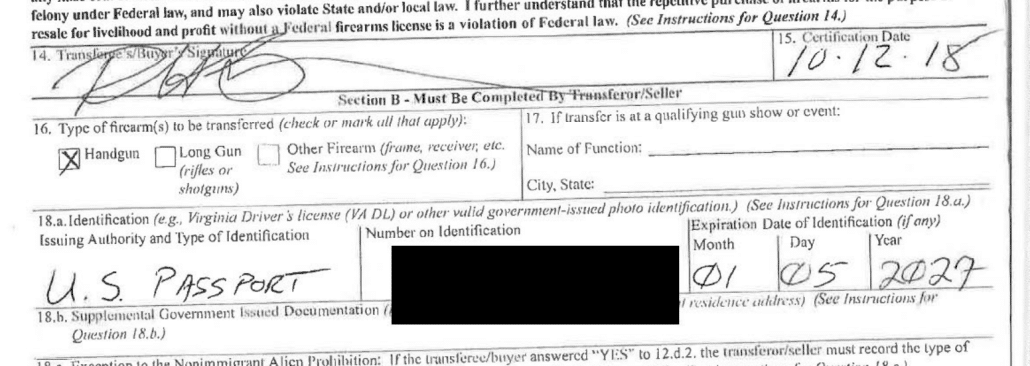

She has yet to rule on the ATF form doctored after the fact by the gun shop. But Derek Hines did, at least, provide a non-responsive explanation for the source of the three colors on the form.

THE COURT: So you are planning to call Mr. Cleveland. And he is going to say I watched the Defendant fill out the form. I wrote down — did he write down — I noticed that with Mr. Lowell’s motion, he gave me a color copy of the form, which was nice. So is he going to be able to testify who wrote stuff in red, blue, black, whatever?

MR. HINES: Yes, he will. He will testify that Mr. Biden filled out Section A, which is the section that can only be completed by the buyer. And he will testify that he signed the form. You can see his signature on the third page of the form. And then he will testify that Jason Turner filled out Section B of the form. Jason Turner is another employee of StarQuest.

THE COURT: And who filled out — oh, Section B.

MR. HINES: Correct, Section B.

THE COURT: It looks like the same person who makes their zeros like that, but some are in black and some are in red.

MR. HINES: Correct. Based on the information the government has, he will testify that Mr. Turner completed Section B of the form.

Again, prosecutors have a strong case against Hunter Biden. But two of three ways in which they attempted to mitigate the holes in their case have at least partly failed.

Update: Corrected date of November 3 text.