Democracy Against Capitalism: Conclusion Part 1

Index to posts in this series.

I didn’t see a precise definition of capitalism in Democracy Against Capitalism by Ellen Meiksins Wood, though it’s obvious Wood is talking about capitalism in the UK and the US. Here’s a definition I found in a 2006 paper by Bruce R. Scott, the Paul Whiton Cherington Professor of Business Administration, Emeritus at the Harvard Business School. The paper is titled The Political Economy of Capitalism.

Scott offers this definition of capitalism taken from the Palgrave Dictionary of Economics:

Political, social, and economic system in which property, including capital assets, is owned and controlled for the most part by private persons. Capitalism contrasts with an earlier economic system, feudalism, in that it is characterized by the purchase of labor for money wages as opposed to the direct labor obtained through custom, duty or command in feudalism…. Under capitalism, the price mechanism is used as a signaling system which allocates resources between uses. The extent to which the price mechanism is used, the degree of competitiveness in markets, and the level of government intervention distinguish exact forms of capitalism. P. 2-3, fn. omitted.

He comes up with a slightly different definition, and I’ll come back to this paper in another post. I doubt this definition would be acceptable to Wood, because it hides the reality of capitalism. For example, it says that in feudalism, one class “obtains” labor from another, which is probably not how peasants experienced it. She would at least state that almost all social systems enforce some form of expropriation by a dominant class, and discuss the mechanisms of that domination and expropriation in capitalism. She would want to discuss the logic that operates in capitalism, which I take to be something like this.

a. The goal of individual capitalists is to increase the amount of capital under their control.

b. The point of capitalism as a system is to produce returns to capital. Those returns come from producing goods and services for sale at a profit.

c. Capitalists only produce goods and services for sale. Capitalists produce nothing that cannot be sold for a profit.

d. Any means that can be used to increase the returns to capital will be supported by capitalists. These include cheating on taxes, use of tax havens, pollution, screwing workers, supporting tax cuts and tax advantages for capital (lower capital gains rates, ending Estate Taxes, lower marginal rates, special depreciation rules, outright exemptions for certain types of income, extortion of state and municipal governments for tax benefits), fighting unions, bribing legislators, regulators and executive branch officials, the list is endless and as far as I know has never been assembled in one place.

These four points aren’t laws, in the sense of the laws of physics. They are simple observations of the actual behavior of the capitalist class. They paint a bleak picture of capitalism, utterly unlike the way capitalism is portrayed in the media, by the government, by politicians, by educators and even by religious leaders. Wood argues, essentially, that any benefits it confers were forced by workers or governments, and are under constant assault. Violations of laws by capitalists are never punished as the serious crimes they are. Which executive of BP, Transocean or Halliburton went to jail for blowing up a drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico, killing 11 people and poisoning the waters? No one is accountable for the damage done by capitalists behind the corporate shield, whether to the environment or to the people they employ.

I’ve gotten in the habit of referring to our current system of capitalism as neoliberalism, but for Wood, the capitalism we see today is just the logical growth of capitalism as Marx predicted, following the logic described above. When Marx wrote, capitalism had a solid foothold in England, but it had yet to reach its full extension. In both England and the US there were many artisans and free farmers who owned their own means of production, and were free from the imperatives of the marketplace. They had the ability to feed and shelter their families with little or no recourse to a market economy. They were for the most part free to sell or retain their production for their own use. Outside of Europe and the US, pre-capitalist economies were the dominant form.

That is no longer the case. It is very difficult for any not-rich person to provide for themselves and their families without selling their labor to capitalists. That is just as true of software engineers as it is of doctors and plumbers. No one, even the rich, can provide the necessities of life without using markets.

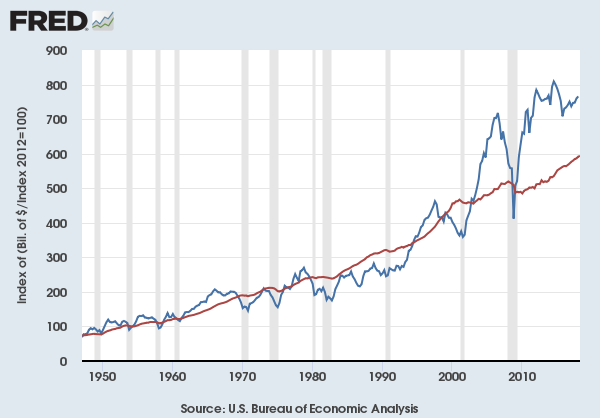

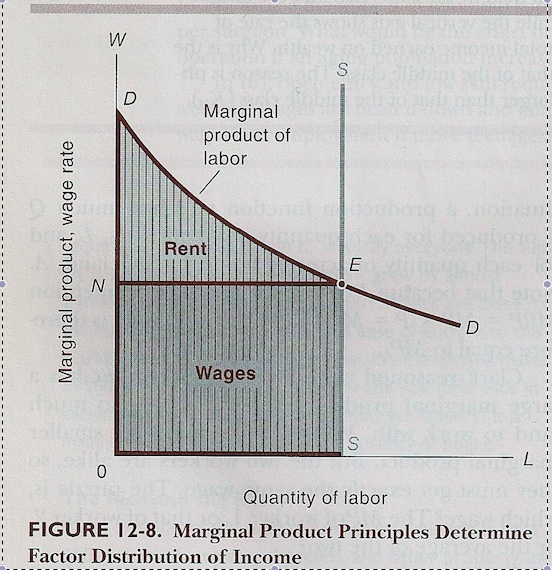

Wood argues that we have nearly reached the situation Marx predicted: a society of two classes, capitalists and producers. The capitalists provide some level of sustenance to those they hire, and the rest are dependent on the state or they are on the street. Or they die. The difference between the value produced by workers and their pay is sucked up by the capitalists. Although Wood doesn’t mention it, the financial sector eats up some of the sustenance received by the workers. All of us are forced to participate in a system dominated by the rich.

This system is supported by neoliberalism, an ideology dreamed up by economists and other academics. There is no point of contact with democracy. In fact, there is good reason to think that neoliberalism would work better in an autocracy or an aristocracy, and some conservatives, such as the New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, think the 17th Amendment (direct election of Senators) should be repealed as a step in that direction.

The main goal of neoliberalism is to provide a theoretical basis for denying governments the power to interfere with the business activities of capitalists, an utterly anti-democratic goal. Most people spend a huge part of their time working and commuting to work, and thinking and worrying about work. Corporations now make decisions that have massive impacts on individual lives, and on society, with little or no input from government or non-rich individuals or society, and regardless of whether they serve any purpose that outweighs the damage. It’s absurd to say that the bulk of our lives should be controlled by the decisions of the rich and powerful with no democratic control. But it’s just fine under neoliberal theory. To be very specific, holders of private capital have created the current planetary environment, which is rapidly becoming inhospitable to human life. A theory that supports their efforts to do so is suicidal.

As I say, it’s a bleak picture. In the next part I look at a somewhat less somber picture.