For years, Ron Wyden and Mark Udall have been calling the secret interpretation of Section 215 “secret law.”

I’ve always thought they meant that figuratively. The law got made by the FISA Court in secret, but there’s an opinion there somewhere, laying out the interpretation of the law. It’s just secret.

Ever since the release of the first documents responsive to the EFF/ACLU FOIAs, I’ve begun to wonder. What we’ve seen include:

Neither of those were comprehensive. And the “supplemental opinion” would seem to suggest it supplemented … something.

Yesterday, we got what appears to be a (shoddy) comprehensive opinion.

That opinion cites an earlier opinion from the FISA Court that is not, however, cited in either the 2006 or 2008 opinions. That earlier opinion examines how bulk collection affects the Fourth Amendment.

Here, the government is requesting daily production of certain telephony metadata in bulk belonging to companies without specifying the particular number of an individual. This Court had reason to analyze this distinction in a similar context in [redacted]. In that case, this Court found that “regarding the breadth of the proposed surveillance, it is noteworthy that the application of the Fourth Amendment depends on the government’s intruding into some individual’s reasonable expectation of privacy.” Id. at 62. The Court noted that Fourth Amendment rights are personal and individual, see id. (citing Steagald v. United States, 451 U.S. 204, 219 (1981); Rakas v. Illinois, 439 U.S. 128, 133 (1978) (“‘Fourth Amendment rights are personal rights which … may not be vicariously asserted.,) (quoting Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S. 165, 174 (1969))), and that “[s]o long as no individual has a reasonable expectation of privacy in meta data, the large number of persons whose communications will be subjected to the … surveillance is irrelevant to the issue of whether a Fourth Amendment search or seizure will occur.” Id. at 63. Put another way, where one individual does not have a Fourth Amendment interest, grouping together a large number of similarly-situated individuals cannot result in a Fourth Amendment interest springing into existence ex nihilo.

[snip]

Furthermore, for the reasons stated in [redacted] and discussed above, this Court finds that the volume of records being acquired does not alter this conclusion. [my emphasis]

Note while this pertains to metadata, there’s no indication it addressed phone metadata.

Later, it cites two earlier FISC cases.

This Court has previously examined the issue of relevance for bulk collections. See [6 lines redacted]

While those involved different collections from the one at issue here, the relevance standard was similar. See 50 U.S.C. § 1842(c)(2) (“[R]elevant to an ongoing investigation to protect against international terrorism …. “). In both cases, there were facts demonstrating that information concerning known and unknown affiliates of international terrorist organizations was contained within the non-content metadata the government sought to obtain. As this Court noted in 2010, the “finding of relevance most crucially depended on the conclusion that bulk collection is necessary for NSA to employ tools that are likely to generate useful investigative leads to help identify and track terrorist operatives.” [my emphasis]

Both, apparently, relied on the Pen Register statute, not Section 215, and one was fairly recent (2010 — perhaps that’s the geolocation one?).

But it appears not to reference an earlier Section 215 phone metadata case, not even to lay out the rationale for relevance and bulk collection.

In addition to references to these earlier apparently non-215 phone data precedents, Eagan also cites the government’s 2006 Memorandum of Law.

Accompanying the government’s first application for the bulk production of telephone company metadata was a Memorandum of Law which argued that “[i]nformation is ‘relevant’ to an authorized international terrorism investigation if it bears upon, or is pertinent to, that investigation.” Mem. of Law in Support of App. for Certain Tangible Things for Investigations to Protect Against International Terrorism, Docket No. BR 06- 05 (filed May 23, 2006), at 13-14 (quoting dictionary definitions, Oppenheimer Fund, Inc. v. Sanders, 437 U.S. 340, 351 (1978), and Fed. R. Evid. 4012°).

Normally, a judge would cite a precedential opinion, showing that another judge had agreed with such definitions. Not here. Eagan cites the government’s own memorandum for the definition for relevant. (She cites that memorandum at least two more times in her opinion.)

Which seems to suggest this 2013 opinion — one written after widespread leaks of the program — constitutes the first opinion systematically rationalizing this program.

Well over 7 years after it started.

There’s one more detail that seems to support this conclusion. The White Paper describes how the Administration shared significant FISC materials with the Intelligence and Judiciary Committees.

Moreover, in early 2007, the Department of Justice began providing all significant FISC pleadings and orders related to this program to the Senate and House Intelligence and Judiciary committees. By December 2008, all four committees had received the initial application and primary order authorizing the telephony metadata collection. Thereafter, all pleadings and orders reflecting significant legal developments regarding the program were produced to all four committees.

So in 2007 DOJ started providing “all significant pleadings.” By the end of the following year — perhaps not coincidentally, the same month Walton wrote his supplemental opinion — the committees got “the initial application and primary order.”

The initial application (including, presumably, that same 2006 Memorandum of Law cited by Eagan) and the primary order, the same order we got last week. No mention of the initial opinion.

It appears there is no initial opinion.

One more detail that I’ve mentioned, but bears mentioning again. The judge that appears to have allowed the government to start collecting the phone records of every American without laying out his legal rationale for allowing them to do so, Malcolm Howard? He served as Deputy Special Counsel in the Nixon-Ford White House, when a young Dick Cheney was learning the ropes as Assistant to the President and then Chief of Staff.

Perhaps they learned the ropes together?

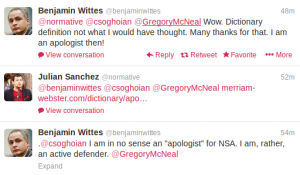

Update: Remember how the White Paper had to dig up an outdated version of the OED to support its definition of “relevant”?

the Administration decided to use a 24-year old edition of the Oxford English Dictionary for this definition.

Standing alone, “relevant” is a broad term that connotes anything “[b]earing upon, connected with, [or] pertinent to” a specified subject matter. 13 Oxford English Dictionary 561 (2d ed. 1989).

Note, that appears to be the same one used in the 2006 Administration Memorandum of Law. There’s nothing that surprising about that — I suspect substantial parts of the White Paper were lifted from that Memorandum.

But it is the kind of thing both Malcolm Howard and Claire Eagan might have challenged — and an adversary probably would have.

It appears neither did. Which is just one measure of the degree to which those judges simply rubber stamped whatever the government put before them.