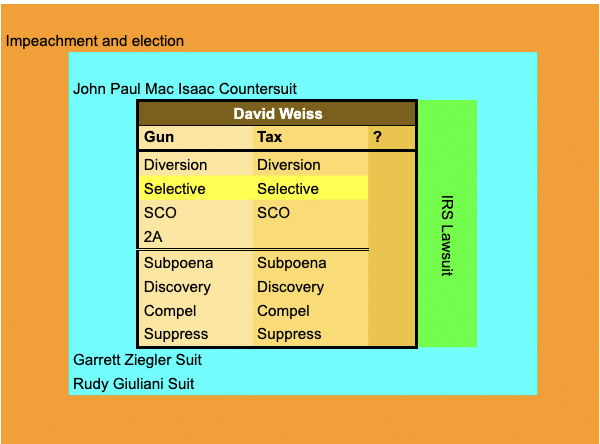

On Friday, David Weiss submitted most of his responses to Hunter Biden’s Motions to Dismiss in the Los Angeles tax case (he should submit a response to Hunter’s claim that the disgruntled IRS agents’ media tour amounted to a gross violation of his due process today; see links for everything here).

Expect a few posts going through them in the next few days.

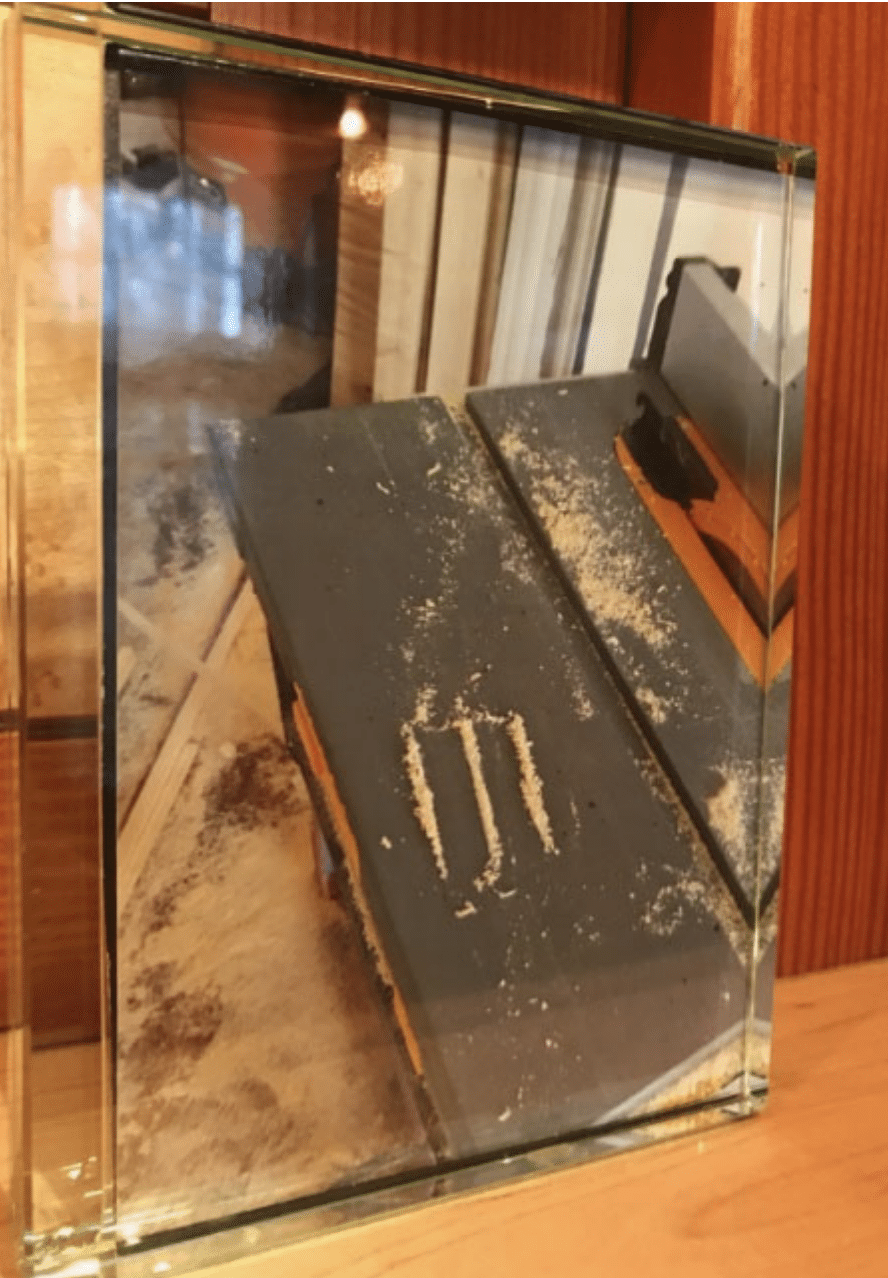

Start with another embarrassingly false claim Weiss made in response to Hunter Biden’s vindictive prosecution claim that is worse, in some ways, than claiming that Keith Ablow’s picture of sawdust was instead a picture Hunter Biden had taken of cocaine.

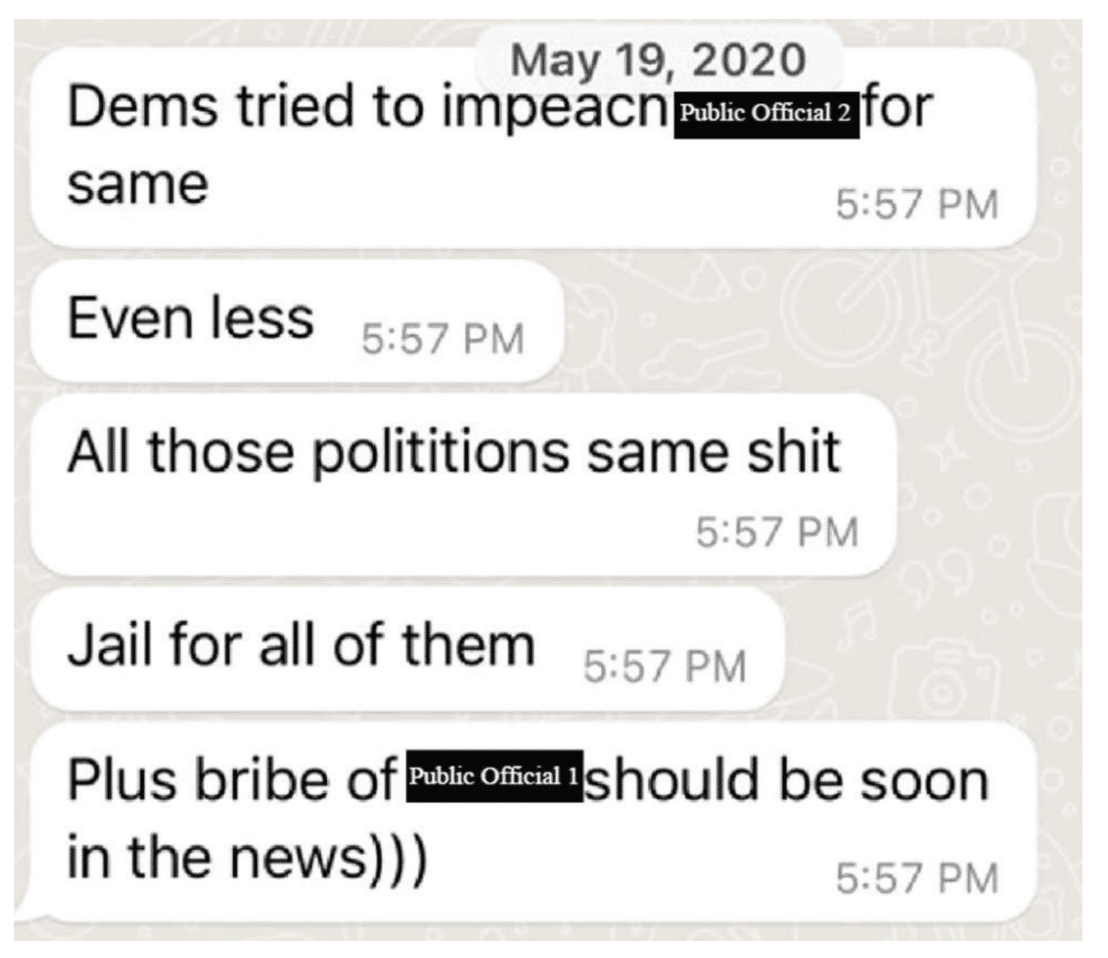

It has to do with Roger Stone.

In an effort to claim that Hunter Biden deserves to be criminally prosecuted for tax crimes when Roger Stone was permitted a civil settlement, David Weiss falsely claimed something distinguishes Hunter — that he wrote a memoir about his alleged crime and Stone did not — when in fact, the memoir Stone did reissue during the period he was defrauding the IRS was more closely connected to Stone’s other, more damaging crimes, than Hunter’s memoir was.

If a memoir justifies a tax indictment, then Stone, not Hunter, should be the one facing prison right now.

David Weiss waives response about the import of threats to his family

There are two ways the Los Angeles vindictive prosecution discussion in Weiss’ twin prosecutions of Hunter Biden differs from the one in Delaware, at least so far. Most obviously, it’s a tax case, not a gun case, so Hunter’s attorney Abbe Lowell is making a different argument about how unusual it is for DOJ to charge someone who, like Hunter, late filed his tax returns before he knew of a criminal investigation and then, later, paid those taxes, with penalties.

That’s one difference.

A more subtle one is that Lowell, in his motion to dismiss, made explicit something he had not before: at the time David Weiss reneged on a signed diversion and plea deal, the Special Counsel feared for the safety of his family.

As a result, Mr. Weiss reported he and others in his office faced death threats and feared for the “safety” of his team and family.22

In his response, Weiss didn’t acknowledge, at all, that his own fears for the safety of his family have been made a part of the official record.

Instead, he continued to claim there’s no logical explanation for how the pressure ginned up by Trump and Republicans in Congress led him to renege on a signed plea deal. Weiss continued to claim that any connection is fictional.

[T]o state an obvious fact that the defendant continues to ignore, former President Trump is not the President of the United States. The defendant fails to explain how President Biden or the Attorney General, to whom the Special Counsel reports, or the Special Counsel himself, or his team of prosecutors, are acting at the direction of former President Trump or Congressional Republicans, or how this current Executive Branch approved allegedly discriminatory charges against the President’s son at the direction of former President Trump and Congressional Republicans. The defendant’s fictious narrative cannot overcome these two inescapable facts.

[snip]

Second, to state the obvious, former President Trump is not the President. The defendant’s father is the President. The defendant fails to establish how President Biden or the Attorney General, to whom the Special Counsel reports, or the Special Counsel himself, or his team of prosecutors, are being improperly pressured by former President Trump or Congressional Republicans, such that the Executive Branch approved allegedly selective and vindictive charges to be brought against the President’s son in violation of the law. [my emphasis]

The centrality of Weiss’ claims that President Biden has a role in all this — leftover from the period when the Alexander Smirnov prong of the investigation remained secret — is all the more ridiculous now that it’s public that, after Weiss reneged on the plea deal, he chased Russian disinformation framing Joe Biden.

But is also utterly false that Lowell offered no explanation for how pressure from Trump led Weiss to renege on that plea deal. Once you include Weiss’ own stated fear for his family in the face of threats ginned up by Trump and Congress, what Weiss himself called intimidation, Lowell has established how pressure from Trump and Congress might have led Weiss to capitulate to that pressure. The fear of stochastic terrorism is all you need.

Which brings us to Roger Stone.

Abbe Lowell raises Roger Stone as a tax cheat who got a civil resolution

As noted, the Los Angeles indictment against Hunter is a tax case. And in a selective and vindictive prosecution claim, you need to explain the norm to be able to prove you’re being treated differently. To be sure, this filing is even less focused on selective prosecution, as opposed to vindictive prosecution, than the gun case, meaning such arguments are a small part of the argument. But Weiss has been unduly focused on selective prosecution from even before Hunter first made the claim, presumably because it’s easier to prove that the Hunter Biden case is different than anything DOJ has seen before than to rebut the evidence that Donald Trump and Bill Barr tried to frame Hunter and David Weiss is a witness to that effort.

So the selective prosecution argument, in which defendants have to argue that people just like them have not been charged before, was a minor part of this filing.

But it explains why Roger Stone ended up in a footnote of the filing — as Chris Clark promised they would do over a year ago.

56 The government does not generally bring criminal charges for failing to file or pay taxes, especially if the individual paid the taxes, interest, and penalty afterwards, as Mr. Biden did in October 2021. According to the IRS Data Book for 2021, 2,600,000 taxpayer returns were not timely filed. Many, if not the vast majority, of those cases were resolved with civil resolutions, even in the most high-profile cases. For example, in United States v. Shaughnessy, a DC law partner and his wife failed to file and pay their taxes for 11 years with nearly $7.2 million owed. DOJ ultimately resolved this civilly with tax, penalties and interest only. See Joint Motion for Entry of Consent Judgment, No. 22-cv-02811-CRC (D.D.C. 2023), DE 9. In United States v. Stone, where former Trump adviser Roger Stone and his wife owed nearly $2 million in unpaid taxes for 4 years, DOJ again resolved the matter civilly. No. 21-cv-60825-RAR (S.D. Fla. 2022), DE 64.

Here’s how Weiss, treating this as the guts of Lowell’s selective prosecution claim and therefore distracting from the rest of it, responded to that footnote:

The defendant compares himself to only two individuals: Robert Shaughnessy and Roger Stone, both of whom resolved their tax cases civilly for failing to pay taxes. Shaughnessy failed to file and pay his taxes, but he was not alleged to have committed tax evasion. By contrast, the defendant chose to file false returns years later, failed to pay when those returns were filed, and lied to his accountants repeatedly, claiming personal expenses as business expenses. Stone failed to pay his taxes but did timely file his returns, unlike the defendant. Neither Shaughnessy nor Stone illegally purchased a firearm and lied on background check paperwork. And neither of them wrote a memoir in which they made countless statements proving their crimes and drawing further attention to their criminal conduct. These two individuals are not suitable comparators, and since the defendant fails to identify anyone else, his claim fails. 5

Roger Stone’s tax fraud is different from Hunter Biden’s and that’s why Hunter’s selective and vindictive prosecution claim must fail, David Weiss says.

Weiss distinguishes Donald Trump’s rat-fucker from Joe Biden’s kid in three ways (note, Weiss doesn’t address that DOJ claimed Stone hid his business income, just as Hunter allegedly did):

- Stone didn’t pay his taxes, but did file timely returns

- Stone didn’t buy a gun while addicted (as far as we know — though there are pictures of Stone with guns and some of his associates have alleged that Stone had addiction problems in this period)

- Stone didn’t — Weiss claims — write a memoir “proving [his] crimes and drawing further attention to [his] criminal conduct”

It’s that last bullet that is garbage bullshit, sawdust-as-cocaine levels of stupid.

But let’s take them in order.

David Weiss uses gimmicks to limit extent that addiction can undermine the tax case

Regarding the first bullet, using the failure to file taxes in the LA case to distinguish Hunter from Stone is problematic for several reasons. First, Lowell is arguing that what changed between the plea agreement, which charged only failure to pay, and the tax indictment, which charged a mix of failure to file and failure to pay, was political pressure (and, now, threats that made Weiss worry about his family’s safety).

Notably, Weiss avoids claiming that Stone didn’t evade taxes, probably because the complaint against him alleges that Stone hid his income from the IRS in an alter ego, Drake Ventures, a kind of tax evasion for which Weiss has charged Hunter Biden, but for which Stone was not criminally charged. “By depositing and transferring” over $1 million paid to Stone in 2018 and 2019, “into the Drake Ventures’ accounts instead of their personal accounts, the Stones evaded and frustrated the IRS’s collection efforts,” the complaint alleges (my emphasis). Right there, in the complaint, DOJ claimed that Stone evaded IRS collection efforts, but Stone was not criminally charged.

To get to claiming that Hunter willfully failed to file his taxes charges during the years of his addiction, Weiss relies on a bunch of gimmicks that are at the core of his indictment against Hunter Biden. In Weiss’ responses to Lowell’s technical complaints about the indictment — which I wrote up here — he explained each of those technical complaints away using a gimmick designed to allow him to ratchet up the charges on Hunter while also mitigating the risk that Hunter’s addiction will make it harder to prove the tax case to a jury.

For example, in addition to claiming he could charge Hunter for the 2016 tax year because the President’s son signed tolling agreements with two entities — the Delaware US Attorney’s Office and DOJ Tax Division — that are not involved in this prosecution, Special Counsel Weiss claims that Hunter’s failure to pay his 2016 taxes occurred in 2020, when Hunter was sober, rather than 2016, when he misplaced a finalized tax submission.

Similarly, it’s not so much that Weiss charged Hunter twice for failing to pay his 2017 and 2018 taxes, which Lowell argued made the charges duplicitous, Weiss claims; it’s that Weiss intends to give the jury a choice for which year they want to convict Hunter on those charges — whether he failed to pay when he missed filing deadlines in 2018 and 2019 or he failed to do so when he ultimately filed in 2020, when he was sober.

It doesn’t matter that Hunter didn’t live in California for some of the tax years for which Weiss charged him in California, Weiss says, because Hunter lived in CA when he ultimately did file his taxes in 2020, without paying them. Weiss has used gimmick after gimmick to eliminate problems posed by both Hunter’s addiction and the fact that he filed his taxes before he learned of the criminal investigation into him, on top of the gimmick that he claims Hunter could afford to pay his tax burden in 2020 because Kevin Morris paid for some of his other expenses.

Effectively, to get around the willfulness problem posed by Hunter’s addiction, Weiss has shifted the date of Hunter’s crimes to 2020. But once you’ve done that, Hunter and Stone did the same thing: fail to pay taxes and also hide their income from 2018 (and 2019, in Stone’s case).

The gimmicks are just the kind of normal prosecutorial dickishness we’ve come accustomed to from this Baltimore crowd. But once you understand the effect of the gimmicks — to displace Hunter’s alleged crimes to 2020, when he submitted tax returns for four years at once — then Hunter and Stone are similarly situated, albeit with Stone accused of “evading” taxes in two calendar years, not one.

Weiss says a gun that was never fired is a worse related crime than witness tampering that was

But Weiss has a bigger problem with his effort to dismiss Stone as a comparator. He pulls two things out of his arse to present as distinguishers between Hunter Biden and Stone without (apparently) first doing the least little due diligence to check whether those things he pulled out of his arse have any basis in reality, much less to make sure they don’t actually prove him wrong.

David Weiss says that Hunter Biden is different from Roger Stone because he unlawfully owned a gun for 11 days in 2018. But the gun charge has no tie to the tax charge. Not even Weiss makes that claim!

Indeed, it’s the reverse: investigators decided not to charge gun crimes in 2018, before the tax investigation started. Prosecutors only reconsidered that because of the tax investigation — and (Lowell has alleged with no response from Weiss) because Republican politicians made Weiss afraid for the safety of his family. The only tie between the gun charges and the tax charges would be exculpatory in the tax case — Hunter’s addiction. Weiss’ prosecutors admitted the inverse relationship in Hunter’s initial appearance in Los Angeles. ‘[A]rguably,” Leo Wise said to Judge Mark Scarsi on January 11, “information in that case that is inculpatory in this case, may be arguably, exculpatory in that case.” The things prosecutors will use to prove Hunter was an addict in 2018 undermine prosecutors’ case that Hunter’s failure to file tax returns for 2017 and 2018 was willful.

By contrast, the government did claim that Roger Stone’s tax avoidance tied directly to his other crimes, crimes for which a jury had already found him guilty when DOJ filed the tax complaint in 2021.

The complaint against Stone described how he engaged in fraud to shelter his money because he was indicted.

40. In May 2017, the Stones entered into an installment agreement with the IRS that required them to pay $19,485 each month toward their unpaid taxes. They made these payments each month from a Drake Ventures’ Wells Fargo account.

41. Roger Stone was indicted on January 24, 2019, and the indictment was unsealed on January 25, 2019.

42. After Roger Stone’s indictment, the Stones created the Bertran Trust and used funds that they owned via their alter ego, Drake Ventures, to purchase the Stone Residence in the name of the Bertran Trust.

[snip]

52. The Stones intended to defraud the United States by maintaining their assets in Drake Ventures’ accounts, which they completely controlled, and using these assets to purchase the Stone Residence in the name of the Bertran Trust.

53. The Stones’ purchase of the Stone Residence using funds they held in the Drake Ventures’ Wells Fargo account is marked by numerous badges of fraud. They include:

a. The Stones were in substantial debt to the United States at the time of the transfer, rendering them insolvent at the time of the transfer and unable to pay their debt to the United States;

b. The Stones faced the threat of litigation. Roger Stone had just been indicted;

c. The Stones anticipated that the United States would resort to enforced collection of their unpaid tax liabilities once they defaulted on their monthly installment payments to the IRS; [my emphasis]

It seems DOJ believed that Stone sought to shelter his wealth in a Florida residence that would be beyond the reach of any criminal forfeiture, just like his buddy Paul Manafort did.

And this is why it matters that David Weiss continues to bury his confession to Congress that, when he reneged on the plea deal, he was afraid for the safety of his family.

The crimes for which Stone was indicted — the prosecution which DOJ explicitly tied to Roger Stone’s efforts to defraud the government — involved real threats, not the hypothetical threat of an addict owning a gun.

Roger Stone was convicted for trying to intimidate Randy Credico against testifying to Congress and Robert Mueller. Credico has described that his first contact with the FBI in 2018 was actually a Duty to Warn meeting associated with the plotting of Stone’s militia buddies, not a witness interview.

And Judge Amy Berman Jackson applied a sentencing enhancement for the threat Stone — again, with his militia buddies — made against her personally.

The defendant engaged in threatening and intimidating conduct towards the Court, and later, participants in the National Security and Office of Special Counsel investigations that could and did impede the administration of justice.

Before the Proud Boys launched an attack on the Capitol to prevent the peaceful transfer of power, before Stone allegedly threatened to assassinate one or another Democratic Congressman as well as Leo Wise and Derek Hines’ colleague and Stone prosecutor, Aaron Zelinsky, Enrique Tarrio helped Stone threaten his judge.

That’s the weapon Roger Stone was found guilty of wielding: stochastic terrorism that posed a risk to justice. Just like Donald Trump attacked David Weiss before Weiss got threats that led him to worry about the safety of his family.

And yet, having systematically ignored the threats that Donald Trump and other Republicans ginned up against his family, David Weiss is arguing that Hunter Biden owning a gun unrelated to failing to pay taxes is more incriminating than DOJ’s claims in the tax complaint that Stone’s adjudged witness intimidation tied directly to Stone’s efforts to defraud the IRS.

One is connected to the charged crime. One is not. One led to threats against a key witness and a judge. One did not.

But David Weiss, still refusing to acknowledge his testimony that he feared for the safety of his family, claims the one unconnected to the alleged tax crimes explains his decision to charge the tax crimes. Weiss’ claims about Stone don’t help his case, they show that a criminal case against Stone had more merit than this one.

David Weiss claims Hunter’s memoir is great evidence and then proves it is not

Crazier still, David Weiss is claiming that Hunter Biden wrote a memoir “proving [his] crimes and drawing further attention to [his] criminal conduct” of being an addict (neither the gun for which he is charged nor his failure to pay his taxes appear in the memoir) but Roger Stone did not.

To raise the stakes of this (embarrassingly false) claim, Weiss dedicates three paragraphs laying out how Hunter’s memoir helps to prove the gun case that, prosecutors have admitted, is inversely related to the tax case.

Then, after announcing his awareness of a federal investigation in late 2020, the following year (2021) he chose to author, sell, and promote his memoir, Beautiful Things, and to release an audiobook in a lucrative deal that heightened his prominence and drew further attention to his crimes. 1

1 As outlined in the Indictment, the defendant made statements and admissions in the book relevant to the charges against him.

B. The Defendant Also Chose to Commit Serious Gun Crimes

The defendant’s crimes were not limited to tax violations. In 2018, he chose to purchase a gun, he chose to lie on background check paperwork by stating he was not addicted to drugs, and he certified that his answers on the paperwork were true, when in fact, he had lied about his addiction. See generally United States v. Robert Hunter Biden, Indictment, Dkt. 40 (D. Del). When he later chose to publish his memoir, he included countless admissions about his drug use in 2018 when he possessed the gun.

Again, prosecutors have described that these cases are inversely related. If you prove that Hunter was an addict, as Weiss says the memoir helps him do, you also make it harder to prove that the failure to file for 2017 and 2018 was willful.

Here’s how Weiss treats Hunter’s memoir in the equivalent filing in the gun crimes case.

After the defendant publicly announced his awareness of a federal investigation of him in late 2020, see ECF 63 at 5, the following year (2021) he chose to author, sell and promote his memoir, Beautiful Things, and to release an audiobook in a lucrative book deal. Relevant to the charges in this matter, the defendant made expansive admissions about his extensive and persistent drug use, including throughout the year 2018 when he purchased the gun. For example, the defendant admitted that he was experiencing “full blown addiction” to crack cocaine and by the fall of 2018 he had gotten to the point that:

It was me and a crack pipe in a Super 8, not knowing which the fuck way was up. All my energy revolved around smoking drugs and making arrangements to buy drugs—feeding the beast. To facilitate it, I resurrected the same sleep schedule I’d kept in L.A.: never. There was hardly any mistaking me now for a so-called respectable citizen. Crack is a great leveler.

Hunter Biden, Beautiful Things (2021) at 203, 208

In the Delaware case, Weiss is arguing something different than he is in the LA case, that is about how much evidence (Weiss claims) there is to prove the gun case. As I noted, that’s actually counterproductive in the selective prosecution response, because it proves that the evidence Weiss claims to think is so damning was available in 2021, before he decided to divert the gun crime in 2023, before he came to fear for the safety of his family and then reneged on that diversion agreement.

Oh. And also? Weiss again botches the evidence. The passage cited above about a crack pipe in a Super 8 on page 208 describes the aftermath, in February 2019, of the Ketamine treatment Hunter got from Roger Stone buddy Keith Ablow that — Hunter’s memoir describes — made things worse.

The therapy’s results were disastrous. I was in no way ready to process the feelings it unloosed or prompted by reliving past physical and emotional traumas. So I backslid. I did exactly what I’d come to Massachusetts to stop doing. I’d stay clean for a week, break away from the center to meet a connection I found in Rhode Island, smoke up, then return.

[snip]

Finally, the therapist in Newburyport said there was little point in our continuing.

“Hunter,” he told me, with all the exasperated, empathetic sincerity he could muster, “this is not working.”

I headed back toward Delaware, in no shape to face anyone or anything. To ensure that I wouldn’t have to do either, I took an exit at New Haven. For the next three or four weeks, I lived in a series of low-budget, low-expectations motels up and down Interstate 95, between New Haven and Bridgeport.

I exchanged L.A.’s $400-a-night bungalows and their endless parade of blingy degenerates for the underbelly of Connecticut’s $59-a-night motel rooms and the dealers, hookers, and hard-core addicts—like me—who favored them. I no longer had one foot in polite society and one foot out. I avoided polite society altogether. I hardly went anywhere now, except to buy. It was me and a crack pipe in a Super 8, not knowing which the fuck way was up. [my emphasis]

This is in no way a description of the state of Hunter’s addiction in “fall of 2018,” when he bought a gun. It’s a description of the state of Hunter’s addiction in February 2019, after treatment from Ablow exacerbated the addiction. To make things worse, Hunter gets the timing of the 2019 follow-up treatment wrong in the book, saying it happened in February when it started in January. This passage is utterly worthless to prove the gun crime, and instead helps to prove that memoirs, especially those written by recovering addicts, are prone to narrative embellishment and error.

To sum up how dumb it is to use the memoir to rebut a selective prosecution claim at all: First, the existence of a 2021 memoir doesn’t help Weiss’ selective prosecution rebuttal in either case, because that evidence was available before Weiss decided to resolve both cases without jail time in June 2023 and so only raises more questions about why he reneged on that deal. The memoir actually isn’t all that helpful to prove the status of Hunter’s addiction in October 2018, because Hunter doesn’t provide as much detail of that as he did of his exploits in Los Angeles, from earlier in the year. Worse still, relying on a passage describing events in February 2019, after Ketamine treatment led Hunter to backslide, and claiming it describes the status of Hunter’s addiction in fall 2018 is only going to prove you never bothered to check your evidence before you indicted on gun crimes. And, finally, Weiss’ prosecutors have admitted there’s an inverse relationship between these two cases! Proving that Hunter was addicted in this period will only make it harder to prove that his non-payment in 2017 and 2018 was willful and may even provide basis to argue that Hunter didn’t willfully lie to his accountant in 2020, but rather couldn’t remember what happened in 2018. The fact that Hunter gets dates wrong in the memoir will actually help that case.

It’s all such a nutty argument, using this memoir as a distinguisher in the tax case.

Roger Stone’s memoir was far more closely connected to his crimes and tax evasion than Hunter’s was

Nuttier still, given the fact — fact! — that Roger Stone did too write a memoir about his crimes!

The claim that Stone didn’t write a memoir about his crimes is as transparently, embarrassingly false as David Weiss’ claim that a photo of a photo of sawdust was instead a picture of Hunter Biden’s cocaine.

Not only did Stone write a memoir about his claimed actions in the 2016 election, he reissued it in paperback, with a lengthy introduction in which he codified the cover story that would prove to be false at trial later that year. As noted in this post, that introduction made a number of claims that were part of Stone’s cover story, including:

- Describes learning he was under investigation on January 20, 2017

- Discounts his May 2016 interactions with “Henry Greenberg” — a Russian offering dirt on Hillary Clinton — by claiming Greenberg was acting as an FBI informant

- Attributes any foreknowledge of WikiLeaks’ release to Randy Credico and not Jerome Corsi or their yet unidentified far more damning source while disclaiming any real foreknowledge

- Gives Manafort pollster, Tony Fabrizio, credit for the decision to focus on Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania in the last days of the election

- Blames Jeff Sessions for recusing from the Russian investigation

- Harps on the Steele dossier

- Dubiously claims that in January 2017, he didn’t know how central Mueller’s focus would be on him

- Suggests any charges would be illegitimate

- Complains about his financial plight

- Falsely claims the many stories about his associates’ testimony comes from Mueller and not he himself

- Repeats his Randy Credico cover story and discounts his lies to HPSCI by claiming his lawyers only found his texts to Credico after the fact

- Suggests Hillary had ties to Russia

- Notes that Trump became a subject of the investigation after he fired Jim Comey [my emphasis]

Those two bolded bits are the core of the case that would be charged in January 2019 and convicted in November 2019. This introduction is part of the same cover-up, one that attempts to profit off his cover-up and protection of Donald Trump.

He reissued it, in part, for financial reasons, including an effort to pay collaborators in the 2016 story that were likely also trial witnesses. That paperback came out in precisely the period in 2019 during which, the tax claim against Stone alleged, he was shifting money to defraud the government because he had been indicted. Stone planned a media blitz that clashed with the gag imposed on him — imposed on him, again, because he and his militia buddies were posting pictures of Judge ABJ with a crosshairs on it.

We know all this because Roger Stone almost went to jail for it. This post describes that conflict.

On February 21, 2019, Amy Berman Jackson gagged Stone in response to the Instagram post targeting her, describing that his incitement might lead “others with extreme views and violent inclinations” to take action.

Let me be clear, at the time of his post he was permitted to criticize the special counsel, the designation of the cases related, and the previous decisions of the judge to whom the case had been assigned. But I am not reassured by the defense suggestion that Mr. Stone is just all talk and no action and this was just a big mistake.

What concerns me is the fact that he chose to use his public platform, and chose to express himself in a manner that can incite others who may feel less constrained. The approach he chose posed a very real risk that others with extreme views and violent inclinations would be inflamed. You don’t have to read the paper beyond today to know that that’s a possibility.

And these were, let there be no mistake, deliberate choices. I do not find any of the evolving and contradictory explanations credible. Mr. Stone could not even keep his story straight on the stand, much less from one day to another. There is some inconsistency in his telling me on the one hand that these public communications are an existential endeavor, essential not only to his income but his very identity, and then, on the other hand, telling us, It wasn’t me.

On March 1, Stone’s attorneys filed a “notice” arguing that the book should not be covered by her gag. On March 4, they submitted a filing saying, oops! it is too late. On March 5, ABJ denied Stone’s request that the book be excluded from the gag and ordered more briefing. On March 11, Stone submitted a bunch of documentation showing (among other things) that at least one of his attorneys was centrally involved in the book publication.

The Bertran Trust was not only an effort to keep money away from the IRS.

It was an attempt to keep the proceeds of a book that violated the gag order imposed to avoid more incitement. It was an attempt to profit off continuing to protect Donald Trump.

And David Weiss, after relying on a Hunter Biden memoir that might help prove the gun case but actually hurts his tax case, claims that memoir doesn’t exist.

And that’s before you consider the book introduction that Stone wrote for Keith Ablow, the guy whose therapy — Hunter’s memoir describes — made his addiction worse, the guy in whose cottage Hunter was staying when his life was packaged up to be sent to David Weiss to use in prosecution.

After looking at Keith Ablow’s sawdust picture and claiming it was Hunter’s cocaine, Weiss has now looked at Ablow buddy Roger Stone and claimed that a memoir that is more closely connected with his tax dodging and dangerous crimes and instead claimed that memoir simply doesn’t exist.

And that is the basis Weiss gives for charging Hunter Biden with tax crimes.

Timeline

October 30, 2018: ABC reports that Stone hired Bruce Rogow in September, a First Amendment specialist who has done extensive work with Trump Organization.

October 31, 2018: Date Corsi stops making any pretense of cooperating with Mueller inquiry.

November 6, 2018: Democrats win the House in mid-term elections.

November 7, 2018: Trump fires Jeff Sessions, appoints Big Dick Toilet Salesman Matt Whitaker Acting Attorney General.

November 8, 2018: Prosecutors first tell Manafort they’ll find he breached plea deal.

November 12, 2018: Date Corsi starts blowing up his “cooperation” publicly.

November 14, 2018: Date of plea deal offered by Mueller to Corsi.

November 15, 2018: Mike Campbell pitches Stone on a paperback — in part to ‘retake the narrative — including a draft of the new introduction.

November 18, 2018: Jerome Corsi writes up his cover story for how he figured out John Podesta’s emails would be released.

November 20, 2018: After much equivocation, Trump finally turns in his written responses to Mueller.

November 21, 2018: Dean Notte reaches out to Grant Smith suggesting a resolution to all the back and forth on their joint venture, settling the past relationship in conjunction with a new paperback.

November 22, 2018: Corsi writes up collapse of his claim to cooperate.

November 23, 2018: Date Mueller offers Corsi a plea deal.

November 26, 2018: Jerome Corsi publicly rejects plea deal from Mueller and leaks the draft statement of offense providing new details on his communications with Stone.

November 26, 2018: Mueller deems Paul Manafort to be in breach of his plea agreement because he lied to the FBI and prosecutors while ostensibly cooperating.

November 27, 2018: Initial reports on contents of Jerome Corsi’s book, including allegations that Stone delayed release of John Podesta emails to blunt the impact of the Access Hollywood video.

November 29, 2018: Michael Cohen pleads guilty in Mueller related cooperation deal.

December 2, 2018: Roger Stone claims in ABC appearance he’d never testify against Trump and that he has not asked for a pardon.

December 3, 2018: Trump hails Stone’s promise not to cooperate against him.

December 9, 2018: Stone replies to Campbell saying that because he never made money on Making of the President, he has no interest.

December 13, 2018: Tony Lyons and Grant Smith negotiate a deal under which Sky Horse would buy Stone out of his hardcover deal with short turnaround, then expect to finalize a paperbook by mid January. This is how Stone gets removed from the joint venture — in an effort to minimize his risk.

December 14, 2018: Mueller formally requests Roger Stone’s transcript from House Intelligence Committee.

December 17, 2018: Smith, saying he and Stone have discussed the deal at length, sends back a proposal for how it could work. This is where he asks for payment the next day, to pay someone off for work on the original book.

For some reason, in the ensuing back-and-forth, Smith presses to delay decision on the title until January.

December 19, 2018: It takes two days to get an agreement signed and Stone’s payment wired.

December 20, 2018: HPSCI votes to release Stone’s transcript to Mueller.

January 1, 2019: Stone includes Keith Ablow on his annual best dressed list.

January 8, 2019: Paul Manafort’s redaction fail alerts co-conspirators that Mueller knows he shared polling data with Konstantin Kilimnik.

January 13, 2019: Stone drafts new introduction, which he notes is “substantially longer and better than the draft sent to me by your folks.” He asks about the title again.

January 14, 2019: Stone sends the draft to Smith and Lyons. It is 3386 words long. Lyons responds, suggesting as title, “The Myth of Collusion; The Inside Story of How I REALLY Helped Trump Win.” Lyons also notes Stone can share the book with Senators.

Stone responds suggesting that he could live with, “The Myth of Collusion; The Inside Story of How Donald Trump really won,” noting, “I really can’t be seen taking credit for HIS victory.”

By end of day, Skyhorse’s Mike Campbell responds with his edits.

January 15, 2019: The next morning, Smith responds with his edits, reminding that Stone has to give final approval. Stone does so before lunch. Skyhorse moves to working on the cover. Late that day Campbell sends book jacket copy emphasizing Mueller’s “witch hunt.”

January 16, 2019: Tony Lyons starts planning for the promotional tour, asking Stone whether he can be in NYC for a March 5 release. They email back and forth about which cover to use.

January 18, 2019: By end of day Friday, Skyhorse is wiring Stone payment for the new introduction.

January 24, 2019: Mike Campbell tells Stone the paperback “is printing soon,” and asks what address he should send Stone’s copies to. WaPo reports that Mueller is investigating whether Jerome Corsi’s “severance payments” from InfoWars were an effort to have him sustain Stone’s story. It also reports that Corsi’s stepson, Andrew Stettner, appeared before the grand jury. That same day, the grand jury indicts Stone, but not Corsi.

January 25, 2019, 6:00 AM: Arrest of Roger Stone.

January 25, 2019, 2:10 PM: Starting the afternoon after Stone got arrested, Tony Lyons starts working with Smith on some limited post-arrest publicity. He says Hannity is interested in having Stone Monday, January 28 “Will he do it?” Smith replies hours later on the same day his client was arrested warning, “I need to talk to them before.”

January 26, 2019: Lyons asks Smith if Stone is willing to do a CNN appearance Monday morning, teasing, “I guess he could put them on the spot about how they really go to this house with the FBI.”

January 27, 2019: Smith responds to the CNN invitation, “Roger is fully booked.” When Lyons asks for a list of those “fully booked” bookings, Smith only refers to the Hannity appearance on the 28th, and notes that Kristin Davis is handling the schedule. Davis notes he’s also doing Laura Ingraham.

January 28, 2019: The Stones pay $19,485 to IRS.

January 28, 2019: The plans for Hannity continue on Monday, with Smith again asking for the Hannity folks to speak to him “to confirm the details.” In that thread, Davis and Lyons talk about how amazing it would be to support “another New York Times Bestseller” for Stone.

February 15, 2019: After two weeks — during which Stone was indicted, made several appearances before judges, and had his attorneys submit their first argument against a gag — Stone responded to Campbell’s January 24 email providing his address, and then asking “what is the plan for launch?” (a topic which had already been broached with Lyons on January 16). Campbell describes the 300-400 media outlets who got a review copy, then describes the 8 journalists who expressed an interest in it. Stone warns Campbell, “recognize that the judge may issue a gag order any day now” and admits “I also have to be wary of media outlets I want to interview me but don’t really want to talk about the book.”

February 18, 2019: Release of ebook version of Stone’s reissued book.

February 21, 2019: After Stone released an Instagram post implicitly threatening her, Amy Berman Jackson imposes a gag on Stone based on public safety considerations.

February 25, 2019: The Stones transfer $70,000 from Drake to Attorney account.

February 28, 2019: The Stones transfer $70,000 from Drake to Attorney account. The Stones pay $19,485 to IRS.

March 1, 2019: Ostensible official release date of paperback of Stone’s book. Stone submits “clarification” claiming that the book publication does not violate the gag.

March 4, 2019: Stone submits filing saying it is too late to hold the book.

March 5, 2019: The Stones establish Bertran Trust.

March 5, 2019: ABJ denies Stone’s request to exclude the book from the gag and orders further briefing.

March 11, 2019: Stone response to ABJ order, including exhibits showing that at least one of his attorneys knew of the imminent book release at the gag hearing.

March 22, 2019: The Stones purchase condo using $140,000 transfered from Drake Ventures account.

March 27, 2019: The Certificate of Trust recorded in Broward.

March 28, 2019: The Stones fail to make IRS payment, leading to default.

May 24, 2019: The Stones open three bank accounts in name of Bertran Trust.

June 2, 2020: Roger Stone writes forward to Keith Ablow book celebrating Trump.