The Espionage Act Evidence WaPo Spins as Obstruction Evidence

The WaPo, with Devlin Barrett as lead byline and Mar-a-Lago Trump-whisperer Josh Dawsey next, has a report describing either new evidence or more evidence of obstruction in the stolen documents case.

Some of it, such as that investigators “now suspect that boxes including classified material were moved from Mar-a-Lago storage area after the subpoena was served,” is not new — not to investigators and not to the public. The version of the search affidavit released on September 14 showed that on June 24 investigators subpoenaed the surveillance footage for the storage room and at least one other, still-redacted location, going back to January 10, 2022, long before subpoena for documents with classification marks was served on May 11. So unless Trump withheld surveillance footage, then DOJ has known since early July 2022 on what specific dates boxes were moved. And a redacted part of the affidavit explains the probable cause the FBI had in August that there might be classified documents in Trump’s residential suite.

In other words, much of what WaPo describes is that DOJ has obtained substantial evidence since August to prove the probable cause suspicions already laid out in their August warrant affidavit. You don’t search the former President’s beach resort without awfully good probable cause, and they were able to show substantial reason to believe that Trump had boxes moved to his residence after he received the May 11 subpoena, where he sorted out some he wanted to keep, eight months ago.

They’ve just gotten a whole lot more proof that they were right, since.

Other parts of the story do describe previously unknown (to us, at least) details, and those may be significantly more important for Trump’s fate. The most intriguing, to me, is that witnesses are being asked about Trump’s obsession with Mark Milley.

Investigators have also asked witnesses if Trump showed a particular interest in material relating to Gen. Mark A. Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, people familiar with those interviews said. Milley was appointed by Trump but drew scorn and criticism from Trump and his supporters after a series of revelations in books about Milley’s efforts to rein in Trump toward the end of his term. In 2021, Trump repeatedly complained publicly about Milley, calling him an “idiot.”

The people did not say whether investigators specified what material related to Milley they were focused on. The Post could not determine what has led prosecutors to press some witnesses on those specific points or how relevant they may be to the overall picture that Smith’s team is trying to build of Trump’s actions and intent.

Remember that reports on investigations, especially ones that include Mar-a-Lago court reporters, often amount to witnesses attempting to share questions they’ve been asked with other witnesses or lawyers. Trump’s team has no idea what kinds of classified items were seized. This detail suggests that among the classified documents seized are a document or documents pertaining to Milley.

According to Bobs Woodward and Costa in Peril, Milley called China twice in the last months of the Trump administration to reassure his counterpart that the US was not going to attack China without some build-up first.

On Friday, October 30, four days before the election, Chairman Milley examined the latest sensitive intelligence. What he read was alarming: The Chinese believed the United States was going to attack them.

Milley knew it was untrue. But the Chinese were on high alert, and whenever a superpower is on high alert, the risk of war escalates. Asian media reports were filled with rumors and talk of tensions between the two countries over the Freedom of Navigation exercises in the South China Sea, where the U.S. Navy routinely sails ships in areas to challenge maritime claims by the Chinese and promote freedom of the seas.

There were suggestions that Trump might want to manufacture a “Wag the Dog” war before the election so he could rally the voters and beat Biden.

[snip]

This was such a moment. While he often put a hold on or stopped various tactical and routine U.S. military exercises that could look provocative to the other side or be misinterpreted, this was not a time for just a hold. He arranged a call with General Li.

Trump was attacking China on the campaign trail at every turn, blaming them for the coronavirus. “I beat this crazy, horrible China virus,” he told Fox News on October 11. Milley knew the Chinese might not know where the politics ended and possible action began.

To give the call with Li a more routine flavor, Milley first raised mundane issues like the staff-to-staff communications and methods for making sure they could always rapidly reach each other.

Finally, getting to the point, Milley said, “General Li, I want to assure you that the American government is stable and everything is going to be okay. We are not going to attack or conduct any kinetic operations against you.

“General Li, you and I have known each other for now five years. If we’re going to attack, I’m going to call you ahead of time. It’s not going to be a surprise. It’s not going to be a bolt out of the blue.

The two Bobs also described how, in the days after January 6, Milley reviewed nuclear launch procedures with senior officers of the National Mission Command Center to make sure he would be in the loop if Trump ordered the use of nukes.

Without providing a reason, Milley said he wanted to go over the procedures and process for launching nuclear weapons.

Only the president could give the order, he said. But then he made clear that he, the chairman of the JCS, must be directly involved. Under current procedure, there was supposed to be a voice conference call on a secure network that would include the secretary of defense, the JCS chairman and lawyers.

“If you get calls,” Milley said, “no matter who they’re from, there’s a process here, there’s a procedure. No matter what you’re told, you do the procedure. You do the process. And I’m part of that procedure. You’ve got to make sure that the right people are on the net.”

If there was any doubt what he was emphasizing, he added, “You just make sure that I’m on this net. “Don’t forget. Just don’t forget.”

He said that his statements applied to any order for military action, not just the use of nuclear weapons. He had to be in the loop.

Since these details about Milley came out, Trump and his frothers have claimed Milley committed treason, in concert with Nancy Pelosi (who had expressed concerns to Milley about the safety of America’s nuclear arsenal).

The attack on Milley is the same kind of manufactured grievance — often cultivated by investigation witness Kash Patel (who was DOD Chief of Staff during the transition) — as the Russian investigation. That other inflated grievance led Trump to compile a dumbass binder of sensitive documents that didn’t substantiate his grievances. If Trump did the same with Milley, either before or after he left office, those documents might include highly sensitive documents, including SIGINT reports about China’s response to Milley’s contacts.

If DOJ were ever to charge Trump for refusing to give back classified documents under 18 USC 793(e), DOJ would select a subset of the documents to charge, probably from among those seized in August. They would pick those that, if declassified for trial, would not do new damage to national security, documents that would allow prosecutors to tell a compelling story at trial. And given WaPo’s report, there’s good reason to think there’s a story they think they could tell about documents that may be part of Trump’s grievance campaign against Milley.

WaPo also described that witnesses are being asked whether Trump shared documents, including a map, with donors.

As investigators piece together what happened in May and June of last year, they have been asking witnesses if Trump showed classified documents, including maps, to political donors, people familiar with those conversations said.

According to the story, communications from Trump’s former Executive Assistant, Molly Michael, have been key for investigators.

[A]uthorities have another category of evidence that they consider particularly helpful as they reconstruct events from last spring: emails and texts of Molly Michael, an assistant to the former president who followed him from the White House to Florida before she eventually left that job last year. Michael’s written communications have provided investigators with a detailed understanding of the day-to-day activity at Mar-a-Lago at critical moments, these people said.

Michael is likely the person in whose desk drawer at least two of the classified documents seized in August were found: the two “compiled” with messages from a pollster, a faith leader, and a book author, the kind of document you would show to donors. That document, which combines two classified documents obtained before Trump left the White House with messages from after he left, is the kind of smoking gun that shows Trump didn’t just hoard documents because of ego (as Barrett reported even after the existence of this document was made public), but because he was putting classified documents to his own personal use. We learned back in November that there was evidence that Trump had used two classified documents in what sounds like a campaign document. Perhaps one of those classified documents was a map (of Israel? of Ukraine?).

Whatever it is, this is the kind of story prosecutors might like to tell at stolen classified document trials, not just because it would show Trump putting the nation’s secrets to his own personal gain and sharing classified documents with people who never had clearance, but because it would be proof that people on Trump’s team knew of and accessed documents after they lost their need to access such documents. This document would go a long way to proving that Trump didn’t just hoard classified documents out of negligence (which is currently the explanation why both Joe Biden and Mike Pence did), but because he wanted to make use of what he took.

Molly Michael is also the person who ordered a more junior aide to make a digital copy of Trump’s schedules from when he was President, an order that led to documents with classification markings being loaded to a laptop and likely to the cloud. That’s another example of the kind of exploitation of classified documents that would make a good story at trial.

It’s also the kind of story that could expose Michael herself to Espionage Act charges, such that she might work hard to minimize her own exposure. And yes, because she was Trump’s Executive Assistant, both at the White House and after he moved back to Mar-a-Lago, she likely can explain a lot about how Trump used documents he took from the White House and brought to Mar-a-Lago, including documents used as part of his political campaigning afterwards.

Without conceding it was incorrect, WaPo notes that in November, after it was already public that Trump had self-interested reason to refuse to return documents, it reported it was all just ego (it now attributes that conclusion entirely to what Trump told his aides, not — as claimed in the first line of last fall’s story — what “Federal agents and prosecutors have come to believe”).

Such alleged conduct could demonstrate Trump’s habits when it came to classified documents, and what may have motivated him to want to keep the papers. The Post has previously reported that Trump told aides he did not want to return documents and other items from his presidency — which by law are supposed to remain in government custody — because he believed they belonged to him.

Even in a story describing prosecutors collecting evidence about at least two stories about classified records that they might tell at a trial, the WaPo remarkably suggests to readers that obstruction is the primary crime being investigated here.

The application for court approval for that search said agents were pursuing evidence of violations of statutes including 18 USC 1519, which makes it a crime to alter, destroy, mutilate or conceal a document or tangible object “with the intent to impede, obstruct, or influence the investigation or proper administration of any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency.”

A key element in most obstruction cases is intent, because to bring such a charge, prosecutors have to be able to show that whatever actions were taken were done to try to hinder or block an investigation. In the Trump case, prosecutors and federal agents are trying to gather any evidence pointing to the motivation for Trump’s actions.

[snip]

Investigators have also amassed evidence indicating that Trump told others to mislead government officials in early 2022, before the subpoena, when the National Archives and Records Administration was working with the Justice Department to try to recover a wide range of papers, many of them not classified, from Trump’s time as president, the people familiar with the investigation said. While such alleged conduct may not constitute a crime, it could serve as evidence of the former president’s intent.

By treating this as only an obstruction investigation, WaPo incorrectly claims that lying to NARA (as opposed to the FBI) could not be part of a crime.

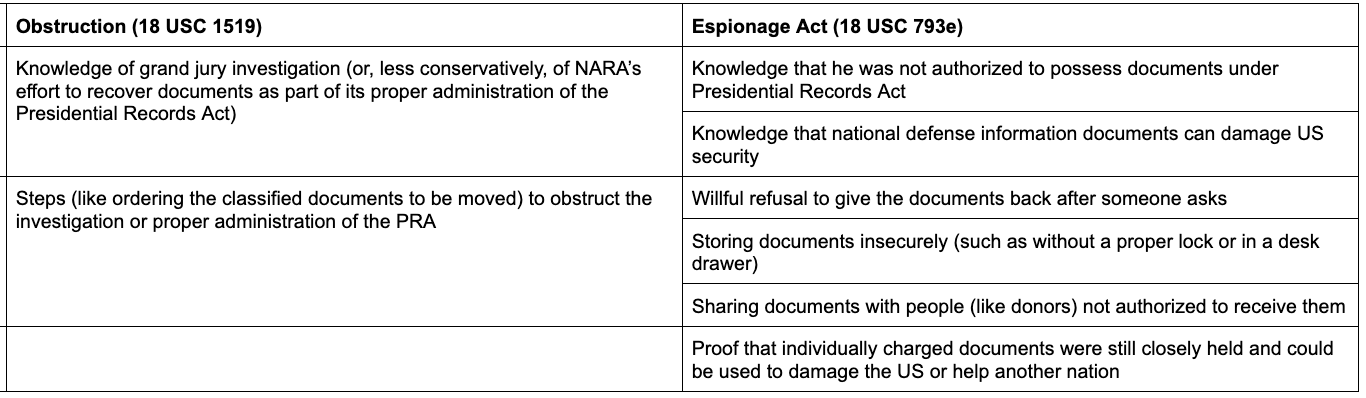

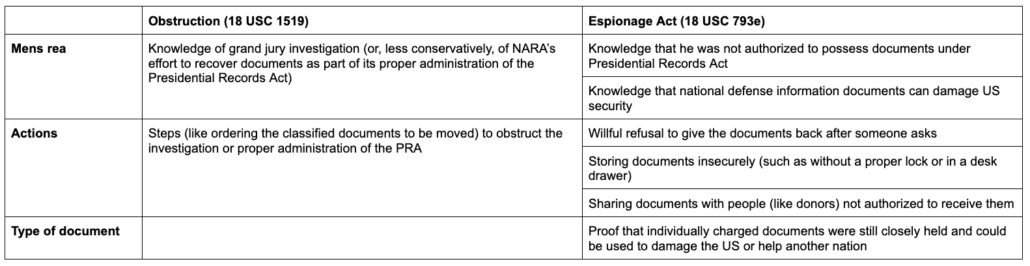

Here’s my attempt to lay out the elements of offense of both crimes — what prosecutors would have to prove at trial (I wrote more about the elements of an 18 USC 793e charge here and here).

To prove obstruction, DOJ would focus on the things of which — WaPo describes — Jack Smith’s team has developed substantial proof. Most conservatively, they would pertain to a grand jury investigation, because that application would be uncontroversial. After DOJ sent Trump a grand jury subpoena (which would be presented at trial as proof that Trump had notice of the grand jury investigation, his knowledge of which Evan Corcoran’s recent testimony would further corroborate), Trump took steps to hide documents and thereby prevent full compliance with that subpoena, and so thwarted a grand jury investigation. That’s your obstruction charge.

DOJ could charge a second act of obstruction tied to NARA’s effort to recover documents as part of its proper administration of the Presidential Records Act. But such an application would be guaranteed to be appealed. So the safer route would be to charge behavior that post-dates Trump’s knowledge of the grand jury investigation (and indeed, WaPo describes a close focus on events that took place starting last May).

But Trump’s longer effort to deceive the government in order to hoard documents is proof of 18 USC 793(e). To prove that, DOJ would need to prove that the government, whether NARA or FBI, told Trump he was not authorized to have documents covered by the Presidential Records Act, a subset of which would include documents with classification marks. They would need to show that Trump had been told about why he needed to protect classified records, which Trump’s former White House counsels and Staff Secretary have described (and documented) doing. For good measure they would show that Jay Bratt affirmatively told Trump that he had been (and, the August search would prove, was still) storing classified documents in places not authorized for such storage.

To prove 18 USC 793(e) at trial, you would need to describe specific documents Trump refused to give back and explain to a jury why they fit the definition of National Defense Information, material that remained closely held that, if released, could do damage to the US. That may be why they’re asking questions about Trump’s obsession with Milley or sharing maps with donors: because it’s part of the story that prosecutors would tell at trial, if they were to charge 18 USC 793.

All of which is to say that WaPo not only reported that DOJ has collected more evidence to prove what DOJ already suspected when they did the search on August 8, but they’ve been collecting information that would go beyond that, to a hypothetical Espionage Act charge.

Charging a former President with violating the Espionage Act is still an awfully big lift, and in the same way that charging obstruction for impeding NARA’s proper administration of the Presidential Records Act would invite an appeal, charging 18 USC 793(e) in DC would invite a challenge on venue (and charging it in Florida would risk spending the next three years fighting Aileen Cannon). But in addition to developing more evidence to prove the suspicions that they already substantiated in August, WaPo describes Jack Smith’s team asking the kinds of questions — about specific documents that might be charged as individual violations of the Espionage Act — that you’d ask before charging it.

Asking whether Trump (or Molly Michael or anyone else from Trump’s PAC) showed donors a classified map in a package also showing polling and a faith leader’s support for Trump’s policy in an attempt to raise money doesn’t get you evidence of obstruction. If the map is classified, though, it gets you proof that Trump not only knew he had classified documents, but had turned to profiting off of them.

That’s not a guarantee they’re going to charge 18 USC 793e. It’s a pretty good sign they’re collecting evidence that might support that charge.

Update: CNN has a much more measured story, describing how Jack Smith’s team is locking in the voluntary testimony they got last summer.

The new details come amid signs the Justice Department is taking steps typical of near the end of an investigation.

The recent investigative activity before a federal grand jury in Washington, DC, also includes subpoenaing witnesses in March and April who had previously spoken to investigators, the sources said. While the FBI interviewed many aides and workers at Mar-a-Lago nearly a year ago voluntarily, grand jury appearances are transcribed and under-oath – an indication the prosecutors are locking in witness testimony.

[snip]

The grand jury activity – expected to continue to occur at a frequent clip in the coming weeks – builds upon several known reactions Trump and others around him had to the DOJ’s attempt to reclaim classified records last year, and which prompted the FBI to obtain a judge’s approval to search Mar-a-Lago in August for classified records.

Some of the evidence the DOJ has used to persuade a judge to allow that search is still under seal.

It also notes that Smith is still pursuing how a box including documents with classification marks came to be brought back to Mar-a-Lago after the search.

Since then, the Justice Department has pushed for answers around how a box with classified records ended up in Trump’s office after the FBI search took place.