Mark Meadows’ Middling Path: There Are Several Paths to Prosecute Donald Trump

Two things happened over the weekend that may provide more clarity about Mark Meadows’ fate in the twin Trump investigations in which he’s implicated.

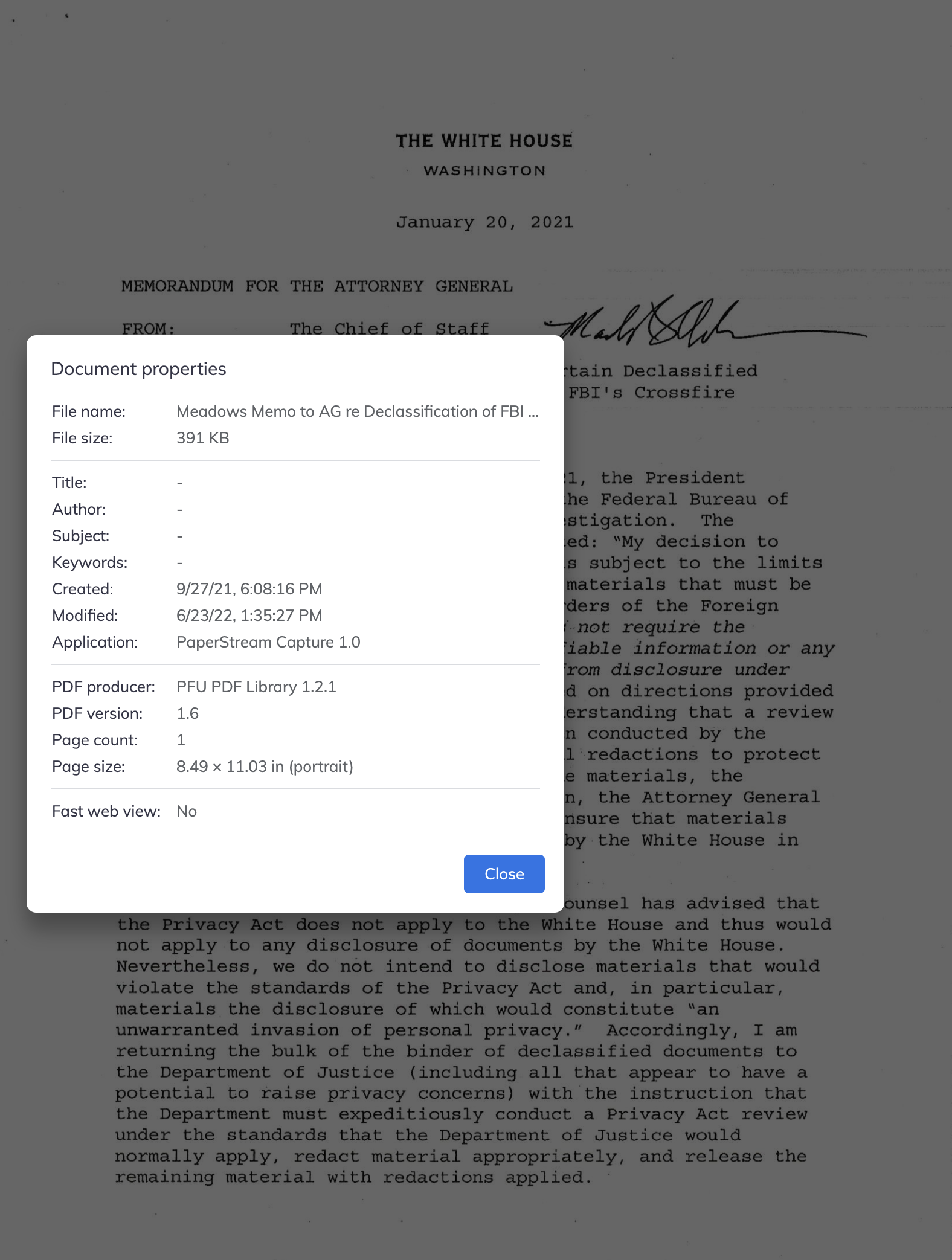

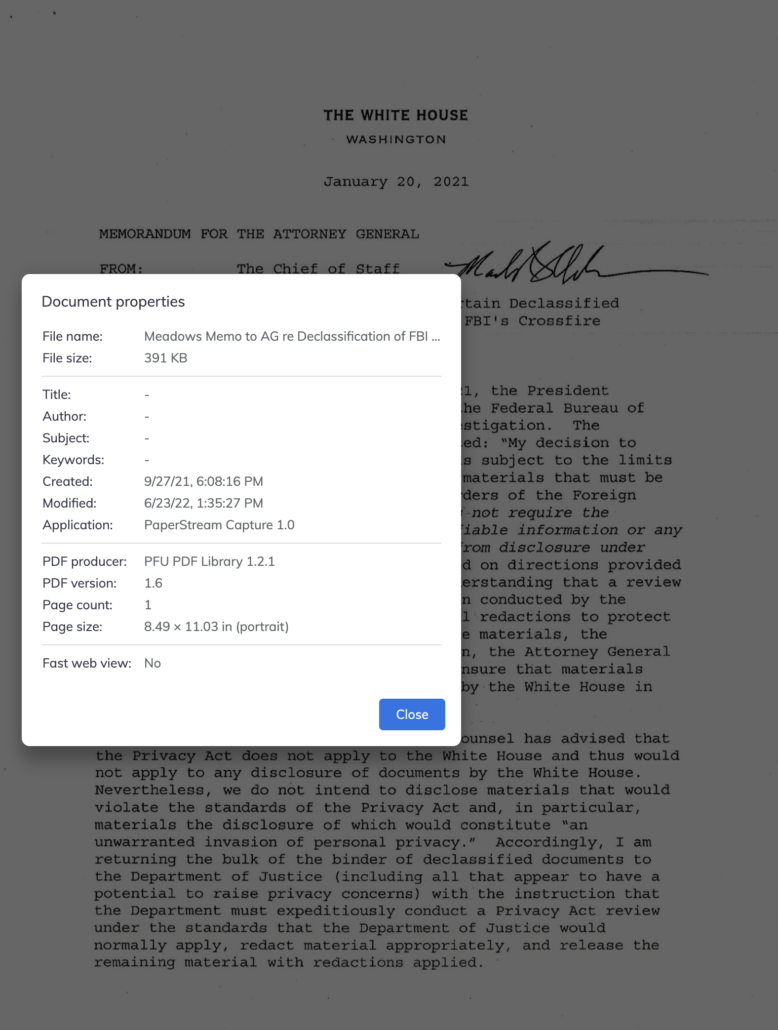

Second in terms of order but I’ll deal with it first, ABC had a big scoop about key parts of his testimony in the stolen documents case. There are four key disclosures about Meadows’ testimony.

- Meadows knew of no standing order to declassify documents

- He was not involved in packing boxes, didn’t see Trump doing so, and wasn’t aware Trump had taken classified documents

- Meadows offered to sort through boxes of documents after NARA inquired about them in May 2021, but Trump declined the offer

- Meadows ultimately backed his ghostwriter’s account that the Iran document that Trump described to Meadows’ ghost-writer was on the couch in front of him at the time of the exchange

The circumstances around Meadows’ testimony about his ghost-writer are the most telling. As ABC describes it, his ghost-writer sent him a draft that conflicted with the final copy of his book. That draft described that when Trump boasted about an Iran document he could use to prove Mark Milley wrong, it was in front of him on the couch. After receiving the draft, Meadows edited out the account that would provide proof Trump was sharing a classified document at Bedminster.

But a draft version of the passage initially sent to Meadows by his ghostwriter, which was reviewed by ABC News, more directly referenced the document allegedly in Trump’s possession during the interview.

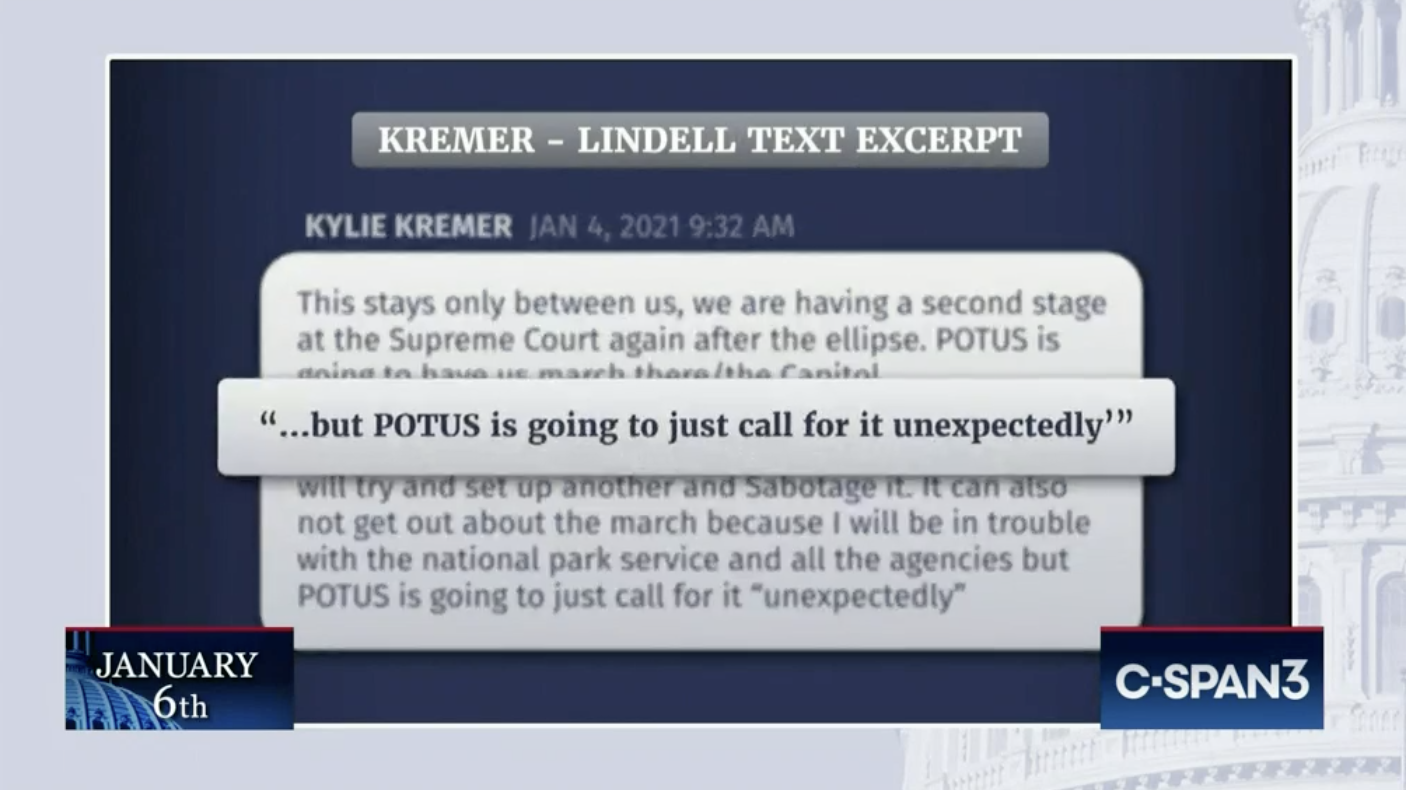

“On the couch in front of the President’s desk, there’s a four-page report typed up by Mark Milley himself,” the draft reads. “It shows the general’s own plan to attack Iran, something he urged President Trump to do more than once during his presidency. … When President Trump found this plan in his old files this morning, he pointed out that if he had been able to make this declassified, it would probably ‘win his case.'”

Investigators may have found this by obtaining a warrant for Meadows’ email and discovering it as a clearly non-privileged attachment, by subpoenaing Meadows’ ghost writer, or both. It would be unsurprising if Jack Smith obtained Meadows’ email from 2020 through the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago, particularly given reports that his account got a privilege review too, and attachments are often the most interesting things obtained from cloud warrants.

The discrepancy between the draft and the final — hinting that Meadows recognized the document to be particularly sensitive — may have driven investigative focus on the document, leading Smith to obtain several recordings of the conversation and ultimately testimony sufficient to charge Trump’s willful retention of it in the superseding indictment.

Just as significantly, for a read of Meadows’ posture towards the dual investigations into Trump: ABC describes that his testimony changed. At some unspecified original interview (by context it appears to have been before the MAL search), Meadows said that he edited that passage because he didn’t believe it. But, apparently in that first interview, he conceded that if Trump did have the document in Bedminster to share with his ghost-writer, it would be problematic.

Sources told ABC News that Meadows was questioned by Smith’s investigators about the changes made to the language in the draft, and Meadows claimed, according to the sources, that he personally edited it out because he didn’t believe at the time that Trump would have possessed a document like that at Bedminster.

Meadows also said that if it were true Trump did indeed have such a document, it would be “problematic” and “concerning,” sources familiar with the exchange said.

But then Meadows’ own testimony changed — possibly at the April grand jury appearance mentioned by ABC.

Meadows said his perspective changed on whether his ghostwriter’s recollection could have been accurate, given the later revelations about the classified materials recovered from Mar-a-Lago in the months since his book was published, the sources said.

Meadows’ explanation for his changed testimony is not all that credible. It sounds like, as he came to understand how solid the case against Trump was, he became less interested in exposing himself to legal troubles by protecting him.

But for Meadows’ purposes, it likely doesn’t have to be. Meadows was not a direct witness to this incident. After prosecutors spent much of the spring fleshing out what happened here, it seems, Meadows conceded the points that were necessary. And the concession may well have been key to the inclusion of the document in the indictment(s): because it meant a witness who might otherwise have provided exculpatory testimony was locked into testimony that did not dispute the testimony of the direct witnesses against Trump.

Importantly, this is not the testimony of a cooperating witness. It is the testimony of someone prosecutors have coaxed to tell the truth by collecting so much evidence there’s no longer room to do otherwise. And it is testimony, if Meadows provided it at that April grand jury appearance, obtained four months after Fani Willis lost her grand jury as an investigative tool.

Which brings us to Meadows’ motion to dismiss the Georgia charges against him, submitted in federal court in NDGA.

The day after the GA indictment, Meadows’ attorneys filed to have it removed from GA to federal court because he was a senior government official during the events in question; this was expected from him, and still is expected from Trump and Jeffrey Clark. The next day, Judge Steve Jones ruled that he had to hear the challenge — effectively ruling that there was nothing procedurally wrong with Meadows’ demand.

Then Friday, Meadows’ team submitted their motion to dismiss the Georgia charges against him. Again, this was expected. But I also expected the brief to be far stronger than it is. It is an example where a team of superb lawyers argue the law — 19 pages of citations before they finally get around to addressing the alleged facts, and several more pages of law but not facts to follow.

Meadows’ motion makes three arguments about how the law applies to the alleged facts:

- Meadows’ alleged actions in the GA indictment fall within his duties as Chief of Staff

- But for his position as Chief of Staff which required him to remain close to provide advice, he would not have done the actions alleged

- His actions were legal at the federal level

The first two points are closely related and appear in two successive paragraphs. It is true that Meadows’ job was to arrange whatever calls the President wanted to make. And most — but not all — of Meadows’ alleged Georgia acts fit into that kind of thing.

The question is not whether Mr. Meadows was specifically authorized or required to do each act, but whether they fall within “the general scope of [his] duties.” Baucom, 677 F.2d at 1350. They surely do. As noted, those duties included information-gathering and providing close and confidential advice to the President. Moreover, as explained below, the State’s characterization of one of these acts as violating state law is wholly irrelevant. See Part II.B, infra. Stripped of the State’s gloss, the underlying facts entail duties with the core functions of a Chief of Staff to the President of the United States: arranging or attending Oval Office meetings, contacting state officials on the President’s behalf, visiting a state government building, and setting up a phone call for the President with a state official. Those activities have a plain connection to his official duties and to the federal policy reflected in establishing the White House Office. [my emphasis]

From there, Meadows argues that if he weren’t Chief of Staff to epic scofflaw Donald Trump, he wouldn’t have been doing these unlawful things for Donald Trump, and if he had simply left the room to object, then he wouldn’t be in the room to provide close and confidential advice.

The “nexus” is readily apparent. Only by virtue of his Chief of Staff role was Mr. Meadows involved in the conduct charged. Put another way, his federal position was a but-for cause of his alleged involvement. Moreover, if Mr. Meadows had absented himself from Oval Office meetings or refused to arrange meetings or calls between the President and governmental leaders, that would have affected his ability to provide the close and confidential advice that a Chief of Staff is supposed to provide. It is inescapable that the charged conduct arose from his duties and was material to the carrying out of his duties, providing more than merely “some nexus.”

Thus far (and ignoring that not all of the charged conduct in Georgia qualifies), this argument actually makes perfect sense for the removal and dismissal argument. Several of the actions charged against Meadows in Georgia really are about arranging meetings and phone calls for the President.

And the argument that Meadows had to stick around to provide advice is stronger than you might think.

It’s where Meadows’ team argues that his actions were legal at the federal level where, in my opinion, the argument starts to collapse — but also where this filing hints at more about Meadows’ strategy for avoiding charges himself.

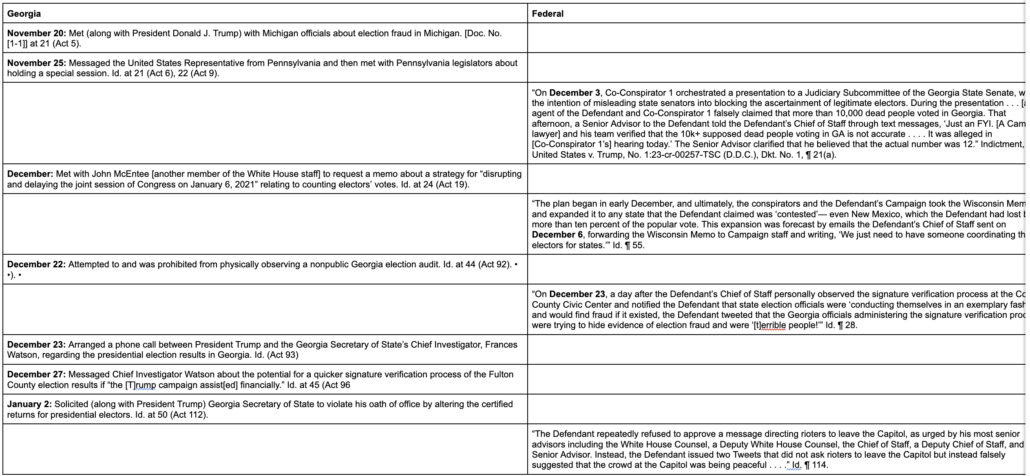

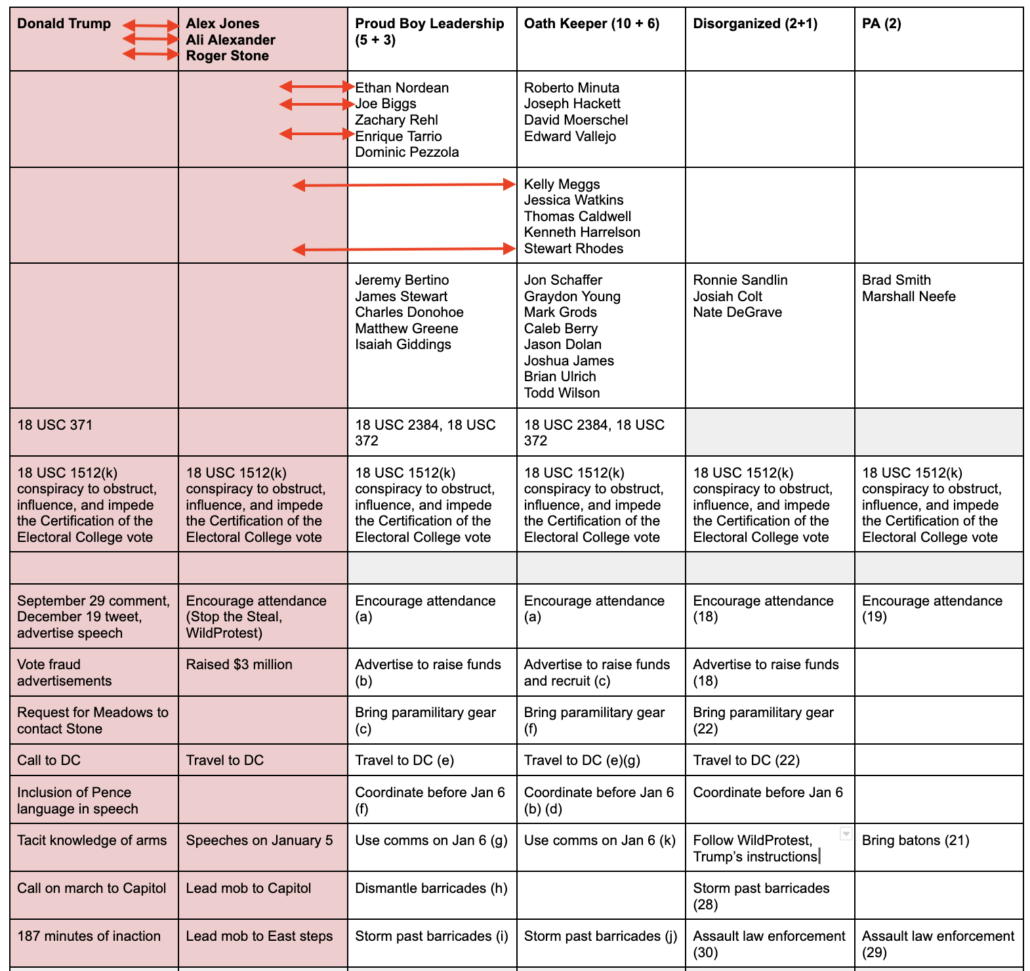

Meadows team recites the alleged Georgia acts as Judge Jones has characterized them on page 19 and then directly quotes the references to Meadows in the federal indictment on page 26. It helps to read them a table together:

There’s an arc here. The early acts in both indictments might be deemed legal information gathering. After that, in early December, Meadows takes two actions, one alleged in Georgia and the other federally, both of which put him clearly in the role of a conspirator, neither of which explicitly involves Trump as charged in the Georgia indictment. Meadows:

- Asks Johnny McEntee for a memo on how to obstruct the vote certification

- Orders the campaign to ensure someone is coordinating the fake electors

The events on December 22 and 23, across the two indictments, are telling. Meadows flies to Georgia and, per the Georgia indictment, attempts to but fails to access restricted areas. Then he flies back to DC and, per the federal indictment, tells Trump everything is being done diligently. Then Meadows arranges and participates in another call. Both in a tweet on December 22 and a call on December 23, Trump pressures Georgia officials again. For DOJ’s purposes, the Tweet is going to be more important, whereas for Georgia’s purposes, the call is more important. But with regards his argument for removal and dismissal, Meadows would argue that he used his close access to advise Trump that Georgia was proceeding diligently.

On December 27, Meadows calls and offers to use campaign funds to ensure the signature validation is done by January 6. This was not Meadows arranging a call so Trump could make the offer himself, it was Meadows doing it himself, likely on behalf of Trump, doing something for the campaign, not the country.

On January 2, Meadows participates in the Raffensperger call, first setting it up then intervening to try to find agreement, but then ultimately pressuring state officials not so much to just give Trump the votes he needs, which was Trump’s ask, but to turn over state data.

Meadows: Mr. President. This is Mark. It sounds like we’ve got two different sides agreeing that we can look at these areas ands I assume that we can do that within the next 24 to 48 hours to go ahead and get that reconciled so that we can look at the two claims and making sure that we get the access to the secretary of state’s data to either validate or invalidate the claims that have been made. Is that correct?

Germany: No, that’s not what I said. I’m happy to have our lawyers sit down with Kurt and the lawyers on that side and explain to my him, here’s, based on what we’ve looked at so far, here’s how we know this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong.

Meadows: So what you’re saying, Ryan, let me let me make sure … so what you’re saying is you really don’t want to give access to the data. You just want to make another case on why the lawsuit is wrong?

Meadows was pressuring a Georgia official, sure, but to do something other than what Trump was pressuring Raffensperger to do. His single lie (he was charged for lying on the call separately from the RICO charge), one Willis might prove by pointing to the overt act from the federal indictment on December 3, when Jason Miller told Meadows that the number of dead voters was not 10,000, but twelve, is his promise that Georgia’s investigation has not found all the dead voters.

I can tell you say they were only two dead people who would vote. I can promise you there were more than that. And that may be what your investigation shows, but I can promise you there were more than that.

But even there, two is not twelve. Meadows will be able to challenge the claim that he lied, as opposed to facilitated, as Chief of Staff, Trump’s lies.

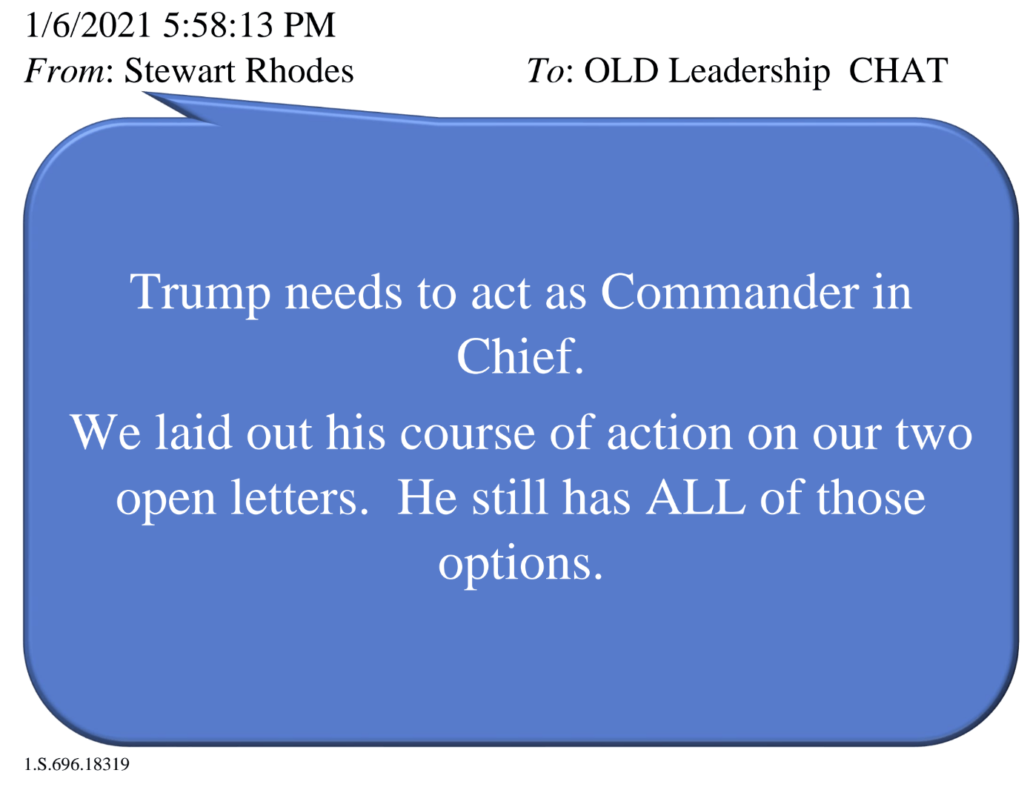

Finally, in an overt act not included in the Georgia indictment, Meadows is among the people on January 6 who (the federal indictment alleges) attempted to convince Trump to call off the mob.

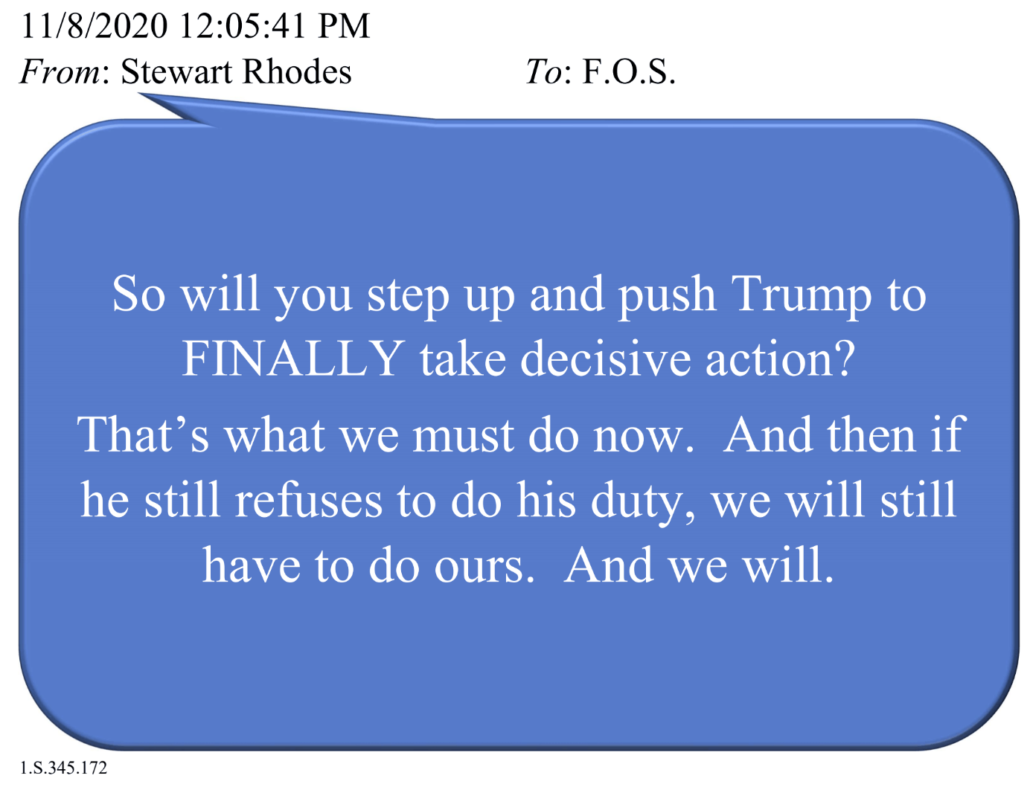

There’s a lot that’s missing here — most notably Meadows’ coordination with Congress and any efforts to coordinate with Mike Flynn and Roger Stone’s efforts more closely tied to the insurrection and abandoned efforts to deploy the National Guard to protect Trump’s mob as it walked to congress. Unless those actions get added to charges quickly, Meadows will be able to argue, in Georgia, that his actions complied with federal law without having to address them. If and when they do get charged in DC, I’m sure Meadows’ attorneys hope, his criminal exposure in Georgia will be resolved.

Of what’s included here, those early December actions — the instruction to Johnny McEntee to find some way to obstruct the January 6 vote certification and the order that someone coordinate fake electors — are most damning. That, plus the offer to use campaign funds to accelerate the signature match, all involve doing campaign work in his role as Chief of Staff. For the federal actions, Jack Smith might just slap Meadows with a Hatch Act charge and end the removal question — but that might not help him, Jack Smith, make his case, because several parts of his indictment rely on exchanges Meadows had privately with Trump, and Meadows is a better witness if he hasn’t been charged with a crime.

Aside from those, Meadows might argue — indeed, his lawyers may well have argued to Jack Smith to avoid being named as a co-conspirator — that his efforts consistently entailed collecting data which he used to try to persuade the then-President, using his access as a close advisor, to adopt other methods to pursue his electoral challenges. Meadows’ lawyers may well have argued that several things marked his affirmative effort to leave the federally-charged conspiracies. In this removal proceeding, I expect Meadows will argue that his actions on the Raffensperger call were an attempt, like several others, to collect more data to use his close access as an advisor to better persuade the then-President to drop the means by which he was challenging the vote outcome.

Meadows’ motion to dismiss is weakest because he doesn’t explain there was any federal policy interest in these actions, much less an executive branch one. The early December activities — the order to Johnny McEntee to find a way to delay the vote certification that both the Constitution and the Electoral College Act reserve to Congress and the order to coordinate fake electors overstep executive authority. How Georgia tallies their vote, which Meadows might otherwise claim were efforts to advise Trump, is reserved to Georgia. There’s no federal policy interest here because Trump’s efforts stomped on the prerogatives of both Congress and the state of Georgia.

The 19 pages of Meadows’ motion to dismiss that discuss the law in isolation of the facts mentions the centrality of federal policy 9 times. The part that discusses the facts uses the word “policy” twice (once, which I’ve bolded, in the Secretary of State passage cited above), but makes no effort whatsoever to describe how these actions — particularly the intervention into matters reserved for Congress and the states — pertained to federal policy. These very good lawyers simply never get around to applying their law about intervention, which pivots on federal policy, to the facts. Instead, their argument relies much more heavily on their claim that, particularly since Meadows hasn’t been charged, Willis won’t be able to prove that Meadows’ actions violated federal law. That argument will only matter if they succeed in getting the case removed to federal court.

Between the overt political nature of three of his actions and the lack of any policy argument, Fani Willis should be able to mount an aggressive challenge to this effort, though the effort is not entirely frivolous and Meadows has very good lawyers even if those lawyers don’t have great facts.

But there’s a bunch more going on here.

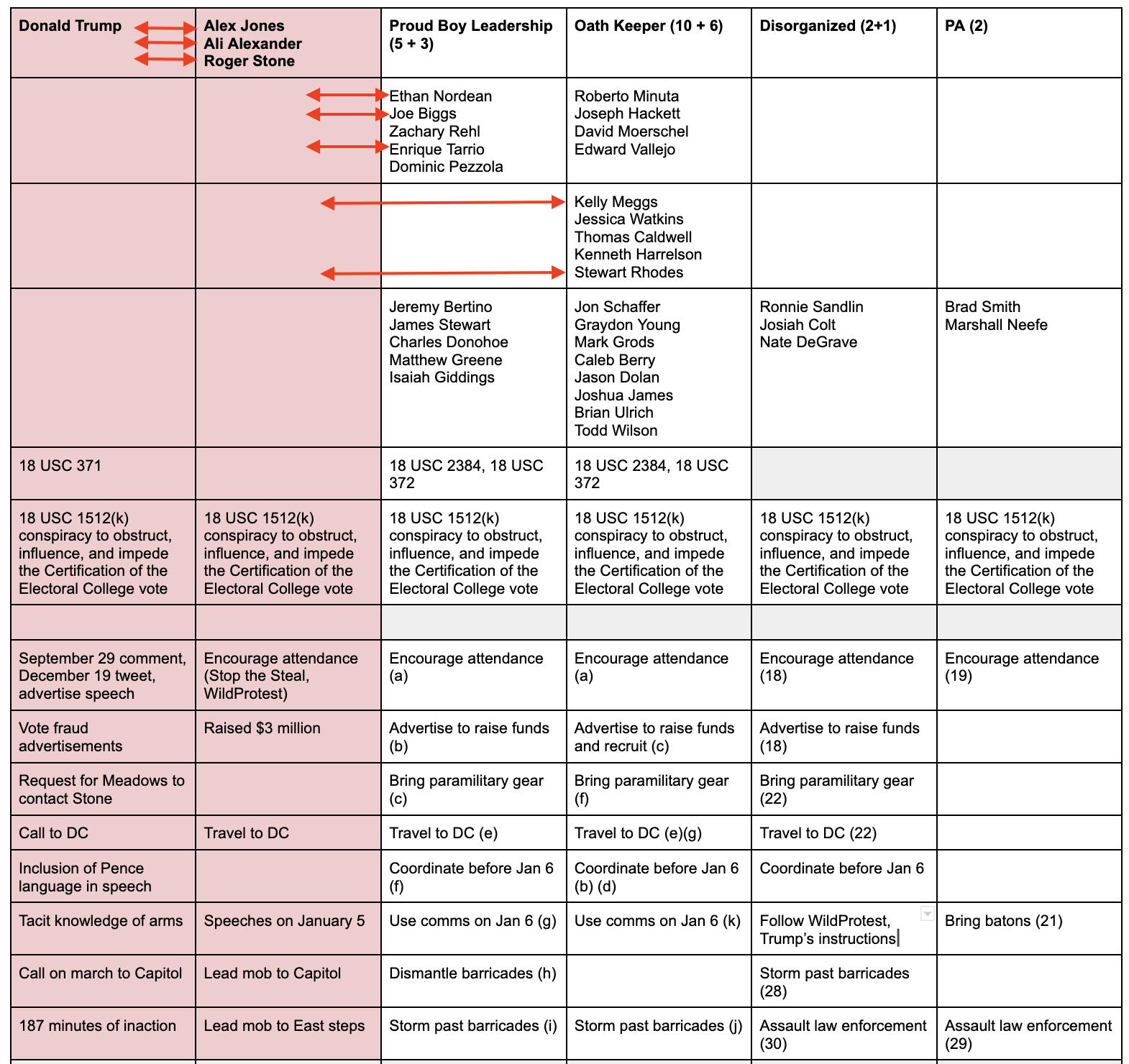

First, as I noted in this post, these prosecutors are using different strategies to get Trump to trial. Willis, who can’t be fired by Trump if he wins in 2024, charged broadly and presumably hopes to use the RICO exposure to flip some of the key conspirators as witnesses against others. Smith, who may have a much shorter clock (but who also has both indicted crimes, but also his financial investigation, to play off each other), has chosen to charge Trump for January 6 alone, with six people identified as unindicted co-conspirators. Smith seems to believe he can introduce all the evidence he needs to convict Trump relying on the hearsay exception just for those six unindicted co-conspirators. He hasn’t made Meadows a co-conspirator, and so is confident he can get Meadows to take the stand and testify to the facts alleged in the indictment.

Until now, the two investigations have not coordinated, though something Willis said in her press conference suggested that perhaps they’ve started talking now, possibly to exchange evidence as permitted under grand jury rules.

Reporter: Have you had any contact with the special counsel about the overlap between this indictment and–

Willis: I’m not going to discuss our investigation at this time.

Plus, they’ve been working on different tracks. Willis had to take overt steps earlier, mostly last summer, and lost her power to compel testimony in December (though she has immunized all but three of the fake electors in recent months). While DOJ was provably doing covert things during Willis’ overt investigation, most of DOJ’s overt acts took place since Willis lost investigative subpoena power.

Willis, who has close ties to January 6 Committee and certain TV lawyers, may well believe their propaganda about how little DOJ was doing, and likewise may share their (provably incorrect, given what we’ve seen in the Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro contempt prosecutions) view that DOJ could have and should have prosecuted Meadows for contempt for blowing off the J6C. She may believe she needs to, and that it is key to her case, to flip Meadows.

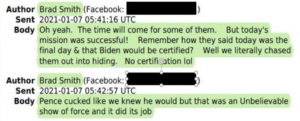

That’s where the ABC report that Meadows changed his testimony about the Iran document is instructive. When he was interviewed in what may have been an interview before the August search of Mar-a-Lago, Meadows said he believed his ghost-writer was incorrect when they claimed Trump had the Iran document in front of him. When Meadows testified before Willis’ grand jury, he offered next to nothing, invoking the Fifth Amendment repeatedly.

Using the Fifth Amendment or citing various legal privileges was a strategy that the grand jury saw from several of the most prominent witnesses, including Trump White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, according to [investigative grand jury foreperson Emily] Kohrs.

“Mark Meadows did not share very much,” she said. “I asked if he had Twitter, and he pled the Fifth.”

Now, at least in the stolen documents probe, Meadows has reversed his prior testimony, explaining that given how damning the facts against Trump are in that case, he thinks his ghost-writer is probably correct about the Iran document being there on the couch.

Meadows also provided compelled, executive privilege-waived testimony since, grand jury testimony obtained before both federal indictments against Trump, grand jury testimony that Smith’s prosecutors used to lock Meadows into a certain story.

These dynamics may explain the curious sequence as portrayed across the two indictments from December 22 and 23, 2020.

On or about the 22nd day of December 2020, MARK RANDALL MEADOWS traveled to the Cobb County Civic Center in Cobb County, Georgia, and attempted to observe the signature match audit being performed there by law enforcement officers from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and the Office of the Georgia Secretary of State, despite the fact that the audit was not open to the public. While present at the center, MARK RANDALL MEADOWS spoke to Georgia Deputy Secretary of State Jordan Fuchs, Office of the Georgia Secretary of State Chief Investigator Frances Watson, Georgia Bureau of Investigation Special Agent in Charge Bahan Rich, and others, who prevented MARK RANDALL MEADOWS from entering into the space where the audit was being conducted. This was an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.

On December 23, a day after the Defendant’s Chief of Staff personally observed the signature verification process at the Cobb County Civic Center and notified the Defendant that state election officials were “conducting themselves in an exemplary fashion” and would find fraud if it existed, the Defendant tweeted that the Georgia officials administering the signature verification process were trying to hide evidence of election fraud and were “[t]errible people!”

On or about the 23rd day of December 2020, DONALD JOHN TRUMP placed a telephone call to Office of the Georgia Secretary of State Chief Investigator Frances Watson that had been previously arranged by MARK RANDALL MEADOWS. During the phone call, DONALD JOHN TRUMP falsely stated that he had won the November 3, 2020, presidential election “by hundreds of thousands of votes” and stated to Watson that “when the right answer comes out you’ll be praised.” This was an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.

Given what Kohrs said about Meadows’ grand jury appearance, we can be sure that all of the claims in Willis’ indictment come from Georgia witnesses. A bunch of people will testify that Meadows tried to force his way into a restricted area — itself suspicious as hell — and Frances Watson will testify that after Meadows reported back, he arranged a call on which Trump harangued her in such a way that is entirely inconsistent with having been told that Meadows told Trump the Georgia investigators were “conducting themselves in an exemplary fashion.”

Meanwhile, that “exemplary fashion” claim could only have come from Meadows’ grand jury testimony, almost certainly in April. Sandwiched between the two overt acts in the Georgia indictment, it is not all that credible. But we can be sure it is locked in as grand jury testimony.

The degree to which subsequent events, including the Georgia indictment, may discredit Meadows’ federal grand jury testimony likely explains why we’ve gotten the first ever leak as to the substance of Meadows’ testimony, which often serves as a way to telegraph testimony to other witnesses. Several of the things ABC describes him as testifying to — that he had no idea Trump took classified documents and that he offered to sort through everything but Trump refused — seem unlikely. But so long as whoever else could refute that (including Walt Nauta, who helped pack up the boxes) tells the same story, he might get away with improbable testimony.

With January 6, though, it’s far less likely he’ll get away with improbable claims before a grand jury, especially if he fails to get the prosecution removed to federal court.

That explains his rush. It explains why Meadows wants to prevent Trump’s and Clark’s motions for removal from causing any delay in his own, which is currently scheduled to be heard on August 28.

Because if and when any other federal crimes come out, his entire argument starts to collapse, particularly given that he failed to argue there was some policy interest in badgering Georgia officials.

Meadows appears, thus far, to have succeeded with a very tricky approach. He has great lawyers and it may well succeed going forward. But with all the indictments flying, that effort gets far more difficult, particularly given the way the overt acts in the Georgia indictment discredit Meadows’ federal grand jury testimony.

Update: I continue to write “Mar-a-Lago” when I mean Bedminster. Fixed an instance of that here.