Sergey Kislyak, Guccifer 2.0, and Maria Butina Walk into an Election Precinct

The Senate Intelligence Committee released a highly redacted version of their election security report. Much of it focuses on coded descriptions cataloging what happened in different states and what has happened as some states try to prepare better for that kind of election interference in the future; this discussion will be far more useful once reporters have carried out the fairly trivial work of identifying which states are referred to in the discussions.

That discussion also reflects a great deal of underlying tension not at all reflected in some of the early stories on the report. State officials bitched, justifiably, at coverage that doesn’t distinguish between scans and hacks, which fosters the panic that Russia probably hoped to create.

Many state election officials emphasized their concern that press coverage of, and increased attention to, election security could create the very impression the Russians were seeking to foster, namely undermining voters’ confidence in election integrity. Several insisted that whenever any official speaks publicly on this issue, they should state clearly the difference between a “scan” and a “hack,” and a few even went as far as to suggest that U.S. officials stop talking about the issue altogether. One state official said, “Wc need to walk a fine line between being forthcoming to the public and protecting voter confidence.

But Ron Wyden raised concerns that all these state level assessments rely on the states’ own data collection, meaning reports that no vote tallies were changed are probably not as reliable as people claim.

DHS’s prepared testimony at that hearing included the statement that it is “likely that cyber manipulation of U.S. election systems intended to change the outcome of a national election would be detected.” The language of this assessment raises questions, however, about DHS’s ability to identify cyber manipulation that could have affected a very close national election, particularly given DHS’s acknowledgment of the “possibility that individual or isolated cyber intrusions into U.S. election infrastructure could go undetected, especially at local levels.”‘^ Moreover, DHS has acknowledged that its assessment with regard to the detection of outcome-changing cyber manipulation did not apply to state-wide or local elections.

(U) Assessments about manipulations of voter registration databases are equally hampered by the absence of data. As the Committee acknowledges, it “has limited information on the extent to which state and local election authorities carried out forensic evaluation of registration databases.”

That is, we don’t actually know what happened in 2016, because so few states were collecting that data, and it remains true that few states are auditing their elections.

Perhaps one of the most interesting details about 2016, however, involves the Russian government’s efforts to get permission to act as election observers, something that shows up two times in the report. It appears that Russia went first to State, and then to localities.

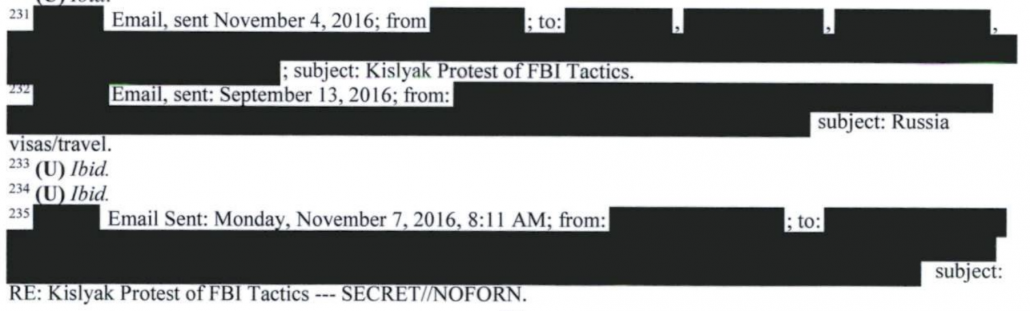

The Russian Embassy placed a formal request to observe the elections with the Department of State, but also reached outside diplomatic channels in an attempt to secure permission directly from state and local election officials. ” 37 In objecting to these tactics, then-Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Victoria Nuland reminded the Russian Ambassador that Russia had refused invitations to participate in the official OSCE mission that was to observe the U.S. elections.38

There’s another, heavily redacted discussion of this later in the report, but that unredacted discussion does say that Russia was seeking access to voting sites in September, and that no one ever figured out what Russia planned to do.

Department of State were aware that Russia was attempting to send election observers to polling places in 2016. The true intention of these efforts is unknown.

[snip]

The Russian Embassy placed a formal request lo observe the elections with the Department of State, but also reached outside diplomatic channels in an attempt to secure permission directly from state and local election officials.”‘ For example, in September 2016, the State 5 Secretary of State denied a request by the Russian Consul General to allow a Russian government official inside a polling station on Election Day to study the U.S. election process, according to State 5 officials.

But the footnotes make it clear that Ambassador Sergey Kislyak was bitching about the response all the way up to November 7.

That section immediately precedes a partly redacted discussion of a possible Russian effort to sow misinformation about voter fraud.

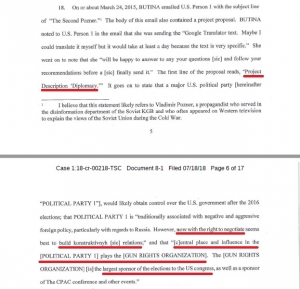

What the report does not say, in unredacted form, is how Kislyak’s formal efforts overlap with two other Russian efforts. First, there’s the discussion Maria Butina and Aleksandr Torshin had about whether she should serve as an election observer.

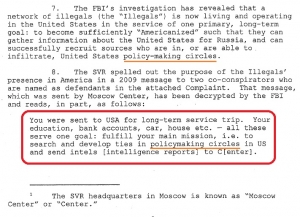

Following this October 5, 2016 Twitter conversation, BUTINA and [Aleksandr Torshin] discussed whether BUTINA should volunteer to serve as a U.S. election observer from Russia and agreed that the risk was too high. [Torshin] expressed the opinion that the “risk of provocation is too high and the ‘media hype’ which comes after it,” and BUTINA agreed by responding, “Only incognito! Right now everything has to be quiet and careful.”

Then there’s Guccifer 2.0’s announcement, at a time when Kislyak was bitching that Russia had been denied access to election sites, that he was going to serve as a (nonsensical) FEC election observer, watching the vulnerabilities in

SSCI doesn’t go there, but at a minimum, Guccifer 2.0’s disinformation paralleled an overt effort by the Russian state, one that Butina considered, but decided against, joining.

Of course, as I’ve noted before, it wasn’t just Russian entities volunteering to act as election observers so as to sow chaos. Where Russia threatened to do so, Roger Stone succeeded.

As I disclosed last July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.