As I disclosed last month, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.

In my post outlining all the investigative steps the Mueller team has taken with Roger Stone since Rick Gates flipped, I pointed to some things that seem to relate to questions Mueller has asked.

That’s one reason why the circumstances of Stone’s flip-flop in early August 2016, in which Stone went from admitting that the DNC hack was done by Russia to claiming it was not seemly in one day in which he was in Southern California is so important: because he established a contemporaneous claim he has relied on to excuse any coordination with Guccifer 2.0 and WikiLeaks. Given the import of Stone’s flip-flop, I find it interesting that so much of the funding for his SuperPAC came from Southern California, especially from John Powers Middleton. Did he meet with his donors when he orchestrated the flip-flop that makes it harder to argue his discussions and foreknowledge of Guccifer 2.0 and WikiLeaks events count as entering into a conspiracy to break one or several laws?

Whatever the circumstances of that flip-flop, from that point forward, Stone pushed several lines — notably the Seth Rich conspiracy — that would be key to Russian disinformation. A big chunk of his SuperPAC funds also spent on “Stop the Steal,” which may also tie to Russian disinformation to discredit the election.

One of the complexities Mueller may have spent months digging through may be whether and how to hold Stone accountable for willfully participation in disinformation supporting Russia’s larger efforts to swing the election to Donald Trump.

Last week, I started to look more closely at how Stone’s PAC may relate to this. There are, in my opinion, a number of really interesting details about his PAC (which admittedly isn’t dealing with that much money).

That was before, last week, materials in Andrew Miller’s challenge to the subpoena were unsealed, which first revealed Miller wanted a grant of immunity to testify about things pertaining to work he did for Stone’s PAC.

A hearing transcript from June 18 shows that Miller was subpoenaed for information about Stone, as well as key figures in the 2016 hacking of the Democratic National Committee and the public release of Democrats’ emails. According to that transcript, the subpoena seeks information from Miller about WikiLeaks and Assange. WikiLeaks published large volumes of Democrats’ hacked emails during the campaign.

The subpoena also seeks information about Guccifer 2.0 and DCLeaks. Investigators say both were online fronts invented by Russian intelligence operatives to spread the hacked documents. DCLeaks was a website that posted hacked emails of current and former U.S. officials and political aides, while Guccifer 2.0 claimed to be a Romanian hacker.

Miller had asked for “some grant of immunity” regarding financial transactions involving political action committees for which he assisted Stone, according to Alicia Dearn, an attorney for Miller.

On that issue, Miller “would be asserting” his Fifth Amendment right to refuse to answer questions, Dearn said.

As for the hacking and WikiLeaks questions, Dearn said at the hearing, “We don’t believe he has any information” about those topics.

Along with Miller, Kristin Davis also got paid by one of Stone’s PACs. Neither was paid enough to pay for the legal fees they’ve incurred covering their testimony (though a conservative group has paid for Miller’s challenge to his subpoena). Citroen Associate owner John Kakanis, who also testified, got paid more, though maybe not enough to pay for legal representation.

There are a number of notable things about Stone’s PACs that — at least on their face — are not unusual. There is one detail — that the bulk of the expenditures paid a personal injury law firm, one whose family members appear to have served as treasurers of the PACs — that is unusual. Most interesting of all, however, is how Stone’s Stop the Steal PAC’s voter suppression efforts before the election so closely paralleled Russian efforts.

Guy with the Nixon tattoo’s SoCal funding

First, remember the mysterious funding from SoCal aspect to the Watergate scandal? There was good reason for that for Nixon; after all, he was from SoCal. Maybe Stone’s just doing most of his fundraising there for old time’s sake, because more than half the funding of Stone’s Committee to Restore American Greatness PAC (referred as CRAG below) comes in serial donations from John Powers Middleton, the son of the Philadelphia Phillies’ owner, who makes shitty movies. A good number of the other substantial donations come from SoCal too. And two PACs Stone operated in 2016 were run out of a UPS store in Santa Ana, CA.

That Middleton largely bankrolled this PAC is in no way unique or legally problematic (indeed, the numbers involved are much smaller than other such PACs). It is notable, however, that contributions to Stone’s PAC were Middleton’s only contributions in 2015-2016, and (apparently) his only recent FEC tracked political contributions, though Middleton played a big role in a youngish Republican group in his 20s. It’s also odd how he gave installments, including two smaller ones, in the same time period or even on the same day as other more sizable ones.

Robert Shillman’s pass through

The timing of the donations make it clear that the sole campaign contribution Stone’s PAC made — $16,000 in two donations to Trump, which paid for Clear Channel billboards — were pass throughs of San Diego County executive Robert Shillman donations. He’s a big donor to GOP causes, but spent much bigger money on PACs supporting Carly Fiorina ($25,000) and Marco Rubio ($75,000) in the primary. Interestingly, he also maxed out in direct donations to Ron DeSantis in 2015-2016, and is backing Devin Nunes this cycle. For some reason I don’t understand, the FEC recorded the first of those donations, made in August, as a primary donation (that’s true of a number of other smaller donations made in the fall as well). Shillman has also donated to Islamophobic fearmongering in the past.

This pass through is also not unusual, but it is notable for how obvious it is and because the pass through is the only donation to a political campaign in this PAC.

The Personal Injury lawyers in bed with Stone

What is unusual is the centrality of the Costa Mesa office of personal injury lawyers Jensen & Associates in all this. One of the firm’s only lawyers, Erin Boeck, may be the spouse of Brad Boeck, who served as treasurer for two of Stone’s PACs. The principal, Paul Jensen, may be related to Pamela Jensen, who set up Stone’s Women v Hillary PAC.

Jensen & Associates made two loans to CRAG of very specific amounts: 2398.87 and 2610, which were repaid less than a week after the second one was made. And in 2016, CRAG paid the firm almost $100,000, including $20,000 in April when Stop the Steal was set up, $23,700 in four different payments in July 2016, and a $9,500 payment on August 3, when Stone was out in LA claiming to Sam Nunberg to be dining with Julian Assange.

According to its website, Jensen & Associates does things like sue for dog bites, not set up political rat-fucking PACs.

The personal injury lawyers cohabiting with the Clinton dirt CPA

While the Women v Clinton 527 would not be registered by Pamela Jensen until June 2, 2016, the effort to dig up the women at the center of Bill Clinton’s scandals actually started much earlier, on February 1, 2016, when Pamela Jensen CPA would send out a fundraising letter to fund Kathleen Wiley’s mortgage. Pamela Jensen’s CPA address is the same as for Jensen & Associates law firm (though her license expired on December 31, ,2016).

On February 19, 2016, Roger Stone told Alex Jones that Trump himself had donated to the Willey fund, even though it had never raised anywhere close to the $80,000 it listed as a goal.

STONE: Or, short circuit this. Go right to HelpWilley.com. Help Willey, W-i-l-e-e-y (sic). Now the good news is —

JONES: We’re going to tweet that, we’re going to Facebook it right now. We haven’t really done that yet, so we’re going to do that right now. Go ahead, sir.

STONE: I appreciate it. We have raised a substantial amount of money. Trump is himself a contributor — I’m not ready to disclose what he has given. And many, many other people.

JONES: Oh OK, so that GoFundMe is only one thing.

STONE: That is only receptacle and there are –

JONES: OK so the best place to go again is, again —

STONE: HelpWilley.com. Willey spelled W-i-l-l-e-y. HelpWilley.com will take you right to one of our pages. We have numerous receptacles, we have raised substantially more than 3,970, we’re haggling with the mortgage company even as we speak, and I am still hopeful that we can save Kathleen’s home so she can go out on the road and take the fight right to the Clintons.

There are actually two entities here. The STOP RAPE PAC was registered on October 1, 2015. The Women v Clinton 527 was registered in June 2016. Both only ever had enough money to pay the mailbox used for its official address.

The revolving door between Stone’s rat-fucking PACs

Which brings us to another detail that is typical of many PACs.

Stone and his buddies were shifting money back and forth between a 527 named Stop the Steal and CRAG.

CRAG was set up in 2015 (though it didn’t file its FEC paperwork until July 2016). Stop the Steal was set up on April 6 2016, at a time when Trump was worried about knocking down a Convention rebellion (which is why Paul Manafort first got hired). The day it was set up, CRAG transferred $50,000 to Stop the Steal. Though by April 13, Stop the Steal was claiming to want to fundraise $262,000, money that never showed up in Stop the Steal’s IRS filings, if it did raise that kind of money.

Among the things Mueller questioned Michael Caputo about were meetings he and Rick Gates had with Stone. One of those meetings, to discuss the effort to ensure the loyalty of GOP delegates, took place in the weeks after Stop the Steal was first set up.

“I only have a record of one dinner with Rick Gates,” he said, adding that the guest list included two other political operatives: Michael Caputo, a former Trump campaign aide who was recently interviewed by Mr. Mueller’s investigators, and Paul Manafort, who soon after took over as chairman of Mr. Trump’s campaign. But Mr. Manafort canceled at the last minute, and Mr. Gates, his deputy, attended in his place.

Mr. Stone said the conversation during the dinner, which fell soon after the New York primary in April 2016, was about the New York State delegate selection for the Republican National Convention. The operatives expressed concern about whether delegates, at a time of deep division among Republicans, would be loyal to Mr. Trump’s vision for the party, Mr. Stone said.

Stop the Steal’s 527 filings show two expenditures for rallies in this earlier incarnation.

On July 12, 2016, Stop the Steal transferred $63,000 to CRAG. Its IRS paperwork doesn’t appear to show how, having made expenditures and raised negligible money in the interim period, it had that much money to return to CRAG, suggesting it may not have reported all its donations.

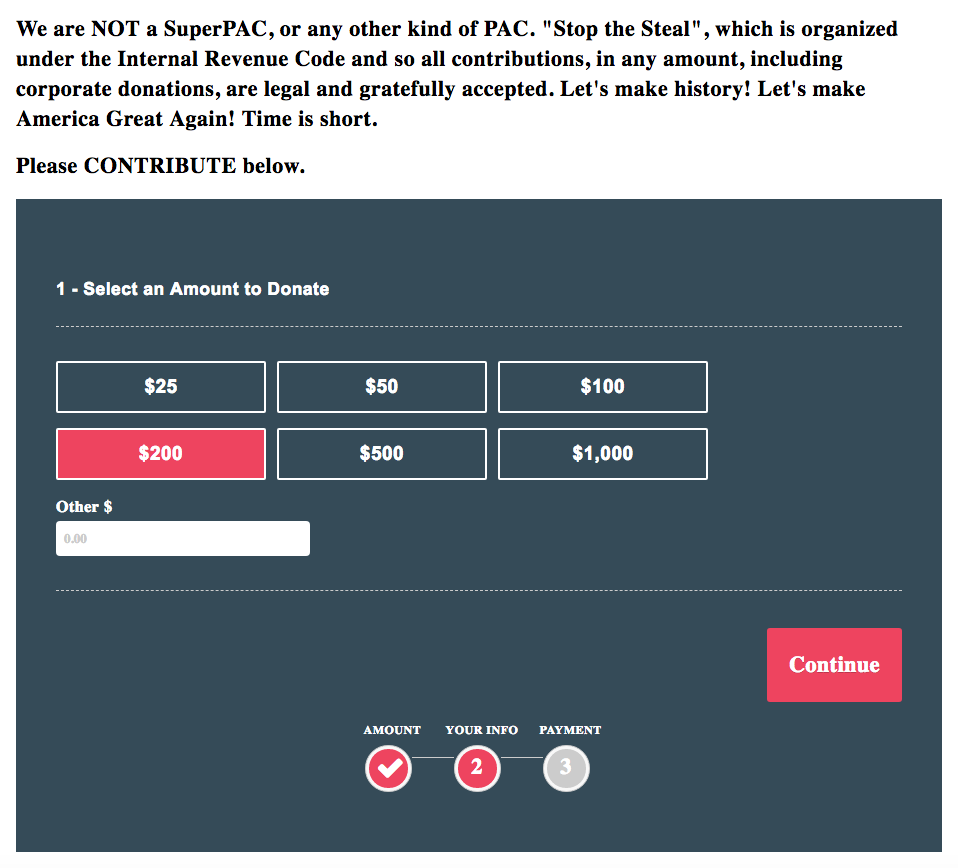

In the fall, Stop the Steal was repurposed to conduct Stone’s voter suppression efforts, including an effort to register “exit pollers” based on the inflammatory rhetoric about rigging the election that Trump had been pushing for some time, with an added focus on the voting machines.

Help us to reveal the TRUTH! Be an Exit Poller! Register Now!

Donald Trump thinks Hillary Clinton and the Democrats are going to steal the next election. “I’m afraid the election is going to be rigged, I have to be honest,” he told a campaign rally last week.

The issue is both voter-fraud and election theft through manipulation of the computerized voting machines. The truth is both parties have used these DIEBOLD/ PES voting machines to rig results of elections at the state and federal election. The party in power in a given state controls the programming of the voting machines.

Here is how easy it is to rig these machines:

We now know, thanks to the hacked e-mails from the Democratic National Committee that the Clintons had to cheat and rig the system to steal the Democratic nomination from Bernie Sanders. Why wouldn’t they try to steal the election from Donald Trump?If this election is close, THEY WILL STEAL IT.

The Washington Post even ran an editorial saying it was “impossible” to steal an election. Then, incredibly, Barrack Obama called Donald Trump’s concerns about a rigged election “ridiculous.”

Plus they intend to flood the polls with illegals. Liberal enclaves already let illegals vote in their local and state elections and now they want them to vote in the Presidential election.

What can we do to stop this outrageous steal? We must step up to the plate and do this vital job? That’s why I am working with a staticians attorneys and computer experts to find and make public any result which has been rigged

We at THE EMERGENCY COMMITTEE TO STOP THE STEAL WILL:

– Demand inspection of the software used to program the voting machines in every jurisdiction prior to the beginning of voting by an independent and truly non-partisan third party.

– Conduct targeted EXIT-POLLING in targeted states and targeted localities that we believe the Democrats could manipulate based on their local control, to determine if the results of the vote have been skewed by manipulation.

– Retain the countries foremost experts on voting machine fraud to help us both prevent and detect voting machine manipulation by putting in a place to monitor polling, review the results and compare them to EXIT POLLS we must conduct.

– Recruit trained poll watchers for the key precincts in key states to monitor voting for fraud. Between the Trump campaign and our efforts we believe we can cover every precinct in the crucial states.

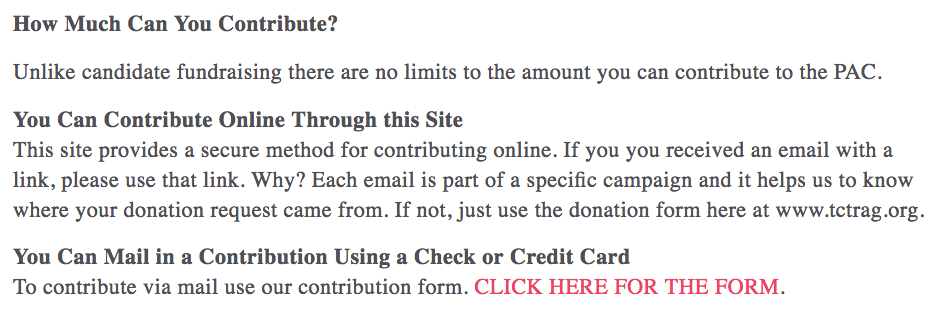

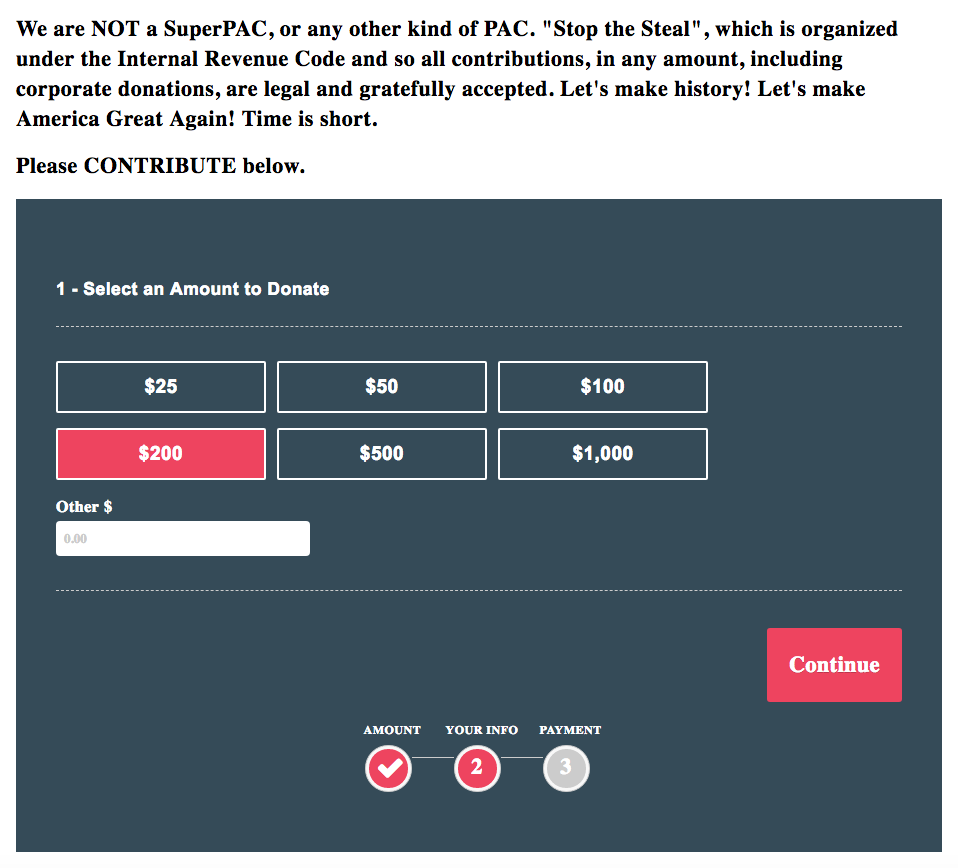

The effort also included a fundraising aspect, with a stated goal of raising $1 million. Stop the Steal reported $20,894 in small donations for the period covering the election, with $32932 reported for the year-to-date.

The Democratic Party sued Stone, Trump, and the state Republican parties in four swing states to get a Temporary Restraining Order against these activities.

The revolving door was actually a mislabeled front door

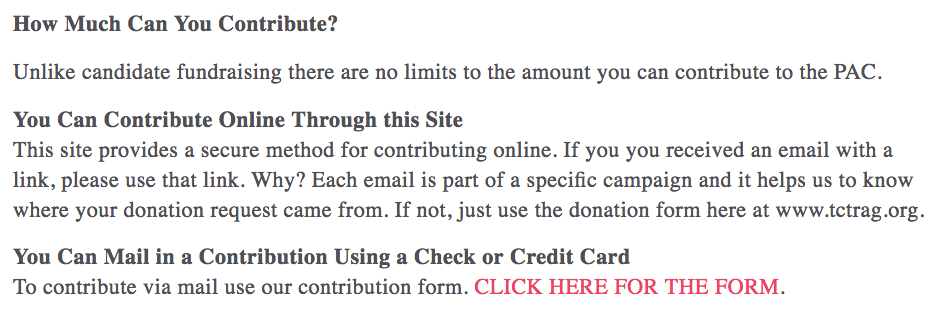

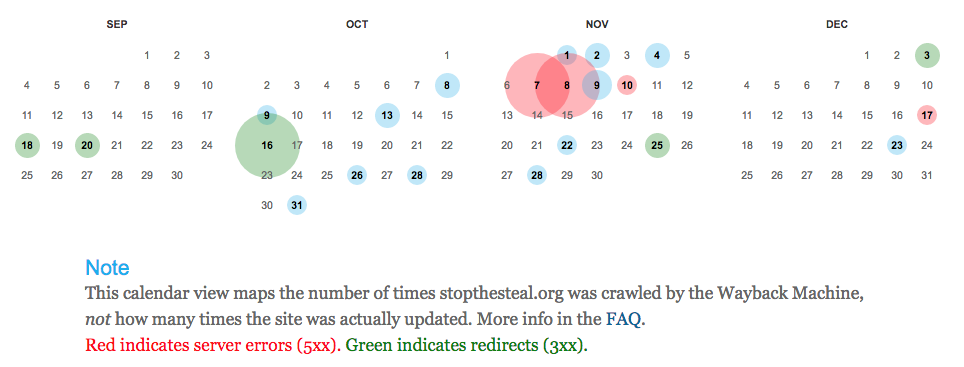

Now that I’m looking at the saved versions of Stone’s various websites, it’s clear he wasn’t segregating the fundraising for them, and I wonder whether some of his email fundraising involved other possible campaign finance violations. For example, here’s the Stop the Steal site as it existed on March 10, 2016. It was clearly trying to track fundraising, carefully instructing people to respond to emails if they received one. But it claimed to be TCTRAG (what I call CRAG), even though the incoming URL was for Stop the Steal.

That remained true even after Stop the Steal was formally created, on April 10. Even after the website changed language to disavow Stop the Steal being a PAC by April 23, the fundraising form still went to TCTRAG (what I call CRAG), a PAC.

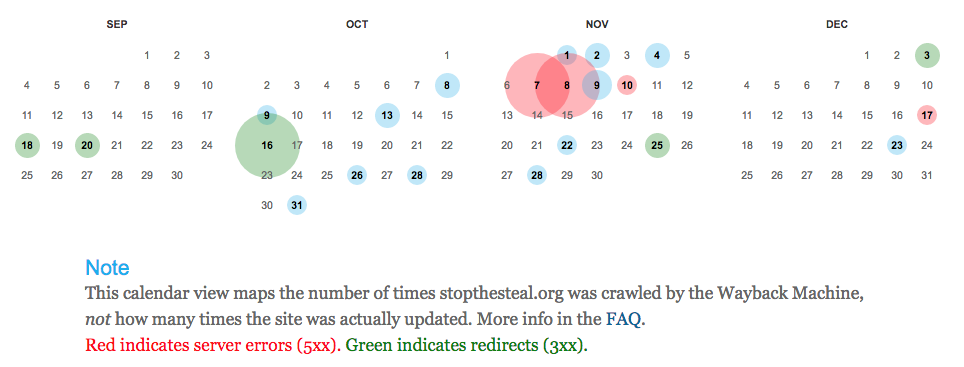

And that remained true on May 12, when the site was aiming to raise $262,000. When the campaign had shifted to voter suppression targeted Democrats (this is October 16), the entire site redirected to a TCTRAG nation-builder site. Though it appears the Stop the Steal URL was returning both a direct site and a redirect (and it appears it was either hammered, or pretending to be hacked, on election day).

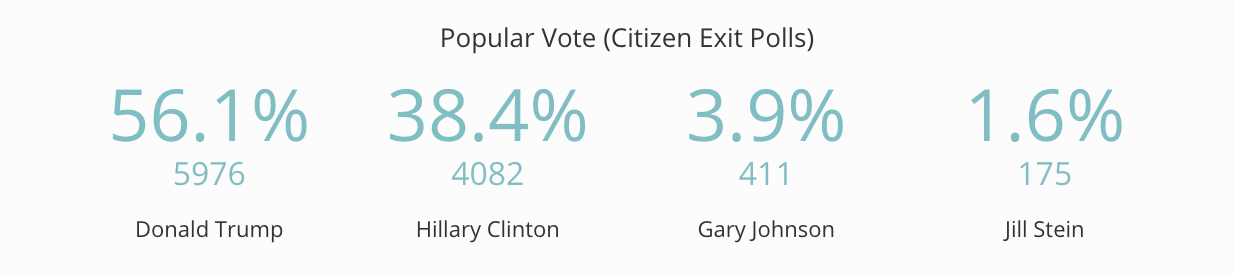

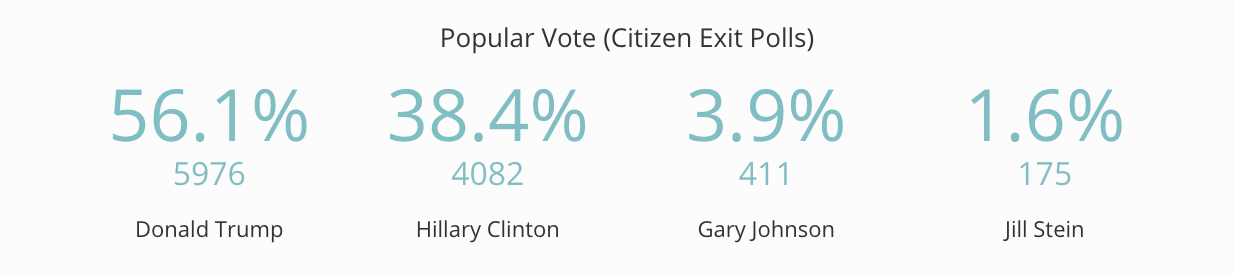

Here are the results of Stone’s “citizen exit polls” on November 9, a totally unscientific data point to “prove” that Hillary had stolen the election.

The parallel Russian and rat-fucker effort to suppress the vote

Stone’s voter suppression effort is not surprising. It’s the kind of thing the rat-fucker has been doing his entire life.

Except it’s of particular interest in 2016 because of the specific form it took. That’s because two aspects of Stone’s voter suppression efforts paralleled Russian efforts. For example, even as Stone was recruiting thousands of “exit pollers” to intimidate people of color, Guccifer 2.0 was promising to register as an election observer, in part because of the “holes and vulnerabilities” in the software of the machines.

I’d like to warn you that the Democrats may rig the elections on November 8. This may be possible because of the software installed in the FEC networks by the large IT companies.

As I’ve already said, their software is of poor quality, with many holes and vulnerabilities.

I have registered in the FEC electronic system as an independent election observer; so I will monitor that the elections are held honestly.

I also call on other hackers to join me, monitor the elections from inside and inform the U.S. society about the facts of electoral fraud.

More interesting still, the GRU indictment makes it clear that GRU’s information operation hackers were probing county electoral websites in swing states as late as October 28.

In or around October 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators further targeted state and county offices responsible for administering the 2016 U.S. elections. For example, on or about October 28, 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators visited the websites of certain counties in Georgia, Iowa, and Florida to identify vulnerabilities.

Whether or not GRU ever intended to alter the vote, Russia’s propagandists were providing the digital “proof” that Republicans might point to to sustain their claims that Democrats had rigged the election.

This is a line that Wikileaks also parroted, DMing Don Jr that if Hillary won his pop should not concede.

Hi Don if your father ‘loses’ we think it is much more interesting if he DOES NOT conceed [sic] and spends time CHALLENGING the media and other types of rigging that occurred—as he has implied that he might do.

Does Mueller have the proof this parallel effort was coordination?

As I noted, the public record makes it clear these are, at the least, complementary parallel efforts. But Mueller’s relentless focus on Stone — and his inclusion of Wikileaks and Guccifer 2.0 in the subpoena to Andrew Miller (whose research on voter fraud is one of the things Mueller wants to present to the grand jury) — suggests he thinks this is not so much a parallel effort, but a coordinated one.

h/t to Susan Simpson and Adam Bonin for help with understanding the numbers here.

Update: TC notes that there are 14 instances of known Russian troll accounts hashtagging Stop the Steal. The examples are most interesting for the date range: the earliest is September 10, 2016; the most recent is February 24, 2017. And they certainly were prepped to go on election day and the day after.

Update: You can pull up the times where Roger Stone’s twitter account hashtagged Stop the Steal in the Trump Twitter archive. Of note, the first instance in the fall campaign was August 4, when Stone was out in LA claiming he was dining with Assange. Two of the earlier incarnations @ Manafort. Also of note are the differing platforms the tweets come from — including Twitter’s web client, TweetDeck, Twitter for iPhone, and Mobile Web — as that may suggest some of the associates who’ve been interviewed did the tweeting.

Update: MS notes that Stone was talking about rigged voting machines as early as July 29.

Update: Added section dedicated to Pamela Jensen’s Bill Clinton focused organizations and moved Stone website details into body of text. H/t Liberty_42 for the former.

Timeline

September 2, 2011: Pamela Jensen registers Should Trump Run 527 with Michael D Cohen listed as President

October 1, 2015: Pamela Jensen registers STOP RAPE PAC by loaning it enough money to pay for a mailbox

November 10, 2015: Jensen & Associates loans $2,398.87 to CRAG

November 10, 2015: CRAG pays Entkesis 2373.87

December 24, 2015: CRAG pays Newsmax 10803.55

December 31, 2015: CRAG pays Newsmax 1585.76

February 1, 2016: Pamela Jensen sends out fundraising letter to World Net Daily pushing Kathleen Wiley’s mortgage fundraiser

February 4, 2016: Jensen & Associates loans $2,610 to CRAG

February 10, 2016: Loans from Jensen & Associates repaid

February 19, 2016: Roger Stone tells Alex Jones that Donald Trump has donated to the Kathleen Willey fundraiser, even though it had raised less than $4,000 at that time

March 1, 2016: John Powers Middleton Company donates $150,000 to CRAG

March 6, 2016: First tweet in spring Stop the Steal campaign

March 9, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $50,000 to CRAG

March 11, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $25,000 to CRAG

March 14, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $25,000 to CRAG

April 6, 2016: Stone (Sarah Rollins) establishes Stop the Steal in same UPS post box as CRAG

April 6, 2016: CRAG gives $50,000 to Stop the Steal

April 6, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $11,000

April 6, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $9,000

April 6, 2016: Stone tweets Stop the Steal toll free line to “report voter fraud in Wisconsin” primary

April 12, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $60,000 to CRAG

April 13, 2016: Stop the Steal pays Sarah Rollins $386.72

April 14, 2016: CRAG pays Tim Yale $9,000

April 14, 2016: Stop the Steal pays Jim Baker $1,500 in “expense reimbursements for rally”

April 15, 2016: Stop the Steal pays Sarah Rollins $500

April 15, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $15,000 to CRAG

April 15, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $2,000 to CRAG

April 15, 2016: $1,000 refunded to John Powers Middleton

April 18, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $1,000 to CRAG

April 18, 2016: CRAG pays Citroen Associates $40,000

April 25, 2016: CRAG pays Paul Nagy $2,500

April 25, 2016: CRAG pays Sarah Rollins $500 plus $41.66 in expenses

April 29, 2016: John Powers Middleton donates $50,000 to CRAG

May 1, 2016: Last Stone tweet in spring Stop the Steal campaign

May 2, 2016: CRAG pays Sarah Rollins $800

May 4, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $5,000

May 13, 2016: CRAG pays Sarah Rollins 93.50

May 15, 2016: Stop the Steal pays Sarah Rollins $500

May 16, CRAG pays Andrew Miller $2,000

May 16, 2016: CRAG pays Citroen Associates $10,000

May 16, 2016: CRAG pays Sarah Rollins $400

May 16, 2016: CRAG pays Kathy Shelton $2,500

May 24, 2016: Stone PAC RAPE PAC, aka Women v Hillary, announced

June 2, 2016: Pamela Jensen sets up Women v Hillary PAC out of a different mailboxes location in Costa Mesa (again, this only ever showed enough money to pay for the mailbox used as its address)

June 7, 2016: FEC informs CRAG it must submit filings by July 12, 2016

June 7, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $4,790

June 8, 2016: Stop the Steal pays Paul Nagy $800 in “expense reimbursements for rally”

June 17, 2016: CRAG pays Andrew Miller $3,000

July 5, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $14,500

July 6, 2016: CRAG pays Michelle Selaty $10,000

July 6, 2016: CRAG pays Drake Ventures $12,000

July 11, 2016: CRAG pays Cheryl Smith $4,900

July 12, 2016: Stop the Steal gives $63,000 to CRAG

July 12, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $7,200

July 15, 2016: CRAG pays Jason Sullivan $1,500

July 18, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $7,500

July 20, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $3,000

July 29, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $6,000

August 1, 2016: CRAG pays Andrew Miller $4,000; Stone flies from JFK to LAX

August 2, 2016: Stone dines with Middleton at Dan Tanas in West Hollywood (h/t Laura Rozen)

August 3, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $9,500

August 3, 2016: CRAG pays Josi & Company $2,500

August 3-4, 2016: Stone takes a red-eye from LAX to Miami

August 4, 2016: Stone flip-flops on whether the Russians or a 400 pound hacker are behind the DNC hack and also tells Sam Nunberg he dined with Julian Assange; first tweet in the fall StopTheSteal campaign

August 5, 2016: Stone column in Breitbart claiming Guccifer 2.0 is individual hacker

August 9, 2016: CRAG pays Jason Sullivan $1,500

August 15, 2016: CRAG pays Jensen & Associates $19,500

August 29, 2016: CRAG pays Law Offices of Michael Becker $3,500

August 31, 2016: Robert Shillman gives $8,000 to CRAG

September 12, 2016: CRAG gives $8,000 to Donald Trump

September 14, 2016: CRAG pays $3,000 to Citroen Associates

September 21, 2016: Robert Shillman gives $8,000 to CRAG

September 22, 2016: CRAG gives $8,000 to Donald Trump

October 4, 2016: Stone tells Bannon to get Rebekah Mercer to send money for his “the targeted black digital campaign thru a C-4”

Following October 5, 2016: Mariia Butina and Aleksandr Torshin discuss whether she should serve as a US election observer; Torshin suggests “the risk of provocation is too high and the ‘media hype’ which comes after it,” but Butina suggests she would do it “Only incognito! Right now everything has to be quiet and careful.”

October 13, 2016: Stop the Steal pays Andrew Miller $5,000

October 23, 2016: Stone tweets out message saying Clinton supporters can “VOTE the NEW way on Tues. Nov 8th by texting HILLARY to 8888”

October 28, 2016: GRU officer Anatoliy Kovalev and co-conspirators visit websites of counties in GA, IA, and FL to identify vulnerabilities

October 30, 2016: Ohio Democratic Party sues Ohio Republican Party to prevent Stop the Steal voter suppression; Democrats also sue in NV, AZ, and PA

November 3, 2016: Filings in ODP lawsuit describing Stop the Steal (declaration, exhibits)

November 4, 2016: Judge James Gwyn issues Temporary Restraining Order against Trump, Stone, and Stop the Steal

November 4, 2016: Guccifer 2.0 post claiming Democrats may rig the elections

November 7, 2016: Sixth Circuit issues a stay in OH TRO

December 14, 2016: Women versus Hillary gives $158.97 to CRAG

December 19, 2016: Stop the Steal pays $5,000 to Alejandro Vidal for “fundraising expenses”

December 19, 2016: Stop the Steal pays $3,500 to C Josi and Co.

December 21, 2016: Stop the Steal pays $1,500 to The Townsend Group

December 27, 2016: Stop the Steal pays $3,500 to Kristen [sic] Davis

December 28, 2016: Stop the Steal gives $94 to CRAG

December 29, 2016: Stop the Steal pays Jerry Steven Gray $4,000 for “fundraising expenses”

December 30, 2016: Stop the Steal pays 2,692 total to unnamed recipients

January 19, 2017: Stop the Steal pays $5,000 for fundraising expenses to Alejandro Vidal

February 8, 2017: Stop the Steal pays Kristen [sic] Davis $3,500 for “fundraising expenses”

February 15, 2017: Stop Steal pays Brad Boeck $862 for sales consultant consulting fee

Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)