When last we checked in on the MalwareTech (Marcus Hutchins) case, both FBI agents involved in his arrest had shown different kinds of unreliability on the stand and in their written assertions, and Hutchins’ defense had raised a slew of legal challenges that, together, showed the government stretching to use wiretapping and CFAA statutes to encompass writing code so as to include Hutchins in the charges. It looked like the magistrate in the case, Nancy Joseph, might start throwing out some of the government’s more expansive legal theories.

That is, it looked like the government’s ill-advised decision to prosecute Hutchins in the first place might be mercifully put out of its misery with some kind of dismissal.

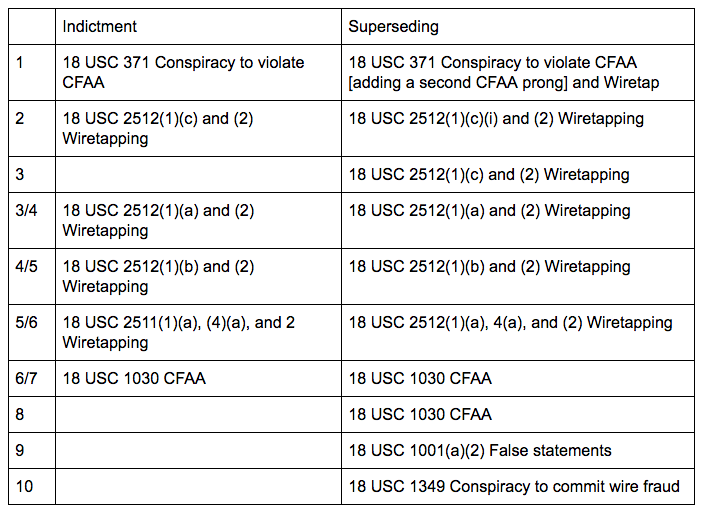

But the government, which refuses to cut its losses on its own prosecutorial misjudgments, just doubled down with a 10-count superseding indictment. Effectively, the superseding creates new counts, first of all, by charging Hutchins for stuff that 1) is outside a five year statute of limitations and 2) he did when he was a minor (that is, stuff that shouldn’t be legally charged at all), and then adding a wire fraud conspiracy and false statements charge to try to bypass all the defects in the original indictment. [See update below — I actually think what they’re doing is even crazier and more dangerous.]

The false statements charge is the best of all, because for it to be true a Nevada prosecutor would have to be named as Hutchins’ co-conspirator, because his representations in court last summer directly contradict the claims in this new indictment.

Wherein financial criminals VinnyK and Randy become bit players in criminal mastermind Marcus Hutchins’ drama

To understand how they’re doing this, first understand there are two criminals Hutchins is alleged to have had interactions with three-plus years ago:

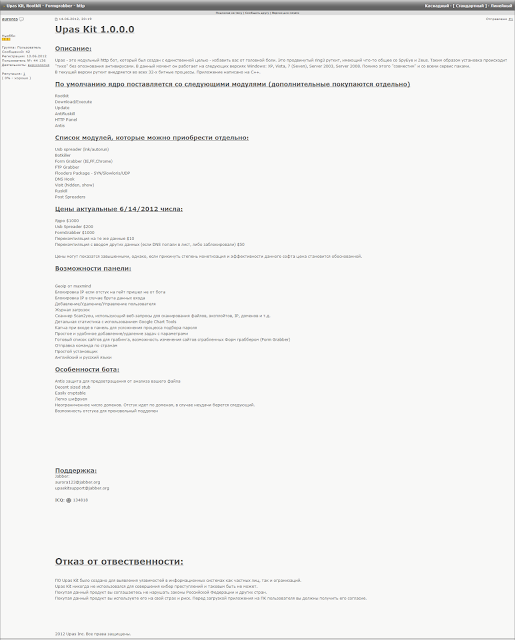

- VinnyK (Individual A), a guy who sold a UPAS kit on July 3, 2012, days after Hutchins turned 18, and then on June 11, 2015, sold Kronos, a piece of malware with no known US victims. Altogether VinnyK made $3,500 for the two sales of malware alleged in this indictment. When this whole thing started, the government charged Hutchins mostly if not entirely to coerce him to provide information on VinnyK (information which he said in a chat in the government’s possession he doesn’t have). He’s the guy they’re supposed to be after, but now they’re after Hutchins exclusively.

- “Randy” (Individual B), an actual criminal “involved in the various cyber-based criminal enterprises including the unauthorized access of point-of-sale systems and the unauthorized access of ATMs.” At some point, in an attempt to limit or avoid his own criminal exposure, Randy implicated Hutchins.

With this superseding indictment, the government has turned these two criminals into the bit players in a scheme in which Hutchins is now the targeted criminal.

Interestingly, unlike in the original indictment, VinnyK is not charged in this superseding indictment. I’m not sure what that means — whether the government has decided they like him now, they’ll never get him extradited and he won’t show up at DefCon because he’s learned Hutchins’ lesson, or maybe even they’ve gotten him to flip in a bid to avoid embarrassment with Hutchins. So there’s one guy the government admits is a criminal — Randy — and another guy they believed was a serious enough criminal they had to arrest the guy who saved the world from WannaCry to help find, VinnyK. Neither is charged in this indictment. Hutchins is.

Conspiracy to violate minors outside the statute of limitations

As I said, one way the government gets from 6 to 10 counts is by identifying a second piece of software — allegedly written by Hutchins — that VinnyK sold, so as to charge the same legally suspect crimes twice.

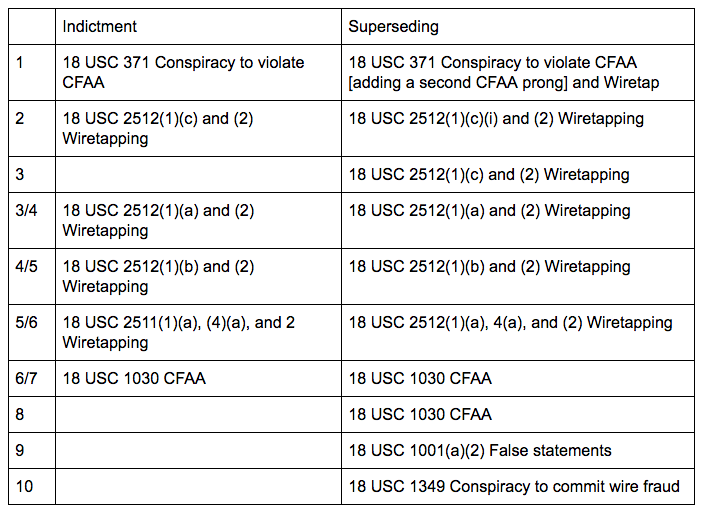

This is a comparison of the old versus new indictment.

As I understand it (though the indictment is damned vague on this point) the additional wiretapping and CFAA charges come from a second piece of software.

Here’s what that second alleged crime looks like:

a. Defendant MARCUS HUTCHINS developed UPAS Kit and provided it to [VinnyK], who was using alias “Aurora123” at the time.

b. On or about July 3, 2012, [VinnyK], sold and distributed UPAS Kit to an individual located in the Eastern District of Wisconsin in exchange for $1,500 in digital currency.

c. On or about July 20, 2012, [VinnyK], distributed an updated version of UPAS Kit to an individual in the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

First of all, notice how Hutchins’ activities in this second crime aren’t listed with any date? Wikipedia says Hutchins was born in June 1994 and I’ve confirmed that was when he was born. Which means either he coded UPAS Kit in a few weeks or less, or the actions he’s accused of here happened when he was a minor.

Now look at your calendar. July 2012 was 6 years ago, so outside a 5 year statute of limitations; for some reason the government didn’t even try to include the July 20, 2012 action when they first charged this last year. One way or another, the SOL has tolled on these actions.

The time periods for this new alleged crime, though, is listed as July 2014 to August 2014. Except all new actions listed in that time period are tied to Kronos, not UPAS. In other words, unless I’m missing something, the government has tried to confuse the jury by charging Kronos twice, all while introducing UPAS, which is both tolled and on which Hutchins’ alleged role occurred while he was a minor.

[See update below,]

Criminalizing malware research

The effort against Hutchins always threatened to criminalize malware research. But the government (perhaps in an effort to substantiate a second crime associated with Kronos) has gone one step further with this claim:

On or about December 23, 2014, defendant MARCUS HUTCHINS hacked control panels associated with Phase Bot, malware HUTCHINS perceived to be competing with Kronos. In a chat with [Randy], HUTCHINS stated, “well we found exploit (sic) [sic] in this panel just hacked all his customers and posted it on my blog sucks that these [] idiots who cant (sic) [sic] code make money off this :|” HUTCHINS then published an article on his Malwaretech blog titled “Phase Bot — Exploiting C&C Panel” describing the vulnerability.

The government doesn’t explain this (and I guarantee you they didn’t explain this to the grand jury — I mean they put the word “hacked” right there so it must be EVIL), but they’re claiming this article talking about how to thwart Phase Bot malware via vulnerabilities in its command and control module — that is, a post about how to defeat malware!!!! — is really a devious plot to undercut the competition.

Again, the original indictment was dangerous enough. But now the government is claiming that if you write about how to thwart malware, you might be doing it for criminal purposes.

Charging the other bad guys with wire fraud conspiracy

As a reminder, the charges in the original indictment (which remain largely intact here) were problematic because selling Kronos fit neither the definition of wiretapping nor CFAA (the latter because it doesn’t damage computers). In an apparent attempt to get out of that problem (though not the venue one, which best as I can tell remains a glaring problem here), they’ve added a conspiracy to commit wire fraud, arguing that Hutchins “knowingly conspired and agreed with [VinnyK] and others unknown to the Grand Jury, to devise and participate in a scheme to defraud and obtain money by means of false and fraudulent pretenses and transmit by wire in interstate and foreign commerce any writing, signs, and signals for the purpose of executing the scheme.”

I’ll let the lawyers explain whether this charge will hold up better than the wiretapping and CFAA ones. But at least as alleged, all VinnyK has ever done (even assuming Hutchins can be shown to have agreed with this) is to sell Kronos to an FBI agent in Wisconsin.

The only one in this entire indictment described as actually making money off using Kronos is Randy, the guy the US government isn’t prosecuting because he narced out Hutchins. Meaning the guy with whom Hutchins would most credibly be claimed to have conspired to commit wire fraud is the one guy not mentioned in the charge.

But for some reason the government decided the just thing to do when faced with these facts was charge only the guy who saved the world from WannaCry.

Charging false statements after both FBI agents have been shown to be unreliable

Which brings us, finally, to what is probably the point of this superseding indictment, the government’s effort to salvage their authority. They’ve charged Hutchins with lying to the FBI about knowing that his code was part of Kronos.

On August 2, 2017, the Federal Bureau of Investigation was conducting an investigation related to Kronos, which was a matter within the jurisdiction of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

On or about August 2, 2017, in the state of Eastern District of Wisconsin and elsewhere,

[Hutchins]

knowingly and willfully made a materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statement and represented in a matter within the jurisdiction of the Federal Bureau of Investigation when he stated in sum and substance that he did not know his computer code was part of Kronos until he reverse engineered the malware sometime in 2016, when in truth and fact, as HUTCHINS then knew, this statement was false because as early as November 2014, HUTCHINS made multiple statements to Individual B in which HUTCHINS acknowledged his role in developing Kronos and his partnership with Individual A.

Whoo boy.

First of all, as I’ve noted, one agent Hutchins allegedly lied to had repeatedly tweaked his Miranda form, without noting that she did that well after he signed the form. The other one appears to have claimed on the stand that he explained to Hutchins what he had been charged with, when the transcript of Hutchins’ interrogation shows the very same agent admitting he hadn’t explained that until an hour later.

So the government is planning on putting one or two FBI agents who have both made inaccurate statements — arguably even lied — to try to put Hutchins in a cage for lying. And they’re claiming that they were “conducting an investigation related to Kronos,” which is 1) what they didn’t tell Hutchins until over an hour after his interview started and 2) what they had already charged him for by the time of the interview.

Oh wait! It gets better. See how they describe that Hutchins lied in Wisconsin?

The interrogation happened in Las Vegas, which last I checked was not anywhere near Eastern District of Wisconsin. I mean, I’m sure there’s a way to finesse these things wit that “and elsewhere” language, but this indictment simply asserts that an interrogation room in the Las Vegas airport was in Milwaukee.

And there’s more!!!

On top of the fact that one or another agent who themselves have credibility problems would have to go on the stand to accuse Hutchins of lying, and on top of the fact that they say this thing that happened in Las Vegas didn’t stay in Las Vegas but was actually in Milwaukee, there’s the fact that AUSA Dan Cowhig, on August 4, 2017, in a bid to deny Hutchins bail, represented to a judge that,

In his interview following his arrest, Mr. Hutchins admitted that he was the author of the code that became the Kronos malware and admitted that he sold that code to another.

We don’t have the full transcript of Hutchins’ interrogation yet (parts released by the defense show him admitting to underlying code, which may be what this UPAS stuff is about, though denying Kronos itself). But for it to be true that Hutchins lied about knowing that “his computer code was part of Kronos until he reverse engineered the malware,” then Cowhig would have had to be lying last year.

So to sum up: the government’s bid to save face, on top of some jimmying with dates and using Randy to accuse Hutchins of something that Randy is far more guilty of, is to put two agents who have real credibility problems on the stand to argue that their colleague in Nevada, which apparently spends its summers in Wisconsin, lied last year when he claimed that Marcus admitted “he was the author of the code that became the Kronos malware.”

Update: It has been suggested those 2012 UPAS Kit actions got included because they are part of the conspiracy, which is how they get beyond tolling (though not Hutchins’ age). If the government is arguing that UPAS is the underlying code that Hutchins contributed to Kronos, then that might make sense. Except that then the false statements charge becomes even more ridiculous, because we know that Hutchins admitted to that bit.

Chartier: So you haven’t had any other involvement in any other pieces of malware that are out or have been out?

Hutchins: Only the form-grabber and the bot.

Chartier: Okay. So you did say the form-grabber for Kronos, then?

Hutchins: Not the form-grabber for Kronos. It was an earlier one released in about I’m gonna say 2014?

Also note, at least according to Hutchins’ jail call to his boss, GCHQ vetted this earlier activity and found it to be unproblematic.

Update: On fourth read (this indictment makes no sense), I think the new charges are not the 2012 sales, but a vague crime based on the marketing, but no sale, of malware in 2014. In other words, they’re accusing Hutchins of wiretapping and CFAA crimes because someone else posted a YouTube. Note, the YouTube in question has already been litigated, as the government is trying hard to get venue because of that — because YouTube is based in the US.

This is such an unbelievably dangerous argument; it’s a real testament to the sheer arrogance of this prosecution at this point, that they’ll stop at nothing to avoid the embarrassment of admitting how badly they fucked up.