The Disposition of Informants and Citizens

A lot of the commentary about Craig Whitlock’s Tuesday article on three alleged al Shabaab members rendered to the US focused on whether he accurately described this rendition–to a law enforcement proceeding and not, as happened under Bush, to a black site–or not.

A lot of the commentary about Craig Whitlock’s Tuesday article on three alleged al Shabaab members rendered to the US focused on whether he accurately described this rendition–to a law enforcement proceeding and not, as happened under Bush, to a black site–or not.

But I was more interested in whether the treatment of these three–Swedish citizens Ali Yasin Ahmed and Mohamed Yusuf and Madhi Hashi, a Somali who was raised in the UK, got citizenship there when he was 14, only to have it stripped shortly before he was detained–was indicative of the so-called disposition matrix first reported back in October then reportedly put on hold after Obama beat Mitt.

Consider the timing of both series of events. Hashi was stripped of his British citizenship in June. Shortly thereafter he disappeared from his home in Mogadishu. All three men were in detention in Djibouti by August. On October 18–five days before the first reporting on the disposition matrix–a grand jury returned a sealed indictment against the three. On November 14–conveniently after the election–the US government officially took custody of the men, thereby violating the intent of last year’s NDAA by bringing foreigners onto US soil. And on December 21, while most people were distracted by holidays and fiscal cliffs, the men were arraigned in the Eastern District (curiously, not the Southern District) of New York.

All of which took place as hints of this disposition matrix–an effort to map out contingencies for alleged extremists in a range of different positions–were reported.

“We had a disposition problem,” said a former U.S. counterterrorism official involved in developing the matrix.

The database is meant to map out contingencies, creating an operational menu that spells out each agency’s role in case a suspect surfaces in an unexpected spot. “If he’s in Saudi Arabia, pick up with the Saudis,” the former official said. “If traveling overseas to al-Shabaab [in Somalia] we can pick him up by ship. If in Yemen, kill or have the Yemenis pick him up.”

In other words, the rendition of these three men–in addition to whatever else it was, and I think the case that it was a legitimate use of US law enforcement is thus far weak, though still preferable to a drone strike against the three–seems like a test drive of this disposition process.

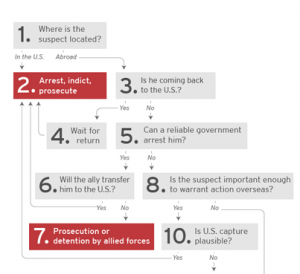

Which is why I find it so interesting that two wired up commentators like Daniel Byman and Benjamin Wittes have rolled out what they represent to be the flow chart–they even call it the disposition matrix–the Obama Administration uses if it believes you’re a terrorist.

Because that flow chart is not just incomplete, but factually wrong on several points.

Take step 11, which asks whether a person overseas is an operational leader or not.

Propagandists, to some degree, are also protected under U.S. law. Glorifying jihad and saying that Americans fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, or even living ordinary lives stateside, deserve death, is not in itself a crime. So even Anwar al-Awlaki, who inspired Americans and Western Muslims in general to take up jihad, was not aggressively targeted until he was linked to attacks on U.S. airlines and aviation targets in the United Kingdom — thus going from “propagandist” to “operator.” Non-operational figures abroad — however dangerous — will tend to be tolerated to the extent they cannot be captured.

The claim that Awlaki was “not aggressively targeted until he was linked to attacks on U.S. airlines” is false. JSOC targeted him the day before the Intelligence Community first started tying him to operations.

But the case of these three men also illustrates the grey areas of this matrix. Presumably, their path would go:

1. Where is the suspect located? Abroad.

3. Is he coming [back to] the US? No. [As far as we know, none were ever in the US]

5. Can a reliable government arrest him? Yes.

6. Will the ally transfer him to the US? Yes.

2. Arrest, indict, prosecute.

As a threshold matter, what happened before this matrix–at least for Hashi–is that the suspect was returning to the UK when his “disposition” process started. As far back as April 2009, MI5 was blackmailing Hashi and his friends to turn informants.

Five Muslim community workers have accused MI5 of waging a campaign of blackmail and harassment in an attempt to recruit them as informants.

The men claim they were given a choice of working for the Security Service or face detention and harassment in the UK and overseas.

[snip]

Madhi Hashi, a 19-year-old care worker from Camden, claims he was held for 16 hours in a cell in Djibouti airport on the orders of MI5. He alleges that when he was returned to the UK on 9 April this year he was met by an MI5 agent who told him his terror suspect status would remain until he agreed to work for the Security Service. He alleges that he was to be given the job of informing on his friends by encouraging them to talk about jihad.

After that he returned to Somalia and married. In June, he was stripped of his citizenship, and then disappeared even before he could have appealed the decision.

In June 2012, a letter delivered to Hashi’s family home in London informed him that the home secretary Theresa May had decided to strip him of his British citizenship, claiming he had been ‘involved in Islamist extremism’.

The letter added that he had four weeks to appeal, but he disappeared before he was able to act.

A man later contacted his family in Somalia claiming he had been held alongside Hashi in a Djibouti jail.

Mahdi’s father Mohamed Hashi told the Bureau: ‘He said [Hashi] was fingerprinted and his DNA was taken, and they found out that he was a British citizen and contacted the British consulate – but the British said sorry, we took his citizenship away from him and we can’t help him.’

And somewhere along the line, Hashi got transferred from Somalia (does that count as a reliable government?) to Djibouti, which has largely become an appendix to the US base there.

Then Hashi sat in Djibouti for up to four months, undergoing who knows what kind of interrogations and under whose authorities. That grey zone interrogation curiously doesn’t show up on Byman and Wittes’ matrix, though such extended interrogations leading to US prosecutions are becoming more and more frequent.

Finally, note the US focus of the matrix: US presence, “return to” US, US prosecution.

In this case, all for crimes connected with a group with which we’re not at war (though we have declared it a terrorist organization). (In his piece on renditions, Whitlock correctly points to Ahmed Warsame as a direct precedent, but in that case Warsame was conspiring with AQAP, against which we are at war.)

The indictments, too, are interesting. Not only do both the October indictment and the November superseding indictment obscure the timeline involved by stating only the alleged crimes occurred from 2008 (before the Brits started harassing Hashi) until 2012 (when he was detained). But the superseding indictment adds the weaker charge of conspiracy to commit material support, suggesting some concern about the strength of the material support charge itself. In press releases but not the indictments, the government claims the men were training at a suicide bomber camp, but even after having Djibouti detain Hashi for 5 months and then detaining him secretly here for a month, they apparently don’t tie any charge to that alleged suicide bomb training.

Given the timing of all this, I wonder whether the celebrated British-recruited Saudi-run UndieBomb infiltrator was once buddies with Hashi, and they rolled Hashi up in the aftermath of that plot?

In any case, the most likely thing that will come out of this “disposition” is that, having refused to become an informant, Hashi will spend the rest of his life living in US taxpayer funded prisions, without the government actually accusing him of plotting against the US.

Maybe he did, in which case the disposition matrix worked. But that’s why we used to demand transparency (and no five month period without due process) for this kind of thing

In short, this rendition might be an improvement over the drone strikes. But if it is, the government has not made the case it is.