Update: The day I wrote this post, Judge Scarsi denied Abbe Lowell’s motion to supplement the record on procedural grounds.

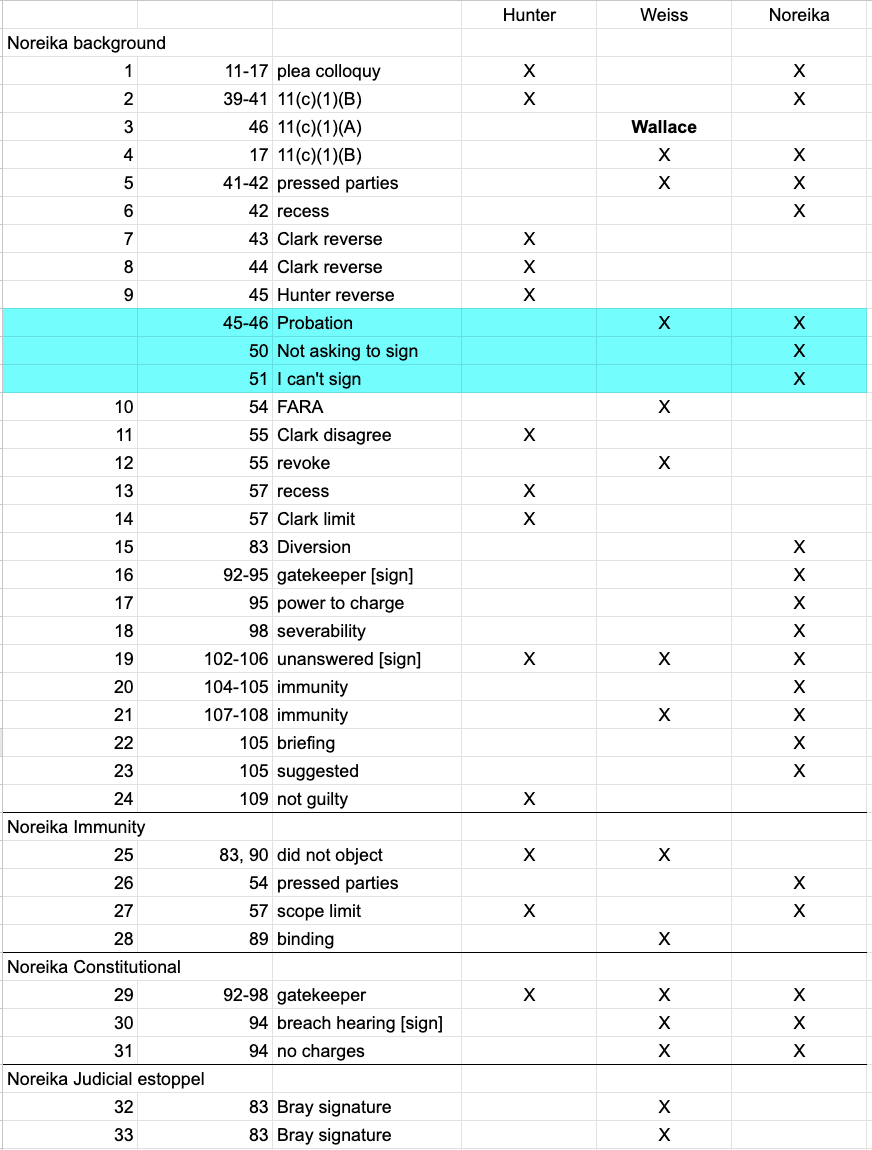

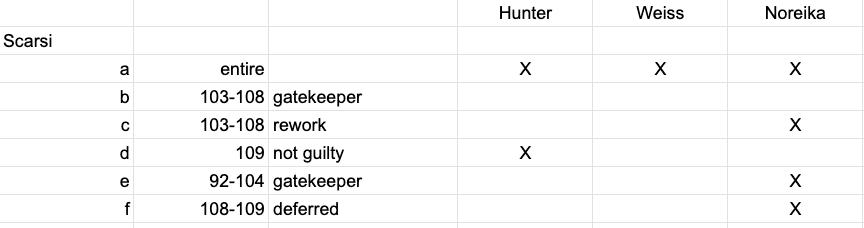

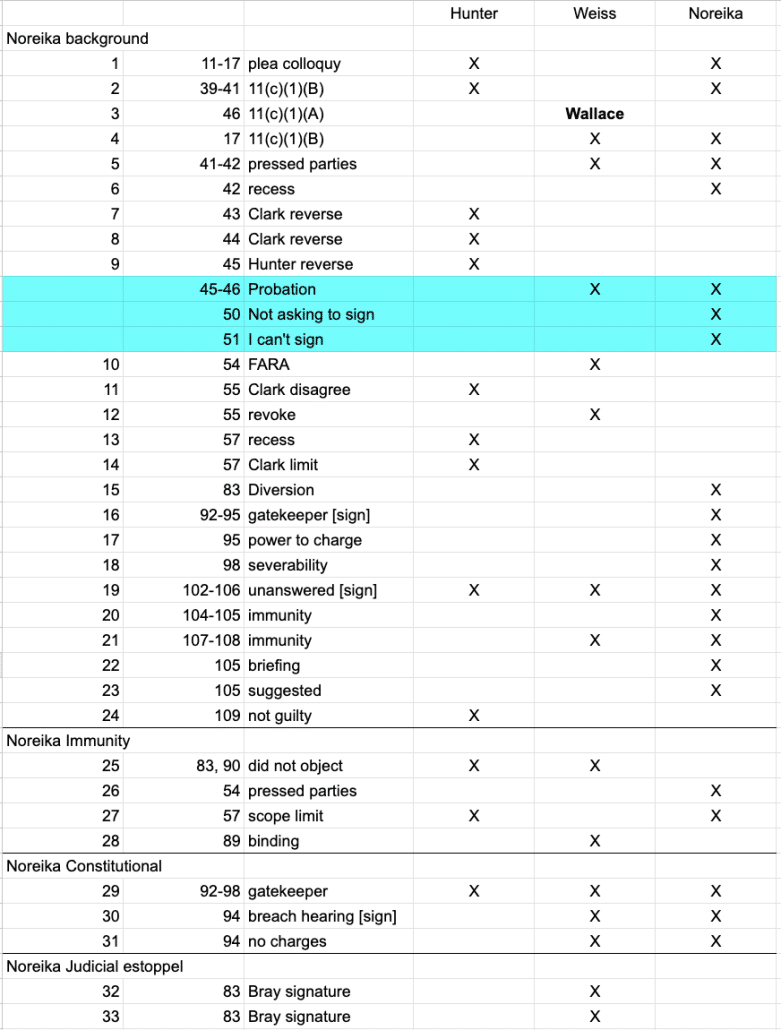

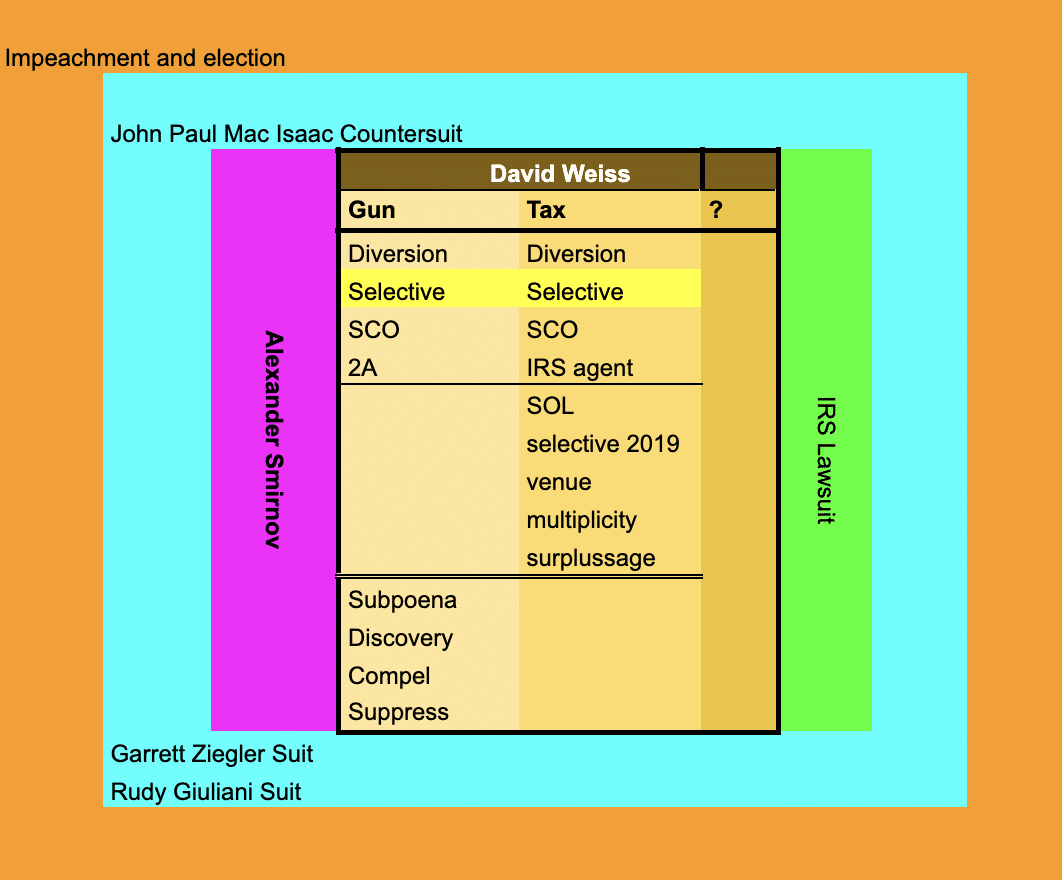

Aside from his opinion on the diversion agreement — which gets weirder and weirder the more I look at it — Judge Mark Scarsi’s denials of the seven other Hunter Biden motions to dismiss were totally in line with precedent and my own expectations of what Scarsi would do.

To each of what I called the technical motions to dismiss, Judge Scarsi left it to the jury to decide. Scarsi relied on prior rulings on past Special Counsel appointments to deem David Weiss’ appointment legal. And for the Selective and Vindictive claim and the Egregious Misconduct claim, Scarsi ruled that the standard for dismissal is extremely high and Hunter Biden didn’t reach it.

Ordinarily, no judge would be reversed by ruling in such a fashion. All of his decisions are the easy out based on precedent — the cautious approach.

But it’s on the last two — the ones where all Judge Scarsi had to say was that the standard was super high — where he may have provided surface area for attack on appeal.

This post got overly long so here’s a map.

First, I lay out how Judge Scarsi claims to be demanding a laudably rigorous standard of evidence and procedure. Then, I show how in one of his correct fact checks of Abbe Lowell, Scarsi ends up providing more focus on the threats David Weiss faced, while debunking that Weiss testified they were death threats; that’s a topic on which Leo Wise provided wildly misleading testimony. I next look at how Scarsi claims to adopt a standard on the influence the IRS leaks had throughout the period of the prosecution, but ultimately only reviews whether those leaks had an effect on the grand jury (the standard Weiss wanted that Scarsi said he did nto adopt). Then I lay out two 9th Circuit opinions via which Scarsi accuses Lowell’s timeline argument to be a post hoc argument. Finally, I show how even while Scarsi fact checks some of Lowell’s claims, elsewhere he arbitrarily changes the timeline or ignores key parts of it. This last bit is the most important part, though it builds on the earlier parts, so skip ahead and read that. Finally, I note that Abbe Lowell may have erred by failing to put details about the Alexander Smirnov before Judge Scarsi.

A laudably hard grader

Ironically, that surface area arises, in significant part, from Scarsi’s attempted attentiveness, which I hailed a few weeks ago when he offered David Weiss a chance to respond to concerns that he was arbitraging (my word) his SCO appointment.

Scarsi’s attentiveness carries over to this opinion.

Once upon a time I was known as a hard grader and so I genuinely appreciate Scarsi’s attention to detail. I think he raises a number of good points about Abbe Lowell’s failure to meet Scarsi’s insistence on procedural rigor and factuality.

On the first part, for example, many reporters had claimed that Scarsi scolded Lowell at the motions hearing that he had no evidence (I’m still working on getting a transcript from Scarsi’s court reporter).

As this opinion makes clear, that was, first and foremost, a comment on the fact that Lowell had not submitted a declaration to attest to the authenticity of his citations.

As the Court stated at the hearing, Defendant filed his motion without any evidence. The motion is remarkable in that it fails to include a single declaration, exhibit, or request for judicial notice. Instead, Defendant cites portions of various Internet news sources, social media posts, and legal blogs. These citations, however, are not evidence. To that end, the Court may deny the motion without further discussion. See Fed. R. Crim. P. 47(b) (allowing evidentiary support for motions by accompanying affidavit); see also C.D. Cal. R. 7-5(b) (requiring “[t]he evidence upon which the moving party will rely in support of the motion” to be filed with the moving papers); C.D. Cal. Crim. R. 57-1 (applying local civil rules by analogy); cf. C.D. Cal. Crim. R. 12-1.1 (requiring a declaration to accompany a motion to suppress).

In at least one place, Scarsi even makes the same criticism of prosecutors, for not submitting the tolling agreements on which they relied with such a declaration.

This is a procedural comment, not an evidentiary one. It is a totally fair comment from a judge who, parties before him should understand, would insist on procedural regularity. He’s a hard grader.

That said, Scarsi’s claim that Lowell submitted no evidence is factually incorrect on one very significant point: In Lowell’s selective prosecution motion, he incorporated the declaration and exhibits included with the diversion agreement motion, which is cited several more times.

3 The extensive back-and-forth negotiation between the U.S. Attorney’s Office and Mr. Biden’s counsel regarding the prosecution’s decision to resolve all investigations of him is discussed in the declaration of Christopher Clark filed currently with Mr. Biden’s Motion to Dismiss for Immunity Conferred by His Diversion Agreement. (“Clark Decl.”)

So the record of the plea negotiations — an utterly central part of these disputes — did come in under the procedural standards Scarsi justifiably demanded. Even if you adopt Scarsi’s procedural demands, those records of how the plea deal happened are evidence before Scarsi.

Given Scarsi’s procedural complaint, though, it’s not entirely clear what the procedural status of this complaint is. As noted, Lowell did submit a declaration attesting to the authenticity of these documents before Scarsi unexpectedly ruled 16 days earlier than he said he would. Scarsi has not rejected it.

In any case, Scarsi described that he dug up and reviewed “all the cited Internet materials” Lowell cited himself and ruled based on that.

In light of the gravity of the issues raised by Defendant’s motion, however, the Court has taken on the task of reviewing all the cited Internet materials so that the Court can decide the motion without unduly prejudicing Defendant due to his procedural error.21

Having done that, though, Scarsi accuses Lowell of misrepresenting his cited sources.

21 However, Defendant mischaracterizes the content of several cited sources. The Court notes discrepancies where appropriate.

He’s not wrong! And honestly, this is the kind of fact checking I appreciate from Scarsi.

It’s the same ethic that led me to check Judge Scarsi’s claims about an exhibit that he misrepresented in his diversion agreement opinion, claiming that “the parties changed” the diversion agreement when in fact the exhibit said, “The parties and Probation have agreed to revisions to the diversion agreement,” arguably recording the agreement from Probation that, under Scarsi’s ruling, would trigger an obligation that prosecutors adhere to the immunity agreement he says is contractually binding.

It’s the same ethic that led me to check Judge Scarsi’s citation of Klamath v Patterson, only to discover he had truncated his citation, leaving out the bolded language below that would suggest this agreement is ambiguous and therefore should be interpreted in Hunter Biden’s favor.

The fact that the parties dispute a contract’s meaning does not establish that the contract is ambiguous; it is only ambiguous if reasonable people could find its terms susceptible to more than one interpretation. [my emphasis]

I genuinely do appreciate the fact that Scarsi tests the claims people make before him.

I do too.

The threats that at least five witnesses have described were real and likely incited by the IRS agents but may not have been death threats

One fact check of note that Scarsi raises, for example, pertains to Lowell’s citation of Politico’s coverage of David Weiss’ testimony, including the Special Counsel’s admission that he was concerned for the safety of his family. Scarsi notes that Politico doesn’t report, as Lowell claimed, that “Mr. Weiss reported he and others in his office faced death threats and feared for the ‘safety’ of his team and family.”

In a closed-door interview with Judicial Committee investigators in November 2023, Mr. Weiss reportedly acknowledged that “people working on the case have faced significant threats and harassment, and that family members of people in his office have been doxed.” Betsy Woodruff Swan, What Hunter Biden’s prosecutor told Congress: Takeaways from closed-door testimony of David Weiss, Politico (Nov. 10, 2023, 2:05 p.m.), https://www.politico.com/news/2023/11/10/ hunter-biden-special-counsel-takeaways-00126639.34

34 Although Mr. Weiss reportedly admitted “he is . . . concerned for his family’s safety,” Woodruff Swan, supra, this outlet did not report that Mr. Weiss “and others in his office faced death threats.” (Selective Prosecution Mot. 7.)

Scarsi is right. Those words, “death threats,” are not in the story. “Significant threats,” but not “death threats.”

Nor is it in Weiss’ still unreleased transcript, in which Weiss twice used the word “intimidated” when decrying such threats.

It’s not in Assistant Special Agent in Charge Ryeshia Holley’s testimony, where she described precautions taken for at least one of her FBI agents and for prosecutor Lesley Wolf after they were stalked and received comments of “a concerning nature.” It’s not in Lesley Wolf’s own testimony; rather, she described delaying her departure from DOJ because she believed she’d be safer if she remained a DOJ employee. Wolf also explained how her family had, “changed the way we do some things at home because of” the threats and stalking. A specific description of death threats is likewise not in the testimony of Los Angeles US Attorney Martin Estrada — effectively, a local colleague of Judge Scarsi — when he described working with the US Marshals because of “an uptick [of threats and hate mail] when the news came out in the spring regarding the Hunter Biden investigation,” including dozens of hate messages, some using the N-word and others using “certain derogatory terms reserved for Latinos.”

It’s not even in Ken Dilanian’s report (which Lowell did not cite), based off this congressional testimony as well independent reporting, describing how prosecutors and FBI agents have been the target of threats because they weren’t tough enough on Hunter Biden.

Prosecutors and FBI agents involved in the Hunter Biden investigation have been the targets of threats and harassment by people who think they haven’t been tough enough on the president’s son, according to government officials and congressional testimony obtained exclusively by NBC News.

It’s part of a dramatic uptick in threats against FBI agents that has coincided with attacks on the FBI and the Justice Department by congressional Republicans and former President Donald Trump, who have accused both agencies of participating in a conspiracy to subvert justice amid two federal indictments of Trump.

The threats have prompted the FBI to create a stand-alone unit to investigate and mitigate them, according to a previously unreleased transcript of congressional testimony.

None of these sources — and except for Dilanian, who has proven unreliable in the past, I’m working from official sources — mention death threats. Whether they mention influence from the IRS agents’ public campaign is a different issue.

Dilanian insinuated there was a tie between the threats against Wolf and the claims by Gary Shapley and Joseph Ziegler that Wolf “ma[de] decisions that appeared favorable to Biden.” US Attorney Estrada — Scarsi’s quasi colleague in Los Angeles — suggested a temporal tie, but didn’t mention the IRS agents.

As I’ve noted, though, Special Agent in Charge Thomas Sobocinski was more direct. When asked what he meant when he said that he and David Weiss had “both acknowledged that [Gary Shapley’s public comments were] there and that it would have had[,] it had an impact on our case,” Sobocinski described the effect to be the stalking of not just members of the investigative team, but also their family members.

None of this documented testimony described death threats. Scarsi is right on that point! The near unanimity that the prosecution team faced doxing and in some cases threats doesn’t describe the kind of threats, though US Marshals had to get involved on both coasts and some sources attribute those threats to the IRS agents, in Sobocinski’s case, explicitly.

That said, most of this documented testimony is unavailable to Hunter Biden’s lawyers, because Jim Jordan won’t release it, and because instead of sharing it, David Weiss sat in Scarsi’s own courtroom watching Leo Wise make claims about the impact of the IRS agents’ leaks that may be technically true as far as Wise’s experience (it’s not Leo Wise’s family being followed, presumably), but hides the impact on the prosecution team before Wise joined the team — the impact that Sobocinski described to Congress.

So I admire Judge Mark Scarsi for holding Abbe Lowell to the documentary record. As a former hard grader, I think such accuracy is important.

But Scarsi’s complaints about Lowell’s misrepresentation of the reported record about these threats also serve to highlight what David Weiss (and Jim Jordan) are withholding from Hunter Biden and his attorney, even while misleading Scarsi about it.

Incidentally but importantly, because Abbe Lowell relied on a NYPost story for the Estrada citation, he relied on a source that presented only part of what the LA US Attorney said about his team’s analysis of why they recommended against partnering with Weiss on a Hunter Biden prosecution, the part focusing on how resource-strapped he was and how there were many far more urgent crimes to prosecute in LA.

Estrada also said there was an evidentiary part of the discussion.

We only prosecute cases where we believe a Federal offense has been committed and where we believe there will be sufficient admissible evidence to prove a case beyond a reasonable doubt to an unbiased trier of fact.

But of course, that (plus the three underlying reports recommending against prosecution) are another thing Weiss has withheld.

Judge Scarsi adopts — then abandons — a standard on IRS leaks

Which leads me to one of three things that — on top of Scarsi’s miscitation of that exhibit recording involvement from probation in revising the diversion agreement and his truncation of a relevant precedent to give it the opposite meaning — I think may provide more surface area for attack on appeal.

It pertains to Judge Scarsi’s ruling on Hunter’s outrageous conduct motion, in which Abbe Lowell argued that the extended media campaign from the IRS agents had resulted in a grave due process violation.

Scarsi makes a big show of adopting a different standard than the one David Weiss — the guy who reportedly sat in Scarsi’s courtroom and saw Leo Wise make a claim that was not true as it applied to himself — advocated: that the charges themselves “result from” the outrageous government conduct at issue.

48 The Government advances a rule that “the defendant must show that the charges resulted from” the outrageous government conduct to show a due process violation. (Outrageous Conduct Opp’n 4–9.) Though the Government’s presentation is persuasive, the Court stops short of adopting that rule. It is true that courts often consider the doctrine in contexts where the defendant asserts the offending government conduct played a causal role in the commission, charge, or conviction of a crime. (Id. at 7–8 (summarizing Russell, 411 U.S. 423; Pedrin, 797 F.3d 792; United States v. Combs, 827 F.3d 790 (8th Cir. 2016); Stenberg, 803 F.2d 422; United States v. Garza-Juarez, 992 F.2d 896 (9th Cir. 1993); and Marshank, 777 F. Supp. 1507).) And the Government’s proposed rule aligns with the proposition that “the outrageous conduct defense is generally unavailable” where the crime is in progress or completed before the government gets involved. Stenberg, 803 F.2d at 429. But the Ninth Circuit teaches that there is no one-size-fits-all rule for application for the doctrine, see Black, 733 F.3d at 302 (“There is no bright line dictating when law enforcement conduct crosses the line between acceptable and outrageous, so every case must be resolved on its own particular facts.” (internal quotation marks omitted)), and nothing in the Supreme Court’s acknowledgment of the doctrine mandates that the offending misconduct play some causal role in the commission of the crime or the levying of charges, see Russell, 411 U.S. at 431–32. The Court takes the Second Circuit’s cue and leaves the door open to challenges based on “strategic leaks of grand jury evidence by law enforcement.” Walters, 910 F.3d at 28. [my emphasis]

Elsewhere, addressing a slightly different argument from Lowell, Scarsi describes that the standard is “substantially influenc[ing] the grand jury’s decision to indict, or if there is grave doubt the decision to indict was free from the substantial influence of such violations.” [my emphasis]

Exercise of supervisory authority to dismiss an indictment for wrongful disclosure of grand jury information is not appropriate unless the defendant can show prejudice. Walters, 910 F.3d at 22–23 (citing Bank of N.S., 487 U.S. at 254–55). In other words, “dismissal of the indictment is appropriate only if it is established that the violation substantially influenced the grand jury’s decision to indict, or if there is grave doubt that the decision to indict was free from the substantial influence of such violations.” Bank of N.S., 487 U.S. at 256 (internal quotation marks omitted).

Scarsi claims to adopt a standard in which egregious government misconduct could have an influence elsewhere, besides just causing the charges against the defendant, as Weiss wants the standard to be. So Scarsi says the standard doesn’t require a direct influece on the grand jury.

Then he abandons that standard.

In his ruling, Scarsi ultimately adopts Weiss’ standard of causing a prejudicial effect on the grand jury’s decision.

Defendant offers no facts to suggest that the information Shapley and Ziegler shared publicly had any prejudicial effect on the grand jury’s decision to return an indictment. That Shapley and Ziegler’s public statements brought notoriety to Defendant’s case is not enough to show prejudice.50

50 As noted previously, Defendant himself brought notoriety to his conduct though the publication of a memoir. [my emphasis]

In the same breath, he offers up a gratuitous representation that Hunter’s complaint was about notoriety and not, along with the threats to prosecutors’ family members, the ability to get a fair trial.

Judge Scarsi claims he was not going to exclude the impact that leaks might have earlier in the process; he’s referencing a case in which the offending federal official leaked documents for 16 months. But ultimately, he adopts Weiss’ focus on the actual grand jury decision to indict.

Now, as I suggested above, with regards to the evidence in front of Scarsi, his opinion is still totally sound, because Weiss is withholding precisely the proof of influence that Leo Wise claims doesn’t exist. But when Sobocinski’s testimony becomes public — whether via Hunter Biden’s IRS lawsuit, a change in Congress, or discovery challenges launched by Hunter himself — Scarsi’s adoption (then abandonment) of the possibility that strategic leaks could be basis for dismissal could become important. The standard is, as Scarsi says, still very very high. But the evidence in question attributes the stalking and threats against investigative personnel, including Weiss himself, to Shapley’s leaks. The IRS leaks caused the threats which immediately preceded Weiss reneging on the plea deal.

Get Me Roger Stone

As noted, in his discussion of the IRS leaks, Scarsi includes a gratuitous swipe that Hunter Biden’s memoir created notoriety. In doing so, Scarsi probably has adopted the prosecution’s continued misrepresentation of what the memoir does and does not do.

As to the crimes alleged in both the tax indictment and gun indictment, Hunter’s memoir couldn’t have brought notoriety to his conduct from the memoir. As Lowell correctly pointed out, Hunter’s memoir doesn’t describe failing to pay his taxes or buying a gun.

Hunter’s notoriety substantially comes from release of his private files by the same Donald Trump attorney who solicited dirt about Hunter from known Russian spies. Rudy Giuliani’s leaks are before Scarsi in several forms, in articles describing Trump’s politicization of them.

And the IRS agent claims — virtually all of which have been debunked or explained — were different in kind, because they were the kind of claims that could, and did, gin up threats against investigators rather than just Hunter himself. The IRS agents targeted David Weiss and Lesley Wolf. Hunter’s memoir didn’t do that.

Finally particularly in the context of the discussion about the IRS agent, Scarsi seems to adopt this swipe from prosecutors. But I think it overstates what the memoir shows and certainly overstates what is before Scarsi. The two longest quotes from the memoir in the indictment focus on the riff raff being a wealthy junkie attracts. For example, the passages of the memoir before Scarsi refer to strippers but does not say Hunter slept with them.

thieves, junkies, petty dealers, over-the-hill strippers, con artists, and assorted hangers-on,

[snip]

my merry band of crooks, creeps, and outcasts

[snip]

An ant trail of dealers and their sidekicks rolled in and out,

[snip]

Their stripper girlfriends invited their girlfriends, who invited their boyfriends.

This is important because both Shapley and Ziegler focused on prostitutes in their testimony to Congress (indeed, it’s how Ziegler predicated his side of the investigation). Worse still, Ziegler falsely called Lunden Roberts (an exotic dancer when Hunter met her) — who, as the recipient of the best-documented improper write-off from Hunter, may be a witness at trial — a prostitute before he corrected himself. So the IRS agents, not the memoir, pushed one aspect highlighted in the indictment that is not in the book: the sex workers. Remember: the indictment itself conflates women with prostitutes (and appears to ignore a male who tried to insinuate himself into Hunter’s life as an assistant); the same conflation Ziegler engaged in appears in the indictment.

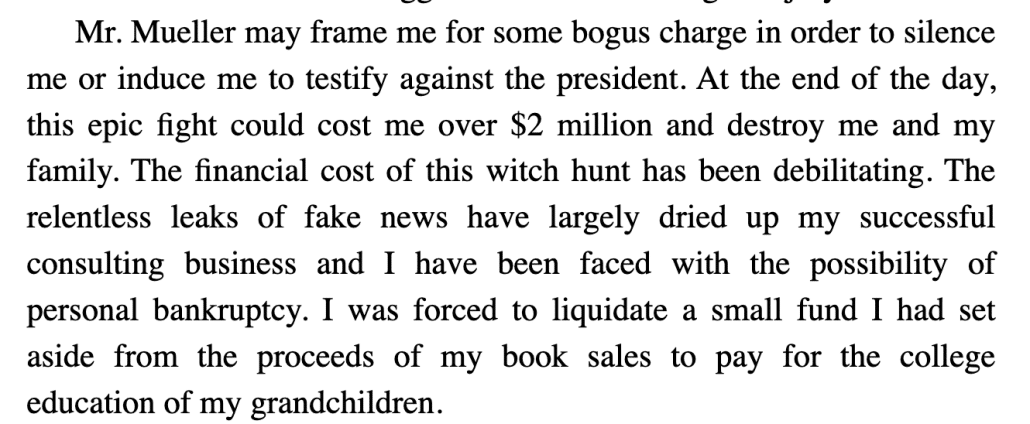

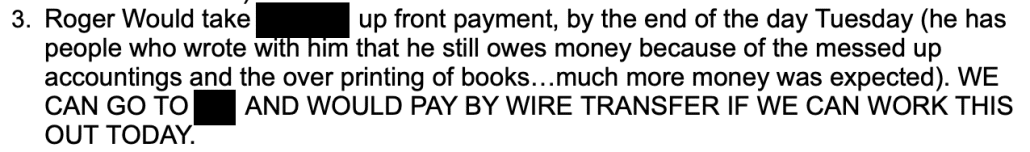

Which brings me back to Weiss’ false claims about memoirs and Roger Stone.

As a reminder, the selective comparator is not a huge part of Hunter Biden’s argument. He focused on the way a political campaign that led to stalking and threats against prosecutors led David Weiss to abandon a plea deal.

But Stone is in there. And in suggesting that Stone is not a fair comparator, Judge Scarsi punts on a number of things. For example, he admits that DOJ accused Stone, via civil complaint, of defrauding the United States.

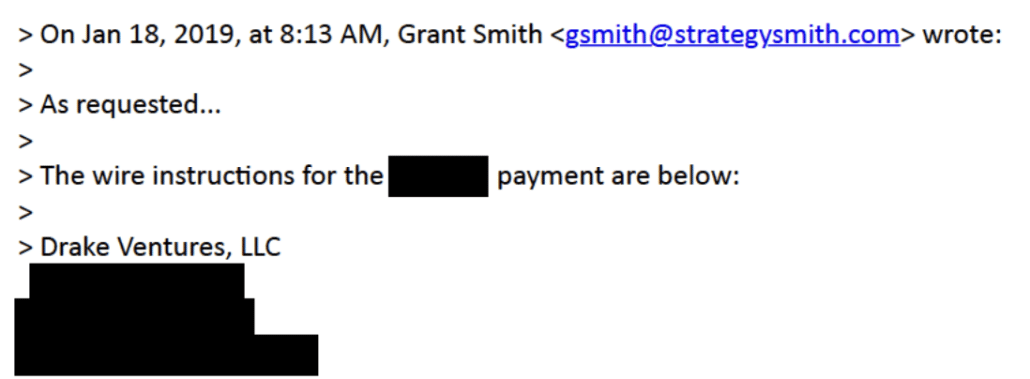

The Stones intended to defraud the United States by maintaining their assets in Drake Ventures’ accounts, which they completely controlled, and using these assets to purchase the Stone Residence in the name of the Bertran Trust.

But Scarsi seems to dismiss the intent involved in creating alter egos to hide money from the IRS because the civil resolution of the complaint led to voluntary dismissal of the fraud claim.

Nothing in the record of the civil cases, let alone in the circumstances of the “countless others” the Government declines to prosecute, (Selective Prosecution Mot. 19), provides an inference that these individuals are similarly situated to Defendant with regard to indicia of criminal intent. Obviously, Stone and Shaughnessy were civil cases; intent was not a material element of the nonpayment counts at issue. See generally Compl., United States v. Stone, 0:21-cv60825-RAR (S.D. Fla. April 16, 2021), ECF No. 1; 37

37 Intent was an element to a claim for fraudulent transfer the United States brought against the Stones, which the United States eventually dismissed voluntarily. Joint Mot. for Entry of Consent J. 1, United States v. Stone, 0:21-cv-60825-RAR (S.D. Fla. July 15, 2022), ECF No. 63.

But that’s part of the point! IRS used the threat of fraud and evasion charges to get the bills paid, and they dismissed what could have been a separate criminal charge — one they allege was done to evade taxes — once they got their bills paid. Hunter didn’t get that chance, in part because he paid his taxes two years before the charges filed against him.

Stone allegedly evaded taxes for two tax years, not one, and unlike Hunter, had not paid when the legal proceeding was filed against him.

And Scarsi doesn’t address the full extent of Lowell’s rebuttal to Weiss’ attempt to minimize Stone; he doesn’t note they’ve been caught in a false claim.

But adopting Defendant’s position would ignore the numerous meaningful allegations about Defendant’s criminal intent that are not necessarily shared by other taxpayers who do not timely pay income tax, including the Shaughnessys and Stones. (See Selective Prosecution Opp’n 2–4

(reviewing allegations).) Without a clear showing that the evidence going to criminal intent “was as strong or stronger than that against the defendant” in the cases of the Shaughnessys, the Stones, and other comparators, the Court declines to infer discriminatory effect. United States v. Smith, 231 F.3d 800, 810 (11th Cir. 2000).38

For example, Scarsi doesn’t mention, at all, that the other Stone crimes invoked in the DOJ complaint against Stone posed real rather than hypothetical danger to a witness and a judge and were invoked as his motive in the complaint, not even though that was part of the rebuttal that Weiss attempted to make. He doesn’t mention that the complaint against Stone alleges that Stone used his Drake account to pay associates and their relatives, one of the allegations included in the Hunter indictment, nor that it describes how instead of paying taxes the Stone’s enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, again repeating allegations in the Hunter indictment.

32. The Stones used Drake Ventures to pay Roger Stone’s associates, their relatives, and other entities without providing the required Forms 1099-MISC (Miscellaneous Income) or

W-2s (Wage and Tax Statement).

[snip]

[T]he Stones’ use of Drake Ventures to hold their funds allowed them to shield their personal

income from enforced collection and fund a lavish lifestyle despite owing nearly $2 million in

unpaid taxes, interest and penalties.

Scarsi does recognize, in passing, to how Weiss falsely claimed that Stone hadn’t written a memoir when it was actually more closely tied to the complaint than Hunter’s.

38 In his reply, Defendant proffers that Mr. Stone “wrote a memoir about his criminal actions,” as Defendant is alleged to have done. (Selective Prosecution Reply 6 (emphasis removed).) That memoir is not before the Court, and its value as evidence in a putative criminal tax evasion case against Mr. Stone is unestablished.

Now, Scarsi is absolutely right on this point as well: Abbe Lowell should have ponied up for Stone’s reissued Memoir so Scarsi could read it. But some of the evidence of the tie is before him.

Judge Scarsi might include Lowell’s link to my post among those that were not part of the record when he drafted this opinion — what he described as Lowell’s lack of evidence. But it was included among those for which Lowell submitted a declaration before Scarsi docketed his opinion (on which filing Scarsi has thus far taken no action). If Scarsi read all of Lowell’s sources as he claimed, it would be before him. (Welcome to my humble blog, Judge Scarsi!)

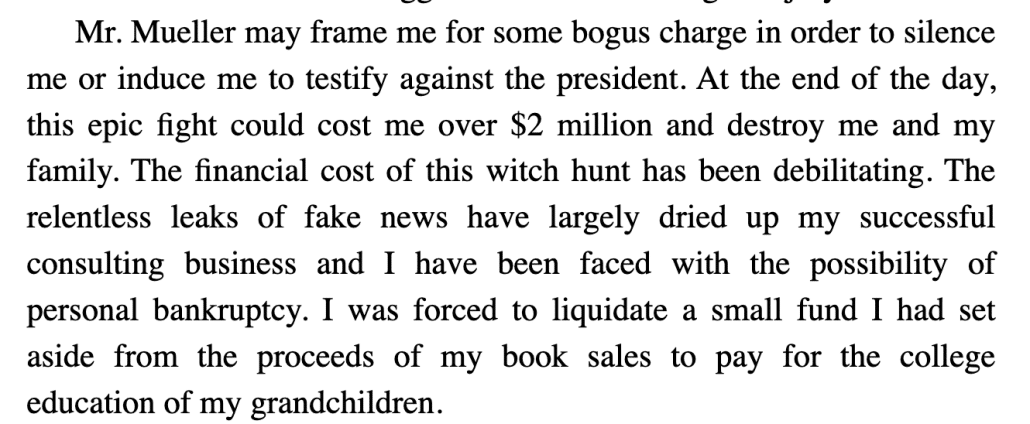

While my post did not link the memoir, it included a paragraph by paragraph description of the introduction that violated the gag order. I described how Stone, “Complains about his financial plight,” in this paragraph, which, like the tax complaint, ties Stone’s decision to stop paying taxes to the Mueller investigation:

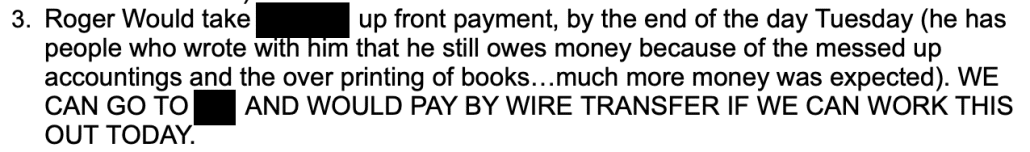

Furthermore, my post did include a link to this filing, providing much of the correspondence regarding the reissue of the memoir. It includes, for example, Stone’s demand for an immediate wire payment because he owed others — people who worked on the book, but also likely potential witnesses in the Mueller investigation (for example, Kristin Davis, who was subpoenaed in that investigation and the January 6 investigation, was heavily involved in promotion of the book).

Stone was describing doing prospectively what the Hunter indictment alleges prospectively, payoffs to associates and their family members.

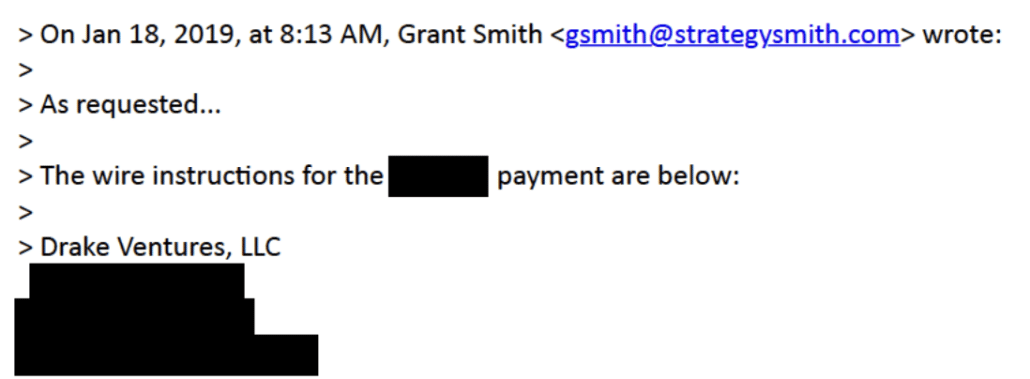

It also shows that Stone was paid, once in December 2018 and once in January 2019, to the Drake Ventures account that was used — per DOJ’s complaint — with the intent of defrauding the United States.

In unredacted form, those emails would provide one of just two of the kinds of information for which the tax indictment — as distinct from the gun indictment, which relies on it much more directly (though Weiss got his evidence wrong, again, and so misstates its value) — uses the memoir: To show income that could have gone to paying taxes.

158. In 2020, prior to when the Defendant filed the 2019 Form 1040, the Defendant’s agent received multiple payments from the publisher of his memoir and then transferred the following amounts to the Defendant’s wife’s account in the amounts and on the dates that follow:

a. $93,750 on January 21, 2020; and

b. $46,875 on May 26, 2020.

There was certainly enough in my post such that Scarsi didn’t have to infer that Stone’s two years of alleged invasion and fraud more closely mirror Hunter’s than he let on.

The comparison was never going to be the basis for dismissal. But because of the way Scarsi minimizes this, the comparison with another “American [who] earn[s] millions of dollars of income in a four-year period and [wrote] a memoir allegedly memorializing criminal activity” will be ripe for inclusion in any appeal, particularly if — as I expect — Hunter’s team demonstrates at trial how prosecutors have mistaken a memoir of addiction as an autobiography, one that hurts their tax case as much as it helps.

Scarsi accuses Lowell of post hoc argument

As noted above, when Scarsi loudly accused Abbe Lowell of presenting no evidence to support his selective and vindictive prosecution claim at his motions hearing, he was making a procedural comment about the way Lowell laid out evidence that pressure from Republicans and the IRS agents led Weiss to renege on a plea deal and file the 9-count indictment before Scarsi.

Scarsi has not rejected Lowell’s belated filing with such a declaration, which leaves me uncertain about whether those materials are now (and therefore were) formally before Scarsi before he ruled, even if only minutes before.

For both the IRS challenge and the general selective and vindictive claim, Scarsi ruled that Lowell had not reached the very high bar for such things. As I noted above, that is the easy decision, one that would almost always be upheld on appeal. These are not, on their face, controversial decisions at all.

Where those decisions become interesting, in my opinion — or could become interesting if they were included along with the inevitable appeal of the weird immunity decision — is in how he rejected those claims.

At the hearing, Judge Scarsi asked Abbe Lowell if he had any evidence of vindictive prosecution besides the timeline laid out in his filing, which relies on all those newspaper articles. Lowell conceded the timeline is all he had, but that “it’s a juicy timeline.” (Wise and Hines both wailed that the description of all this impugns them, an act that is getting quite tired but seemed to work like a charm for Scarsi.)

At the hearing, Lowell reportedly included several things in this discussion:

- The existence of an already agreed plea and diversion in June

- Congressman Jason Smith’s efforts to intervene in the plea hearing

- Leo Wise reneging at the plea hearing on earlier assurances there was no ongoing investigation into Hunter Biden, followed by Weiss’ immediate effort to strip all immunity from the diversion agreement

- The resuscitation of the Alexander Smirnov allegations

- A claim (that may reflect ignorance of some grand jury testimony) that, in the tax case, Weiss already had all the evidence in his possession that he had in June 2023 when he decided to pursue only misdemeanors

- The fact that, in the gun case, Weiss didn’t pursue basic investigative steps (like getting a gun crimes warrant for the laptop content or sending the gun pouch to the lab to be tested for residue) until after charging Hunter

- The subpoena to Weiss and his testimony just weeks before the tax indictment

In response to Lowell emphasizing these parts of the timeline — not a single one of which relies exclusively on news reports — the Judge who misused the phrase “beg the question” cited two Ninth Circuit precedents, neither of which Weiss relied on, to accuse Lowell of making a post hoc argument.

At best, Defendant draws inferences from the sequence of events memorialized in reporting, public statements, and congressional proceedings pertaining to him to support his claim that there is a reasonable likelihood he would not have been indicted but for hostility or punitive animus. As counsel put it at the hearing, “It’s a timeline, but it’s a juicy timeline.” But “[t]he timing of the indictment alone . . . is insufficient” to support a vindictiveness theory. Brown, 875 F.3d at 1240; see also United States v. Robison, 644 F.2d 1270, 1273 (9th Cir. 1981) (rejecting appearance-of-vindictiveness claim resting on “nothing more than the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy”). [links added]

Neither of these opinions are about timelines. Brown involves a case where someone already convicted of a federal weapons crime but awaiting trial in a state murder case escaped; after he made a declaration at his cellmate’s trial for escaping, he was charged himself for escaping. The Ninth Circuit ruled that was not vindictive because prosecutors got newly obtained evidence — his own declaration — with which to charge him for escaping.

Robison involves another case of newly discovered evidence. Several months after a state murder conviction was overturned and as he was appealing a charge for destroying a Federal building, he was charged with burning down a tavern. The court held a hearing (this was back in 1980, when such things were still done), and determined that the evidence implicating Robison in the tavern bombing post-dated his appeals.

Now, Weiss would argue (but curiously has always stopped well short of doing so) that he did get new evidence: He called a bunch of witnesses before a CA grand jury. Best as I can tell, the only thing Lowell has seen from that was testimony used in the warrant to search the laptop for gun crimes after the indictment. In neither LA nor in Delaware is Weiss arguing he got new information (while Weiss did serve a bunch of subpoenas for documents against Hunter, it’s not clear how many witness interviews were part of his apparently abandoned attempt to charge Hunter and his father with bribery). Unlike Jack Smith, Special Counsel Weiss appears not to be sharing all the grand jury testimony against Hunter.

But neither of these cases (as distinct from Bordenkircher and Goodwin) involve a prosecutor upping the ante on the same crimes as Weiss did. More importantly, they were offered to defeat Lowell’s claim of a timeline, a whole series of events. In response, Scarsi offers up cases that involve two (arguably, three with Robison) events.

Lowell’s timeline focuses closely on June and July, not December, and yet Scarsi adopts precedents that focus on the timing of an indictment, not a reneged plea.

I’m interested not so much that these citations are inapt (but they are). It’s what Scarsi does to dismantle Lowell’s timeline.

Scarsi corrects, and then fiddles with, and in two places, ignores the timeline

Scarsi is absolutely right that Hunter’s initial motion is a mess (remember that Lowell had asked for an extension in part because the lawyer responsible for these filings had a death in the family; I suspect that Scarsi had his opinion on this motion written before the hearing and possibly even before the reply). Scarsi makes much, correctly, of several details Lowell erroneously suggests immediately preceded the December tax indictment.

Moreover, Defendant appears to suggest that, after the deal in Delaware fell apart but before the filing of the indictment in this case, Mr. Trump “joined the fray, vowing that if DOJ does not prosecute Mr. Biden for more, he will ‘appoint a real special prosecutor to go after’ the ‘Biden crime family,’ ‘defund DOJ,’ and revive an executive order allowing him to fire Executive Branch employees at will.” (Id. at 7.) The comments he cites all predate the unraveling of the Delaware plea—if not even earlier, before the announcement of a plea.

But in correcting that error, Scarsi has noted (what the Delaware motion does note) that Trump’s attacks on Weiss were an immediate response to the publication of the plea agreement.

And that’s interesting, because Scarsi repeatedly fiddles with the timeline on his own accord.

For example, he starts the entire opinion by laying out what he claims is “a brief background of undisputed events leading up to the Indictment.” In it, he astonishingly declines to date the plea agreement — which was publicly docketed on June 20 — anytime before late July 2023.

By late July 2023, Defendant and the Government reached agreement on a resolution of the tax charges and the firearm charges memorialized in two separate agreements: a memorandum of plea agreement resolving the tax offenses, (Machala Decl. Ex. 3 (“Plea Agreement”), ECF No. 25-4), and a deferred prosecution agreement, or diversion agreement, addressing the firearm offenses, (Machala Decl. Ex. 2 (“Diversion Agreement”), ECF No. 25-3).

So for the opinion as a whole, Scarsi has simply post-dated events that unquestionably happened a month earlier. Much later in the opinion, however, Scarsi cites the evidence (accompanied by a declaration) that that decision happened in June.

On May 15, 2023, prosecutors proposed “a non-charge disposition to resolve any and all investigations by the DOJ of Mr. Biden.” (Clark Decl. ¶ 6.)26 After further discussions over the following month, Defendant and the Government coalesced around a deal involving a deferred prosecution agreement and a plea to misdemeanor tax charges. (See generally id. ¶¶ 7–39.)

Having post-dated the actual prosecutorial decision filed to docket in June, Scarsi repeatedly says that Hunter doesn’t have any way of knowing when any prosecutorial decisions happened. In one place, he makes the fair assertion that Hunter hasn’t substantiated when particular decisions were made.

Defendant asserts that a presumption of vindictiveness arises because the Government repeatedly “upp[ed] the ante right after being pressured to do so or Mr. Biden trying to enforce his rights.” (Selective Prosecution Mot. 16.) Defendant alleges a series of charging decisions by the prosecution, (id. at 4–7), but the record does not support an inference that the prosecutors made them when Defendant says they did.

[snip]

But the fact of the matter is that the Delaware federal court did not accept the plea, the parties discussed amendments to the deal they struck toward satisfying the court’s concerns, and the deal subsequently fell through.

In another, he makes the ridiculous assertion that Hunter has not substantiated when any prosecutorial decisions were made.

Defendant asserts that the Government made numerous prosecuting decisions between 2019 and 2023 without offering any substantiating proffer that such decisions were made before the Special Counsel decided to present the charges to the grand jury, let alone any proffer that anyone outside the Department of Justice affected those decisions, let alone any proffer that any of those decisions were made based on unjustifiable standards.

Hunter presented authenticated, undisputed proof regarding when one prosecutorial decision was made, and it was made in June, not July, where (in one place) Scarsi misplaces it.

Similarly, Scarsi distorts the timeline when Leo Wise reneged on the assurances that there was no further investigation. He admits that prosecutors withdrew all immunity offer in August, but dates it to after the plea hearing, not before (as represented by Wise’s comment about an ongoing investigation).

On July 26, 2023, the district judge in Delaware deferred accepting Defendant’s plea so the parties could resolve concerns raised at the plea hearing. (See generally Del. Hr’g Tr. 108–09.) That afternoon, Defendant’s counsel presented Government counsel a menu of options to address the concerns. (Def.’s Suppl. Ex. C, ECF No. 58-1.)31 On July 31, Defendant’s counsel and members of the prosecution team held a telephone conference in which they discussed revising the Diversion Agreement and Plea Agreement. The Government proposed amendments and deletions. (See Lowell Decl. Ex. B, ECF No. 48-3.) On August 7, counsel for Defendant responded in writing to these proposals, signaling agreement to certain modifications but resisting the Government’s proposal to modify the provision of the Diversion Agreement contemplating court adjudication of any alleged breaches and to delete the provision conferring immunity to Defendant. Defense counsel took the position that the parties were bound to the Diversion Agreement. (Id.) On August 9, the Government responded in writing, taking the position that the Diversion Agreement was not in effect, withdrawing its proposed modifications offered on July 31 in addition to the versions of the agreements at play on July 26, and signaling that it would pursue charges. (Def.’s Suppl. Ex. C.)

In the section of his opinion discussion selective prosecution, he accepts that the IRS agents first started leaking in May 2023, but finds — having heard Leo Wise’s misleading claim that he knew of no effect the disgruntled IRS agents had and having also acknowledged that Weiss himself testified that he was afraid for his family’s safety (but leaving it out of all his timeline discussions) — that Lowell presented no evidence that Shapley and Ziegler affected Weiss’ decision-making.

Meanwhile, in late May, Internal Revenue Service agents spoke to news media and testified before the Ways and Means Committee of the United States House of Representatives about their involvement in the tax investigation of Defendant. E.g., Jim Axelrod et al., IRS whistleblower speaks: DOJ “slow walked” tax probe said to involve Hunter Biden, CBS News (May 24, 2023, 8:31 p.m.), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/irs-whistleblower-tax-probe-hunter-biden/ [https://perma.cc/7GQF-2HJA]; Michael S. Schmidt et al., Inside the Collapse of Hunter Biden’s Plea Deal, N.Y. Times (Aug. 19, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/19/us/politics/inside-hunter-biden-pleadeal.html [https://perma.cc/6CVJ-KYDK].27

27 Defendant asserts that the IRS agents’ actions prompted then-United States Attorney David Weiss to change his position away from a non-charge disposition to the plea the parties ultimately contemplated, (Selective Prosecution Mot. 5 & nn.11–12), but the support for this assertion apparently is his own attorneys’ and the IRS agents’ speculation as reported by the New York Times, see Schmidt et al., supra (“Mr. Biden’s legal team agrees that the I.R.S. agents affected the deal . . . .”). For the same story, Mr. Weiss declined to comment, and an unnamed law enforcement official disputed the assertion. Id.

Later in that section, having made his big show of rejecting Weiss’ bid to limit the consideration of IRS influence just to grand jury decisions but then flip-flopped, Scarsi decides that he’s not going to look too closely at this timing (for the egregious violation motion).

43 The particulars of when and how Defendant asserts Shapley and Ziegler made these disclosures, and what their contents were, are immaterial to this Order. The Court declines to make any affirmative findings that Shapley and Ziegler violated these rules given the pending civil case Defendant brought against the IRS related to the alleged disclosures, see generally Complaint, Biden v. U.S. IRS, No. 1:23-cv-02711-TJK (D.D.C. Sept. 18, 2023), ECF No. 1, and the potential for criminal prosecution of such violations. But the Court need not resolve whether their public statements ran afoul of these nondisclosure rules to decide the motion.

That — plus Wise’s misleading comment — is how Scarsi dismisses Lowell’s claim that the IRS agents had a role in killing the plea deal.

(“There is no doubt that the agents’ actions in spring and summer 2023 substantially influenced then-U.S. Attorney Weiss’s decision to renege on the plea deal last summer, and resulted in the now-Special Counsel’s decision to indict Biden in this District.”).) His theory rests on a speculative inference of causation supported only by the sequence of events.

Meanwhile, his efforts to dismiss the import of Congress’ and Trump’s earlier intervention is uneven. Scarsi’s treatment of this passage from Hunter’s motion deserves closer consideration:

Mr. Biden agreed to plead guilty to the tax misdemeanors, but when the plea deal was made public, the political backlash was forceful and immediate. Even before the Delaware court considered the plea deal on July 26, 2023, extremist Republicans were denouncing it as a “sweetheart deal,” accusing DOJ of misconduct, and using the excuse to interfere with the investigation.13 [2] Leaders of the House Judiciary, Oversight and Accountability, and Ways and Means Committees (“HJC,” “HOAC,” and “HWMC,” respectively) opened a joint investigation, and on June 23, HWMC Republicans publicly released closed-door testimony from the whistleblowers, who, in the words of Chairman Smith, “describe how the Biden Justice Department intervened and overstepped in a campaign to protect the son of Joe Biden by delaying, divulging and denying an ongoing investigation into Hunter Biden’s alleged tax crimes.”14 Then, one day before Mr. Biden’s plea hearing, Mr. Smith tried to intervene [4] to file an amicus brief “in Aid of Plea Hearing,” in which he asked the court to “consider” the whistleblower testimony.15

13 Phillip Bailey, ‘Slap On The Wrist’: Donald Trump, Congressional Republicans Call Out Hunter Biden Plea Deal, USA Today (June 20, 2023), https://www.usatoday.com/.

14 Farnoush Amiri, GOP Releases Testimony Alleging DOJ Interference In Hunter Biden Tax Case, PBS (June 23, 2023), https://www.pbs.org/.

15 United States v. Biden, No. 23-mj-00274-MN (D. Del. 2023), DE 7. [brackets mine]

Here’s how Scarsi treats this passage laying out what happened between the publication of the plea and the failed plea hearing:

The putative [sic] plea deal became public in June 2023. Several members of the United States Congress publicly expressed their disapproval on social media. The Republican National Committee stated, “It is clear that Joe Biden’s Department of Justice is offering Hunter Biden a sweetheart deal.” Mr. Trump wrote on his social media platform, “The corrupt Biden DOJ just cleared up hundreds of years of criminal liability by giving Hunter Biden a mere ‘traffic ticket.’” Phillip M. Bailey, ‘Slap on the wrist’: Donald Trump, congressional Republicans call out Hunter Biden plea deal, USA Today (June 20, 2023, 11:17 a.m.), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2023/06/20/donald-trump-republicans-react-hunter-biden-plea-deal/ 70337635007/ [https://perma.cc/TSN9-UHLH]. 28 On June 23, 2023, the Ways and Means Committee of the United States House of Representatives voted to publicly disclose congressional testimony from the IRS agents who worked on the tax investigation. Jason Smith, chair of the Ways and Means Committee, told reporters that the agents were “[w]histleblowers [who] describe how the Biden Justice Department intervened and overstepped in a campaign to protect the son of Joe Biden by delaying, divulging and denying an ongoing investigation into Hunter Biden’s alleged tax crimes.” Farnoush Amiri, GOP releases testimony alleging DOJ interference in Hunter Biden tax case, PBS NewsHour (June 23, 2023, 3:58 p.m.), https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/gop-releases-testimony-alleging-dojinterference-in-hunter-biden-tax-case.29 One day before the plea hearing in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware, Mr. Smith moved to file an amicus curiae brief imploring the court to consider the IRS agents’ testimony and related materials in accepting or rejecting the plea agreement. Mem. of Law in Support of Mot. for Leave to File Amicus Curiae Br., United States v. Biden, No. 1:23-mj-00274-MN (D. Del. July 25, 2023), ECF No. 7-2; Amicus Curiae Br., United States v. Biden, No. 1:23-mj-00274-MN (D. Del. July 25, 2023), ECF No. 7-3.30

28 This source does not stand for the proposition that “extremist Republicans were [1] . . . using the excuse to interfere with the investigation.” (Selective Prosecution Mot. 5–6.) Of Mr. Weiss, Mr. Trump also wrote: “He gave out a traffic ticket instead of a death sentence. . . . Maybe the judge presiding will have the courage and intellect to break up this cesspool of crime. The collusion and corruption is beyond description. TWO TIERS OF JUSTICE!” Ryan Bort, Trump Blasts Prosecutor He Appointed for Not Giving Hunter Biden ‘Death Sentence,’ Rolling Stone (July 11, 2023), https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/trump-suggests-hunter-bidendeath penalty-1234786435/ [https://perma.cc/UH6N-838R].

29 This source does not stand for the proposition that several leaders of house committees “opened a joint investigation.” (Selective Prosecution Mot. 6.) [3]

30 The docket does not show that the Delaware district court resolved the motion, and the Court is uncertain whether the court considered Mr. Smith’s brief. [brackets mine]

First, Scarsi uses an ellipsis, marked at [1], to suggest the only reason Lowell cited the USA Today story was to support the claim that Republicans moved to intervene in the investigation, when the sentence in question includes three clauses, two of which the story does support. The sentence immediately following that three-clause sentence [2] makes a claim — OGR, HWAM, and HJC forming a joint committee, that substantiates that claim. Scarsi’s complaint at [3] is not that the cited article does not include Jason Smith’s quotation; rather, it’s that Lowell has not pointed to a source for the formation of a joint investigation (a later-cited source that Scarsi never mentions does include it). Meanwhile, Scarsi applies a measure — whether Judge Noreika considered Smith’s amicus, not whether he tried to file it — that Lowell doesn’t make (and which is irrelevant to a vindictive prosecution motion, because Noreika is not the prosecutor); Smith did succeed in getting the amicus unsealed, including the exhibits that Hunter claimed include grand jury materials. Whether or not Judge Noreika considered the content of the amicus, that Smith filed it is undeniable proof that Smith tried to intervene, which is all Hunter alleged he did.

Meanwhile, Scarsi relegates Trump’s Social Media threats — which Scarsi later corrects Lowell by noting that they came during precisely this period — to a footnote.

Here’s one thing I find most interesting. Scarsi’s two most valid complaints about Lowell’s filing are that, in one part of his timeline but not another, he misrepresented Trump’s pressure as happening after the plea failed, and that Lowell claimed that Weiss testified he had gotten death threats when instead the cited source (and the Weiss transcript I assume Lowell does not have) instead say that Weiss feared for his family. He acknowledges both those things: Trump attacked Weiss, and Weiss got threats that led him to worry for the safety of his family.

But he never considers Weiss’ fear for his family’s safety in his consideration of what happened between June and July. He never considers whether those threats had a prejudicial affect on Hunter Biden.

And aside from that correction regarding the safety comment, nor does Scarsi consider the most direct aspect of Congress’ intervention in the case — that Congress demanded Weiss testify, and he did so just weeks before he filed the charges actually before Scarsi.

In other words, Scarsi accuses Lowell of making a post hoc argument, claiming that he is simply pointing to prior events to explain Weiss’ subsequent actions. Except he ignores the impact of the two most direct allegations of influence.

Lowell did neglect to notice one important detail

There is one detail that Scarsi entirely ignores — but it’s one area where Lowell’s failures to provide evidence may be the most problematic.

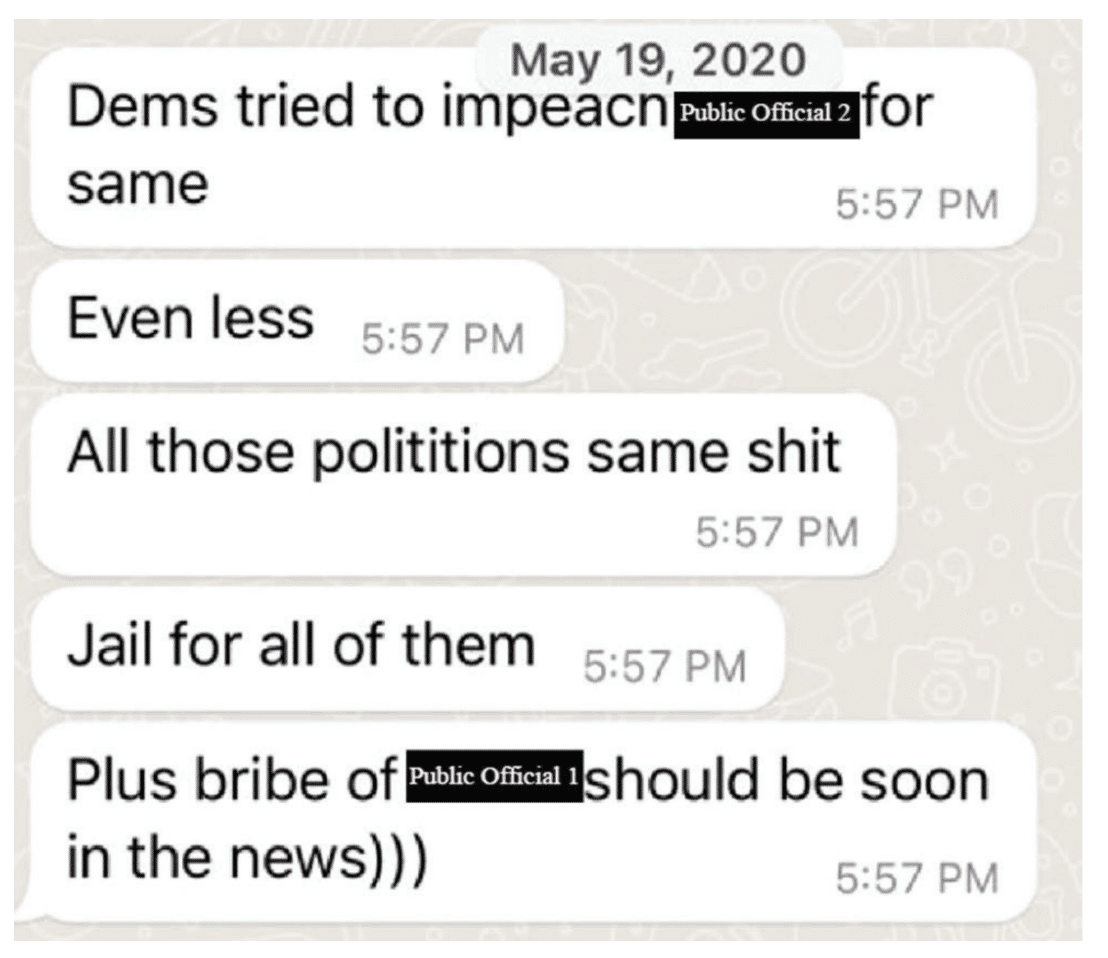

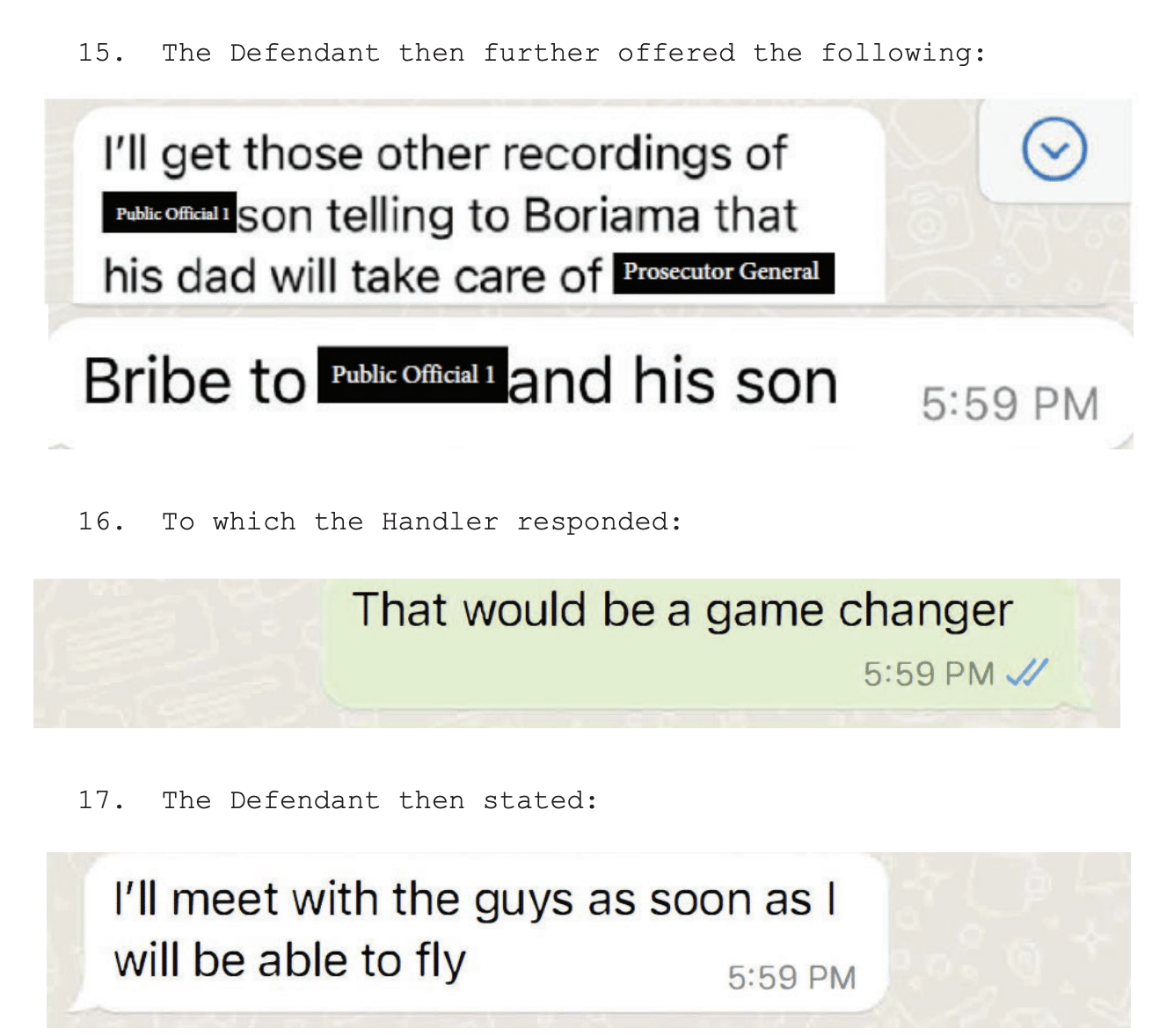

Scarsi doesn’t mention Alexander Smirnov.

But it’s not clear the Smirnov case is properly before Scarsi.

He was definitely mentioned. Weiss first raised Smirnov, though without providing docket information, and Lowell responded.

But as I laid out here, while both discovery requests pertaining to the Brady side channel as well as a notice of the Smirnov indictment are before Judge Noreika, neither filing was repeated before Scarsi. There are allusions to it — such as Jerry Nadler’s efforts to chase down the Brady side channel, but not formal notification in court filings of the FD-1023 or Smirnov’s arrest.

In his introduction to the selective prosecution section, Scarsi noted that there was more in the docket in Delaware, stuff he was not going to consider (which leads me to believe he’s got something specific in mind that he is excluding).

20 The parties freely refer to briefs they filed in connection with a motion to dismiss filed in the criminal case against Defendant pending in Delaware, in which the parties advanced similar arguments, but more voluminously. Although the Court has read the Delaware briefing, (see Tr. 13, ECF No. 18), its resolution of the motion rests only on the arguments and evidence presented in the filings in this case. See United States v. Sineneng-Smith, 140 S. Ct. 1575, 1579 (2020). [link added]

Scarsi’s citation seems to suggest that arguments not made before him by Lowell would be improper to consider. But at least with respect to Lowell’s request for the materials on the side channel, it has never been clear whether Lowell was supposed to repeat discovery requests before Scarsi he already made in Delaware.

One way or another, though, Scarsi has not formally considered the abundant evidence that the reason Leo Wise reneged on past assurances that there was no ongoing investigation was so he could chase Smirnov’s false claims of bribery. There are ways that Lowell could present that as new news, but it seems that Scarsi maintains that he has not yet done so, not even when prosecutors were the first to raise it.

As I keep saying, Scarsi’s decision on the selective prosecution and the egregious misconduct are not wrong. But the way in which he rejected them provide reason for complaint.

Lowell has strongly suggested that he will appeal this decision (but he likely cannot do so unless Hunter is found guilty). If that happens, it’s likely these weaknesses in Scarsi’s opinion — his failure to adhere to his own admirably rigorous standards — may make the opinion more vulnerable to appeal.

Update: Note I’ve updated my Hunter Biden page and also added Alexander Smirnov to my nifty Howard Johnson graphic.