Ladar Levison’s interview with Amy Goodman yesterday was his most extensive statement about the demand he got that led him to shut down his company. I want to pull the important tidbits from that interview and this one, with Forbes’ Kashmir Hill, to collect what we know about the demand so far.

Levison told DN the entire service was insecure:

I felt that in the end I had to pick between the lesser of two evils and that shutting down the service, if it was no longer secure, was the better option. It was, in effect, the lesser of the two evils.

He told Hill that he shut down to protect all his users.

“This is about protecting all of our users, not just one in particular. It’s not my place to decide whether an investigation is just, but the government has the legal authority to force you to do things you’re uncomfortable with,” said Levison in a phone call on Friday.

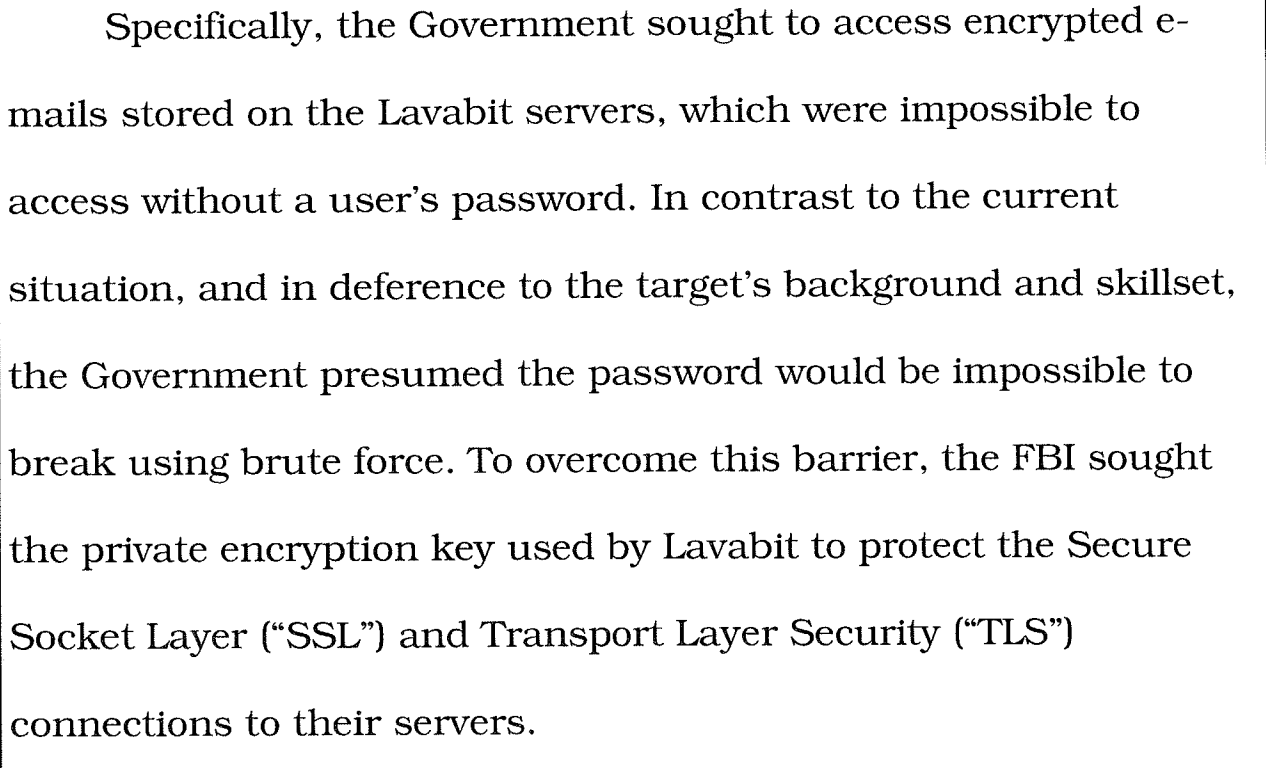

The demand affected his paid users and involved him being forced to have access to the private information the system was designed to ensure he didn’t have.

And at least for our paid users, not for our free accounts—I think that’s an important distinction—we offered secure storage, where incoming emails were stored in such a way that they could only be accessed with the user’s password, so that, you know, even myself couldn’t retrieve those emails.

[snip]

in our case it was encrypted in secure storage, because, as a third party, you know, I didn’t want to be put in a situation where I had to turn over private information. I just didn’t have it. I didn’t have access to it. And that was sort of—may have been the situation that I was facing.

Levison told Hill he has complied with legal requests where the requested information was not encrypted (suggesting it involved his free users).

“I’m not trying to protect people from law enforcement,” he said. “If information is unencrypted and law enforcement has a court order, I hand it over.”

Snowden was a registered user of Lavabit, apparently under his own name.

Ladar, you were the service provider for Edward Snowden?

LADAR LEVISON: I believe that’s correct. Obviously, I didn’t know him personally, but it’s been widely reported, and there was an email account bearing his name on my system, as I’ve been made well aware of recently.

The government has prevented Levison from sharing some of the demand with his lawyer. And Levison thinks that’s because the government would be ashamed of the nature of the demand.

I mean, there’s information that I can’t even share with my lawyer, let alone with the American public. So if we’re talking about secrecy, you know, it’s really been taken to the extreme. And I think it’s really being used by the current administration to cover up tactics that they may be ashamed of.

He told Hill, too, the method they were demanding is what bothered him.

In this case, it is the government’s method that bothers him. “The methods being used to conduct those investigations should not be secret,” he said.

Update: In an interview w/MoJo, he suggests the demand pertains to bulk collection on an entire user base of people.

While Levison of Lavabit could not discuss the specifics of his case, he suggested that the government was trying to compel him to give access to vast quantities of user data. He explained that he was not opposed to fulfilling law enforcement requests that were “specific in nature” and “approved by a judge after showing probable cause,” and noted that he had responded to some two dozen subpoenas during his decade in business. “What I’m against, at least on a philosophical level,” he added, “is the bulk collection of information, or the violation of the privacy of an entire user base just to conduct the investigation into a handful of individuals.”

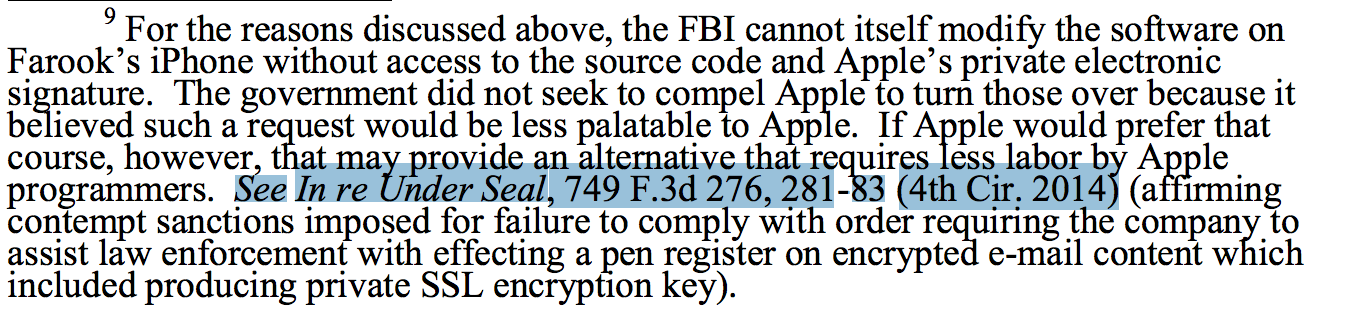

And suggested if they could intercept communications between the servers and the user, they could decrypt the communications.

if someone could intercept the communication between the Lavabit’s Dallas-based servers and a user, they could get the user’s password and then use that to decrypt their data.

What distinguishes this from previous subpoenas is what is so secret.

AARON MATÉ: And, Ladar, during this time, you’ve complied with other government subpoenas. Is that correct?

LADAR LEVISON: Yeah, we’ve probably had at least two dozen subpoenas over the last 10 years, from local sheriffs’ offices all the way up to federal courts. And obviously I can’t speak to any particular one, but we’ve always complied with them. I think it’s important to note that, you know, I’ve always complied with the law. It’s just in this particular case I felt that complying with the law—

JESSE BINNALL: And we do have to be careful at this point.

LADAR LEVISON: Yeah, I—

Levison questions whether it is possible to run cloud service in this country without being forced to spy on your customers.

I still hope that it’s possible to run a private service, private cloud data service, here in the United States without necessarily being forced to conduct surveillance on your users by the American government.

Levison suggests both his and Silent Circle’s unannounced shut-down served to avoid government efforts to capture data beforehand.

Mike Janke, Silent Circle’s CEO and co-founder, said, quote, “There was no 12-hour heads up. If we announced it, it would have given authorities time to file a national security letter. We decided to destroy it before we were asked to turn (information) over. We had to do scorched earth.” Ladar, your response?

LADAR LEVISON: I can certainly understand his position. If the government had learned that I was shutting my service down—can I say that?

JESSE BINNALL: Well, I think it’s best to kind of avoid that topic, unfortunately. But I think it is fair to say that Silent Circle was probably in a very different situation than Lavabit was, and which is probably why they took the steps that they did, which I think were admirable.

LADAR LEVISON: Yeah. But I will say that I don’t think I had a choice but to shut it down without notice. I felt that was my only option. And I’ll have to leave it to your listeners to understand why.

Everything is being monitored.

LADAR LEVISON: I think you should assume any communication that is electronic is being monitored.

This echoes something Levison told Forbes’ Kashmir Hill:

“I’m taking a break from email,” said Levison. “If you knew what I know about email, you might not use it either.”

Levison also told Hill his location in Texas made it harder to respond to a demand in VA.

“As a Dallas company, we weren’t really equipped to respond to this inquiry. The government knew that,” said Levison, who drew parallels with the prosecutorial bullying of Aaron Swartz. “The same kinds of things have happened to me. The government tried to bully me, and [my lawyer] has been instrumental in protecting me, but it’s amazing the lengths they’ve gone to to accomplish their goals.”

His statement shuttering the company mentioned an appeal to the Fourth Circuit, which includes VA, and the complaint against Edward Snowden was issued in EDVA.

Update: I hadn’t watched the continuation of the DN interview, where Nicholas Merrill, who challenged a National Security Letter back in 2004, came on. But as CDT’s Joseph Lorenzo Hall notes on Twitter, Levison strongly suggests his order came from the FISA Court.

LADAR LEVISON: I think it’s important to note that, you know, it’s possible to receive one of these orders and have it signed off on by a court. You know, we have the FISA court, which is effectively a secret court, sometimes called a kangaroo court because there’s no opposition, and they can effectively issue what we used to consider to be an NSL. And it has the same restrictions that your last speaker, your last guest, just talked about.

Hall also has an interesting piece on Lavabit and CALEA II that addresses issues I’ve been thinking about, in which he includes this discussion.

What did the government demand and under what authority prompted Lavabit’s shutdown? We don’t know, and that’s part of the problem. The Wiretap Act, which authorizes the government to intercept communications content prospectively in criminal investigations, indicates that a provider of wire or electronic communication service (such as Lavabit) can be compelled to furnish law enforcement with “all information, facilities and technical assistance necessary to accomplish the interception unobtrusively… .” 18 USC 2518(4). The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), which regulates surveillance in intelligence investigations, likewise requires any person specified in a surveillance order to provide the same assistance (50 USC 1805(2)(B)) and so does the FISA Amendments Act with respect to directives for surveillance targeting people and entities reasonably believed to be abroad (50 USC 1881a(h)(1)). The “assistance” the government demands may include the disclosure of the password information necessary to decrypt the communications it seeks, if the service provider has that information, but modern encryption services can be designed so that the service provider does not hold the keys or passwords. Was the “assistance” that the government demanded of Lavabit a change in the very architecture of its secure email service? Was the “assistance” the installation of the government’s own malware to accomplish the same thing? Lavabit has not answered these questions outright, but it did make it clear that its concern extended to the privacy of the communications of all of its users, not just those of one user under one court order.