During the July 1 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on back doors, Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates claimed that the government doesn’t want the government to have back doors into encrypted communications. Rather, they wanted corporations to retain the back doors to be able to access communications if the government had legal process to do so. (After 1:43.)

We’re not going to ask the companies for any keys to the data. Instead, what we’re going to ask is that the companies have an ability to access it and then with lawful process we be able to get the information. That’s very different from what some other countries — other repressive regimes — from the way that they’re trying to get access to the information.

The claim was bizarre enough, especially as she went on to talk about other countries not having the same lawful process we have (as if that makes a difference to software code).

More importantly, that’s not true.

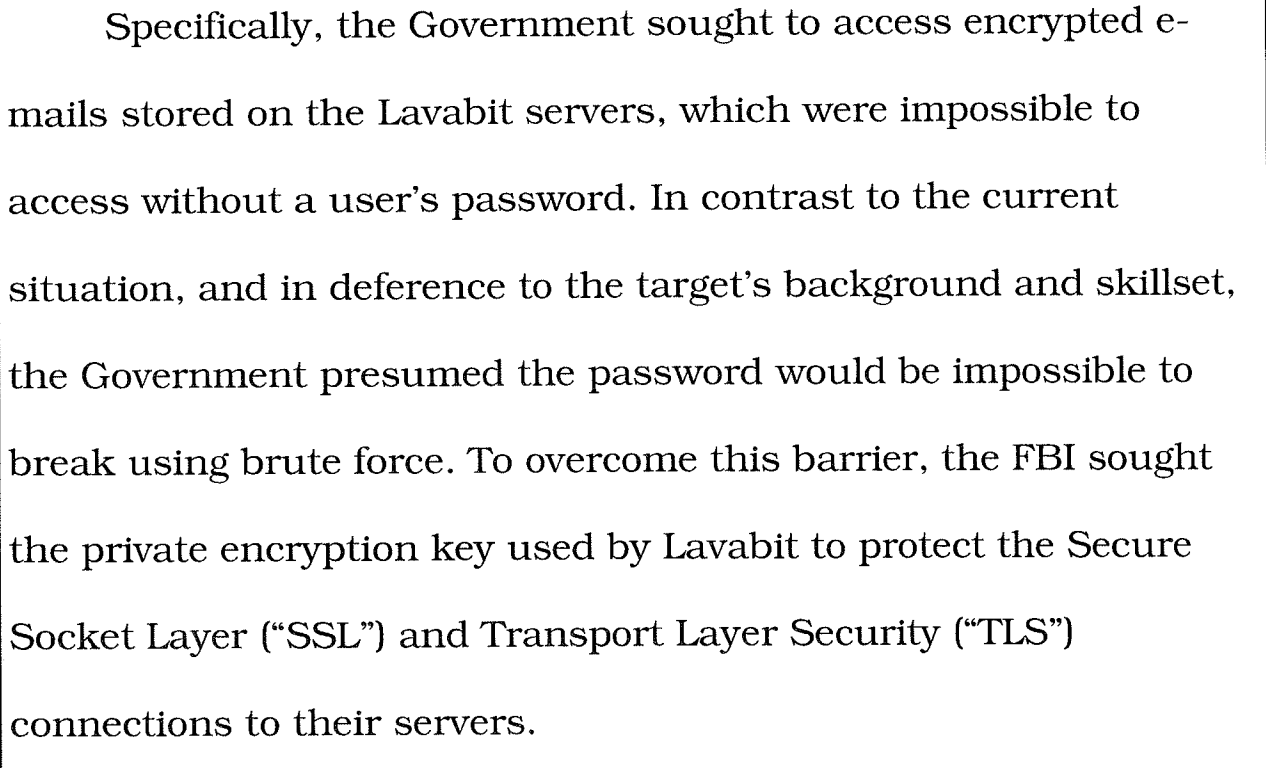

Remember what happened with Lavabit, when the FBI was in search of what is presumed to be Edward Snowden’s email. Lavabit owner Ladar Levison had a discussion with FBI about whether it was technically feasible to put a pen register on the targeted account. After which the FBI got a court order to do it. Levison tried to get the government to let him write a script that would provide them access to just the targeted account or, barring that, provide for some kind of audit to ensure the government wasn’t obtaining other customer data.

The unsealed documents describe a meeting on June 28th between the F.B.I. and Levison at Levison’s home in Dallas. There, according to the documents, Levison told the F.B.I. that he would not comply with the pen-register order and wanted to speak to an attorney. As the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, Neil MacBride, described it, “It was unclear whether Mr. Levison would not comply with the order because it was technically not feasible or difficult, or because it was not consistent with his business practice in providing secure, encrypted e-mail service for his customers.” The meeting must have gone poorly for the F.B.I. because McBride filed a motion to compel Lavabit to comply with the pen-register and trap-and-trace order that very same day.

Magistrate Judge Theresa Carroll Buchanan granted the motion, inserting in her own handwriting that Lavabit was subject to “the possibility of criminal contempt of Court” if it failed to comply. When Levison didn’t comply, the government issued a summons, “United States of America v. Ladar Levison,” ordering him to explain himself on July 16th. The newly unsealed documents reveal tense talks between Levison and the F.B.I. in July. Levison wanted additional assurances that any device installed in the Lavabit system would capture only narrowly targeted data, and no more. He refused to provide real-time access to Lavabit data; he refused to go to court unless the government paid for his travel; and he refused to work with the F.B.I.’s technology unless the government paid him for “developmental time and equipment.” He instead offered to write an intercept code for the account’s metadata—for thirty-five hundred dollars. He asked Judge Hilton whether there could be “some sort of external audit” to make sure that the government did not take additional data. (The government plan did not include any oversight to which Levison would have access, he said.)

Most important, he refused to turn over the S.S.L. encryption keys that scrambled the messages of Lavabit’s customers, and which prevent third parties from reading them even if they obtain the messages.

The discussions disintegrated because the FBI refused to let Levison do what Yates now says they want to do: ensure that providers can hand over the data tailored to meet a specific request. That’s when Levison tried to give FBI his key in what it claimed (even though it has done the same for FOIAs and/or criminal discovery) was in a type too small to read.

On August 1st, Lavabit’s counsel, Jesse Binnall, reiterated Levison’s proposal that the government engage Levison to extract the information from the account himself rather than force him to turn over the S.S.L. keys.

THE COURT: You want to do it in a way that the government has to trust you—

BINNALL: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: —to come up with the right data.

BINNALL: That’s correct, Your Honor.

THE COURT: And you won’t trust the government. So why would the government trust you?

Ultimately, the court ordered Levison to turn over the encryption key within twenty-four hours. Had the government taken Levison up on his offer, he may have provided it with Snowden’s data. Instead, by demanding the keys that unlocked all of Lavabit, the government provoked Levison to make a last stand. According to the U.S. Attorney MacBride’s motion for sanctions,

At approximately 1:30 p.m. CDT on August 2, 2013, Mr. Levison gave the F.B.I. a printout of what he represented to be the encryption keys needed to operate the pen register. This printout, in what appears to be four-point type, consists of eleven pages of largely illegible characters. To make use of these keys, the F.B.I. would have to manually input all two thousand five hundred and sixty characters, and one incorrect keystroke in this laborious process would render the F.B.I. collection system incapable of collecting decrypted data.

The U.S. Attorneys’ office called Lavabit’s lawyer, who responded that Levison “thinks” he could have an electronic version of the keys produced by August 5th.

Levison came away from the debacle believing that the FBI didn’t understand what it was asking for when they asked for his keys.

One result of this newfound expertise, however, is that Levison believes there is a knowledge gap between the Department of Justice and law-enforcement agencies; the former did not grasp the implications of what the F.B.I. was asking for when it demanded his S.S.L. keys.

I raise all this because of the rumor — which Bruce Schneier inserted into his excerpt of this Nicholas Weaver post — that FBI is already fighting before FISC with Apple for a back door.

There’s a persistent rumor going around that Apple is in the secret FISA Court, fighting a government order to make its platform more surveillance-friendly — and they’re losing. This might explain Apple CEO Tim Cook’s somewhat sudden vehemence about privacy. I have not found any confirmation of the rumor.

Weaver’s post describes how, because of the need to allow users to access their iMessage account from multiple devices (think desktop, laptop, iPad, and phone), Apple technically could give FBI a key.

In iMessage, each device has its own key, but its important that the sent messages also show up on all of Alice’s devices. The process of Alice requesting her own keys also acts as a way for Alice’s phone to discover that there are new devices associated with Alice, effectively enabling Alice to check that her keys are correct and nobody has compromised her iCloud account to surreptitiously add another device.

But there remains a critical flaw: there is no user interface for Alice to discover (and therefore independently confirm) Bob’s keys. Without this feature, there is no way for Alice to detect that an Apple keyserver gave her a different set of keys for Bob. Without such an interface, iMessage is “backdoor enabled” by design: the keyserver itself provides the backdoor.

So to tap Alice, it is straightforward to modify the keyserver to present an additional FBI key for Alice to everyone but Alice. Now the FBI (but not Apple) can decrypt all iMessages sent to Alice in the future.

Admittedly, as heroic as Levison’s decision to shut down Lavabit rather than renege on a promise he made to his customers, Apple has a lot more to lose here strictly because of the scale involved. And in spite of the heated rhetoric, FBI likely still trusts Apple more than they trusted Levison.

Still, it’s worth noting that Yates’ claim that FBI doesn’t want keys to communications isn’t true — or at least wasn’t before her tenure at DAG. Because a provider, Levison, insisted on providing his customers what he had promised, the FBI grew so distrustful of him they did demand a key.