Stephen Miller’s Snowballing Deportation Deceptions

I want to tell the story that NYT reports about Trump’s deal with Nayib Bukele to send people the Administration claims to be members of Tren de Aragua (TdA) to his concentration camp, including the critical details they left out. The entire deportation regime associated with TdA is built on a series of Stephen Miller lies, and as courts move towards discovery with the goal of holding those responsible in contempt, the stakes of Miller’s lies are going up.

- El Salvador Is Said to Have Spurned U.S. Request for Return of Deported Migrant (By Michael S. Schmidt, Alan Feuer, Zolan Kanno-Youngs, Maggie Haberman, and Maria Abi-Habib)

- Behind Trump’s Deal to Deport Venezuelans to El Salvador’s Most Feared Prison (By Zolan Kanno-Youngs, Hamed Aleaziz, Alan Feuer, Devlin Barrett, Julie Turkewitz, Jonathan Swan, Maggie Haberman, and Annie Correal)

- Five takeaways (By Zolan Kanno-Youngs, Hamed Aleaziz, Devlin Barrett, Jonathan Swan, Maggie Haberman, and Annie Correal)

As NYT’s stories lay out, starting at least as early as 2023, Stephen Miller viewed the Alien Enemies Act as a way to deport people with no due process.

Mr. Miller had long been interested in the Alien Enemies Act, a law passed in 1798 that allows the U.S. government to swiftly deport citizens of an invading nation. The authority has been invoked just three times in the past, all during times of war. He saw it as a powerful weapon to apply to immigration enforcement.

The law “allows you to instantaneously remove any noncitizen foreigner from an invading country, aged 14 or older,” Mr. Miller told the right-wing podcaster Charlie Kirk in a September 2023 interview, adding: “That allows you to suspend the due process that normally applies to a removal proceeding.”

During the campaign, Trump made overblown claims about TdA and Aurora, CO central to his campaign, and in real time associated those false claims with the AEA.

Though not mentioned in NYT’s opus, NYT’s Jonathan Weisman described the source of the false claims in September 2024. The claims about Aurora had been pitched by a slum landlord from NY — a man after Trump’s own heart — trying to project blame for his own neglect in caring for his properties, which quickly turned into a propaganda spiel on Murdoch outlets.

As far back as May 2023, Aurora officials had been trying to force an out-of-state landlord to fix up three blighted apartment complexes in the downtrodden East Colfax Corridor, which connects the cities of Denver and Aurora.

In July 2024, the landlord, CBZ Management, which says it is based in Colorado and Brooklyn, offered a new argument for why it couldn’t repair the buildings: Venezuelan gangs had taken over, and the property managers had been forced to flee.

Mr. Coffman and a Republican City Council member, Danielle Jurinsky, quickly repeated CBZ’s unverified claim in interviews.

“We have areas in our city, unfortunately, that have been taken, and we have to take back,” Mr. Coffman told a local talk radio host on July 31.

On Aug, 5, a public relations agent, Sara Lattman, hired by CBZ, pitched a “tip” to the local Fox television network affiliate in Denver.

“An apartment building and its owners in Aurora, Colorado have become the most recent victims of the Venezuelan Gang Tren de Aragua’s violence, which has taken over several communities in the Denver area,” she wrote on Fox 31’s tip line, according to an email obtained by The Times. “The residents and building owners of these properties have been left in a state of fear and chaos.”

But it was a viral video that began circulating in late August that shows armed men in the hallway of one of the complexes that ultimately caught Mr. Trump’s attention. The incident was reported as a connection to gang violence, particularly the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, though documentation was scarce.

On Tuesday, the Aurora Police Department announced it had arrested 10 members of Tren de Aragua on charges of ”felony menacing,” attempted first-degree murder, assault, child abuse, domestic abuse and others. But Todd Chamberlain, Aurora’s new police chief, could not say whether any of those men were among those seen in the video, or whether any in the video had actually done anything criminal.

Still, the clip, taken by a resident and played on endless loops on Fox News Channel and the website of The New York Post, metastasized into grandiose stories of whole buildings, whole sections of town and, in Mr. Trump’s telling, the whole city of Aurora being taken over by migrants carrying weapons of war.

”And getting them out will be a bloody story,” Mr. Trump said of Aurora at a rally in Mosinee, Wis., last Saturday, adding that it was “not going to be easy, but we’ll do it.”

Mr. Coffman and Ms. Jurinsky have both since backtracked.

“The overstated claims fueled by social media and through select news organizations are simply not true,” they wrote in a joint statement released Wednesday that appeared aimed at pushing back on Mr. Trump’s debate comments.

That culminated in a Trump rally on October 11. Miller served as Trump’s opening act, using posters of alleged TdA members (just like those Trump set up outside the White House the other day) to rile up the crowd.

Here’s how NYT’s Michael Gold and Jonathan Weisman described the rally, including their cautions about Trump’s reading of the AEA, something that didn’t make NYT’s opus yesterday.

Former President Donald J. Trump escalated the nativist, anti-immigration rhetoric that has animated his political career with a speech Friday in Aurora, Colo., where he repeated false and grossly exaggerated claims about undocumented immigrants that local Republican officials have refuted.

For weeks, Aurora has been fending off false rumors about the city. And its conservative Republican mayor, Mike Coffman, said in a statement on Friday that he hoped to show Mr. Trump that Aurora was “a considerably safe city.”

But Mr. Trump has made debunked claims about Aurora, a Denver suburb, such a central part of his stump speech that he took a campaign detour to Colorado, which has not voted for a Republican in a presidential election since 2004, to make the case in person at a rally at the Gaylord Rockies Resort & Convention Center.

And during a meandering 80-minute speech Mr. Trump repeated claims, which have been debunked by local officials, that Aurora had been “invaded and conquered,” described the United States as an “occupied state,” called for the death penalty “for any migrant that kills an American citizen” and revived a promise to use the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport suspected members of drug cartels and criminal gangs without due process.

That law allows for the summary deportation of people from nations with which the United States is at war, that have invaded the United States or that have engaged in “predatory incursions.” It was far from clear whether the law could be used in the way that Mr. Trump was proposing.

[snip]

The city put out a statement on Friday pre-emptively fact-checking the former president ahead of his rally.

“A gang has not ‘taken over’ the city,” it said. “The overstated claims fueled by social media and through select news organizations are simply not true. It is tragic that select individuals and entities have mischaracterized our city based on some specific incidents.”

Major crimes, it continued, are down more than 17 percent in Aurora. And “the city is actively deploying every legal tool to ensure CBZ Management is accountable for its properties and meets its responsibilities.”

After the rally, Mr. Coffman, the mayor, said that he was “disappointed that the former president did not get to experience more of our city for himself” and that “the reality is that the concerns about Venezuelan gang activity in our city — and our state — have been grossly exaggerated and have unfairly hurt the city’s identity and sense of safety.”

“The city and state have not been ‘taken over’ or ‘invaded’ or ‘occupied’ by migrant gangs,” he said. “The incidents that have occurred in Aurora, a city of 400,000 people, have been limited to a handful of specific apartment complexes, and our dedicated police officers have acted on those concerns and will continue to do so.” [my emphasis]

Weisman described the opposition from local politicians that same day.

Mike Coffman, the conservative Republican mayor of Aurora, Colo., had a message for former President Donald J. Trump before the Republican nominee for the White House came on Friday to a city he has repeatedly painted as having been taken over by vicious migrant street thugs.

The visit, Mr. Coffman said in a statement to The Times, “is an opportunity to show him and the nation that Aurora is a considerably safe city — not a city overrun by Venezuelan gangs. My public offer to show him our community and meet with our police chief for a briefing still stands.”

It is not a message likely to get through.

In the closing weeks of Mr. Trump’s campaign, his efforts to demonize immigrants, whether they are from Venezuela, Haiti or elsewhere, have gotten ever more lurid — and more impervious to the facts, even those provided by Republican allies such as Mr. Coffman. Last month, the former president began portraying Aurora, a sprawling suburb of Denver, population 404,219, as “a war zone” overrun by a violent Venezuelan street gang, Tren de Aragua.

Despite the entreaties of Aurora city officials in both parties to stay away, Mr. Trump took his case to Aurora itself on Friday. He was there for an afternoon rally at the Gaylord Rockies Resort & Convention Center, a location that is decidedly not overrun by Venezuelan gangs.

He is not welcome, declared Crystal Murillo, a Democratic city councilwoman and a Mexican American.

“My message is, Trump doesn’t belong here,” she said in an interview. “His divisiveness, his rhetoric, is not what Aurora is about.”

When Tim Walz and others called out the lies Trump was telling in real time, Miller accused them then (as he is now) of defending gang members.

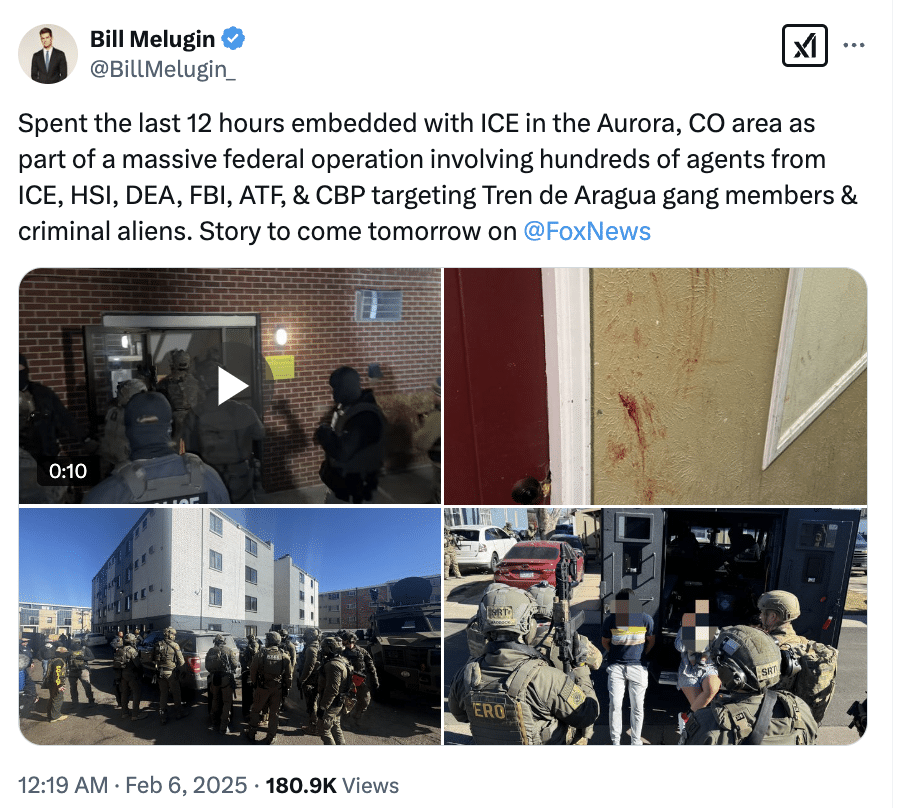

Even though the claims Trump made about Aurora during the campaign were built on exaggerations and lies, ICE did a high profile raid in the city early in Trump’s term, on February 6, with Fox News’ chief immigration propagandist Bill Melugin in tow.

The raid found only one TdA member.

On Thursday, shortly after the raid, the Fox News propagandist whose job it is to stoke fear about migration, Bill Melugin, first celebrated the “massive” raid, only later to reveal the raid had resulted in far fewer arrests than promised and just one arrest of a Tren de Aragua member. ICE immediately blamed its failure to detain more people on leaks.

That same day, Tom Homan announced he may have to halt the kind of embed ICE has been all too happy to give Melugin, because of leaks or operational security; he did not say that truthful reports to Fox viewers about his failures gets him in trouble with the boss. Tom Homan can’t afford to have Trump know that this massive raid found only a single Tren de Aragua member.

Kristi Noem blamed the failure to find numbers of TdA members that might substantiate Stephen Miller’s false claims about the gang on leakers. Tom Homan claimed to have identified the leakers on February 26, but they have not yet been charged.

In the wake of the raid that failed to substantiate the false claims and overblown promises he made during the election, Trump started bitching that ICE wasn’t meeting his promised deportation targets (they still aren’t, though they have shut down new migration). Tom Homan and Stephen Miller were failing to fulfill Trump’s top campaign promise, a promise built on Miller’s lies.

Agents at Immigration and Customs Enforcement are under increasing pressure to boost the number of arrests and deportations of undocumented immigrants, as President Donald Trump has expressed anger that the amount of people deported in the first weeks of his administration is not higher, according to three sources familiar with the discussions at ICE and the White House.

A source familiar with Trump’s thinking said the president is getting “angry” that more people are not being deported and that the message is being passed along to “border czar” Tom Homan, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller and acting ICE Director Caleb Vitello.

“It’s driving him nuts they’re not deporting more people,” said the person familiar with Trump’s thinking.

[snip]

Meanwhile at ICE, Vitello told agents in January to aim to meet a daily quota of 1,200-1,400 arrests. According to numbers ICE has posted on X, the highest single day total since Trump was inaugurated was just 1,100, and the number has fallen since that day. On Tuesday of this week, arrests of immigrants were over 800, according to a source familiar with the numbers. But last weekend, there were only about 300 arrests, another source told NBC News.

In order to fulfill Trump’s Inauguration Day promise of “millions and millions” of deportations, the Trump administration would have to be deporting over 2,700 immigrants every day to reach 1 million in a year.

And, as NBC News has reported, arrests do not always equal immediate detentions, much less deportations. Of the more than 8,000 immigrants arrested in the first two weeks of the Trump administration, 461 were released, according to the White House.

Later that month, on February 26 (the same day Homan claimed to have found the leakers), the Intelligence Committee did an assessment of the relationship between TdA and Nicolás Maduro’s government. Only the FBI believed there was a tie.

The intelligence community assessment concluded that the gang, Tren de Aragua, was not directed by Venezuela’s government or committing crimes in the United States on its orders, according to the officials, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations.

Analysts put that conclusion at a “moderate” confidence level, the officials said, because of a limited volume of available reporting about the gang. Most of the intelligence community, including the C.I.A. and the National Security Agency, agreed with that assessment.

Only one agency, the F.B.I., partly dissented. It maintained the gang has a connection to the administration of Venezuela’s authoritarian president, Nicolás Maduro, based on information the other agencies did not find credible.

“Multiple intelligence assessments are prepared on issues for a variety of reasons,” the White House said in a statement. “The president was well within his legal and constitutional authority to invoke the Alien Enemies Act to expel illegal foreign terrorists from our country.”

This NYT story is one of only two stories that Pam Bondi claimed to include classified information when she reversed protections on journalists (the other was this April 17 WaPo story reporting that a more formal National Intelligence Estimate also debunked the claim of ties between Maduro and TdA). Bondi wants to find the people who debunked this false claim, and she’s willing to use subpoenas to journalists or even warrants targeting them to do so.

NYT’s story yesterday described this assessment retrospectively — as something that led bureaucrats at State to grow concerned about their reliance on it.

During an internal State Department briefing about issues related to Latin America, some employees were dismayed to hear that weeks earlier, American spy agencies had assessed that Tren de Aragua was not actually controlled by the Venezuelan government — which was the premise for invoking the Alien Enemies Act.

What NYT couldn’t fit into a 4,000-word article is that this assessment preceded Trump’s AEA declaration — in which the asserted tie between TdA and Maduro was legally central — by more than two weeks.

Tren de Aragua (TdA) is a designated Foreign Terrorist Organization with thousands of members, many of whom have unlawfully infiltrated the United States and are conducting irregular warfare and undertaking hostile actions against the United States. TdA operates in conjunction with Cártel de los Soles, the Nicolas Maduro regime-sponsored, narco-terrorism enterprise based in Venezuela, and commits brutal crimes, including murders, kidnappings, extortions, and human, drug, and weapons trafficking. TdA has engaged in and continues to engage in mass illegal migration to the United States to further its objectives of harming United States citizens, undermining public safety, and supporting the Maduro regime’s goal of destabilizing democratic nations in the Americas, including the United States.

TdA is closely aligned with, and indeed has infiltrated, the Maduro regime, including its military and law enforcement apparatus. TdA grew significantly while Tareck El Aissami served as governor of Aragua between 2012 and 2017. In 2017, El Aissami was appointed as Vice President of Venezuela. Soon thereafter, the United States Department of the Treasury designated El Aissami as a Specially Designated Narcotics Trafficker under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, 21 U.S.C. 1901 et seq. El Aissami is currently a United States fugitive facing charges arising from his violations of United States sanctions triggered by his Department of the Treasury designation.

Like El Aissami, Nicolas Maduro, who claims to act as Venezuela’s President and asserts control over the security forces and other authorities in Venezuela, also maintains close ties to regime-sponsored narco-terrorists. Maduro leads the regime-sponsored enterprise Cártel de los Soles, which coordinates with and relies on TdA and other organizations to carry out its objective of using illegal narcotics as a weapon to “flood” the United States. In 2020, Maduro and other regime members were charged with narcoterrorism and other crimes in connection with this plot against America.

Over the years, Venezuelan national and local authorities have ceded ever-greater control over their territories to transnational criminal organizations, including TdA. The result is a hybrid criminal state that is perpetrating an invasion of and predatory incursion into the United States, and which poses a substantial danger to the United States. Indeed, in December 2024, INTERPOL Washington confirmed: “Tren de Aragua has emerged as a significant threat to the United States as it infiltrates migration flows from Venezuela.” Evidence irrefutably demonstrates that TdA has invaded the United States and continues to invade, attempt to invade, and threaten to invade the country; perpetrated irregular warfare within the country; and used drug trafficking as a weapon against our citizens. [my emphasis]

That is, Trump knew or should have known, when he made this invocation, it was based on claims his own IC would not substantiate. Only the agency run by Kash Patel would back that claim.

Trump made this invocation, per the NYT story, the same day that Trump finalized a deal with Nayib Bukele (NYT describes elsewhere the MS-13 members to whom Bukele did have a tie, that seem to have been included in the deal, but not here), and previewed its use in a presser at DOJ watched over by Stephen Miller.

On March 14, the Trump administration exchanged diplomatic notes with El Salvador laying out the terms: Mr. Bukele’s government would receive up to 300 members of Tren de Aragua in exchange for financial support from the United States.

That same day, Mr. Trump hinted at the forthcoming deportations during a speech at the Justice Department. Sitting in the front of the audience was Mr. Miller, who had moments earlier conferred with Todd Blanche, the deputy attorney general, about the pending deportations.

“We’ve caught hundreds of them, the Venezuelan gang, which is as bad as it gets,” Mr. Trump told a crowd of loyalists. “And you’ll be reading a lot of stories tomorrow about what we’ve done with them and you’ll be very impressed.”

That’s what triggered a hasty effort to put bodies on planes, a process riddled with error.

That presser is also what led ACLU to try to preempt precisely this AEA invocation, to successfully obtain an order enjoining deportations relying on Trump’s TdA AEA declaration, even as planes were departing enjoining such flights.

The President has invoked—or will imminently invoke—a war power, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 (“AEA”), in an attempt to summarily remove noncitizens from the United States and bypass the immigration laws Congress has enacted. 1 In either circumstance, a Temporary Restraining Order is needed because there may not be sufficient time for this Court to intervene between the time when the Act is invoked and when the planes removing Plaintiffs-Petitioners depart the United States. 2

But the United States is not at war, and the prerequisites for invocation of the AEA have not been met. See 50 U.S.C. § 21. The President can invoke the AEA only in a state of “declared war,” or when an “invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government.” Id. Not surprisingly, therefore, the Act has been invoked only three times in our country’s history, all in declared wars: The War of 1812, World War I, and World War II.

The President’s imminent Proclamation targets Venezuelan noncitizens whom the government accuses of being part of Tren de Aragua, a criminal gang. But the President’s Proclamation is invalid under the AEA for two plain reasons. First, Tren de Aragua is not a “foreign nation or government.” Second, Tren de Aragua is not engaged in an “invasion” or “predatory incursions” within the meaning of the AEA, because criminal activity does not meet the longstanding definitions of those statutory requirements—and has never been a sufficient basis for the executive to cast foreign nationals as “alien enemies” subject to arrest, internment, and removal. As a result, the President’s attempt to summarily remove Venezuelan noncitizens exceeds the wartime authority that Congress delegated in the AEA, violates the process and protections that Congress has prescribed elsewhere in the country’s immigration laws for the removal of noncitizens, and violates due process.

Based on reports from Plaintiffs and legal service providers, the government has begun moving Venezuelan men who the government claims are part of Tren de Aragua to facilities in Texas.

1 See Remarks of President Trump, March 14, 2025 (addressing the Department of Justice) (“You will read in the papers tomorrow the bad thing we will do to Tren de Aragua.”).

2 See also Priscilla Alvarez, et al., Trump expected to invoke wartime authority to speed up mass deportation effort in coming days, CNN (Mar. 14, 2025), https://www.cnn.com/2025/03/13/politics/alien-enemies-act-deportationconsideration/index.html (“The Trump administration is expected to invoke [the AEA] to speed up the president’s mass deportation pledge in the coming days, according to four sources familiar with the discussions. . . . The primary target remains Tren de Aragua[.]”).

As described in this NYT story (and earlier ones), unnamed senior officials in the White House discussed whether to obey this order or not.

Inside the White House, senior administration officials quickly discussed the order and whether they should move ahead. The team of Trump advisers decided to go forward, believing the planes were safely in international airspace, and well aware that the legal fight was most likely destined for the Supreme Court, where conservatives have a majority.

At 7:36 p.m., the third flight took off. Officials would later say the migrants on that flight were not deported under the Alien Enemies Act, but through regular immigration proceedings.

The White House’s decision to press forward, despite Judge Boasberg’s order, raised questions about whether the administration was defying the court. The Justice Department has argued that a federal judge cannot dictate foreign policy.

No one is saying it, but there are a lot of breadcrumbs in this article and others that Miller was one of those SAOs who instructed that the flights should go even in spite of Judge Boasberg’s order. One big breadcrumb is that, as the story describes, even before inauguration, Miller told others not to worry about legal challenges to the means via which Trump planned to deport migrants, challenges like the one before Boasberg that, in real time, these SAOs assumed SCOTUS would make go away.

Stephen Miller, the main architect of Mr. Trump’s domestic agenda, had a message for other advisers inside the presidential transition offices in West Palm Beach, Fla.: Be bold. Do not worry about potential litigation, especially when drafting Mr. Trump’s immigration actions.

It was roughly a month before the inauguration, and Mr. Miller knew he needed to move fast to make good on Mr. Trump’s campaign pledge of mass deportations.

The Administration has invented flimsy excuses for why the planes flew in spite of Boasberg’s order, precisely the claimed belief that NYT accepts unquestionably, that the planes were in international airspace (NYT are more skeptical, as am I, that the third included only men against whom DHS had already obtained deportation orders). In finding probable cause that, “the Government’s actions on that day demonstrate a willful disregard for its Order, sufficient for the Court to conclude that probable cause exists to find the Government in criminal contempt,” Judge Boasberg was far less impressed with these excuses than the NYT.

As this was blowing up in the wake of Boasberg’s order, per the stories, Bukele asked for cover for the people delivered to his custody, for proof they were who Trump had said they were.

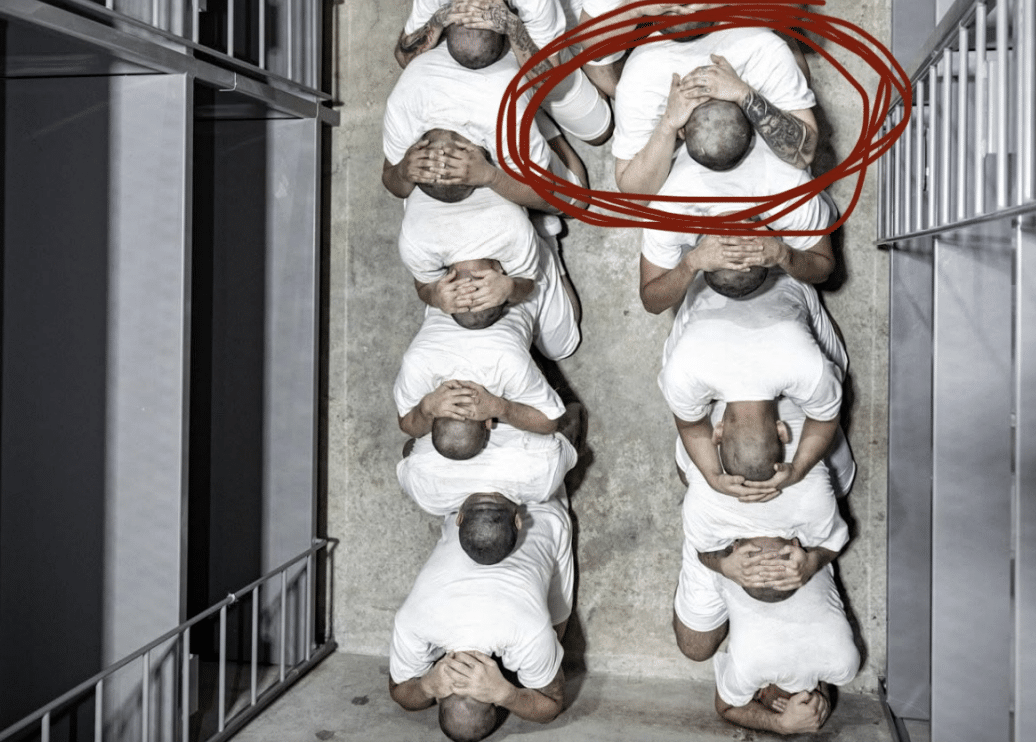

[W]eeks earlier, when the three planes of deportees landed, it was the Salvadoran president who had quietly expressed concerns.

As part of the agreement with the Trump administration, Mr. Bukele had agreed to house only what he called “convicted criminals” in the prison. However, many of the Venezuelan men labeled gang members and terrorists by the U.S. government had not been tried in court.

Mr. Bukele wanted assurances from the United States that each of those locked up in the prison was members of Tren de Aragua, the transnational gang with roots in Venezuela, according to people familiar with the situation and documents obtained by The New York Times.

The matter was urgent, a senior U.S. official warned his colleagues shortly after the deportations, kicking off a scramble to get the Salvadorans whatever evidence they could.

Mr. Bukele’s demands for more information about some of the deportees, which has not been previously reported, deepen questions about whether the Trump administration sufficiently assessed who it dispatched to a foreign prison. [my emphasis]

Something has been misunderstood about this passage, which describes Bukele’s concerns as retrospective (though he did reject Venezuelan women — which NYT notes — and one Nicaraguan — which it does not, and which debunks their claim that Bukele was willing to accept detainees of any nationality — in real time). Bukele asked for proof these people were criminals as this was all blowing up. By deciding to send the planes in defiance of Judge Boasberg’s order, Trump created problems for Bukele, problems that their utter failure to vet any of these people — their decision to let flimsy lies stand in for evidence — exacerbated.

Within a week, Trump was disavowing having signed the AEA proclamation relying on claims that his Intelligence Community had debunked weeks earlier.

President Donald Trump on Friday downplayed his involvement in invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport Venezuelan migrants, saying for the first time that he hadn’t signed the proclamation, even as he stood by his administration’s move.

“I don’t know when it was signed, because I didn’t sign it,” Trump told reporters before leaving the White House on Friday evening.

The president made his comments when asked to respond to Judge James Boasberg’s concerns in court on Friday that the proclamation was “signed in the dark” of night and that migrants were hurried onto planes.

“We want to get criminals out of our country, number one, and I don’t know when it was signed, because I didn’t sign it,” Trump said. “Other people handled it, but (Secretary of State) Marco Rubio has done a great job and he wanted them out and we go along with that. We want to get criminals out of our country.”

But when the conservative majority he banked on ruling for him twice did not, first ruling that detainees had to have an opportunity to challenge their deportation under habeas corpus, and then ruling that Trump had to “facilitate” Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s return, Miller blatantly lied at the Bukele Oval Office presser about what SCOTUS said, followed by a colloquy in which Trump got him to repeat his bullshit claims.

[T]here’s an illegal alien from El Salvador. So with respect to you, he’s a citizen of El Salvador. So it’s very arrogant, even for American media to suggest that we would even tell El Salvador how to handle their own citizens as a starting point, as two immigration courts found that he was a member of MS-13. When President Trump declared MS-13 to be a foreign terrorist organization, that meant that he was no longer eligible under federal law, which I’m sure you know, you’re very familiar with the INA, that he was no longer eligible for any form of immigration relief in the United States.

So he had a deportation order that was valid. Which meant that under our law, he’s not even allowed to be present in the United States and had to be returned because of the foreign terrorist designation. This issue was then, by a district court judge, completely inverted, and a district court judge tried to tell the administration that they had to kidnap a citizen of El Salvador and flying back here. That issue was raised with the Supreme Court.

And the Supreme Court said the District court order was unlawful and its main components were reversed 9-0 unanimously stating clearly that neither Secretary of State nor the President could be compelled by anybody to forcibly retrieve a citizen of El Salvador from El Salvador, who again is a member of MS-13. Which is, I’m sure you understand, rapes little girls, murders women, murders children, is engaged in the most barbaric activities in the world. And I can promise you, if he was your neighbor, you would move right away.

REPORTERS: So you don’t plan to ask for-

But the Supreme Court is asking to-

Donald Trump: And what was the ruling in the Supreme Court, Steve? Was it nine to nothing?

Steve Miller: Yes. It was a 9- 0-

Donald Trump: In our favor?

Steve Miller: In our favor against the District Court. Ruling saying that no district court has the power to compel the foreign policy function of the United States. As Pam said, the ruling solely stated that if this individual, at El Salvador’s sole discretion, was sent back to our country, that we could deport him a second time.

No version of this legally ends up with him ever living here because he’s a citizen of El Salvador. That is the president of El Salvador. Your questions about it per the court can only be directed to him.

It’s not just that Trump had Miller perform this for the press and Bukele. He also performed himself taking Miller’s false claims about what SCOTUS said as word, even as he continues to insist unnamed lawyers provide him legal advice that informs his own actions. This was Trump laying out his own plausible deniability in real time. It’s not his fault he continued to defy SCOTUS. He’s just getting demonstrably erroneous advice, from the guy who orchestrated this entire ploy years in advance, orchestrated the propaganda to justify the focus on TdA, and seemingly orchestrated the problematic AEA invocation as well.

It’s not Donald Trump’s fault.

It’s Miller’s, the gatekeeper who prevents any contrary information to make it to Trump.

And that’s the background to the second story describing how, in a week during which DOJ bought time, someone performed asking Bukele to send Abrego Garcia back and Bukele performed refusing to do so.

The Trump administration recently sent a diplomatic note to officials in El Salvador to inquire about releasing a Salvadoran immigrant whom government officials have been ordered by the Supreme Court to help free, according to three people with knowledge of the matter.

But the authoritarian government of Nayib Bukele, the leader of El Salvador, said no, two of the people said. The Bukele administration claimed the man should stay in El Salvador because he was a Salvadoran citizen, according to one of those people.

It remained unclear whether the diplomatic effort was a genuine bid by the White House to address the plight of the immigrant, Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, whom administration officials have repeatedly acknowledged was improperly expelled to El Salvador last month in violation of a court order expressly prohibiting him from being sent there.

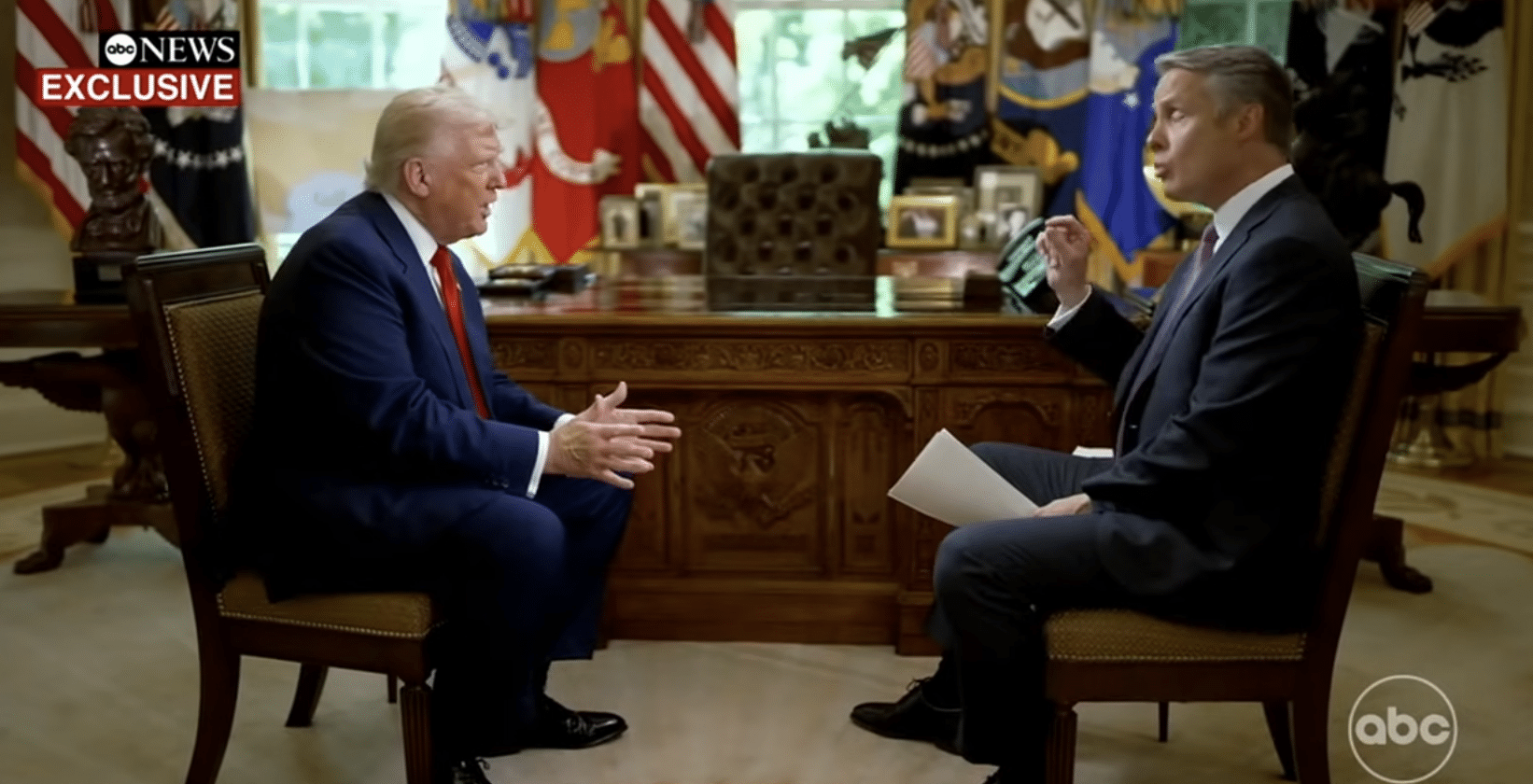

NYT describes that their scoop came after Trump blew all this up in his ABC interview.

The revelation came just hours after the president, reversing course on his administration’s previous statements, said in an interview with ABC News that he had the ability to bring Mr. Abrego Garcia back. The president added that he did not believe Mr. Abrego Garcia was a good person and that his administration’s lawyers would decide. The Justice Department is also facing a court-ordered deadline of early next week to provide information about what it has done to seek his freedom.

This was certainly published after Trump’s comments. Is NYT really saying that this entire story came together in the wake of ABC’s interview (or airing thereof)?

Whatever the case, these details — and Judge Paula Xinis’ renewed discovery order — explain the stakes of the twin exchanges between Trump and Terry Moran the other day.

When Trump demanded Moran adopt his false claims about Abrego Garcia’s knuckles, he did so because Stephen Miller has left him politically exposed (though not legally, thanks to SCOTUS’ immunity order last year, which may explain why Trump is so openly defiant). Trump has to affirm Miller’s lies and his belief in them, just as he tripled down on his election lies as it became a criminal problem, because otherwise he has the kind of guilty consciousness and foreknowledge that could become a problem down the road.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Wait a minute.

TERRY MORAN: I want —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Hey, Terry. Terry. Terry.

TERRY MORAN: He — he did not have the letter —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Don’t do that — M-S-1-3 — It says M-S-one-three.

TERRY MORAN: I — that was Photoshop. So let me just–

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: That was Photoshop? Terry, you can’t do that — he had —

— he– hey, they’re givin’ you the big break of a lifetime. You know, you’re doin’ the interview. I picked you because — frankly I never heard of you, but that’s okay —

TERRY MORAN: This — I knew this would come —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: But I picked you — Terry — but you’re not being very nice. He had MS-13 tattooed —

TERRY MORAN: Alright. Alright. We’ll agree to disagree. I want to move on —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Terry.

TERRY MORAN: — to something else.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Terry. Do you want me to show the picture?

TERRY MORAN: I saw the picture. We’ll — we’ll — we’ll agree to disagree —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Oh, and you think it was Photoshop. Well —

TERRY MORAN: Here we go. Here we go.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: — don’t Photoshop it. Go look —

TERRY MORAN: Alright.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: — at his hand. He had MS-13 —

TERRY MORAN: Fair enough, he did have tattoos that can be interpreted that way. I’m not an expert on them.

I want to turn to Ukraine, sir —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: No, no. Terry —

TERRY MORAN: I– I want to get to Ukraine–

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Terry, no, no. No, no. He had MS as clear as you can be. Not “interpreted.” This is why people —

And when Trump grew hostile after Moran cornered him into admitting that, yes, he had the power to get Abrego Garcia returned, Trump needed to reinforce the plausible deniability he started building as soon as this thing started going to shit.

TERRY MORAN: I’m not saying he’s a good guy. It’s about the rule of law. The order from the Supreme Court stands, sir —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: He came into our country illegally.

TERRY MORAN: You could get him back. There’s a phone on this desk.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: I could.

TERRY MORAN: You could pick it up, and with all —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: I could

TERRY MORAN: — the power of the presidency, you could call up the president of El Salvador and say, “Send him back,” right now.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: And if he were the gentleman that you say he is, I would do that.

TERRY MORAN: But the court has ordered you —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: But he’s not.

TERRY MORAN: — to facilitate that — his release–

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: I’m not the one making this decision. We have lawyers that don’t want —

TERRY MORAN: You’re the president.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: — to do this, Terry —

TERRY MORAN: Yeah, but the — but the buck stops in this office —

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: I — no, no, no, no. I follow the law. You want me to follow the law. If I were the president that just wanted to do anything, I’d probably keep him right where he is —

TERRY MORAN: The Supreme Court says what the law is. [my emphasis]

Sure, the buck stops here. Trump is all powerful. But he — the President — is not making the decisions, did not make the AEA invocation based on lies. “The lawyers” did that. And they don’t want him to pick up that phone and facilitate Abrego Garcia’s return.

There’s no sign that Trump and Stephen Miller plan to give up this campaign, even as conservative Catholic SCOTUS justices break their Easter weekend observances to prevent Trump from pulling this trick a second time, a third adverse ruling. Instead, Stephen Miller will instead target the judges who tell him he (who is not a lawyer) has gotten the law wrong, over and over.

And that will force Trump to continue to insist that journalists affirm whatever Stephen Miller tells him is true.

Update: Trump appointed Judge Fernando Rodriguez, Jr. just ruled that Trump’s invocation of the AEA is unlawful and will move to relieve three plaintiffs held under it.

Those factual statements depict conduct by TdA that unambiguously is harmful to society in this country. And as previously explained, the political question doctrine prohibits the Court from weighing the truth of those factual statements, including whether Maduro directs TdA’s actions or the extent of the referenced criminal activity.

Instead, the Court determines whether the factual statements in the Proclamation, taken as true, describe an “invasion” or “predatory incursion” for purposes of the AEA. Based on the plain, ordinary meaning of those terms in the late 1790’s, the Court concludes that the factual statements do not. The Proclamation makes no reference to and in no manner suggests that a threat exists of an organized, armed group of individuals entering the United States at the direction of Venezuela to conquer the country or assume control over a portion of the nation. Thus, the Proclamation’s language cannot be read as describing conduct that falls within the meaning of “invasion” for purposes of the AEA. As for “predatory incursion,” the Proclamation does not describe an armed group of individuals entering the United States as an organized unit to attack a city, coastal town, or other defined geographical area, with the purpose of plundering or destroying property and lives. While the Proclamation references that TdA members have harmed lives in the United States and engage in crime, the Proclamation does not suggest that they have done so through an organized armed attack, or that Venezuela has threatened or attempted such an attack through TdA members. As a result, the Proclamation also falls short of describing a “predatory incursion” as that concept was understood at the time of the AEA’s enactment.11

For these reasons, the Court concludes that the President’s invocation of the AEA through the Proclamation exceeds the scope of the statute and, as a result, is unlawful. Respondents do not possess the lawful authority under the AEA, and based on the Proclamation, to detain Venezuelan aliens, transfer them within the United States, or remove them from the country.

Just before he did that, he certified class status to similarly situated people in SDTX.