Four Data Points on the January 6 Insurrection

The NYT and WaPo both have stories beginning to explain the failures to protect the Capitol (ProPublica had a really good one days ago). The core issue, thus far, concerns DOD’s delays before sending in the National Guard — something that they happened to incorporate into a timeline not long after the attack, before the Capitol Police or City of DC had put their own together (the timeline has some gaps).

I can think of two charitable explanations for the lapses. First, in the wake of criticism over the deployment of military resources and tear gas against peaceful protestors to protect Donald Trump in June, those who had been criticized were reluctant to repeat such a display of force to protect Congress (and Mike Pence). In addition, in both DOJ and FBI under the Trump Administration, job security and career advancement depended on reinforcing the President’s false claims that his political supporters had been unfairly spied on, which undoubtedly created a predictable reluctance to treat those political supporters as the urgent national security threat they are and have always been.

Those are just the most charitable explanations I can think of, though. Both are barely distinguishable from a deliberate attempt to punish the President’s opponents — including Muriel Bowser and Nancy Pelosi — for their past criticism of Trump’s militarization of the police and an overt politicization of law enforcement. Or, even worse, a plan to exploit these past events to create the opportunity for a coup to succeed.

We won’t know which of these possible explanations it is (likely, there are a range of explanations), and won’t know for many months.

That said, I want to look at a few data points that may provide useful background.

Trump plans to pardon those in the bunker

First, as I noted here, according to Bloomberg, Trump has talked about pardoning the four men who’ve been in the bunker with Trump plotting recent events, along with Rudy Giuliani, who is also likely to be pardoned.

Preemptive pardons are under discussion for top White House officials who have not been charged with crimes, including Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, senior adviser Stephen Miller, personnel chief John McEntee, and social media director Dan Scavino.

I like to think I’ve got a pretty good sense of potential legal exposure Trump’s flunkies have, yet I know of nothing (aside, perhaps, from McEntee’s gambling problems) that these men have clear criminal liability in. And yet Trump seems to believe these men — including the guy with close ties to far right Congressmen, the white nationalist, the guy who remade several agencies to ensure that only loyalists remained in key positions, and the guy who tweets out Trump’s barely-coded dogwhistles — need a pardon.

That may suggest that they engaged in sufficient affirmative plotting even before Wednesday’s events.

Mind you, if these men had a role in coordinating all this, a pardon might backfire, as it would free them up to testify about any role Trump had in planning what happened on Wednesday.

Trump rewards Devin Nunes for helping him to avoid accountability

Several key questions going forward will focus on whether incompetence or worse led top officials at DOD to limit the mandate for the National Guard on January 6 and, as both DC and the Capitol Police desperately called for reinforcements, stalled before sending them.

A key player in that question is Kash Patel, who served as a gatekeeper at HPSCI to ensure that Republicans got a distorted view of the Russian intelligence implicating Trump, then moved to the White House to ensure that Trump got his Ukraine intelligence via Patel rather than people who knew anything about the topic, and then got moved to DOD to oversee a takeover of the Pentagon by people fiercely loyal to Trump.

And a key player in coordinating Kash’s activities was his original boss, Devin Nunes. On Monday, Trump gave Nunes the Medal of Freedom, basically the equivalent of a pardon to someone who likely believes his actions have all been protected by speech and debate. The entire citation for the award is an expression of the steps by which Trump, with Nunes’ help, undermined legitimate investigations into himself. In particular, Trump cited how Nunes’ efforts had hollowed out the FBI of people who might investigate anyone loyal to Trump.

Devin Nunes’ courageous actions helped thwart a plot to take down a sitting United States president. Devin’s efforts led to the firing, demotion, or resignation of over a dozen FBI and DOJ employees. He also forced the disclosure of documents that proved that a corrupt senior FBI official pursued a vindictive persecution of General Michael Flynn — even after rank and file FBI agents found no evidence of wrongdoing.

Congressman Nunes pursued the Russia Hoax at great personal risk and never stopped standing up for the truth. He had the fortitude to take on the media, the FBI, the Intelligence Community, the Democrat Party, foreign spies, and the full power of the Deep State. Devin paid a price for his courage. The media smeared him and liberal activists opened a frivolous and unjustified ethics investigation, dragging his name through the mud for eight long months. Two dozen members of his family received threatening phone calls – including his 98 year old grandmother.

Whatever else this debasement of the nation’s highest award for civilians might have done, it signaled to Nunes’ team — including but not limited to Patel — Trump’s appreciation for their work, and rewarded the guy he credits with politicizing the FBI.

That politicization is, as I noted above, one of the more charitable explanations for the FBI’s lack of preparation on Wednesday.

Interestingly, Nunes is not one of the members of Congress who challenged Biden’s votes after law enforcement restored order.

Corrected: Nunes did object to both AZ and PA.

Trump takes steps to designate Antifa as a Foreign Terrorist Organization

The day before the insurrection, Trump signed an Executive Order excluding immigrants if they have any tie to Antifa. Effectively, it put Antifa on the same kind of exclusionary footing as Communists or ISIS terrorists. Had Trump signed the EO before he was on his way out the door, it would have initiated a process likely to end with Antifa listed as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, giving the Intelligence Community additional intelligence tools to track members of the organization, even in the United States (the kind of tools, not coincidentally, that some experts say the FBI needs against white supremacist terrorists).

The EO will have next to no effect. Joe Biden will rescind it among the other trash he needs to clean up in the early days of his Administration.

But I find it curious that Trump effectively named a domestic movement a terrorist organization just days before multiple Trump associates attempted to blame Antifa for the riot at the Capitol.

That effort actually started before the order was signed. Back in December, Enrique Tarrio suggested that the Proud Boys (a group Trump had called to “Stand by” in September) might wear all black — a costume for Antifa — as they protested.

“The ProudBoys will turn out in record numbers on Jan 6th but this time with a twist…,” Henry “Enrique” Tarrio, the group’s president, wrote in a late-December post on Parler, a social media platform that has become popular with right-wing activists and conservatives. “We will not be wearing our traditional Black and Yellow. We will be incognito and we will spread across downtown DC in smaller teams. And who knows….we might dress in all BLACK for the occasion.”

The day after the riot, Matt Gaetz relied on a since-deleted Washington Times post to claim that the riot was a false flag launched by Antifa.

In a speech during the process of certifying President-elect Joe Biden, Gaetz claimed there was “some pretty compelling evidence from a facial recognition company” that some Capitol rioters were actually “members of the violent terrorist group antifa.” (Antifa is not a single defined group, does not have an official membership, and has not been designated a terrorist organization, although President Donald Trump has described it as one.)

Gaetz attributed this claim to a short Washington Times article published yesterday. That article, in turn, cited a “retired military officer.” The officer asserted that a company called XRVision “used its software to do facial recognition of protesters and matched two Philadelphia antifa members to two men inside the Senate.” The Times said it had been given a copy of the photo match, but it didn’t publish the picture.

There is no evidence to support the Times’ article, however. An XRVision spokesperson linked The Verge to a blog post by CTO Yaacov Apelbaum, denying its claims and calling the story “outright false, misleading, and defamatory.” (Speech delivered during congressional debate, such as Gaetz’s, is protected from defamation claims.) The Times article was apparently deleted a few hours after Apelbaum’s post.

Rudy Giuliani also attempted to blame Antifa.

And Captain Emily Rainey, who resigned today as DOD investigates the PsyOp officer for her role in the insurgency, also blamed Antifa for the violence.

Her group — as well as most at Wednesday’s rally — were “peace-loving, law-abiding people who were doing nothing but demonstrating our First Amendment rights,” she said.

She even shared a video on Facebook insisting that the rioters were all Antifa, saying, “I don’t know any violent Patriots. I don’t know any Patriots who would smash the windows of a National jewel like the [Capitol].”

It is entirely predictable that Trump loyalists would blame Antifa for anything bad they do — Bill Barr did so as the formal policy of DOJ going back at least a year. But Trump seems to have prepared the ground for such predictable scapegoating by taking steps to declare Antifa a terrorist “organization” hours before a riot led by his supporters would storm the Capitol.

The White House makes DHS Secretary Chad Wolf’s appointment especially illegal

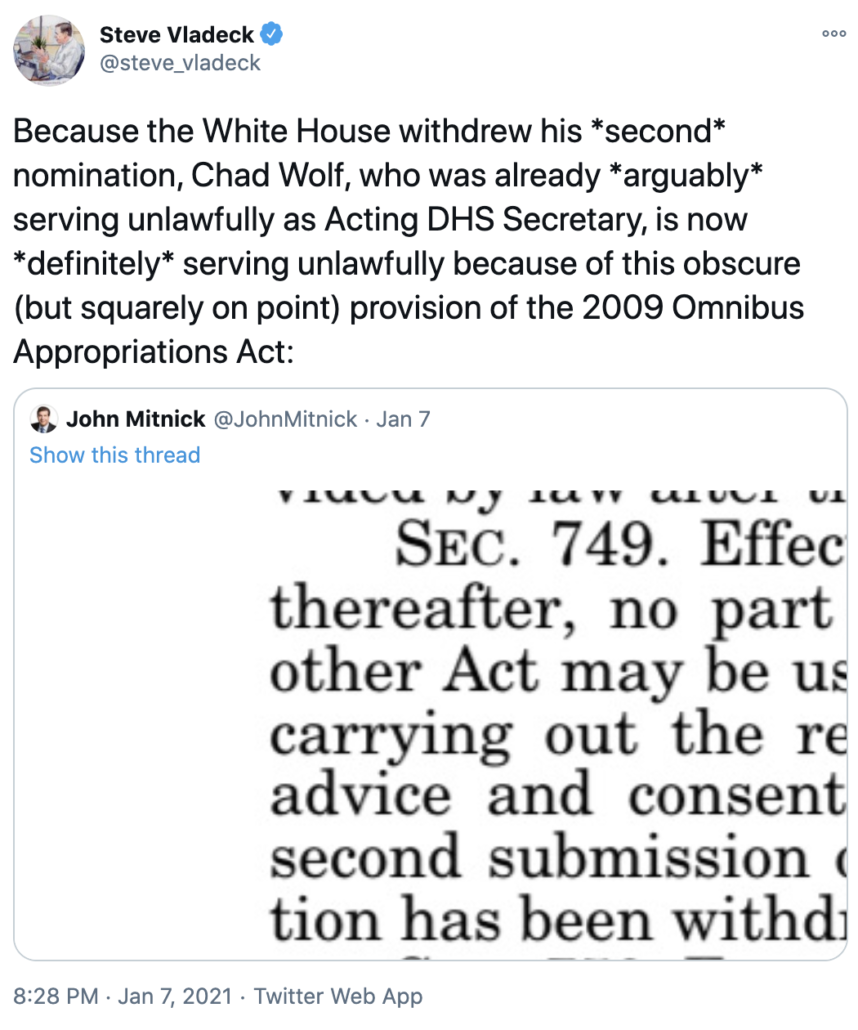

I’m most intrigued by a flip-flop that had the effect of making DHS Acting Secretary’s appointment even more illegal than it has already been at times in the last two years.

On January 3, the White House submitted Chad Wolf’s nomination, along with those of 29 other people, to be DHS Secretary. Then, on January 6, it withdrew the nomination.

Wolf himself was out of the country in Bahrain when the riot happened. But he did tweet out — before DOD mobilized the Guard — that DHS officials were supporting the counter-insurgency. And he issued both a tweet and then — the next day — a more formal statement condemning the violence.

It’s not entirely clear what happened between his renomination and the withdrawal, but Steve Vladeck (who tracks this stuff more closely than anyone), had a lot to say about the juggling, not least that the withdrawal of his resubmitted nomination made it very clear that Wolf is not now legally serving.

This could have had — and could have, going forward — a chilling effect on any orders Wolf issues to deploy law enforcement.

Thus far, we haven’t seen much about what DHS did and did not do in advance of the riot — though its maligned intelligence unit did not issue a bulletin warning of the danger.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation and an intelligence unit inside the Department of Homeland Security didn’t issue a threat assessment of the Jan. 6 pro-Trump protests that devolved into violence inside the Capitol, people briefed on the matter said.

In the weeks leading up to the protests, extremists posted about their plans to “storm” the Capitol on social media.

The joint department bulletin is a routine report before notable events that the agencies usually send to federal, state and local law-enforcement and homeland security advisers. The reports help plan for events that could pose significant risks.

At the DHS unit, called Intelligence and Analysis, management didn’t view the demonstrations as posing a significant threat, some of the people said.

Last year, Ken Cuccinelli forced whistleblower Brian Murphy to change language in a threat analysis to downplay white supremacist violence and instead blame Antifa and related groups.

In May 2020, Mr. Glawe retired, and Mr. Murphy assumed the role of Acting Under Secretary. In May 2020 and June 2020, Mr. Murphy had several meetings with Mr. Cuccinelli regarding the status of the HTA. Mr. Cuccinelli stated that Mr. Murphy needed to specifically modify the section on White Supremacy in a manner that made the threat appear less severe, as well as include information on the prominence of violent “left-wing” groups. Mr. Murphy declined to make the requested modifications, and informed Mr. Cuccinelli that it would constitute censorship of analysis and the improper administration of an intelligence program.

Wolf had been complicit in that past politicization. But something happened this week to lead the Trump White House to ensure that his orders can be legally challenged.

Update: Jake Gibson just reported that Wolf is stepping down.

These are just data points. We’ll learn far more about Trump’s involvement as the FBI obtains warrants for the communications who have ties to both groups like the Proud Boys and Trump associates like Roger Stone and Steve Bannon. But these are a few data points worth keeping an eye on.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)