OATH KEEPER SEDITIOUS CONSPIRACY CONVICTIONS WERE THE BATTLE; APPEALS MAY BE WAR

From emptywheel: Thanks to past support from readers, we can bring you Brandi’s preview of sedition appeals. To support Brandi’s larger book project on sedition, you can donate at the link here.

With the Oath Keepers’ historic seditious conspiracy trials now in the rearview, a new fight with significant implications is on the horizon. Almost all of the defendants—including and perhaps most unsurprisingly of all, Oath Keeper founder Elmer Stewart Rhodes are appealing their convictions.

Between two respective Oath Keeper trials involving seditious conspiracy that played out late last year and early into this one, prosecutors and defense attorneys spent an excess of 16 weeks duking it out in court, poring over mountains of evidence and examining dozens of witnesses including cooperating Oath Keepers. The Proud Boys seditious conspiracy trial stretched for more than 60 days and with verdicts reached in May, sentencing is expected in late August and early September.

It is often repeated and rightfully so: seditious conspiracy is one of the gravest charges that can be brought in the U.S., and it is very rarely prosecuted. When it is, it is not often a successful endeavor. The bar is high and narrow given that the line between First Amendment-protected activities and sedition can be razor-thin.

The U.S. has endured major setbacks in prosecuting sedition cases before, so with two sets of juries delivering guilty verdicts on this count for most of the Oath Keepers indicted on it, (and then later for the Proud Boys), these were huge victories for the Justice Department.

Huge but tempered.

Tempered because a conviction can also merely mark the end of one chapter and the start of another very tricky one once appeals are in the mix.

In a recent interview with NPR analyzing the Oath Keepers sedition verdicts, extremism expert and author Kathleen Belew pointed out that seditious conspiracy prosecutions can be a useful tool to combat extremist violence in society. She argues that it sends the message to extremist and militia groups, or other groups who use force as a movement, that they won’t be treated with kid gloves or prosecuted as lone actors. The risk of prosecuting extremists includes violent retaliation but as Belew also noted, these same prosecutions have the power to rouse people to the realization that their conduct is risky and potentially quite expensive to cope with legally.

Perhaps most eloquently, Belew underlined that the only way to tamp down on extremism is to confront it, not look away from it.

Recently, a report by The Washington Post suggested none of the sedition charges may have even come to pass if a reported skittishness to bring them had persisted at upper levels of the Justice Department at the outset of the Jan. 6 investigations. To read it, it would seem that many felt sedition was a bridge much too far or too risky politically. Marcy picked that WaPo report apart already and exposed key gaps and blind spots in the story so I won’t belabor those points here.

I will, however, belabor others.

First, Marcy’s unwinding of the Post story isn’t just context for context’s sake nor is it to browbeat a reporter like Carol Leonnig who is esteemed for good reason. (I have a lot of respect for her work and that of others at the Post, for the record). But Marcy does provide useful context by raising questions that, it would appear, the Washington Post seemed to miss or perhaps failed to appreciate when relying on its sources and then sharing those findings with a public largely unversed in the nuances of Jan. 6 and its related investigations.

In the same way that Belew suggests sedition trials and convictions can act as an important deterrent to possible criminal extremists, it would seem just as vital that non-criminal, non-seditious Americans accurately grasp these serious proceedings, too. Being empowered with the ability to cut through the bullshit being spun by the far right, or Jan. 6 conspiracy theorists, hinges considerably on having a clear understanding, or at least a thorough consideration, of the historical evidence at the trials themselves.

For my purposes, perhaps most striking in that Post piece was a detail that later needed to be corrected. In the first iteration of its story, the Post incorrectly stated that the Justice Department attempted to prosecute those involved in the kidnapping plot of Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer with the sedition statute.

But they did not use it in that case; so the comparison wasn’t just incorrect but it wasn’t apt at its inception. What would be more apt would be to mention how prosecutors used it in the Hutaree Christian militia case from 2010. This is a critical distinction because the Hutaree case is deeply relevant as Oath Keepers appeals are underway. With the Hutaree militia, the judge acquitted the defendants of seditious conspiracy after the government closed its case. U.S. District Judge Victoria Roberts felt prosecutors had failed to sufficiently prove the militia members intended to forcibly resist the U.S. government. It was a just lot of vile talk, she found, but it didn’t rise to seditious conspiracy.

I will broach more about this later in this piece but first, let’s return to some baseline details on the appeals in progress.

OATH KEEPERS ON APPEAL

At his sentencing in May, Rhodes puffed up his chest to deliver a self-aggrandizing diatribe extremely short on remorse and extraordinarily heavy on claims of political persecution by the U.S. government and the “weaponization” of free speech by the Justice Department. His attorneys said early into the trial that if they lost, an appeal would certainly follow.

And it has.

Rhodes’ lawyers, James Lee Bright and Phillip Linder, did not return a request for comment to emptywheel this week but for the moment, according to the docket at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, Rhodes and almost all of his co-defendants from the first trial group including Kelly Meggs, Kenneth Harrelson, and Jessica Watkins, have consolidated their efforts to attempt an appeal.

Another batch of Oath Keepers tried, charged, and convicted of seditious conspiracy include Roberto Minuta, David Moerschel, Edward Vallejo, and Joseph Hackett. They were split off into a second trial group for logistical reasons.

The only Oath Keepers convicted of seditious conspiracy as of Thursday who have yet to officially indicate whether they will appeal are Ed Vallejo and Joseph Hackett.

Vallejo’s attorney, Matthew Peed, wrote in an email to emptywheel this week that he felt it was “likely” his client would appeal. Hackett’s lawyer, Angie Halim, did not return multiple requests for comment. (Key to note: An appeal cannot be formally entered until a defendant’s final judgment makes it onto the docket and neither Vallejo nor Hackett’s final judgment has appeared yet.)

Rhodes’ attorney Phil Linder told CBS recently he expects it will take months to craft an appeal and one can only assume the same would apply to Kelly Meggs’ attorney Stanley Woodward given the demands on his schedule of late. Woodward also represents Waltine Nauta, former President Donald Trump’s valet and alleged co-conspirator in the Mar-a-Lago classified documents case. Woodward also represents Ryan Samsel, a Jan. 6 defendant who figures prominently in most “fedsurrection” conspiracy theories and he represents Frederico “Freddie” Klein, a former Trump-era State Department official. Klein faces a number of charges including assaulting police on Jan. 6, and he goes to trial in October. Woodward will also represent Trump’s former trade adviser Peter Navarro once Navarro’s trial for criminal contempt gets underway in September. Navarro, prosecutors say, defied a subpoena issued to him by the House Select Committee to Investigate the Jan. 6 Attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Over the next 30 days, the Oath Keepers will continue to get their houses in order. Rhodes’ lawyers, according to a recent letter from the court clerk, have not yet been admitted to practice before the appeals court in but they have until July 12 to get admitted.

THE DEVIL IN THE DETAILS

After the massive unraveling of evidence and testimony at trial, it is hard to imagine a scenario in which an appeal, especially one from Rhodes, will contain, well, anything particularly novel. But the far more important factor will be whether his appeal will convince an appellate judge that his speech was not seditious.

Another one of his attorneys, Ed Tarpley, said after Rhodes was sentenced to 18 years in prison that the former far-right leader wouldn’t stop speaking up because it was a matter of principle.

The Justice Department had “weaponized” the First Amendment and used Rhodes’ own words against him to secure a conviction, Tarpley said.

Rhodes’ words were “used against him” technically speaking. But it wasn’t just his words that helped get him convicted though jurors did see mind-boggling amounts of evidence featuring his communications.

They heard speeches and reviewed texts and phone calls as well as a recorded meeting where he called for revolution days after the 2020 election. He decried the election as unconstitutional and fraudulent and promoted disinformation to rile up his group or to entice them to act in concert with him. He directed Kelly Meggs, a Florida division leader, to coordinate operations in advance of the 6th and on the 6th. He oversaw the coordination of the gigantic weapons stash, or a quick reaction force (QRF) with the help of his co-defendants. The cache was set up at a hotel in Virginia, just over the Potomac River from the Capitol. Aware of the gun laws in D.C., Oath Keepers, from points all over the U.S., understood and received directions to drop their weapons at the QRF. Rhodes’ future co-defendant Ed Vallejo would stand by awaiting Rhodes’ orders to haul the weapons in if asked.

The beginnings of Rhodes’ intent were aired out in trial courtesy of a recorded GoTo Meeting with fellow Oath Keepers on Nov. 9, 2020.. Rhodes didn’t mince words and in fact, his fury was so complete, he scared one Oath Keeper into eventually reporting the call to the authorities.

They would have to fight to keep Trump in office and this wasn’t a metaphorical “fight.”

“Let’s make no illusion about what’s going on in this country. We’re very much in exactly the same spot that the founding fathers were in like March 1775. Now—and Patrick Henry was right. Nothing left but to fight. And that’s true for us too. We’re not getting out of this without a fight. There’s going to be a fight. But let’s just do it smart and let’s do it while President Trump is still Commander in Chief and let’s try to get him to do his duty and step up and do it,” Rhodes said.

Trump would not urge his supporters to descend on D.C. until Dec. 19, but prosecutors demonstrated that the Oath Keepers’ seditious conspiracy didn’t simply or only start to exist once Trump called for the “wild” event.

During that Nov. 9 call, Rhodes’ told members they would need to be willing to travel to Washington and prepare to war with “antifa.” This was something he explained had multiple benefits.

If they were there to stop “antifa” from attacking Trump supporters, it would give Trump a reason to invoke the Insurrection Act and raise Oath Keepers to his side.

“I’m willing to sacrifice myself for that. Let’s start the fight there, OK? That would give President Trump what he needs frankly,” Rhodes said.

Getting Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act so the “fraudulent” election could be stopped was ideal for Rhodes and as the weeks after the election passed and Trump lost lawsuit after lawsuit challenging the results, his desperation grew.

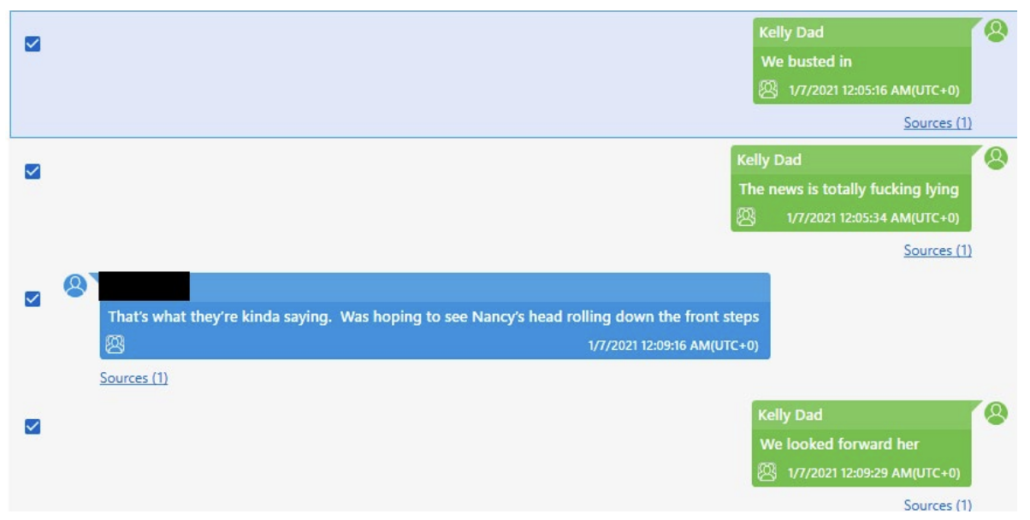

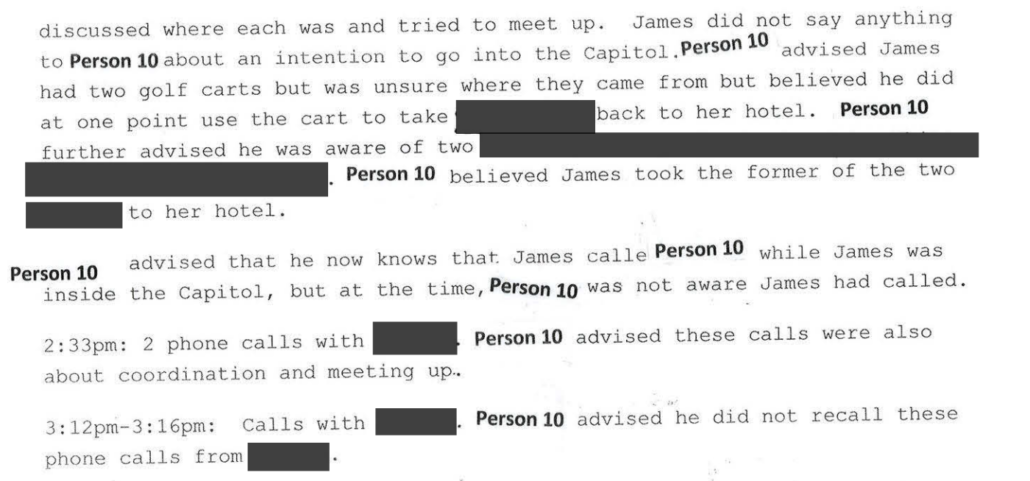

On Jan. 6, Rhodes never stepped foot inside the Capitol. He stalked its grounds as he communicated with Oath Keepers on site and just moments before Oath Keepers breached, cell phone data showed Rhodes had called Meggs in what prosecutors argued was an order to get inside the Capitol and plow ahead. Prosecutors said the defendants understood, even without it being said explicitly, that this was a means to stop Congress from doing its duty. At trial, footage after this call in question appears to show Meggs entering the Capitol as if on cue.

Rhodes wasn’t indicted for propagandizing. He wasn’t indicted for having an opinion contrary to fact. He wasn’t indicted for wanting Trump to be in office even after Trump lost the election and then lost dozens of lawsuits seeking to overturn the results.

Rhodes wasn’t indicted for writing public letters and posting them online urging Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act in order to stop the “fraudulent” election of Joe Biden, a man Rhodes proclaimed was a “puppet” for communist China. (For the record, Rhodes wrote two of these letters; one was published on Dec. 14 and another on Dec. 23, 2021.)

And Rhodes certainly wasn’t indicted for merely traveling from Texas to D.C. on Jan. 6 to attend a rally with thousands of other people who showed up to support Trump’s Big Lie.

Rhodes was charged and convicted of seditious conspiracy, obstructing an official proceeding, and tampering with evidence because his words, when coupled with his conduct and the conduct of the men he oversaw, far exceeded the protections the First Amendment has to offer.

Rhodes didn’t simply oversee a bunch of loudmouth oafs hand-painting protest signs in a hotel in Virginia before sauntering over to the Capitol to chant outside of it peacefully.

When he was en route to D.C. from Texas, bank statements and receipts showed. Rhodes spent more than $10,000 on firearms and gear like sights, scopes, ammunition, and night vision equipment. On their return to Texas after the 6th, Rhodes didn’t stop spending. In fact, he spent at least another $30,000 on weapons and equipment. Jurors saw maps and cell extraction reports that showed how, when, and where Rhodes coordinated these purchases and communications. Jurors saw how Rhodes coordinated with Oath Keeper Joshua James while returning to Texas and how they worked together to collect firearms and tactical gear. And all the while, Rhodes angled to conceal his movements, using his then-girlfriend Kellye SoRelle as a cutout to communicate with Oath Keepers via text through her and her phone. It was revealed to jurors also that James, who pleaded guilty to seditious conspiracy, sent a message to Rhodes as late as Inauguration Day saying, “After this… if nothing happens, it’s Civil War 2.0.”

When former Oath Keeper Terry Cummings, who traveled with other members to D.C. for the 6th, testified against Rhodes in court, he said not since his time in the military had he ever seen so many guns in one place.

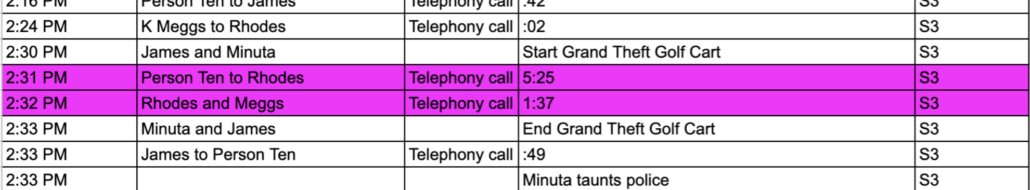

Rhodes’ defense hinged on the argument that Oath Keepers came to Washington merely to serve as a security force for Trump VIPs attending speeches or rallies. One of those VIPs was ratfucker Roger Stone. Oath Keepers Joshua James and Roberto Minuta were tasked to guard him. Yet they would leave Stone at the hotel and speed towards the Capitol on golf carts as soon as Rhodes called them to his side. Meanwhile, Stone hightailed it out of D.C.

At other times, the defense claimed Oath Keepers came to Washington to provide medical support as needed. Defendant and former Army medic Jessica Watkins had medical training, that was true, but her defense was undercut by her own admission on the witness stand: She did impede police when she forced her way into the Capitol and pushed past them.

At sentencing, she wept when she recalled memories of the police officer who was overrun thanks to her conduct.

It seemed at trial the defense’s goalposts shifted depending on which defendant was under questioning or how a witness performed. The disclosed purpose for amassing the weapons cache or going to the Capitol regularly shifted around its edges in the Rhodes trial, and so many stories simply didn’t hold up under the scrutiny of cross-examination or redirect.

Memorably, assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Nestler remarked to jurors during closing arguments in the first Oath Keepers trial that for all the claims of Oath Keepers being an organized security force on Jan. 6, not one defendant was licensed or insured to provide security services and no one held any contracts for these supposed clients.

And if the evidence from before Jan. 6 or the day of didn’t sink him, what followed proved Rhodes wanted to overthrow a government where Joe Biden was its executive. On Jan. 10, 2021, while downtown D.C. was still bustling with National Guard left over to protect the Capitol and nearby federal buildings, Rhodes took a meeting in a parking lot in Texas with U.S. veteran Jason Alpers.

Alpers testified that he had “indirect” ties to the Trump White House but no further description was offered in court. Alpers said he linked up with Rhodes through an associate of Allied Security Operations Group, the same group that led an “audit” of voting machines in Antrim County, Michigan. (Michigan, of course, was one of several battleground states where Trump’s lawyers, including Sidney Powell and others, claimed fraud was pervasive. Powell was sanctioned for her role in pursuing such baseless claims in the courts last week.)

The meeting was set so Rhodes could pass a message to Trump. Alpers would secretly record the exchange. Rhodes was furious. He wouldn’t condemn the violence on the 6th but he had other regrets.

If Trump was going to just let himself be removed illegally, Rhodes remarked, “then we should have brought rifles.”

“We could have fixed it right then and there,” he said on the recording before adding that he would “hang fucking [then Speaker of the House Nancy] Pelosi from the lamppost.”

Furious, he tapped out a message into Alpers’ phone because he expected Alpers would pass it along to his Trump contact.

Trump would be killed by his enemies if he didn’t act now, Rhodes warned.

‘You must use the Insurrection Act… if you don’t, you and your family will be imprisoned or killed. You and your children will die in prison… you must do as Lincoln did. He arrested congressmen, state legislators and issued a warrant for SCOTUS Chief Justice Taney. Take command like Washington would… Go down in history as a savior of the Republic, not the man who surrendered it… I’m here for you and so are all of my men. We will come help if you need us,” Rhodes wrote.

He claimed he had 40,000 Oath Keepers backing him and millions of others who felt as they did.

He added: “There’s gonna be combat here on U.S. soil no matter what” and warned that the Biden administration would “disarm us all,” if allowed to take office.

The message was too extreme for Alpers to pass along. It didn’t help, the veteran testified, that Rhodes’ then-lover Kellye SoRelle, who was also there, was drunk. It put Alpers off. It was all too unprofessional and his confidence was shaken. On cross-examination, Alpers said he delayed reporting the meeting to the FBI because he didn’t want to get involved any further.

All of these elements are just slivers of what jurors heard in the weeks-long trial.

There were also several intense days where emotions ran high, including those where the parties started to dig into claims that Oath Keepers went to help Capitol Police after getting inside.

Meggs, Harrelson, and Watkins attorneys insisted their clients “assisted” U.S. Capitol Police Officer Harry Dunn who was stationed outside then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office. Armed with a rifle, Dunn told jurors he knew it wouldn’t take much for someone to grab it off him and make a bad situation worse. He told Oath Keepers to leave, he told them they were hurting police; he told them police were “getting the shit kicked out of them.”

The Oath Keepers wouldn’t leave right away though, they hung around him a bit longer instead. When prosecutors asked Dunn on redirect at trial what would have helped him that day, the officer was succinct: if they left, or never come in, that would help.

So, to review, here are the convictions from the Oath Keepers sedition cases. (It is worth noting that if Rhodes manages to pull off an appeal, he could also be resentenced.)

On seditious conspiracy:

- Elmer Stewart Rhodes, Kelly Meggs, Roberto Minuta, David Moerschel, Joseph Hackett

On conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding:

- Kelly Meggs, Jessica Watkins, Roberto Minuta, David Moerschell, Edward Vallejo, Joseph Hackett

On obstruction of an official proceeding:

- Elmer Stewart Rhodes, Kelly Meggs, Jessica Watkins, Kenneth Harrelson, Thomas Caldwell, Roberto Minuta, David Moerschel, Edward Vallejo

On conspiracy to prevent officials from discharging their duties:

- Kelly Meggs, Jessica Watkins, Kenneth Harrelson, David Moerschel, Edward Vallejo, Joseph Hackett

On tampering or destruction of evidence:

- Elmer Stewart Rhodes, Kelly Meggs, Kenneth Harrelson, Thomas Caldwell, Roberto Minuta, Joseph Hackett

Impeding officers during a civil disorder:

- Jessica Watkins

IS EVERYTHING OLD NEW AGAIN?

When the federal judge presiding over the Hutaree matter tossed all of the sedition charges against those defendants, she explained that prosecutors had failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the Christian militia members took concrete steps to violently revolt against the federal government with the aid of weapons of mass destruction.

The Hutarees were recorded discussing how police were their enemies and how they wanted to kill them. They discussed how a war against the U.S. government was necessary, too. But Judge Victoria Brown ruled that a conspiracy required a specific plot or a knowing agreement to break the law or a knowing intent to join that effort. Guilt by association was not enough, she said, and neither was repugnant conversation.

A Hutaree defense attorney noted in an interview with The Guardian last October when the Oath Keepers went on trial, that when it came to the Hutaree militia, beyond a lack of a plan, there was also “no action taken.” Hutarees may have shared disdain for law enforcement, communications showed, but, he argued, it pretty much stopped there.

After the sedition acquittals for the Hutarees in 2012, a law professor from Wayne State University noted to the New York Times that the outcome just went to show how difficult it is to prosecute cases involving groups engaged in political speech. The professor also noted how Hutarees were “a fairly disorganized group” who may have “talked big” but didn’t seem to be doing much otherwise.

At the Oath Keepers trial, the defense was insistent that because there was not a concrete plan laying out the Oath Keepers’ precise efforts up to, on, or after Jan. 6, the government’s case was overcharged and amounted to a gross infringement on their First Amendment rights.

But neither Judge Mehta nor the jury believed that was the case for the Oath Keepers who were ultimately convicted of seditious conspiracy. At Rhodes’ sentencing, Judge Mehta was unequivocal on this point, telling Rhodes he posed an “ongoing peril to democracy.”

He was the one giving orders, Mehta said.

“He was the one organizing teams that day. He was the reason they were, in fact, in Washington, D.C. Oath Keepers wouldn’t have been there but for Stewart Rhodes, I don’t think anyone contends otherwise. He was the one who gave the order to go, and they went,” he said.

When the jury was instructed before deliberations, they were told that a conspiracy was defined as two or more people trying to accomplish some unlawful purpose and in order to sustain a seditious conspiracy charge, they must agree that a defendant conspired with at least one other person to oppose the government by force to delay and impede it; or they reached an agreement to use force in the ordinary sense of the word; or simply that they contemplated using force while at least one defendant actually used it.

The government had no burden, Mehta said, to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that there was an express agreement or an implied one. They just had to prove that the members of the conspiracy met, talked about unlawful objectives, and agreed to some of the details or what the means were by which objectives could be accomplished. The success of that aim was irrelevant.

Jurors deliberated for three days in the Rhodes trial; jurors in the second trial group took just over a week to reach a verdict. The end results were a mixed bag of verdicts, suggesting that jurors meticulously reviewed each defendant’s conduct.

Watkins was acquitted of sedition but convicted of conspiracy to obstruct a proceeding, obstructing an official proceeding, conspiracy to prevent officials from discharging their duties, and impeding officers during a civil disorder. She recruited Oath Keepers and coordinated with them to breach the building and disrupt police on Jan. 6, but the jury, in the end, wasn’t fully convinced her role was central to that of a seditious conspiracist.

The bar to convict remained high even for someone who recorded themselves breaching the building while actively and repeatedly encouraging others to “push, push, push” because the police “can’t hold us.” Before sentencing her to 8.5 years, Judge Mehta remarked that no one would suggest she is Rhodes or even Kelly Meggs.

“But your role in those events is more than that of a foot soldier. I think you can appreciate that,” he said.

Will these words haunt an appeal to come?

When sentencing Rhodes and Meggs, Judge Mehta was far harder on them than their co-defendants also convicted of seditious conspiracy. He handed down an 18-year sentence to Rhodes and 12 years to Meggs with terrorism enhancements applied. The maximum on seditious conspiracy alone is 20 years. Minuta was sentenced to just 4.5 years; Joseph Hackett to 3.5 years. Vallejo and Moerschel received just 3 years. And again, that would include all of the convictions weighed in.

Mehta emphasized to Rhodes at his sentencing that there was no question he “took up arms and fomented a revolution” on Jan. 6.

“That’s what you did. Those aren’t my words. Those are yours,” Mehta said. “You are not a political prisoner, Mr. Rhodes. You are not here for your beliefs.”

Perhaps this encapsulates the very reason why it matters that the sedition charge was used instead of abandoned early on. The evidence would indicate this wasn’t merely a First Amendment matter. Perhaps it may have been easier for Rhodes or Meggs or other Oath Keepers charged and convicted of seditious conspiracy to wriggle out of an obstruction charge if the focus on sedition wasn’t also on the table to start.

But whatever the case may be, that’s the recent past. And while important, there’s now an equally if not more important future to ponder just ahead.

At a time when the U.S. is awash in far-right extremism; when the man who incited the insurrection on Jan. 6 is now twice-indicted yet still running for president and running on a vengeance platform; at a time when he and other right-wing politicians vow to pardon all Jan. 6 defendants if ever given power by the body politic to do it—it will matter what happens with these appeals.

Will the Oath Keepers convicted of sedition appeal their sentences? Or will they appeal the conviction? Appealing the conviction would seem the likely route given Mehta’s light touch at sentencing for most. And as part of his tough-guy-patriot-against-the-Deep-State-routine, Rhodes has already said he’s willing to do prison time for his beliefs. An appeal on the conviction that could potentially humiliate the U.S. government would seem too tantalizing for a man like Stewart Rhodes to pass up.

If terabytes of evidence weren’t enough, if hours and hours of video footage weren’t enough, if proclamations and concerted efforts to foment an armed rebellion live on television aren’t enough to maintain the Oath Keepers seditious conspiracy convictions, then one must wonder, what will happen if history repeats itself?