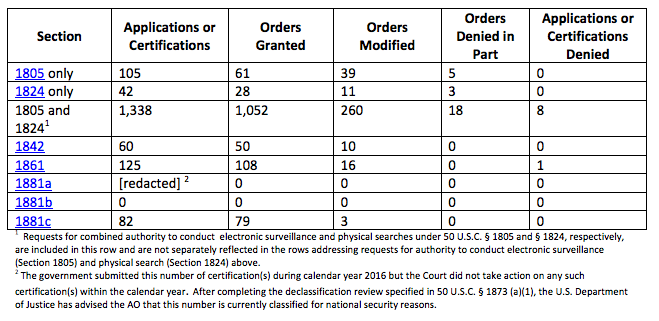

As I mentioned in this post on FISA and the space-time continuum, I’m going to be focusing closely on the FISA implications of Keith Gartenlaub’s child porn prosecution.

Gartenlaub was a Boeing engineer in 2013 when the FBI started investigating him for sharing information with China (see this and this story for background). He was suspected, in significant part, because of relationships and communications tied to his wife, who is a naturalized Chinese-American and whose family appears well-connected in China. The case is interesting for the way the government used both FISA and criminal searches to prosecute him for a non-national security related crime.

The case is currently being appealed to the 9th Circuit; it will be heard on December 4. His defense is challenging several things about his conviction, including that there was insufficient evidence to deem him an Agent of a Foreign Power (and therefore to obtain the ability to conduct a broader search than might be permitted under a criminal warrant), as well as that there was insufficient evidence offered at trial that he knowingly possessed the 9-year old child porn on which his conviction rests. I think there’s some merit to the latter claim, but I’m going to bracket it for my discussion, both because I think the FISA issues would remain important even if the government’s case on the child porn charge were far stronger than it is, and because I think the government may be sitting on potentially inculpatory evidence.

In this post, I’m going to show that it is almost certain that the government changed FISA minimization procedures to facilitate using FISA to prosecute him for child porn.

Timeline

The public timeline around the case looks like this (and as I said, I believe the government is hiding some bits):

Around January 28, 2013: Agent Wesley Harris reads article that leads him to start searching for Chinese spies at Boeing

February 7, 8, and 22, 2013: Harris interviews Gartenlaub

June 18, 2013: Agent Harris obtains search warrant for Gartenlaub and his wife, Tess Yi’s, Google and Yahoo accounts

Unknown date: Harris obtains a FISA order

January 29, 2014: Using FISA physical search order, FBI searches Gartenlaub’s home, images three hard drives

June 3, 2014: Harris sends files to National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which confirms some files display known victims

August 22, 2014: Criminal search warrant obtained for Gartenlaub’s premises

August 27, 2014: FBI searches Gartenlaub’s properties, seizing computers used as evidence in trial, arrests him

August 29, 2014: Government reportedly says it will dismiss charges if Gartenlaub will cooperate on spying

October 23, 2014: Grand jury indicts

December 10, 2015: Guilty verdict

FBI used a criminal search warrant to obtain evidence, then obtained a FISA order

As you can see from the timeline, the government first obtained a criminal search warrant for access to Gartenlaub and his wife’s email accounts (Gartenlaub also got an 1806 notice, meaning they used a FISA wiretap on him at some point). Only after that did they execute a FISA physical search order to search his house and image his computers. Which means — unless they had a FISA order and a criminal warrant simultaneously — they had already convinced a judge it was likely Gartenlaub’s emails would provide evidence he was “remov[ing ] information, including export controlled technical data, from Boeing’s computer networks to China.” In his affidavit, Agent Harris cited violations of the Arms Export Control Act and Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

Then, after probably months of reviewing emails later, having already shown probable cause that could have enabled them to get a search warrant to search Gartenlaub’s computer for those specific crimes — that is, proof that he had exploited his network access at Boeing in order to obtain data he could share with his wife’s Chinese associates — the government then went to FISA and convinced a judge they had probable cause Gartenlaub (or perhaps his wife) was acting as an agent of a foreign power for what are assumed to be the same underlying activities.

The government insists it still had adequate evidence Gartenlaub or his wife was an agent of a foreign power under FISA

The government’s response to Gartenlaub’s appeal predictably redacts much of the discussion to support its claim that it had sufficient probable cause, after months of reading his emails, to claim he or his wife was an agent of China. But the structure of it — with an unredacted paragraph addressing weaknesses with the criminal affidavit, followed by a redacted passage of unknown length, as well as a redacted footnote modifying the idea that the criminal affidavit “merely ‘recycled’ details that were found in the Harris affidavit” (see page 38-39) — suggests they raised evidence beyond what got included in the criminal affidavit. That’s surely true; it presumably explains what was so interesting about Yi’s family and associates in China as to sustain suspicion that they would be soliciting Boeing technology.

In any case, in a filing in which the government admits that “the [District] court expressed ‘some personal questions regarding the propriety of the FISA court proceeding even though that certainly seems to be legally authorized’,” the government pushed the Ninth Circuit to adopt a deferential standard on probable cause for FISA orders, in which only clear error can overturn the probable cause standard.

The Court has not previously articulated the standard of review applicable to an underlying finding of probable cause in a FISA case. In the analogous context of search warrants, this Court gives “great deference” to an issuing magistrate judge’s findings of probable cause, reviewing such findings only for “clear error.” Krupa, 658 F.3d at 1177; United States v. Hill, 459 F.3d 966, 970 (9th Cir. 2006) (same); United States v. Clark, 31 F.3d 831, 834 (9th Cir. 1994) (same). “In borderline cases, preference will be accorded to warrants and to the decision of the magistrate issuing it.” United States v. Terry, 911 F.2d 272, 275 (9th Cir. 1990). The same standard applies to this Court’s review of the findings in Title III wiretap applications. United States v. Brown, 761 F.2d 1272, 1275 (9th Cir. 2002).

Consistent with these standards and with FISA itself, the Second and Fifth Circuits have held that the “established standard of judicial review applicable to FISA warrants is deferential,” particularly given that “FISA warrant applications are subject to ‘minimal scrutiny by the courts,’ both upon initial presentation and subsequent challenge.” United States v. Abu-Jihaad, 630 F.3d 102, 130 (2d Cir. 2010); accord United States v. El-Mezain, 664 F.3d 467, 567 (5th Cir. 2011) (noting that representations and certifications in FISA application should be “presumed valid”). Other courts, reviewing district court orders de novo, have not discussed what deference applies to the FISC. See, e.g., Demeisi, 424 F.3d at 578; Squillacote, 221 F.3d at 553-54.

The government submits that the appropriate standard should be deferential. Consistent with findings of probable cause in other cases, the Court should review only for “clear error,” giving “great deference” to the initial conclusion that a FISA application established probable cause.

And, of course, the government argues that even if it didn’t meet the standards required under FISA, it still operated in good faith.

By using a FISA rather than a criminal search warrant, the FBI had more leeway to search for unrelated items

Nevertheless, having read Gartenlaub’s email for months and presumably having had the opportunity to obtain a warrant to search his computers for those specific crimes, the government instead obtained a FISA order that allowed the FBI to search his devices far more broadly, opening up decades old files named with sexually explicit names in the guise of finding intelligence on stealing Boeing’s secrets. Here’s how Gartenlaub’s lawyers describe the search in his appeal, a description the government largely endorses in their response:

The FISC can only authorize the government to search for and seize “foreign intelligence information.” 50 U.S.C. §§ 1822(b), 1823(a)(6)(A), 1824(a)(4). The order authorizing the January 2014 search of Gartenlaub’s home and computers presumably complied with this restriction. “Foreign intelligence information” (defined at 50 U.S.C. §§ 1801(e) and 1821(1)) does not include child pornography. Nonetheless, as detailed in the government’s application for the August 2014 search warrant, the agents imaged Gartenlaub’s computers in their entirety, reviewed every file, and–upon discovering that some of the files contained possible child pornography–subjected those and related files to detailed scrutiny, including sending them to the National Center for Exploited Children for analysis. ER248-56, 262-68. In an effort to establish that Gartenlaub had downloaded the child pornography, the agents also examined and analyzed a number of other files on the computers, none of which had anything to do with “foreign intelligence information.” ER255-62, 268-70.

As far as the record shows, the agents conducted this detailed, far-ranging analysis without obtaining any court authorization beyond the initial FISC order. In other words, after encountering suspected child pornography files, the agents did not stop their search and seek a warrant authorizing them to open and review those files and other potentially related files. Instead, they opened, examined, and analyzed the suspected child pornography files and a number of other files having nothing to do with foreign intelligence information. They then incorporated the results of that analysis into the August 2014 search warrant application. ER248- 49. That application, in turn, produced the warrant that gave the agents authority to search for and seize the very materials that they had already seized and searched under the purported authority of the January 2014 FISC order.

How did agents authorized to search for “foreign intelligence information” end up opening, examining, and analyzing suspected child pornography files and a number of other files that had nothing to do with the only authorized object of the search? The agents apparently relied on the following argument: To determine whether Gartenlaub’s computers contained foreign intelligence information, it was necessary to open and review every file; after all, a foreign spy might cleverly conceal such information in .jpg files with sex-themed names or in other non-obvious locations. And after opening the files, the child pornography and other information was in “plain view” and thus could be lawfully seized under the Fourth Amendment.

As a result of these broad standards, and of Gartenlaub’s habit of retaining disk drives from computers he no longer owned, the FBI found files dating back to 2005, from a computer Gartenlaub no longer owned.

Upon finding that those files included apparent child porn, the FBI sent them off to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which confirmed some of the images included known victims. Almost two months later, FBI conducted further (criminal) searches, and arrested Gartenlaub for child porn.

In December 2015, Gartenlaub was found guilty on two counts of child porn, though one count was vacated by the judge after the verdict.

FBI changed standard minimization procedures to permit sharing with NCMEC

The timeline above is what would have been available to Gartenlaub’s defense team.

But in 2015 and 2017, two new details were added to the timeline.

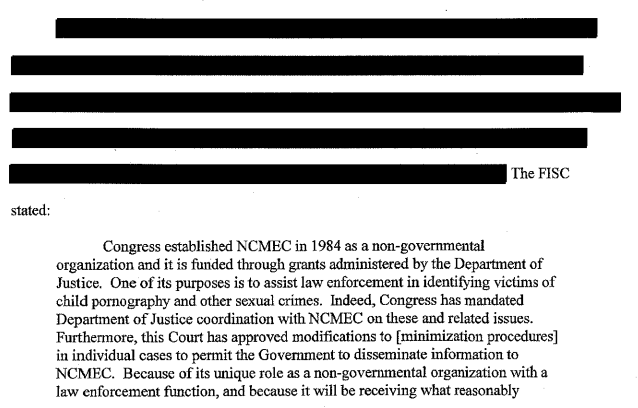

First, on April 11, 2017, two months after Gartenlaub submitted his opening brief in the appeal on February 8, the government released an August 11, 2014 opinion approving the sharing of FISA-obtained data with NCMEC.

Congress established NCMEC in 1984 as a non-governmental organization and it is funded through grants administered by the Department of Justice. One of its purposes is to assist law enforcement in identifying victims of child pornography and other sexual crimes. Indeed, Congress has mandated Department of Justice coordination with NCMEC on these and related issues. See Mot. at 5-8. Furthermore, this Court has approved modifications to these SMPs in individual cases to permit the Government to disseminate information to NCMEC. See Docket Nos. [redacted]. Because of its unique role as a non-governmental organization with a law enforcement function, and because it will be receiving what reasonably appears to be evidence of specific types of crimes for law enforcement purposes, the Government’s amendment to the SMPs comply with FISA under Section 180l(h)(3).1

As noted, in the past the FISC had approved sharing FISA-collected data with NCMEC on a case-by-case basis. But in 2014, in the weeks while it prepared to arrest Gartenlaub on child porn charges tied to a search that only found the child porn because it used the broader FISA search standard, the government finally made NCMEC sharing part of the standard minimization procedures.

Even on top of this coincidental timing, there are reasons to suspect DOJ codified the NCMEC sharing because of Gartenlaub’s case. For example, in the government’s response there’s a passage that clearly addresses how NCMEC got involved in the case that bridges the discussion of use of child porn evidence discovered in plain view in the criminal context and the discussion of its use here.

Non-FISA precedents also foreclose defendant’s claims. Analyzing a Rule 41 search warrant, this Court has held that using child pornography inadvertently discovered during a lawful search is consistent with the Fourth Amendment. Giberson, 527 F.3d at 889-90 (ruling that “the pornographic material [the agent] inadvertently discovered while searching for the documents enumerated in the warrant [related to document identification fraud] was properly used as a basis for the third warrant authorizing the search for child pornography”);

[additional precedents excluded]

[CLASSIFIED INFORMATION REMOVED] With the benefit of NCMEC’s assistance, the government then sought and obtained the August 2014 search warrants, authorizing the search of defendant’s residence and storage units for child pornography. (CR 73; GER 901-53). The fruits of this warrant were then used in defendant’s prosecution. The use of information discovered during the prior lawful January 2014 search in the subsequent search warrant application was proper. Giberson, 527 F.3d at 890.

The redacted discussion must include not only a description of how NCMEC was permitted to get involved, but in the approval approving this as part of the minimization procedures, which (after all) are designed to protect Americans under the Fourth Amendment.

Of particular interest, the government argued that one of the precedents Gartenlaub cited was not binding generally, and especially not binding on the FISC.

The concurring opinion in CDT, upon which defendant relies, does not aid him. That concurrence is not “binding circuit precedent” or a “constitutional requirement,” much less one binding on the FISC. Schesso, 730 F.3d at 1049 (the “search protocol” set forth in the CDT concurrence is not “binding circuit precedent,” not a[] constitutional requirement[],” and provides “no clear-cut rule”); see CDT, 621 F.3d at 1178 (observing that “[d]istrict and magistrate judges must exercise their independent judgment in every case”); Nessland, 601 Fed. Appx. at 576 (holding that “no special protocol was required” for a computer search). Defendant thus cannot demonstrate any error relating to any FISC-authorized search.

The FISC had, by the time of the search relying on the FISA-obtained child porn as evidence, already approved the use of child porn obtained in a FISA search. So the government could say the CDT case was not binding precedent, because it already had a precedent in hand from the FISC. Of course, it didn’t tell Gartenlaub that.

Of course, that’s not proof that the government codified the NCMEC sharing just for the Gartenlaub case. But there’s a lot of circumstantial evidence that that’s what happened.

The government still has not formally noticed this change to Gartenlaub

As I noted above, the government released the FISC order approving the change in the standard minimization procedures too late to be of use for Gartenlaub’s opening brief. That’s a point EFF and ACLU made in their worthwhile amicus submitted in the appeal.

For example, in this case, the government apparently refused to disclose the relevant FBI minimization procedures to Gartenlaub’s counsel even though other versions of those minimization procedures are publicly available. See Standard Minimization Procedures for FBI Electronic Surveillance and Physical Search Conducted Under FISA (2008). 8

We can debate whether the standard approval for NCMEC sharing is a good thing or whether it invites abuse, offering the FBI an opportunity to use more expansive searches to “find” evidence of child porn that it can then use as leverage in a foreign intelligence context (which I’ll return to). I suspect it is wiser to approve such sharing on a case-by-case basis, as had been the case before Gartenlaub.

But from this point forward, I would assume the FBI will routinely use this provision as an excuse to conduct particularly thorough searches for child porn, on the logic that obtaining any would provide great leverage against an intelligence target.

The timing of the approval of NCMEC sharing under Section 702

I have said repeatedly, I think the government is withholding some details.

One reason I think that is because of another remarkable coincidence of timing.

As I first reported here, the first notice that the government had approved the sharing with NCMEC in standard minimization procedures came in September 2015, when the government released the 2014 Thomas Hogan Section 702 opinion that approved such sharing under Section 702. The opinion relied on the earlier approval (by Rosemary Collyer), but redacted all reference to the timing and context of it, as well as a footnote relating to it.

I find the timing of both the release and the opinion itself to be of immense interest.

First, the government had no problem releasing this opinion back in 2015, while Gartenlaub was still awaiting trial (though it waited until almost two months after the District judge in his case, Christina Snyder, rejected his FISA challenge on August 6, 2015). So it was fine revealing to potential intelligence targets that it had standardized the approval of using FISA information to pursue child porn cases, just not revealing the dates that might have made it useful for Gartenlaub.

I’m even more interested in the timing of the order: August 26. The day before the FBI got its complaint approved and arrested Gartenlaub.

The FBI had long ago submitted FISA information to NCMEC. But it waited until both the standard minimization procedures for traditional FISA and for Section 702 had approved the sharing of data with NCMEC before they arrested Gartenlaub.

That’s one of several pieces of data that suggests they may have used Section 702 against Gartenlaub, on top of the other mix of criminal and FISA authorizations.

To be continued.

Updated timeline

Around January 28, 2013: Agent Wesley Harris reads article that leads him to start searching for Chinese spies at Boeing

February 7, 8, and 22, 2013: Harris interviews Gartenlaub

June 18, 2013: Agent Harris obtains search warrant for Gartenlaub and his wife, Tess Yi’s, Google and Yahoo accounts

Unknown date: Harris obtains a FISA order

January 29, 2014: FBI searches Gartenlaub’s home, images three hard drives

June 3, 2014: Harris sends files to National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which confirms some files display known victims

August 11, 2014: Rosemary Collyer approves NCMEC sharing for traditional FISA standard minimization procedures

August 22, 2014: Search warrant obtained for Gartenlaub’s premises

August 26, 2014: Thomas Hogan approves NCMEC sharing for FISA 702

August 27, 2014: FBI searches Gartenlaub’s properties, seizing computers used as evidence in trial, arrests him

August 29, 2014: Government reportedly says it will dismiss charges if Gartenlaub will cooperate on spying

October 23, 2014: Grand jury indicts

August 6, 2015: Christina Snyder rejects Gartenlaub FISA challenge

September 29, 2015: ODNI releases 702 NCMEC sharing opinion

December 10, 2015: Guilty verdict

February 8, 2017: Gartenlaub submits opening brief

April 11, 2017: Government releases traditional FISA NCMEC sharing opinion

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)